Carl Mydans Auto transport at Indiana gas station May 1936

And once again, the financial media insist that the most important issue in the entire world are a bunch of numbers arrived at in very questionable fashion: US jobless rates. As a journalist, the safe thing to is to parrot all others, so you don’t stick out, and no-one can accuse you of being wrong without saying that about everyone else. Well, bring ’em on, let’s see either losses on account of disappointing numbers or losses on account of upward surprising numbers and subsequent more tapering.

While those are the available reactions on Wall Street, on Main Street the only number to watch is the labor participation rate. Though it has reached such absurd territory recently that one can be excused for wondering what exactly it reflects anymore. (Update: disappointing jobs growth – 110,000 – , unemployment rate keeps falling anyway to 6.6%)

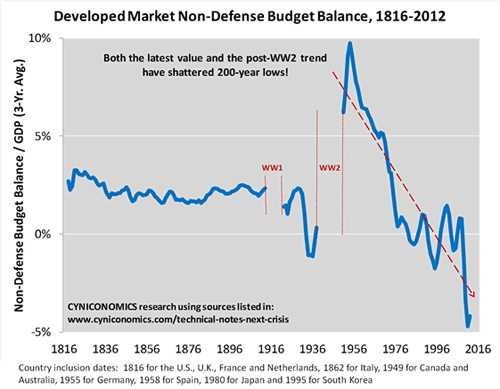

A rarely reviewed but relevant, and for Main Street certainly more interesting than anything BLS, number comes from Cyniconomics (h/t ZH): global non-defense budget balance, aka plain vanilla fiscal responsibility. Why non-defense? Because “Military spending requires a different evaluation because it succeeds or fails based on whether wars are won or lost. Or, in the case of America’s adventures of the past six decades, whether war mongering policies serve any national interest at all.”.

And why focus on fiscal responsibility? Because “Governments of winning economies normally meet their debt obligations; losing economies are synonymous with fiscal crises and sovereign defaults. [..] … a lack of fiscal responsibility is a sure sign of economic distress (think banana republic).

Few people, in all likelihood, will be overly surprised to see that a graph showing fiscal responsibility in 11 of the world’s richest countries looks the way it does (it probably closely resembles that of the US labor participation rate over the past decade):

Now, of course you could argue that “responsibilty” is an abstract term, but the graph depicts some pretty solid and interesting notions.

My interpretation would be something like: through the nineteenth century, even as we know there were a few hefty financial crises, 1844, 1873, fiscal responsibility hardly wavered, no doubt the gold standard played a large role in this. There were severe rumblings involving gold in the first few decades of the 20th century, but isn’t until the interregnum that we see the first real drop.

Then for a few years after WWII, everyone’s recuperating and rebuilding, but it doesn’t take long: everyone wanted to emulate the US, and from the early 50s to the early 70s, that’s only 20 years, there was so much growth that most politicians, hey, most everybody, lost all sense and responsibility.

Again, that’s only 20 years of real growth. All the rest has essentially been borrowed. In 1971, President Nixon ended the international convertibility of the dollar to gold. At the end of the 70s (after the oil crises), a new found responsibilty seems to form, for maybe 10 years, but then the plunge takes off. It starts to dawn on everyone that they can simply borrow against their paper – and increasingly just electronic – currencies.

Which at first doesn’t have all that bad an effect, until about 15 years ago, when the next realization comes: not only can you borrow against paper and keystroke entries, you can then use it to purchase “assets”, and borrow 10-100 times more than these are worth. Financial innovation, sanctioned and brought to you by the Greenspan cabal. Growth as a theater performance, masterfully delivered by a bunch of real life Gordon Geckos, Bill Clinton and W. The financial-political-industrial system was born and that line hasn’t stopped dropping yet.

Have they learned yet? Have we? You nuts, have you seen how deeply they’re all in debt, and how fast that debt grows? The US will soon pay $1 trillion in interest on its debt. That’s your money, the fruits of your labor, flowing right into the financial industry. Like so much of your money does in so many ways. The only thing they’ve learned is how to devise ways to get access to more of the honey, money’s way more addictive than heroin.

The question is: where will this lead from here? There’s a little uptick at the very end of the graph, but that’s just the recent asset bubble, blown -again – with borrowed funds. Yes, governments borrow from banks when they issue bonds, but they first hand the banks the funds to buy the bonds with. How could a 21st century western government fund itself if it didn’t do that? And, more importantly, how could a government wean itself off such a destructive addiction?

A British group named Positive Money have an idea (and no, they’re not the first): imagine if we updated the laws so that banks were prohibited from creating both paper and electronic money. 90-odd% of money today is credit, and it’s created when banks hand out loans for mortgages and other loans. Which is why a housing crisis bites both GDP numbers and banks so much, and why they try with all their might to blow another bubble.

But this money/credit could simply be issued by the government, which wouldn’t have to pay interest on it either. Everybody better off except for bankers, but perhaps our purpose in life isn’t really to make bankers happy. The bigger issue with this idea might be who we would want in our governments that we can trust with issuing it. There are very few left in today’s cabinets and parliaments who are not beholden to the financial industry. So you would, right from the get go, have to ban money from politics, or nothing changes other than in name.

Not easy, but the alternative is to see the downward trend in that graph continue and worsen. Even if through some miracle we would see economic growth, it’ll just be swallowed up by the banking system. There’s no way out of the growth labyrinth for Main Street anymore.

We might as well ask ourselves why we insist on growth, why we invariably see Wall Street gains as positive, why up is always good and down is always bad. It’s the mindset that leads to what you see in that graph, and the whole picture painted around it, and it can only get worse, because it doesn’t have a mechanism for self-correction. Allow too few people too large a piece of the pie, and they’ll keep wanting more. The larger system will “self-correct” in the end through outside factors, but that will lead to the sort of pain only very few of us would volunteer for.

• The Next Global Crisis Will Be Unlike Any In The Last 200 Years (Cyniconomics)

Sometime soon, we’ll take a shot at summing up our long-term economic future with just a handful of charts and research results. In the meantime, we’ve created a new chart that may be the most important piece. There are two ideas behind it:

1) Wars and political systems are the two most basic determinants of an economy’s long-term path. America’s unique pattern of economic performance differs from Russia’s, which differs from Germany’s, and so on, largely because of the outcomes of two types of battles: military and political.

2) The next attribute that most obviously separates winning from losing economies is fiscal responsibility. Governments of winning economies normally meet their debt obligations; losing economies are synonymous with fiscal crises and sovereign defaults. You can argue causation in either direction, but we’re not playing that game here. We’re simply noting that a lack of fiscal responsibility is a sure sign of economic distress (think banana republic).

Our latest chart isolates the fiscal piece by removing war effects and considering only large, developed countries. In particular, we look at government budget balances without military spending components. (Military spending requires a different evaluation because it succeeds or fails based on whether wars are won or lost. Or, in the case of America’s adventures of the past six decades, whether war mongering policies serve any national interest at all. In any case, military spending isn’t our focus here.)

There are 11 countries in our analysis, chosen according to a rule we’ve used in the past – GDP must be as large as that of the Netherlands. We start in 1816 for four of the 11 (the U.S., U.K., France and Netherlands). Others are added at later dates, depending mostly on data availability. (See this “technical notes” post for further detail.) Here’s the chart:

Not only has the global, non-defense budget balance dropped to never-before-seen levels, but it’s falling along a trend line that shows no sign of flattening. The trend line spells fiscal disaster. It suggests that we’ve never been in a predicament comparable to today. Essentially, the world’s developed countries are following the same path that’s failed, time and again, in chronically insolvent nations of the developing world.

Ambrose and Albert Edwards: they’re not going to let go of the deflation theme. As well they shouldn’t.

• Deflation shock-wave from Asia to trigger global recession (AEP)

Albert Edwards from Societe Generale has returned from two weeks holiday in a completely foul mood. “The ongoing emerging market debacle will be less contained than sub-prime ultimately proved to be. The simple fact is that US and global profits growth have reached tipping point and the unfolding EM crisis will push global profits and thereafter the global economy into deep recession.”

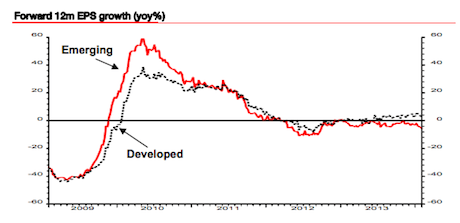

What we are seeing is a “direct replay” of the East Asia crisis of 1997 but on a bigger scale. A strong dollar/weak yen world is an “incendiary mix” for emerging markets. It tightens liquidity while delivering a trade shock to weaker economies. Analysts are slashing their forecasts at an “all-time record rate – this is wholly inconsistent with talk of economic acceleration”. “The dire profits situation will only get worse as EM implodes and waves of deflation flow from Asia to overwhelm the fragile situation in the US and Europe.”

This week’s slump in America’s ISM manufacturing gauge is the “straw in the wind” of what is to come. “Even if the Fed resumes massive QE at some point as the world melts down, and markets desperately attempt their return to the dream trance, they will instead find themselves locked into a Freddy Krueger-like nightmare in which phase 3 of this secular bear market takes equity valuations down to levels not seen for a generation.”

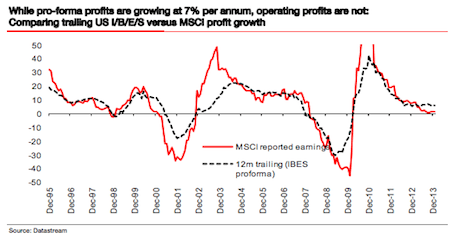

Albert and SG’s Andrew Lapthorne say profits have already slumped to near zero growth if you use MSCI reported earning rather than the “made-up” pro-forma IBES data.

EM profits have been negative for two years already. The global equity rally has been driven by QE fumes.

I hate to think what would happen if Albert were right. The world cannot take such an outcome in its present enfeebled condition. It would push China into a dangerous crisis, greatly raising the risk a diversionary military clash with Japan, which would in turn embroil the US in a Pacific War. It would doom any chance of recovery in southern Europe, sending debt trajectories and jobless rates through the roof. The European Project would disintegrate in acrimony, with a chain of sovereign defaults pushing Germany into depression. Britain would spin into another financial cataclysm, this time having to rescue banks with huge exposure to emerging markets and China (through Hong Kong). This would be hard to explain to long-suffering British taxpayers a second time.

Regulators bothering you about conforming to such petty thingies as laws? We have ways!

• Shadow banks account for more than 25% of US mid-size business loans (RT)

SA quarter of US mid-sized businesses with less than half a million dollars in annual revenue, and a locomotive of the US economy, are sourcing loans from shadow banks pushing out the more traditional lenders.

In 2013 main street banks provided 73% of middle-market loans, which is a decrease from 81% the year before, and the lowest share since 2006, cites Thomson Reuters data. Non-bank lenders such as business development companies (BDC) and hedge funds have filled the vacuum which was created after a regulatory crackdown on some banks’ riskiest loans, the FT explains.

Last year the biggest banks were warned to avoid making unsafe leveraged loans the Federal Reserve and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency were mostly concerned about. The regulators criticized 42% of the 496 reviewed leveraged obligors, while the overall portfolio criticized rate was 10%. The term “leveraged loan” is used to describe loans to companies and individuals that already have considerable debt. This makes such loans especially risky which reflects in higher interest rates.

The Fed’s quarterly survey of loan officers says US banks had further “eased their lending policies for commercial and industrial (C&I) loans” in terms of “increased competition,” as they are forced to compete with more lightly-regulated entities. “Some leveraged loans had been curtailed or significantly altered by the guidance, but a majority of them believed that affected borrowers would be able to turn to other sources of funding,” says the survey.

“We are hearing that banks are passing on deals that have a high chance of being criticized by regulators, especially if they are not leading the deal,” the Financial Times quotes Fran Beyers, a senior market analyst at Thomson Reuters.

Americans by now have a wide choice of issues they should be ashamed of.

• Senate GOP blocks new bid to restore jobless benefits (Reuters)

U.S. Senate Republicans on Thursday blocked a new bid by Democrats to restore long-term unemployment benefits for 1.7 million Americans, and make millionaires ineligible for such aid.

On a largely party-line vote of 58-40, Democrats fell short of the needed 60 votes to clear a Republican procedural hurdle against a three-month, retroactive extension of the relief that would be fully paid for and not increase the federal debt. Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid, expecting defeat, declared before the vote that his party would keep trying, saying, “We are not going to give up on the unemployed.”

The court sees “important reasons to assume that it exceeds the European Central Bank’s monetary policy mandate .. “, i.e. it’s illegal, but it refers it to the European Court, which will take a few years studying it, so for all practical intents and purposes this means the ECB can execute this potentially hugely expensive and presumably illegal scheme with impunity. At least the German court should provide a proper definition of the “important reasons to assume” the whole thing is illegal. Either that or they should be sent home dressed – only – in shame, tar and chicken intestines.

• German judges refer ECB’s bond buying scheme to European Court (Reuters)

Germany’s Constitutional Court said on Friday it had decided to refer a complaint against the European Central Bank’s (ECB) “unlimited” bond-buying program to the European Court. The ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program, announced by ECB chief Mario Draghi in September 2012 at the height of the sovereign debt crisis, is widely credited with stabilizing the euro.

The court said it sees “important reasons to assume that it exceeds the European Central Bank’s monetary policy mandate and thus infringes the powers of the member states, and that it violates the prohibition of monetary financing of the budget”. However, the court said in a statement that it “also considers it possible that if the OMT Decision were interpreted restrictively” it could conform with law. The German court said it will rule on the legality of the currency bloc’s permanent bailout scheme, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), on March 18.

Ambrose again, prolific days. As I said yesterday, I think Draghi’s simply scared sh*tless by now. Brussels’ new tack is to ridicule the very term “deflation”. Looks desperate, and I predict that won’t last long.

• Split ECB paralysed as deflation draws closer (AEP)

The European Central Bank has brushed aside calls for radical action to head off deflation and relieve pressure on emerging markets, denying that the eurozone is at risk of a Japanese-style trap. Yields on German two-year notes almost doubled to 0.12% as markets slashed expectations for future rate cuts, while the euro spiked 1.5 cents to more than $1.36 against the dollar, implying a further tightening of monetary conditions for Europe.

Mario Draghi, ECB president, said the bank is “alert to the risks, and stands willing and ready to act” if inflation falls even further below target or if the fragile recovery falters, but offered no clear guidance on future policy. Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas, Barclays and RBS had all expected a cut in the main interest rate, while there had been widespread reports that the ECB would open the door to quantitative easing – allegedly by halting “sterilisation” of its €175bn bond holdings.

“Monetary policy in the eurozone is incredibly tight and is doing real damage to the economy, yet they do absolutely nothing. It boggles the mind,” said one former ECB governor. “The idea that everything is alright because they are not in actual deflation is a false premise. They are already so far below their 2% target that it is causing much higher unemployment and making it that much harder for the eurozone periphery to adjust. I am afraid to say that Mario Draghi has been captured by the German political class. He doesn’t want to compromise the support of Angela Merkel’s government,” he said.

Bourses in Europe and the US rallied strongly despite the disappointment but tell-tale fractures in financial markets call for caution. Simon Derrick, from BNY Mellon, said the sharp rise in the Japanese yen – typically the early warning signal for trouble – has echoes of events in the build-up to the Lehman crisis. “Given the huge bubble we’ve seen in emerging markets, the combination of Fed tightening and a hawkish ECB that refuses to act makes this all too like 2007, even if the risks are in a different place. One misstep now could be the trigger,” he said.

Mr Draghi said the ECB’s council had discussed a wide range of measures but needed more information, adding that the “complexity of the situation prevented action at this time”. Core inflation has already fallen to 0.6% once tax rises are stripped out. The M3 money supply has been contracting at a 1% rate over the past three months, against a target of 4.5% growth. “They are not fulfilling their basic mandate. They are letting deflationary forces become embedded in the system just like Japan in the 1990s,” said Lars Christensen, from Danske Bank. “The rhetoric is even the same. The Bank of Japan kept denying that they were going into deflation, and kept insisting that monetary policy was accommodative when it was fact too tight,” he added.

Mr Draghi said the bank is paying “close attention” to the deflation risk, which raises the bar even higher for states in southern Europe trying to push through austerity and structural reform. However, he denied that the trap is already being set : “Is there a deflation? The answer is no. We don’t see any similarity with Japan in the 1990s. It’s completely different,” he said. Mr Draghi said 60% of the items in inflation basket were falling in Japan at the time. The slide is much narrower in the eurozone, and has not acquired the same “self-feeding” character. “We have to dispense with this idea of deflation,” he said.

When German exports fall, that’s a big deal for Europe, and most anyone else. But to paraphrase Groucho, if you don’t like the numbers, well, I have others. You don’t like December, why not add it to last January? Hence, headlines such as these: “German exports fall in 2013, but trade surplus widens”. “German trade surplus soars to all-time high despite easing in exports”. “German trade surplus dips in December, hits full-year record”.. Anything goes in the world of media. Anything to keep the “leaders” happy. No difference there between China and the west world.

• German Exports Post Surprise Fall In December (DPA)

German exports posted a surprise fall in December, bringing to an end four consecutive monthly gains, the Federal Statistics Office said Friday. Monthly exports from Europe’s biggest economy fell by 0.9% in December after gaining 0.7% in November. Analysts had expected a rise of 0.8%. Imports also dropped unexpectedly in December, by 0.6%, after contracting by 2.3% in November, the data showed. Analysts had forecast a 1.2% increase.

This resulted in the calendar and seasonally adjusted trade surplus narrowing to €18.5 billion ($25.13 billion) in December from €18.9 billion in November. For the full year, exports slipped by 0.2% while imports dropped by 1.2% compared with 2012. This represented the first full-year fall in exports since the 2009 recession. Germany’s trade balance widened year on year to a record €198.9 billion, the statistics office said.

“German December industrial orders fall but upwards trend intact”. More of the same. Tell your kids to train to become spin doctors, they’ll be set for life.

• German Industrial Output Unexpectedly Decreased in December (Bloomberg)

German industrial output unexpectedly fell in December, signaling that Europe’s largest economy remains vulnerable to weakness in the rest of the region. Production, adjusted for seasonal swings, decreased 0.6% from November, when it rose a revised 2.4%, the Economy Ministry in Berlin said today. Economists predicted a gain of 0.3%, according to the median of 40 estimates in a Bloomberg News survey. Production rose 2.6% from a year earlier when adjusted for working days.

While the Bundesbank predicts Germany’s economy will expand “strongly” in the first months of 2014, turmoil in emerging markets and a fragile recovery in rest of the 18-nation euro area, the nation’s largest trading partner, could weigh on output. German factory orders unexpectedly declined in December, even though business confidence is at a 2 1/2 year high. Manufacturing output declined 0.5% in December from the previous month and investment-goods production fell 2.5%, according to today’s report.

These guys just about blew up the entire country, just to make their bank – and themselves – look better. Kudos to Ireland for hauling them in. Who’s next, please?

• Anglo Irish Execs On Trial For Massive Loan Fraud (RT)

Three Anglo Irish Bank execs face 16 charges connected to €625 million in loans made to wealthy clients in a scheme which attempted to prop the bank up during the 2008 financial crisis. This marks the start of the Ireland’s biggest corporate legal trial.

Sean Fitzpatrick, the banks’ former chairman, Pat Whelan, former Chief Financial Officer, and William McAteer, former finance and risk director, “broke Irish company law” in 2008 when issuing loans to a group of wealth investors, which included Ireland’s once-richest man Sean Quinn, in order to buy shares in Anglo Irish. The scheme was an attempt to cut down the nearly 25% share Quinn held in the bank, because the bank was worried about being “exposed to the fortunes of one man,” according to prosecutor Paul O’Higgins’ opening statement.

Whelan faces additional charges connected with altering loan documentation. All three men have pleaded not guilty to all the charges. The case is drawing lots of public attention with hundreds outside the Dublin Central Criminal Court on Wednesday. The trial is expected to last for months.

The bank played a huge role in nearly bankrupting the country, which was forced to accept a €67.5 billion bailout from European lenders during the banking crisis of 2008-2009. Taxpayers provided Anglo Irish with €30 billion to keep the bank solvent. Anglo Irish has been renamed the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation, and is still in the process of being liquidated, as the austerity-hit country awaits a number of high-profile cases involving the collapse of the bank.

A separate case against executives recorded joking about how they duped the government to give them bailout money with no plans to pay back, is still under investigation.

See my intro.

• Simple change to the money system could solve long-term economic problems (Guardian)

Exactly 170 years ago, the UK government passed a law to deal with a banking crisis that was uncannily similar to the one we’ve just endured. Updating that law may hold the key to preventing the crisis from happening again.

The Bank Charter Act 1844 prohibited anyone other than the Bank of England from printing paper money. Before it was passed, high street banks had been handing out pieces of paper as receipts for the metal coins that people deposited with them. Over time, the paper receipts became accepted as being as good as the coins, and were used as though they were money. Borrowers would sign loan agreements and accept a piece of paper with the bank’s name on it, rather than asking for coins issued by the Royal Mint. In a stroke of luck, bankers had acquired the power to literally print money.

Naturally, banks found it hard to resist the temptation to make more loans by simply printing more paper money. The credit bubble that resulted – and the subsequent bust – prompted the government to prohibit banks from creating money in the form of paper notes.

But the 1844 law was never updated to apply to electronic money and still only applies to paper notes. Metal coins and paper notes now make up just 3% of all the money in the UK. The remaining 97% of money consists of essentially numbers in high street banks’ computer systems. Banks create this electronic money through a simple accounting process whenever someone takes out a loan.

In the decade preceding the financial crisis, banks created more than a trillion pounds of new money – and new debt – this way. Of this new money, 51% went straight into property, artificially inflating house prices, with salaries unable to keep up. A further 32% went into the financial markets, fuelling good times for the City but storing up problems for the future. Just 8% went to the non-financial businesses that create jobs and employment, and a further 8% went on personal loans and credit cards.

Now imagine if we updated the laws so that banks were prohibited from creating both paper and electronic money. Instead, electronic money could be created directly by the Bank of England and added to the central government’s bank account. The government would then put that money into the real economy, through government spending or tax rebates.

It could even give everyone their equal share – an idea described as quantitative easing (QE) for the people. Instead of flooding property and financial markets, money created in this way could start its life in the real economy, boosting GDP and employment rather than inflating house prices and household debt burdens.

Thailand loses $12 billion on a rice scheme that locked them out of international markets . They would make Madoff proud. 17% of global rice stocks is in Thai warehouses. And it’s rotting. If you thought the recent elections were bad, you may have another one coming.

• Rice debacle could spell the end of Thai government (Fairfax)

Just when beleaguered Thai prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra needs them most, rice farmers have angrily turned against her and joined protests that threaten to topple her government. “All of the people in my district supported Yingluck in the past but now none of us do,” says Narumol Klysiri, a 55 year-old farmer holding a receipt for seven tonnes of rice she sold to the government four months ago. “Where is my money? My family has no money to eat,” she says.

Mrs Narumol is one of more than one million farmers who have not being paid for months as a rice subsidy scheme that helped sweep Ms Yingluck into power in 2011 teeters on collapse, with losses that economists say could be as high as $12 billion. Thousands of farmers have been left in deep debt and there are reports of increasing rural suicides.

Many economists, academics and public figures have criticised the scheme, whose losses threaten to downgrade Thailand’s credit rating. Economists estimate it costs more than $9 billion a year to run the scheme – about 2.5% of gross domestic product.

The fiasco began with the government’s attempt two years ago to manipulate the world’s rice market. Thailand was at the time the largest exporter of rice, which is not just a staple in the country, but an object of respect. The plan was to buy local rice harvests for as much as 50% above market rates to drive up global prices. But the market saw it as a clumsy attempt at price manipulation.

Rice exporters such as Vietnam and India stepped up their production while Thai exporters responded by investing in emerging producers such as Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos. Global prices stayed low and the Thai government amassed stockpiles rather than selling overseas at a steep loss. Thailand effectively priced itself out of the market.

Warehouses across the country are full with rice stockpiles estimated at 18 million tonnes, 17% of total global stocks. Its quality is deteriorating the longer it stays there and there are reports some is already rotten. Early this week China cancelled a deal to buy more than a million tonnes of the rice, citing the anti-corruption agency’s probe into the scheme.

Once China grinds to a halt, and it imports stutter, maybe Australia can use it ensuing crisis to get rid of their present Canberra bunch. And make sure they get some actual human beings in return.

• Australia government ‘taking an axe’ to environment (Guardian)

Labor says expert advice it received when in government raised major concerns over whether dredged sludge should be dumped near the Great Barrier Reef, and accuses the Coalition of “taking an axe” to Australia’s environment since taking office.

Mark Butler, Labor’s environment spokesman, told Guardian Australia that a government-commissioned report placed a “serious question mark” over the proposal to dredge 3m cubic metres of seabed in order to enlarge a coal port at Abbot Point in Queensland. Butler received the information during his spell as environment minister. He deferred the decision on whether to allow the dredging shortly before Labor lost last year’s election.

The Coalition subsequently approved the dredging and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority last week gave the go-ahead to dump the dredged material within the boundaries of the world heritage-listed ecosystem. Butler said the report “cast serious doubt” on reassurances that dumping dredged sand, silt and clay wouldn’t damage coral reefs, dolphins, dugongs and other animals.

“It showed that material was liable to be spread much longer than I had been previously advised, and for much further distances than I was advised,” he said. “From my point of view, the report placed a serious question mark over the proposal. I’m concerned we don’t know what happened to this report. I’m not sure [environment minister] Greg Hunt has answered the questions raised by it.”

Butler said he was “gravely concerned” that Unesco’s world heritage committee would place the Great Barrier Reef on its “in-danger” list when it meets in Doha in June, accusing the government of placing 60,000 tourism jobs and Australia’s international reputation at risk with its “cavalier” attitude towards the reef.

This article addresses just one of the many issues discussed in Nicole Foss’ new video presentation, Facing the Future, co-presented with Laurence Boomert and available from the Automatic Earth Store. Get your copy now, be much better prepared for 2014, and support The Automatic Earth in the process!

Home › Forums › Debt Rattle Feb 7 2014: Why Is Up Always Good And Down Always Bad?