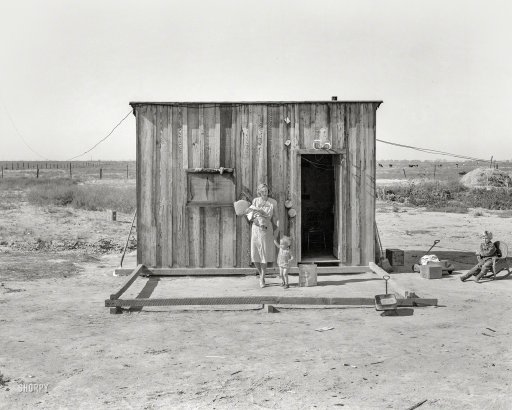

Dorothea Lange Home of rural rehabilitation client, Tulare County, CA 1938

Our by now regular contributor Dr. Nelson Lebo III, the New Englander ‘lost’ in New Zealand, sent me another article, and it’s great (well, in my view). His title for the article may put some people on the wrong foot, but I think that’s alright.

I’ve been to New Zealand a few times, and Nicole of course has even moved there, so I was aware of how poorly constructed many homes are -and often made of wood-, but I’d never heard of ‘curtain banks’. Still, they exist all over the country. Turns out, lots of New Zealand homes are so damp and moldy that curtains can literally save lives, and certainly make them more comfortable/bearable. But many people are too poor to be able to afford curtains. Hence the curtain banks. I’d be curious to know if similar initiatives exist anywhere lese on the planet. Do let me know.

Nelson’s second ‘bank’ is made of/filled with water. Agriculture, in particular the one-trick pony of the dairy industry, has caused the land to deteriorate so badly that water washes off the hillsides and the land without natural barriers like trees and shrubs left to stop and naturally regulate it. In other words, there is no ‘water bank’ or ‘stream bank’ left. I really like Nelson’s comparing this velocity of water to the velocity of money in a financial system.

Dr. Nelson Lebo III: Banks…what is there to say that hasn’t already been said? If you read the Automatic Earth, if you watch Max Keiser, if you’ve followed The Crash Course, there is no comment about financial institutions I can make that would add to the critique. That’s not my gig anyway. My gig is to offer realistic, achievable, grass roots, no-excuses alternatives to the dominant neoliberal consumerist paradigm. One approach I’ve gravitated toward over the years goes by the name of permaculture.

Permaculture has been around for decades. You’ve probably heard of it but do you know what it is? Yeah, that’s the problem. My observations are that the eco design methodology known as permaculture suffers in two fundamental ways: a confusing name and dogmatic application by inexperienced converts. The name is the name – no changing it at this point – and there is no antidote for dogma. But for a general audience of readers I’d like to lay out the ethics and practice of permaculture in the clearest ways possible – by using concrete examples.

Example One: The Permaculture Ethics

When engaging with permaculture as a design methodology, practitioners are bound to follow a simple code of ethics: care for the environment; care for people; and, share surplus resources. I appreciate this ethical code because it helps distinguish a permaculturist from anyone else who may be involved in some aspect of the ‘sustainability movement’ such as an organic farmer, recycler, green builder, eco-entrepreneur or local currency advocate.

This is not to say that a permaculturist cannot engage in all of these (indeed they do), but that anyone who practices one or more than these is not necessarily engaging with the permaculture ethics. Think of large-scale organic farms in California that truck in “certified organic” inputs and ship out bags of lettuce thousands of miles to the East Coast. Not permaculture.

People may take a permaculture course or buy a permaculture book for various reasons, but these do not necessarily make them a practicing permaculturist. I like to make the point that the difference between a permaculturist and a survivalist is 100 cases of baked beans and a gun. If you ain’t sharing, it ain’t permaculture.

I also appreciate the ethics because they are an integral part of the design process. In other words, the ethics can be used to help shape a larger project. An example of this is the ‘curtain bank’ that we recently opened in our community.

Those unfamiliar with curtain banks can be forgiven as many developed countries around the world have decent standards for housing that include high performance windows and central heating. But most of the New Zealand housing stock has been variously described as “sub-standard”, “abysmal”, “horrid”, and “a joke.” Mind you, that’s a bad joke instead of a funny one.

The majority of homes in this country are so cold that curtains must be used as a serious way to reduce heat loss. It is not uncommon for overnight indoor temperatures to drop into the mid-single-digits Celsius and daytime indoor temperatures to barely reach double-digits. I’ve heard stories of frost on the inside of windowpanes.

To add insult to injury, we also suffer from wealth and income inequality that make the purchase of new or even second-hand curtains out of reach for many families. As a result curtain banks have popped up in cities around the nation to redistribute second-hand curtains free of charge.

Applied Permaculture Ethics

Sharing surplus resources : People of means replace their curtains for various reasons, but most often for aesthetic ones. If the curtains are still in good condition and free of mould, they can be dropped off at the curtain bank, which makes them available for other households. Like any bank it accepts deposits and grants withdrawals. No fees. No contracts. No interest rates.

While traditional banks have the privilege to ‘lend money into existence’ we cannot lend curtains into existence, although it would be nice. We rely on donations from good people in our community to be passed on to other good people in our community. Which brings us to the next ethic.

Caring for people : It’s no secret that there is a link between sub-standard housing and illness in New Zealand. Sadly, most of the housing in our city is cold and/or damp. These unhealthy homes are especially hard on children and seniors. Many lack adequate curtaining.

Getting properly installed curtains, insulating blinds and window blankets into as many homes as possible helps make the occupants more comfortable and healthier. This is straight up caring for people by addressing some fairly basic needs.

Care for the earth : Improving the ‘thermal envelope’ of a home is the best way to save the energy required for heating and cooling. Saving energy is generally considered good for the environment by reducing carbon emissions or reducing the number of rivers dammed or even reducing the number of solar panels that need to be manufactured.

In these ways curtain banks tick all of the boxes for the permaculture ethics.

Example Two: Applied Eco-Design

The other example I’ll share is a direct application of eco-design: imitating nature to develop or reestablish robust ecological systems. The latter of these is sometimes called ‘regenerative design’.

Most of New Zealand is plagued by a legacy of bad farming practices most easily described as overgrazing steep slopes and allowing stock to foul streams.

We took possession of our small farm two years ago and have been working persistently to – dare I say it – ‘heal the land.’ Currently we are in the process of reestablishing a wetland and protecting the streams from stock. Additionally, we are planting native trees and poplar poles on steep hillsides to prevent slips, reduce erosion and provide bee fodder.

We are doing all this because that’s what nature wants. In other words, that’s the way the land was 1,000 years ago (less the non-native poplars) and given enough time that’s what it would revert to after the permanent removal of large hooved mammals. Our work just speeds up the process and allows for a continued agricultural function, which we are still figuring out.

All of this work is supported by our amazing Regional Council, which offers expert advice, low-cost poplar poles, and matching funding for fencing and native plantings. I cannot speak highly enough of these programmes. Horizons Regional Council does a fantastic job of looking at the big picture and applying holistic solutions. Unlike most government bodies and agencies, they get it.

Lake Horowhenua Planting Day

Forests and wetlands play important roles in moderating seasonal water flows across large land areas. In other words they store water high on the landscape during wet periods and release it slowly during dry periods. It works like a bank by accepting deposits and granting withdrawals.

Much of the farmland in our region suffers from extreme weather on both ends – wet and dry. Neither is good for stock, nor good for farmers, nor good for water quality, nor good for anyone living downstream. It’s a lose-lose-lose-lose situation and the reasons are clear: not enough trees on hillsides and streamsides. That’s basically it.

The solution is to build resilient waterways by imitating nature. Projects like ours are the best way that landowners and supportive communities can directly address the extreme weather events associated with a volatile changing climate.

The restoration work on our farm will help – to a tiny degree – everyone who lives and works downstream and downriver from us by keeping water out of the system during peak rain events. This is critical to our community that already faces tens of millions of dollars in repair bills from the last two major rain events that occurred just 13 months apart.

Given enough farmers with enough will and enough government assistance there is no reason we could not fence off all the streams in our region and plant all the steep hillsides to appropriate species. It’s much cheaper than cleaning up over and over again after serial flood events.

Alternative Banking

So what this is all about is developing alternative banking systems – stream banks and curtain banks among others – and getting communities involved. This is what resilience is all about (see also Resilience is The New Black and Climate, Energy, Economy: Pick Two)

This is the heart and soul of permaculture design thinking, and it is the best way to address the two biggest issues facing humanity: wealth inequality and climate change.

When I dip my toe into the financial news media on occasion I hear this phrase: “the velocity of money” as it pertains to the “health of the economy.”

I thought of the phrase the other day while meeting with a client on managing storm water on their large rural property after they had already done everything wrong. Yes, they had done absolutely everything wrong and I was trying to get them to understand that channelizing water only makes it go faster and cause more damage. The damage was obvious after the last major rain event – that’s why they called me in for an assessment.

As I explained the biological – rather than engineering – solutions, I felt we were going around in circles because they did not really want to hear what I had to say. They just wanted to be rid of the water. Sorry, but that’s not an option without over half a million dollars to spend on massive underground drains, which don’t solve the problem but simply pass it on to everyone downstream. And besides, they don’t have the money anyway.

Finally, I simply said, “The only possible solution is to slow the water and spread the water. It’s the only way to stop the damage.”

And that has me thinking. Should we apply the same approach to dollars?

I reckon a critical piece of the puzzle for neglected rural economies like ours is to slow and spread the flow of money as much as possible before it inevitably drains back to the major centres of power and wealth.

Dorothea Lange wrote about the photograph at the top, back in November 1938:

“Home of rural rehabilitation client, Tulare County, California. They bought 20 acres of raw unimproved land with a first payment of 50 dollars which was money saved out of relief budget (August 1936). They received a Farm Security Administration loan of $700 for stock and equipment. Now they have a one-room shack, seven cows, three sows, and homemade pumping plant, along with 10 acres of improved permanent pasture. Cream check approximately 30 dollars per month. Husband also works about ten days a month outside the farm. Husband is 26 years old, wife 22, three small children. Been in California five years. ‘Piece by piece this place gets put together. One more piece of pipe and our water tank will be finished’. From Shorpy.