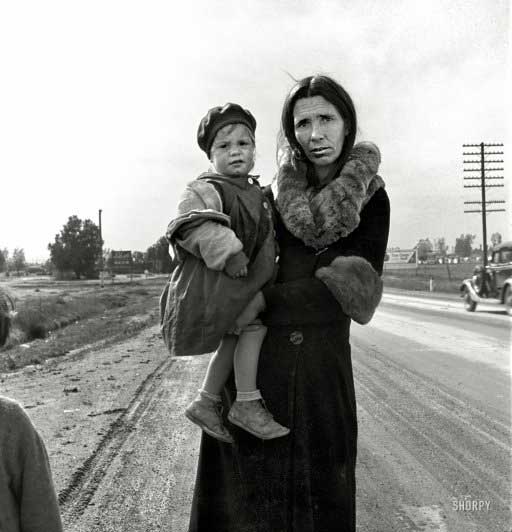

Dorothea Lange Route 99 February 1939

"On U.S. 99 near Brawley, Imperial County, California. Homeless mother and youngest child of seven walking the highway from Phoenix, Arizona, where they picked cotton. Bound for San Diego, where the father hopes to get on relief 'because he once lived there.'"

As everything connected to Europe seemed to fall apart even before US jobs numbers were announced, and we could say I told you so a thousand times when it comes to debt deflation and crunching credit and the rise of the US dollar, but won‘t, there's a piece by Jeremy Warner at the Telegraph that I think I should mention.

First, though, I see that Nassim Taleb says he'd much rather invest in Europe than the US. While I can see where he's coming from, so to speak, I don't think he's from Europe. He talks about "a lot of fun currencies" that could replace the Euro, but ignores the potential battlegrounds that lie between the Euro and the European "fun" currencies that may or may not sprout from its demise. Down the line, sure, he may have a point, but it's important to think about at what point he may have that point. The US dollar has some strength to come yet.

As you probably know, The Automatic Earth is not about investment advice, we're not here to make people richer; we want to try to save them from abject poverty. And the future will show us painfully clearly that that is not such an easy thing to do. If only because as long as things look normal or alright or at least hopeful, give it a name, people don't tend to be preoccupied with protecting themselves against poverty. Jeremy Warner provides yet another reason why they should. If you think unemployment numbers are high now, you might want to rethink that.

Warner writes about an S&P report that estimates the amounts industrialized nations' industries need to finance and refinance over the next four years, About $10 trillion a year on average. Where will they turn to borrow this money? Not to the banks, one would argue: they need to borrow just as hard to stay afloat. Governments? Surely you're joking, Mr Sixpack.

Ergo: companies worldwide will need to downsize and "reform". That is debt deflation, guys, that is a credit crunch. These things hurt something bad, and there's no escaping it. Bailing out banks while at the same time bleeding industries dry and shedding jobs like so many flies won't help anything recover.

Now, obviously there are lots of healthy companies that will be fine. But please note that the S&P report sets aside a substantial part (roughly a third) of the financing for "growth". It seems crystal clear that we can forget about that. Growth doesn't rhyme with crunch. Jeremy Warner:

A $46 trillion problem comes sweeping in

Just as you thought things couldn't get any worse, credit markets are about to be hit by a veritable tsunami of maturing corporate debt. Standard & Poor's estimates that companies in Europe, the US and the major Asian economies require a combination of refinancing and new money to fund growth over the next four years of between $43 trillion and $46 trillion. The wall of maturing debt is unprecedented, raising the prospect of further, extreme difficulties in credit markets.

With the eurozone debt crisis still at full throttle, the Chinese economy slowing fast and a still tepid US recovery, it's not clear that the banking system is in any position to deal with this incoming wave of demand.

Warner then for some reason veers off into a rant against regulation and in particular against the European commissioner for internal markets, Michel Barnier. Liquidity requirements make refinancing harder, that sort of thing. Well, it all depends on what level of fractional reserve banking you think is normal, doesn't it? And if holding no reserves to speak of is the only way for banks to "spur growth", perhaps we should take a step back and ask ourselves what on earth we're doing. Liquidity requirements can be a good thing; just ask Jamie Dimon and his London Whale. Or better yet, ask the depositors of many major banks, who see their deposit insurance threatened if not eroded. See below for more. First, a bit more from Warner:

In its analysis of the refinancing challenge, S&P concedes that it might just about be possible for the banking system to cope with the wave of corporate debt maturities, assuming no further deepening of the eurozone crisis. But providing the $13 trillion to $16 trillion of new money to spur growth is going to be a much bigger ask, especially in Europe.

European banks, still grappling with high leverage and a worsening sovereign debt crisis, are particularly badly affected. Because of the escalating European banking crisis, they face intense pressure to meet new capital and liquidity requirements more quickly. With new equity virtually impossible to raise, this has only further exaggerated the de-leveraging problem. Enforced recapitalisation from governments which are themselves insolvent scarcely helps matters.

In the US, there is at least a highly developed corporate bond market to act as an alternative to bank funding. That's not the case in Europe, where to the contrary, the regulatory agenda seems determined to put as many obstacles in the way of a viable bond market as possible.

Standard & Poor's calculates that if corporate issuers in Europe were to tap the bond market for 50pc of their new funding requirements (up from 15pc historically), it would imply net new yearly issuance of $210bn to $260bn. In only two years in the last decade has net new European issuance exceeded $100bn.

You might think this a significant growth opportunity, but Mr Barnier's new solvency directive threatens to snuff that one out too, by requiring that only the most credit worthy and liquid bonds count for capital purposes.

The new solvency requirements virtually outlaw bundling together corporate loans and issuing them as asset backed securities, or rather, they prevent financial institutions from providing a viable source of demand for such bonds. Instead, finance is pushed by regulation ever more aggressively into sovereign bonds, even though many of them are now less than credit worthy.

Yeah, Mr. Warner, asset backed securities, that wonderful innovation that has made us all so rich…. We certainly need more of those. And I’m not saying we need more sovereign bonds, I’m saying we need less of everything that can be acquired only through borrowing. Not easy, no, you're right, but easy is not on the menu. It would be short term easier to for instance build more highways with private money. But who would use those highways? Oil usage in the US and Europe is already plummeting. What says we can, or indeed should, revive it?

The rules also threaten to stymie Government hopes of the private sector substituting for the public infrastructure spending being cut as part of the austerity drive. Many long dated infrastructure bonds don't meet the investment grade deemed necessary to qualify as a "safe" investments for insurers.

A more nonsensical piece of regulation is hard to imagine. Public investment in infrastructure is being cut almost everywhere to meet deficit reduction targets, leaving EU member states highly reliant on private sector funding for essential investment in the future.

Governments could of course do as the CBI suggests in a new report on infrastructure spending, and either guarantee the bonds or enhance their credit rating by entering into first loss agreements, but this is just off-balance sheet window dressing, where the private sector takes the upside, and taxpayers the downside. Governments might as well spend the money themselves.

Europe desperately needs growth, but it seems determined to stifle the credit needed to provide it. How stupid can you get?

Call me back if and when your vocabulary expands beyond "growth“, Jeremy. We need a broader perspective.

Right, so, those depositors. Lefteris Papadimas and George Georgiopoulos had this for Reuters:

Greece Gives Banks $22.6 Billion As Exit Panic Causes Savers To Pull Funds

Greece handed 18 billion euros ($22.6 billion) to its four biggest banks on Monday, the finance ministry said, allowing the stricken lenders to regain access to European Central Bank funding. The long-awaited injection – via bonds from the European Financial Stability Facility rescue fund – will boost the nearly depleted capital base of National Bank, Alpha , Eurobank and Piraeus Bank.

"The bridge recapitalization of the four largest Greek banks was completed today with the transfer of funds of 18 billion Euros from the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF)," the finance ministry said in a statement. "This capital injection restores the capital adequacy level of these banks and ensures their access to the provision of liquidity funding from the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem. The banks have now sufficient financial resources in support of the real economy." [..]

Greek state coffers are on track for a more than 10 percent fall in revenue this month, a senior finance ministry official said last week. Officials had warned the state could run out of cash to pay pensions and salaries by end-June. [..]

Huge writedowns from a landmark restructuring to cut Greece's debt nearly erased the capital base of its biggest four banks, which rely on the ECB and the Bank of Greece to meet their liquidity needs, after savers began pulling their cash out on fears that Greece could go bankrupt and out of the euro zone.

Last week the ECB stopped providing liquidity to some Greek banks because their capital base was depleted. With access to wholesale funding markets shut on sovereign debt concerns, Greek banks have been borrowing from the ECB against collateral, and from the Greek central bank's more expensive emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) facility.

Bleeding deposits, the country's lenders have borrowed 73.4 billion euros from the ECB and 54 billion from the Bank of Greece via the ELA as of end-January. Together, the sums translate to about 77% of the banking system's household and business deposits, which stood at about 165 billion euros at the end of March.[..]

Key details of the recapitalisation plan for Greece's battered banking sector, including the mix of new shares and convertible bonds to be issued, and whether call options will be included as incentives, remain unclear.

In other words: there's nothing left, so they pass some virtual money around to make things look good a few weeks more, or months perhaps. The only way Greek banks can be kept barely alive (or, if you will, the only way the dead can be kept on their feet for a while longer) is through emergency injections of capital (bonds) underwritten by all Eurozone citizens (and the rest of the world through the IMF). The money first moves from the European Financial Stability Fund to the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund, and then on to the banks, because direct funding of banks is not allowed in Europe. Or perhaps we should say: not allowed yet.

Still, as all banks use (and/or already have used) their best assets as collateral for ECB loans, like LTRO, thereby shoving their other creditors and shareholders into the bleachers, the financing situation can only get worse. So people taking money out of their accounts seems the only possible consequence, in a vicious circle of self-fulfilling false prophecies.

And no, it's not just Greece, if that's what you might have thought. Now, let's make one thing clear once more: deposit insurance is useless in all but a theoretical manner. It can make people feel good, but it won't do them any actual good when push comes to shove. Liam Vaughan and Gavin Finch write for Bloomberg:

Greek Exit From Euro Seen Exposing Deposit-Guaranty Flaws

The threat of Greece exiting the euro is exposing flaws in how banks and governments protect European depositors’ cash in the event of a run.

National deposit-insurance programs, strengthened by the European Union in 2009 to guarantee at least 100,000 euros ($125,000), leave savers at risk of losses if a country leaves the euro and its currency is redenominated. The funds in some nations also have been depleted after they were used to help bail out struggling lenders, leading policy makers to consider implementing an EU-wide protection plan.

"These schemes were not designed to deal with a complete meltdown of a banking system," said Andrew Campbell, professor of international banking and finance law at the University of Leeds in the U.K. and an adviser to the International Association of Deposit Insurers. "If there’s a systemic failure, there needs to be some form of intervention."

With European officials openly discussing a Greek exit from the euro for the first time, savers in Spain, Italy and Portugal may start to withdraw cash on concern that those countries will follow Greece and their funds will be devalued with a switch to a successor currency. None of those nations has the firepower to handle simultaneous runs on multiple banks.

Households and businesses pulled 34 billion euros from Greek banks in the 12 months ended in March, 17 percent of the country’s total, according to the ECB.

Deposits at banks in Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain fell by 80.6 billion euros, or 3.2 percent from the end of 2010 through the end of March, ECB data show. German and French banks increased deposits by 217.4 billion euros, or 6.3 percent, in the same period. Bank-deposit data for April will be released starting this week.

"Contagion fears might compel individuals in Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain to withdraw bank deposits due to concerns over solvency, redenomination, or otherwise," UBS AG (UBSN) Chief Investment Officer Alexander Friedman said in a May letter to client advisers. "This could spark a major banking collapse, requiring truly unprecedented action from the ECB." [..]

"An EU-wide deposit-guarantee fund may prove to be the most important tool to preserve financial-market stability if Greece were to leave the euro area," said Tobias Blattner, an economist at Daiwa Capital Markets in London. [..]

Policy makers also may consider cutting interest rates, buying more bonds through the EU’s Securities Market Program and starting a third longer-term financing operation to stem concerns that the currency may break up, Stefan Nedialkov, a London-based analyst at Citigroup Inc. wrote in a May 17 note.

Savers pulled 27 percent of deposits from Argentina’s banks between 2000 and 2003 during a currency crisis, Nedialkov wrote. If Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain follow a similar pattern, about €340 billion could be withdrawn, he estimated.

Companies have already started to remove cash from southern Europe as soon as they earn it. Many already are sweeping funds daily out of banks in those countries and depositing it overnight with firms in the U.K. and northern Europe, according to David Manson, head of liquidity management at Barclays Plc in London, who advises company treasurers.

"There is a spectrum of perceived risk, which starts with Greece on one end and Germany and the U.K. on the other," Manson said. "Portugal, Italy and Spain are all somewhere in the middle of that spectrum. This trend of sweeping deposits north has been exacerbated by the current crisis."

"For a pan-euro deposit-guarantee scheme to ‘firewall’ deposits in Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain following a potential Greek exit, it needs to explicitly cover redenomination risk as well," Ronit Ghose, a Citigroup analyst based in London, wrote in a May 25 report. That would cost more than 150 billion euros, he estimated.

Seeing that Spanish banks alone are estimated to be at risk for some €270 billion, one would tend to agree.

The European Commission said in a July 2010 report that a pan-European deposit guarantee would be cheaper and more effective than individual national facilities, though legal issues made it a "longer-term project" to be reviewed by 2014.

The EU currently is weighing plans to force national governments to ensure that a minimum amount of money is immediately available to stabilize a bank in the event of a run. Under the proposals, to be published by the commission June 6, funds would be raised through annual contributions by banks. Lenders could be tapped for further financing in an emergency, then national central banks, before governments would be obliged to lend to each other as a last resort.

Member states could merge these requirements with existing national arrangements to guarantee bank deposits, and would also be required to pool financial resources when a cross-border bank is on the point of failure, according to a draft of the plans obtained by Bloomberg News on May 25. [..]

Italy’s deposit-insurance program is still unfunded, with banks pledging to contribute if and when necessary [!!!]. Silvia Lazzarino De Lorenzo, a spokeswoman for Roberto Moretti, chairman of the Interbank Deposit Protection Fund, declined to comment. The country had 1.1 trillion euros of deposits at the end of March, ECB data show.

Portugal has a deposit fund of 1.4 billion euros collected from banks through annual contributions, according to Barclays. The country’s total deposits stood at 164.7 billion euros at the end of March, according to the central bank.

"The real difficulty is that domestic consumers in countries like Germany will be forced to pony up for the failures of foreign banks," Gleeson said. "That makes it politically very difficult."

Deposit insurance in those European countries that are presently experiencing mass withdrawals (Spain announced €100 billion was withdrawn from its banks so far this year) is grossly inadequate: Italy’s deposit-insurance program is still unfunded, with banks pledging to contribute if and when necessary [!!!].

And there are those who want a pan-European insurance? And ask the Dutch and the Germans to insure Italian depositors to the tune of €100,000 or more per capita? And the Portuguese? The Spanish? Surely you're joking. Northern Europeans have insurance on-paper-only themselves. That is never going to fly.

There are politicians in Holland working on a scheme that would lead to a split Euro, a northern one and a southern one. That, too, is not going to happen. If only, for one thing, because they won't be able to decide in which segment France should ge placed. There is no solution. Nature, reality, will solve this mess. Not people. And reality can be a harsh mistress.

Home › Forums › The truth about Europe – There is no solution Part 2: Growth doesn’t rhyme with crunch