Ansel Adams Nurse Hamaguchi 1943 “Nurse Aiko Hamaguchi at the Manzanar Relocation Center, California”

Stoneleigh:

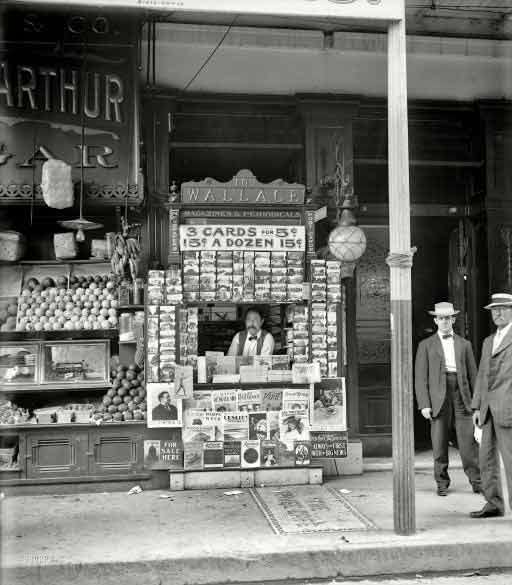

Welcome to The Atomic Village

“Denko-chan (でんこちゃん), whose name comes from the “den” of electric power (電力, denryoku), the “ko” (子, child) in which female names so often end, trapping their bearers in a state of eternal childhood, and the generally female diminutive suffix “chan”, can be found everywhere in TEPCO propaganda. Here she is, with finger characteristically a-wagging, admonishing us to “Take care of electricity!””

Stoneleigh: These days, Denko-chan is perhaps more representative of the situation that the country and TEPCO find themselves in when rendered like this, in fan art:

As an energy resource poor island, Japan has embraced nuclear power over the last several decades as a means to ensure security of energy supply. Growth in electricity supply was a key enabler of the Japanese post-war boom and commitment to high-tech industrial growth, but dependence on external sources would have entailed a major vulnerability. The oil shocks of the 1970s strongly underlined the danger of dependency on potentially unstable or capricious foreign suppliers, creating further impetus for nuclear development. The relative independence and self-sufficiency conferred by nuclear development also fitted with a characteristic Japanese cultural insularity. Prior to the earthquake and tsunami, nuclear provided over 30% of Japan’s electric power from 54 reactors.

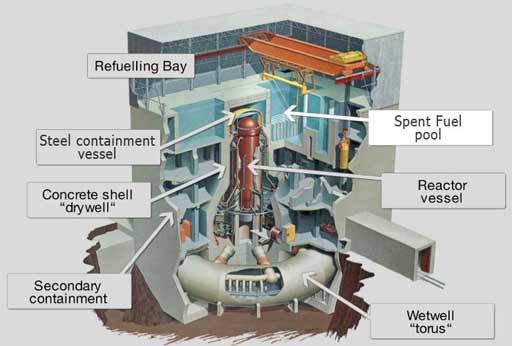

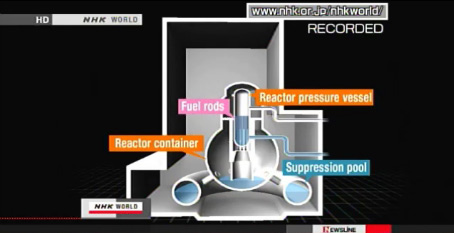

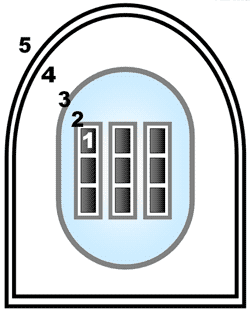

Since the disaster of March 11th, the world has been watching Japan struggle to deal with an unanticipated eventuality that greatly exceeded the design-basis accident for the 40-year old Fukushima plant and overwhelmed its inadequate defences. Japan is in uncharted waters, attempting to control several badly damaged reactors and several spent fuel pools simultaneously, under circumstances for which there is no rule book to follow. Criticism is mounting as to the way the catastrophe is being handled, and the Japanese nuclear governance record is coming under sharp scrutiny.

In order to fathom the Japanese approach to these events, it is necessary to understand aspects of Japanese culture, especially as it manifests in terms of corporate culture.

People’s sense of identity and worth is tightly bound with membership of strong, cohesive groups. Japan is an insular and collectivist society which prizes conformity, loyalty, harmony, obedience, consensus, teamwork, stability and homogeneity, and strongly discourages deviation from the norm or standing out from the crowd. Originality, initiative, freedom of expression and openness to outside influences are therefore not generally rewarded. There is an old Japanese proverb encapsulating this attitude:

出る杭は打たれる。(“Deru kui wa utareru“), or in English, “The stake that sticks up gets hammered down.“

Sociologist Geert Hofstede:

Individualism on the one side versus its opposite, collectivism, that is the degree to which individuals are integrated into groups. On the individualist side we find societies in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after him/herself and his/her immediate family.

On the collectivist side, we find societies in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, often extended families which continue protecting them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. The word ‘collectivism’ in this sense has no political meaning: it refers to the group, not to the state.

Stoneleigh: In the corporate world, loyalty to one’s firm, and to the team effort, is expected to be demonstrated by sacrifices such as working long hours and not taking one’s allotted vacation. This has traditionally been rewarded with job security, wages which increase substantially with seniority, insurance, bonuses, pensions, access to company recreational facilities and low-cost loans. Group activities are encouraged, both on the job and after hours. The life of a salaryman is expected to revolve around the office. He is expected to share a strong emotional bond with his co-workers, and to share the attitudes and values of the group. Salarymen are sometimes unflatteringly referred to as 社畜 (shachiku), meaning ‘corporate livestock’.

Responsibility is collective, and the leadership role of top management is defined by the ability to maintain harmony and create consensus, rather than the making of bold decisions. Policy is shaped at the level of middle management. Actions leading to potential conflict are discouraged, because of the importance placed avoiding embarrassment or shame. Failing to fulfill one’s obligations to the group also results in loss of face in a culture where relationships, and the good opinion of others, are of the utmost importance.

This corporate culture applies particularly to large, first-tier, Japanese firms, such as TEPCO, where job security has been much stronger through Japan’s two decades of economic stagnation. Employment at such a firm is typically only open to graduates of Japan’s top thirty colleges and universities, hence much effort from a young age is invested in gaining entrance to one of these institutions. Doing so confers high status, which is extremely important (it influences everything from the depth of a bow on greeting, to the language style used, the gifts given, and the relationships formed). Hofstede:

Companies provide their own training and show a strong preference for young men who can be trained in the company way. Interest in a person whose attitudes and work habits are shaped outside the company is low.

Permanent employees are hired as generalists, not as specialists for specific positions. A new worker is not hired because of any special skill or experience; rather, the individual’s intelligence, educational background, and personal attitudes and attributes are closely examined. On entering a Japanese corporation, the new employee will train from six to twelve months in each of the firm’s major offices or divisions. Thus, within a few years a young employee will know every facet of company operations.

Seniority is determined by the year an employee’s class enters the company. Career progression is highly predictable, regulated, and automatic. Members of the same graduating class usually start with similar salaries, and salary increases and promotions each year are generally uniform. The purpose is to maintain harmony and avoid stress and jealousy within the group.

Stoneleigh: This kind of culture is weaker in second-tier firms, which cannot provide the same benefits as a reward for loyalty. It weakens further as one descends strong social hierarchy, which exists as a relic of the old feudal caste system. Business elites expect to have a job and support structure for life, but at the other end of the social spectrum exists considerable, and sometimes hereditary, disadvantage. For instance, Burakumin (village people) are descendants of outcast communities from the feudal era, considered to have been tainted by their ancestral professions (executioners, undertakers, workers in slaughterhouses, butchers or tanners). Wikipedia:

They were legally liberated in 1871 with the abolition of the feudal caste system. However, this did not put a stop to social discrimination and their lower living standards, because Japanese family registration (Koseki) was fixed to ancestral home address until recently, which allowed people to deduce their Burakumin membership. The Burakumin were one of the several groups discriminated against within Japanese society.

Stoneleigh: Other disadvantaged groups include residents of yoseba, or downwardly-mobile communities for day labourers, who are generally single, aging and low-skilled. “As they are increasingly transient, without a fixed address, they are denied access to communal and welfare services which in the past helped them to survive.”

In the context of tackling the Fukushima disaster, this hierarchy appears to play a significant role:

Job offers come not from TEPCO but from Mizukami Kogyo, a company whose business is construction and cleaning maintenance. The description indicates only that the work is at a nuclear plant in Fukushima Prefecture. The job is specified as 3 hours per day at an hourly wage of 10,000 yen. There is no information about danger. Those who answer these offers may have little awareness of the dangers and they are likely to have few other job opportunities. $122 an hour is hardly a king’s ransom given the risk of cancer from high radiation levels.

Rumor has it that many of the cleanup workers are burakumin. This cannot be verified, but it would be congruent with the logic of the nuclear industry and the difficult job situation of day laborers. Because of ostracism, some burakumin are also involved with yakuza [members of organized crime syndicates].

Therefore, it would not be surprising that yakuza-burakumin recruit other burakumin to go to Fukushima. Yakuza are active in recruiting day laborers of the yoseba. People who live in precarious conditions are then exposed to high levels of radiation, doing the most dirty and dangerous jobs in the nuclear plants, then are sent back to the yoseba. Those who fall ill will not even appear in the statistics.

Stoneleigh: Prior to the devastation caused by the earthquake and tsunami, there was already a well established hierarchical subcontracting system in place:

These contract employees or temporary workers were provided by subcontracting companies: they range from rank and file workers who carry out the dirtiest and most dangerous tasks—the nuclear gypsies described in Horie Kunio’s 1979 book and Higuchi Kenji’s photographic reports—to highly qualified technicians who supervise maintenance operations. So even within this category, there is much discrepancy in working conditions, wages and welfare depending on position in the hierarchy of subcontracted tasks.

What is clear is that the contract laborers are routinely exposed to the highest level of radiation: in 2009 according to NISA, of those who received a dose between 5 and 10 millisieverts (mSv), there were 671 contract laborers against 36 regular employees. Those who received between 10 and 15 mSv were comprised of 220 contract laborers and 2 regular workers, while 35 contract workers and no regular workers were exposed to a dose between 15 and 20 mSv.

Since contract laborers move from one nuclear plant to another, depending on the maintenance schedule of the various reactors, they lack access to their individual cumulative dose for one year or for many years. NISA compiles only the cumulative dose for each nuclear plant. The result is that the whole system is opaque, thus complicating the procedure for workers who need to apply for occupational hazards compensation.

Stoneleigh: This 1995 documentary provides some interesting background on the topic:

Nuclear Ginza: Japan’s secret at-risk labor force and the Fukushima disaster

Back in 1995, the UK’s Channel 4 produced a 30-minute documentary on Japan’s nuclear industry and how they use disadvantaged people, including burakumin and other day laborers, to do manual labor inside their power plants. And by inside, I mean inside. Some were forced to work right next to the room where the core was kept, in the dark and drenched in sweat; one man tells how he was forced to mop up radioactive water with towels.

Watch additional video segments here

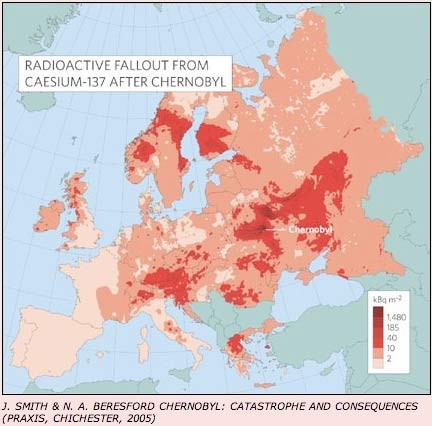

Stoneleigh: It may be very difficult to undertake any future epidemiological study of the health effects of Fukushima liquidators, as it was at Chernobyl where little data was ever collected. In the case of Chernobyl this willful blindness has allowed the official numbers for mortality and morbidity to be grossly underestimated. At Chernobyl there were hundreds of thousands of liquidators in the years following the accident, while at Fukushima the numbers are so far orders of magnitude lower.

Apparently, TEPCO is considering improving working conditions at the plant, but so far only in terms of food, showers and accommodation. There has been no mention of better radiation protection, even though workers have begun entering the reactor buildings:

Tokyo Electric Power Co (TEPCO) said it started work to install a ventilation system to clean the air inside the building at the Fukushima Daiichi plant.

Once the air inside is cleaned, TEPCO plans to send crews in to conduct complex work as part of attempts to bring the entire plant to a cold shutdown. It will be the first time workers have gone inside the building since the March 11 disaster.

The utility said it began installing tent-like equipment to keep radioactive materials inside the reactor one building when workers open its doors. The air inside the structure is highly contaminated with radioactive materials.

Stoneleigh: Discrimination against disadvantaged segments of society goes beyond feudal history and the workplace. In fact Fukushima is generating a new group to be marked as outsiders and treated accordingly in some quarters.

Don’t stigmatise nuclear evacuees, says Japan government

The Japanese government on Tuesday urged “heartless” people, local authorities and businesses not to discriminate against evacuees from the area around the crippled Fukushima nuclear plant.

The call came after some evacuation centres demanded radiation-free certificates from people who lived near the plant, and following reports that hotels have turned them away and their children have been bullied.

Since the March 11 earthquake and tsunami triggered the world’s worst nuclear crisis since Chernobyl, nearly 86,000 people have had to evacuate, with about 30,000 of them relocated outside Fukushima prefecture.

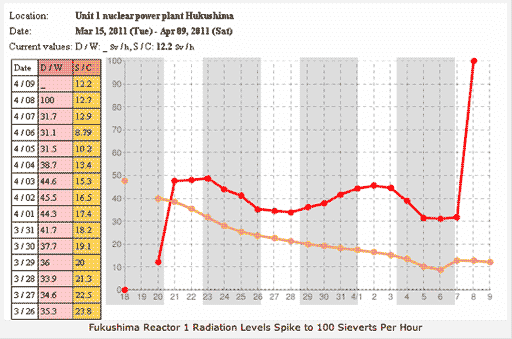

Stoneleigh: TEPCO’s management of the Fukushima crisis is being increasingly criticized, both externally and within Japan itself. For instance, the Soviet Army officer in change of the Chernobyl accident, Col-Gen Nikolai Antoshkin, has expressed shock at what he calls the “slow-motion” reaction at Fukushima. A few days after March 11th, TEPCO was evacuating 740 “non-essential” staff from the complex – leaving only 50 technicians to fight the worst civil nuclear crisis in Japan’s history. In contrast, a small army descended on Chernobyl in the days following the 1986 accident.

Several other foreign commentators, including Arnie Gundersen and Chris Busby, have also pointed out that Chernobyl was no longer emitting radiation into the environment after 6-7 weeks, while the Fukushima reactors are still doing so, and remain critically unstable. The continuing release of radiation will make the task of cleaning up ever more dangerous for the liquidators.

Michio Ishikawa, a veteran member of the Japan Nuclear Technology Institute who believes that all the reactors have melted down, has made a public stand on the issue of response adequacy as well. He describes the on-going disaster as a “war” and the efforts so far to cool the reactors as “peripheral tricks”. His assessment is stark indeed:

The water [inside the pressure vessel] is highly contaminated with uranium, plutonium, cesium, cobalt, in the concentration we’ve never seen before.

My old colleague contacted me and shared his calculations with me. At the decay heat of 2000 kilowatt… There’s a substance called cobalt 60. Highly radioactive, needs 1 to 1.5 meter thick shields. It kills people at 1000 curies. He calculated that there are 10 million curies of cobalt-60 in the reactor core. If 10% of cobalt-60 in the core dissolve into water, it’s 1 million curies [37,000 terabecquerels].

Stoneleigh: As Mr Ishikawa has indicated, TEPCO has consistently been reluctant to share information in its possession regarding the seriousness of the radiation release in the early days of the accident, ostensibly understating the seriousness in order to prevent panic.

It seems likely, given the defensive responses of an embattled company, that the lack of openness is at least partly due to corporate interests over-riding the broader public interest. When asked about the discrepancies between his view and the official story of limited core damage, Mr Ishikawa labelled the official line a lie. Perhaps because he is 77 years old, he no longer needs to be mindful of the effect that breaking ranks with the collective could have for him personally.

Japan Denies Withholding Evidence of Massive Radiation Release

Japan on Tuesday [a month after the accident] upgraded the plant’s incident level from 5 to 7, a classification reserved for the most severe nuclear crises. The government took the action in large part in response to calculations showing that extreme quantities of radioactive iodine and cesium had escaped from the six-reactor facility in the first week after it was crippled by the 9.0-magnitude earthquake and devastating tsunami that hit Japan on March 11.

Uncertainty over the calculations’ accuracy held up their release, Japanese Nuclear Safety Commission official Seiji Shiroya said. In addition, the official suggested the government was concerned the measurements could exacerbate public fear over the atomic crisis.

“Some foreigners fled the country even when there appeared to be little risk,” Shiroya said. “If we immediately decided to label the situation as level 7, we could have triggered a panicked reaction.”

Stoneleigh: In addition to the delay in releasing vital information, some of the delay in making meaningful attempts to cool the damaged reactors is also attributable to corporate priorities over-riding the public interest:

Bid to ‘Protect Assets’ Slowed Reactor Fight

Crucial efforts to tame Japan’s crippled nuclear plant were delayed by concerns over damaging valuable power assets and by initial passivity on the part of the government, people familiar with the situation said, offering new insight into the management of the crisis [..]

The plant’s operator—Tokyo Electric Power Co., or TEPCO—considered using seawater from the nearby coast to cool one of its six reactors at least as early as last Saturday morning, the day after the quake struck. But it didn’t do so until that evening, after the prime minister ordered it following an explosion at the facility.

TEPCO didn’t begin using seawater at other reactors until Sunday. TEPCO was reluctant to use seawater because it worried about hurting its long-term investment in the complex, say people involved with the efforts. Seawater, which can render a nuclear reactor permanently inoperable, now is at the center of efforts to keep the plant under control.

Stoneleigh: It is not clear who is in charge, which is not surprising given Japan’s consensus-building culture. Yuki Tatsumi for BBC:

As the head of the disaster response headquarters, the prime minister has the authority to direct relevant government agencies as well as private companies that are involved in responding to the disaster.

He has two entities from which to draw expert opinions to assist him in decision-making: the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (Nisa, an agency within the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Trade (Meti) and the Nuclear Safety Commission, an advisory panel made up of non-government experts. So, legally speaking, the prime minister of Japan is in charge. Or he is supposed to be.

So what of Mr Kan’s leadership to date? On the one hand, it has been clear that he wants to appear in charge: he wanted to “speak directly to the Japanese people” in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake. Four days after the quake, amid confusion over the situation at the plant, he was overheard by journalists asking TEPCO executives: “What the hell is going on?” [He could not understand why he had not been told for a whole hour about the first explosion at the plant.]

Demonstrating his distrust in TEPCO and Meti, he has appointed a number of non-government experts in addition to those who are already in advisory roles. As of 29 March, 5 out of 15 advisers were appointed specifically to advise on the situation at the plant.

Stoneleigh: One of these advisors has already submitted a tearful high-profile resignation:

During a press conference held at the Diet building later that day, [Tokyo University Professor Toshiso] Kosako, who was named a special advisor to Prime Minister Naoto Kan on March 16, criticized the government’s handling of the crisis at the Fukushima No. 1 Nuclear Power Plant as shortsighted.

In particular, Kosako protested against the government’s decision to revise the maximum permissible level of radiation exposure among children up to 20 millisieverts per year, saying, “Should I approve that decision, I would no longer be a researcher. I would not want my children to be exposed to that amount of radiation.”

Kosako revealed the Cabinet did not accept his advice that outdoor school activities for elementary and junior high school students near the crippled power station be restricted to prevent them from being exposed to over 1 millisievert of radiation per year.

“It is quite rare for nuclear power plant workers dealing with radioactive materials to be exposed to 20 millisieverts of radiation per year. I cannot allow infants and children to be exposed to such high levels of radiation from an academic as well as humanitarian point of view.”

He also pointed out that the government was slow in applying the System for Prediction of Environmental Emergency Dose Information (SPEEDI) and disclosing its data, even though nuclear safety guidelines stipulate the system be implemented immediately in an emergency. “The government has ignored the law and taken stopgap measures, failing to bring the crisis under control promptly,” he said.

Stoneleigh: For Professor Kosako to resign a very prestigious advisory position and to be so overtly critical of authority is highly unusual in a Japanese cultural context, and quite likely to have significant consequences for him personally. As the proverb says, the stake that sticks up gets hammered down. The professor had intended to conduct a press conference to explain his position in detail, but was prevented from doing so by the Prime Minister’s office.

Kan Administration Silences Prof. Toshiso Kosako with “Kindly” Advice on Confidentiality

Professor Toshiso Kosako of Tokyo University, who resigned on April 30 in protest over the 20 milli-sieverts per year allowable radiation exposure to children, was threatened with a “kindly advice” from the Prime Minister’s Office not to hold a press conference on May 2 to explain his opposition.

The “kindly advice” told Professor Kosako that he still has a confidentiality obligation not to disclose any information that he was privy to during his days as a special advisor to the Prime Minister.

Stoneleigh: Haruki Madarame, head of the Nuclear Safety Agency, recently expressed puzzlement at Professor Kosako’s concern:

I only know what’s reported in the newspapers, but honestly, I haven’t a clue as to why Professor Kosako is so upset.

Stoneleigh: International research supports Professor Kosako’s position:

Save the Children: Radiation Exposure of Fukushima Students

For infants (under 1 year of age) the radiation-related cancer risk is 3 to 4 times higher than for adults; and female infants are twice as susceptible as male infants. Females’ overall risk of cancer related to radiation exposure is 40 percent greater than for males. Fetuses in the womb are the most radiation-sensitive of all.

The pioneering Oxford Survey of Childhood Cancer found that X-rays of mothers, involving doses to the fetus of 10-20 mSv, resulted in a 40 percent increase in the cancer rate among children up to age 15. In Germany, a recent study of 25 years of the national childhood cancer register showed that even the normal operation of nuclear power plants is associated with a more than doubling of the risk of leukemia for children under 5 years old living within 5 kilometers of a nuclear plant.

Increased risk was seen to more than 50 km away. This was much higher than expected, and highlights the particular vulnerability to radiation of children in and outside the womb. In addition to exposure measured by typical external radiation counters, the children of Fukushima will also receive internal radiation from particles inhaled and lodged in their lungs, and taken in through contaminated food and water.

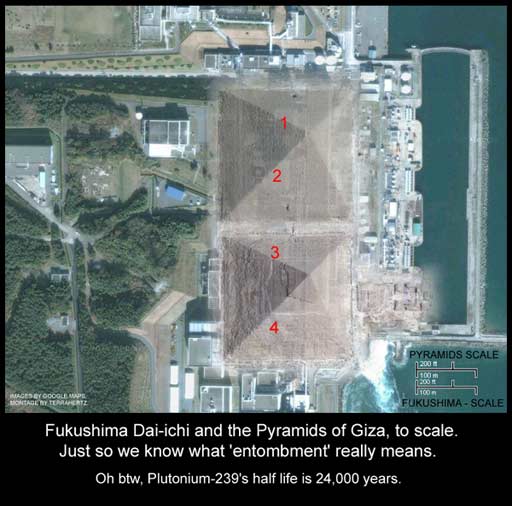

Stoneleigh: At least Japan has, a month after the disaster, implemented a mandatory exclusion zone. Five additional communities will be added to the zone within the next month. In some of these communities, radiation levels are already nearly double the threshold for mandatory evacuation in the Ukraine following Chernobyl. Discussions round the issue of compensation for the victims of Fukushima are already being held, although with the crisis still unfolding, it cannot be clear what compensation will be required:

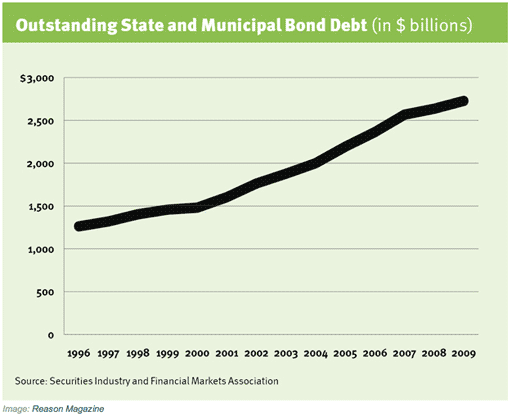

The Japanese government has estimated that compensation for damages resulting from the country’s nuclear crisis could reach four trillion yen ($49 billion), a report said Tuesday.

Half the money will come from Tokyo Electric Power Co (TEPCO), the operator of the crippled Fukushima Daiichi power plant, with the rest coming from other electricity companies, the Asahi Shimbun said, without citing sources [..]

TEPCO — which supplies about one third of Japan’s total power demand and services the Kanto region, including Tokyo — would increase its power tariffs by 16 percent, the Asahi said.

In addition, the government believes it will cost 1.5 trillion yen to decommission the six reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi plant and 1.0 trillion yen to fuel thermal power plants to meet electricity demand, the Asahi said.

Stoneleigh: TEPCO is already making plans to cut costs in order to meet this open-ended liability:

The operator of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant will implement deep salary cuts for management to help fund its compensation payments for the nuclear accident.

Tokyo Electric Power Company said on Monday that it would halve the salaries of all its board members, including the chairman and the president, starting this month. Annual pay for other executive directors will be slashed by 40 percent. The company will cut the salaries of about 3,000 employees in managerial positions by 25 percent.

TEPCO has already asked its labor union to accept a 20 percent reduction in annual pay for 32,000 rank-and-file employees. Both sides reached an agreement on the matter on Monday. The utility expects the measures to save some 660 million dollars in salary costs.

TEPCO will also give up its recruitment of about 1,100 new graduates for fiscal 2012 and sell off part of its stock holdings and real estate to raise money.

The company plans to make initial payments worth more than 600 million dollars to 50,000 households that have been forced to leave their towns to avoid high radioactivity caused by the nuclear accident. But the total compensation amount is expected to balloon, as damage is spreading to the farming, fisheries and manufacturing industries.

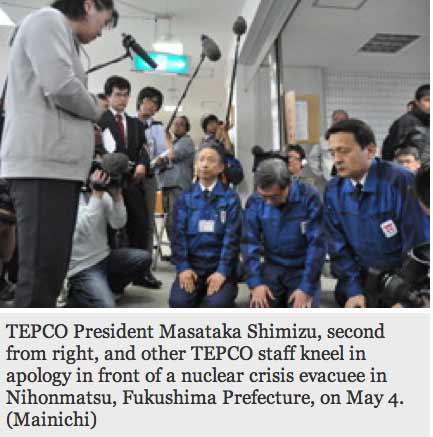

Stoneleigh: In addition, abject public apologies have been made to evacuees:

Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) President Masataka Shimizu was on his knees here on May 4, apologizing to residents of towns forced to evacuate by the Fukushima nuclear crisis [..]

Shimizu also visited the Adatara Gymnasium here, where about 100 nuclear crisis refugees from Namie are now living. There, he was showered with criticism and demands once more, including, “Get us back to our normal lives quickly,” and “You told us nuclear power was safe. Was that a lie?”

Shimizu responded by saying, “From my heart I apologize to you for betraying your trust.”

Stoneleigh: Unfortunately, betraying the trust of one’s company, in the culture of the loyal company man, or even one’s wider industry, has traditionally been considered a greater sin than betraying the trust of the public. The nuclear industry as a whole, including the regulator, has been particularly insular, defensive, and self-protective, leading to being labelled as ‘The Atomic Village’. The impenetrable Atomic Village has been a law unto itself for decades, with the result that the history of Japanese nuclear power is one of accidents, cover ups and complicity in the betrayal of the public trust. A harsh light is now being focused on a shameful history that hides behind cheerful cartoon mascots.

After the earthquake: In the nuclear village (genshiryoku mura, 原子力村, )(Please read the whole article.)

Initially baffled and obliged to translate it, I asked the author, an expert in the electric power industry, what it meant. It refers, he explained, to the insularity and secretiveness of the nuclear-industrial complex, the close-knit web of ties that bind the supervisory ministry, the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, the lapdog watchdog under the ministry, the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, the power companies, and the suppliers of the nuclear kit, prominent among them Hitachi, Toshiba, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

This village mentality (mura ishiki, 村意識) is a microcosm of the national insularity encapsulated in a more familiar phrase, “island nation spirit” (shimaguni konjo, 島国根性), and it demands unwavering loyalty to the—in this case nuclear—cause, on pain of being subject to ostracism (mura hachibu, literally “village eight parts”, 村八分), in which in its original sense, those who infringed the codes and order of the village were excluded from eight of the ten social activities deemed essential to the life of the village, the only exceptions being firefighting—to prevent a fire spreading from the home of the ostracized—and funerals—those of the ostracized themselves.

Culture of Complicity Tied to Stricken Nuclear Plant

In 2000, Kei Sugaoka, a Japanese-American nuclear inspector who had done work for General Electric at Daiichi, told Japan’s main nuclear regulator about a cracked steam dryer that he believed was being concealed. If exposed, the revelations could have forced the operator, Tokyo Electric Power, to do what utilities least want to do: undertake costly repairs.

What happened next was an example, critics have since said, of the collusive ties that bind the nation’s nuclear power companies, regulators and politicians.

Despite a new law shielding whistle-blowers, the regulator, the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, divulged Mr. Sugaoka’s identity to Tokyo Electric, effectively blackballing him from the industry. Instead of immediately deploying its own investigators to Daiichi, the agency instructed the company to inspect its own reactors. Regulators allowed the company to keep operating its reactors for the next two years even though, an investigation ultimately revealed, its executives had actually hidden other, far more serious problems, including cracks in the shrouds that cover reactor cores.”

“In Japan, the web of connections between the nuclear industry and government officials is now popularly referred to as the “nuclear power village.” The expression connotes the nontransparent, collusive interests that underlie the establishment’s push to increase nuclear power despite the discovery of active fault lines under plants, new projections about the size of tsunamis and a long history of cover-ups of safety problems.

Just as in any Japanese village, the like-minded — nuclear industry officials, bureaucrats, politicians and scientists — have prospered by rewarding one another with construction projects, lucrative positions, and political, financial and regulatory support. The few openly skeptical of nuclear power’s safety become village outcasts, losing out on promotions and backing.

Until recently, it had been considered political suicide to even discuss the need to reform an industry that appeared less concerned with safety than maximizing profits, said Kusuo Oshima, one of the few governing Democratic Party lawmakers who have long been critical of the nuclear industry.”

“At Fukushima Daiichi and elsewhere, critics say that safety problems have stemmed from a common source: a watchdog that is a member of the nuclear power village.

Though it is charged with oversight, the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency is part of the Ministry of Trade, Economy and Industry, the bureaucracy charged with promoting the use of nuclear power. Over a long career, officials are often transferred repeatedly between oversight and promotion divisions, blurring the lines between supporting and policing the industry.

Influential bureaucrats tend to side with the nuclear industry — and the promotion of it — because of a practice known as amakudari, or descent from heaven. Widely practiced in Japan’s main industries, amakudari allows senior bureaucrats, usually in their 50s, to land cushy jobs at the companies they once oversaw.

According to data compiled by the Communist Party, one of the fiercest critics of the nuclear industry, generations of high-ranking officials from the ministry have landed senior positions at the country’s 10 utilities since Japan’s first nuclear plants were designed in the 1960s. In a pattern reflective of the clear hierarchy in Japan’s ministries and utilities, the ministry’s most senior officials went to work at TEPCO, while those of lower ranks ended up at smaller utilities.”

“Collusion flows the other way, too, in a lesser-known practice known as amaagari, or ascent to heaven. Because the regulatory panels meant to backstop the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency lack full-time technical experts, they depend largely on retired or active engineers from nuclear-industry-related companies. They are unlikely to criticize the companies that employ them.

Even academics who challenge the industry may find themselves shunned. As Japan has begun looking into the problems surrounding collusion since March 11, the Japanese news media has highlighted the discrimination faced by academics who raised questions about the safety of nuclear power.

TEPCO Worker on Control Failures and the Culture of Silence

If my colleagues knew I was speaking with the press, they would despise me for it. My boss would certainly dismiss me. Therefore, I must remain anonymous. I have worked for TEPCO for a long time, and always considered it to be a good company. But now when I go to work, I see everywhere — on trains, on the streets — the headlines on the illuminated adverts for magazines: “TEPCO is bad, bad, bad.” That rankles because I know how much criticism it really deserves [..]

I know that new geo-scientific knowledge on earthquakes and tsunamis was ignored. In 2009, a research institute warned of the consequences of a disaster of equal magnitude to what has happened now. But the officials of the nuclear supervisory authority, NISA, didn’t take it seriously.

Controls in Japan don’t work. NISA falls under the control of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which also seeks to promote nuclear power. Isn’t it strange that the same authority both supervises and promotes nuclear plants?

Moreover, the nuclear scientists from industry and NISA know each other all too well. The circle of nuclear scientists is very small, and many have studied together. I have witnessed this in the workplace myself.

The nuclear department at TEPCO is already a very special group, forming a closed world. Some call it the “atomic village” — a separate company within a company. On the practical level, there is almost no exchange between the “atomic village” and other TEPCO departments.

This closed village has until now been allowed to hide data and test reports from nuclear power plants; to falsify and invent. For that reason, the president and the vice director resigned in 2002. The new head of TEPCO tried to open up the “atomic village” through transfers and restructuring, but everything is basically just the same.

Stoneleigh: Given the insular nature of the industry, it is hardly surprising that Greenpeace has been refused permission to take radiation measurements of water, sediment and marine life inside the 12 mile limit of Japan’s territorial waters. In a situation where lack of information, especially timely information, has been typical, the results of independent monitoring could help to protect the health of a population which typically consumes a large amount of seafood. However, it could also potentially embarrass TEPCO or provide a justification for future expensive compensation claims.

Marine radiation monitoring blocked by Japanese government

The sparse data published by the government and TEPCO is not enough to understand the real risks of the continuous leakage of radioactive water in the sea.

The Japanese people are in great need of independent information on the radioactive contamination of their seafood supply. Therefore, we are planning to do research on the radioactive contamination of seaweed, fish and shellfish.

Despite this great need for information, the Japanese government today refused a permit to do research within the territorial waters of Japan. We are allowed to conduct research outside this 12 mile zone, but this is not the area where the Japanese catch their fish and collect their seaweed.

This is a critical situation, so we are not giving up. We will continue heading for Fukushima to begin our research at a distance while we pursue further permission to carry out the sampling within the 12 mile limit.

The Japanese government should welcome such independent monitoring, the fact is they can never have enough information about the extent of the contamination, and the public are entitled to the benefit from the scrutiny and pressure that independent monitoring brings.

Stoneleigh: The Japanese nuclear industry has an uninspiring safety record, both in terms of accidents and the means in which accidents have been addressed. Thus far The Atomic Village has demonstrated much more commitment to protecting itself from scrutiny and potential criticism by outsiders than to learning from its collective mistakes. There is a long history of failing to undertake inspections, failing to provide adequate training, falsifying safety records, tampering with evidence, jury-rigging repairs that would have been expensive to carry out properly, operating with potentially unsafe equipment and failing to design for withstanding obvious risks. There is no evidence of an effective safety culture, nor of any attempt to be proactive with regard to risk minimization. It is useful to review some of the accidents in order to see how this has played out in practice. In addition, examining the history of the Fukushima plant itself is instructive.

Monju(December 8th, 1995, after only 4 months of operation)

Intense vibration caused a thermowell inside a pipe carrying sodium coolant to break, possibly at a defective weld point, allowing several hundred kilograms of sodium to leak out onto the floor below the pipe. Upon coming into contact with the air, the liquid sodium reacted with oxygen and moisture in the air, filling the room with caustic fumes and producing temperatures of several hundred degrees Celsius.

The heat was so intense that it melted several steel structures in the room. An alarm sounded around 7:30 p.m., switching the system over to manual operations, but a full operational shutdown was not ordered until around 9:00 p.m., after the fumes were spotted. When investigators located the source of the spill they found as much as three tons of solidified sodium. Fortunately, the leak occurred in the plant’s secondary cooling system, so the sodium was not radioactive.

The operator of a Japanese prototype fast-breeder reactor which was hit by a sodium leak had breached regulations by not immediately closing air ducts after smoke alarms went off, the Kyodo news agency said on Monday. Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corp (PNC) which runs the reactor, Monju, said it did not close air ducts until 3 1/2 hours after alarms went off. Regulations in the construction permit for Monju, submitted to the government, stipulate air ducts to be immediately closed when smoke alarms go off, the Kyodo news agency said.

For anyone wondering why shutting down the air conditioning is so significant in an accident like that, some more background. Burning Sodium can not be extinguished using water as it violently reacts with water, producing explosive hydrogen gas in the process. Halon and carbon dioxide (dry ice) based fire extinguishers can’t be used for a similar reason. The only way of putting out a sodium fire therefore is to starve it of all oxygen by cutting off the air supply and waiting for the fire to use up all oxygen.

Because of the danger of sodium fires, the primary coolant cycle where the sodium is highly radioactive is surrounded by inert nitrogen gas to reduce the chance of fires. Not so the secondary coolant cycle where the sodium fire occurred. By leaving the air conditioning on the operators of Monju kept pumping fresh oxygen into the room, fanning the flames of the burning sodium.

Panicked workers afraid to act without permission had worsened the initial leak by waiting 90 minutes to shut down the overheated system, officials admitted.

The PNC (called Donen in Japanese) which is controlled by the Japanese Science and Technology Agency had initially shown a 1 minute video of the accident site, later followed by another 4 minute clip and claimed that was all the footage that was available. None of this showed the actual coolant pipe that had leaked, only the floor of the site where the leak had occured. Later it was revealed that a total of 15 minutes of video had been taken, including footage of the affected pipe.

The one minute and four minute clips were only an edited version of the original clip. The existence of the unedited tape was kept secret for several days. It appears that the original tape had been deliberately edited to remove the footage of the leaking pipe. Asked for an explanation at a press conference of why the PNC had withheld information, Takao Takahashi, a board member of the PNC could only say: “There is none.” It also turned out that the PNC had inspected the site of the accident before the time given to the press.

Isao Sato, the deputy chief of the Monju office of the PNC admitted to giving orders to hide the master tapes of the video and to issuing gag orders to employees about the existence of the unedited originals. He was quoted as saying: “I was determined to cover up the case.”

Tokaimura Reprocessing Plant(March 11th, 1997):

A fire and explosion at the plant released a cloud of smoke possibly containing uranium and plutonium. Investigations disclosed that no fulltime plant employees were on duty at the time of the fire and seven maintenance workers were off-site playing golf. Smoke detectors had been turned off and the sprinkler system was not automatic — it had to be operated by hand.

Plant operators failed to warn nearby residents and even failed to evacuate 64 visitors who were on a tour of the plant when the fire broke out. When Prime Minister Hashimoto learned that the plant operators had lied to the government, he ordered a police raid on the company’s headquarters. Five officials eventually were demoted for falsifying reports.

Tsuruga(July 12th, 1999)

The coolant water leakage accident on July 12, at the second unit of the Tsuruga nuclear power plant (Japan) was not only one of the worst in terms of amount of primary coolant water that leaked (50 tons), but it is a significant accident because the crack that caused the leakage is different in nature from other power plant pipe cracks of the past.

The coolant leak at the Tsuruga reactor caused radiation levels inside the reactor building to shoot up 11,500 times the legal safety limit. This finding was announced by Japan Atomic Power Co. which operates the plant. At first, they said the highest level was about 250 times the limit (4 Bequerel per square centimeter set by Nuclear Reactors Control Law), but later they had to correct that figure. The highest level (46,000 Bequerel) was detected in a room on the second level basement, which is nine meters below the cracked pipe. The pipe in which the 4.4-cm long crack was found on July 12 was removed and closely examined. A second crack, 8 cm long, was found on the opposite side of the first crack. Later more cracks were found.

Tokaimura(September 30th, 1999)

On the day of the criticality accident, workers were running fuel through the last steps of the fuel purification process…. The JCO plant only needed to mix some high-purity enriched uranium oxide (U3O8) with nitric acid to form uranyl nitrate for shipping. During this operation, the workers deviated from the licensed procedure in three basic ways.

First, to speed up the process, they mixed the oxide and nitric acid in 10-liter buckets rather than in the dissolving tank (in doing so, they followed the practice that JCO had written into its manual—without Science and Technology Agency approval).

Second, for convenience, they added the bucket contents to the precipitation tank rather than to the buffer tank. That was a key misstep, because the tall, narrow geometry of the buffer tank precludes criticality.

Third, in filling the precipitation tank, the crew added seven buckets, or roughly seven times more uranium than permitted by the STA license. It was the seventh bucket that caused the mixture to go critical [..]

According to STA, the three workers in the room at the time the precipitation tank went critical received doses of 17, 10, and 3 sieverts. The entire JCO plant, not just the purification operation, was shut down, and STA revoked JCO’s operating license for the plant.

Stoneleigh: Two of the exposed workers died from lethal doses of radiation. Over forty others were treated for high level exposure, and hundreds of people living near the plant had to be temporarily evacuated from their homes

Mihama (August 9th, 2004)

A fatal accident happened at the Mihama No. 3 nuclear power station in Fukui prefecture, Japan. The plant is owned and run by Kansai Electric Power corporation (KEPCO), the major power utility in Western Japan. Four workers were scalded to death by superheated steam, seven other workers were injured.

The accident happened when the reactor was about to undergo routine maintenance. The accident was caused by a bursting steam pipe in the non-radioactive part of the reactor. In 27 years of operation that 56 cm diameter pipe had not once been checked for corrosion, let alone replaced. By the time it burst, its walls had worn down from an initial 10 mm of carbon steel to a mere 1.4 mm. Regulations required the pipes to be replaced when the walls were eroded to a thickness of 4.7 mm. Nine months before the accident a subcontractor company had alerted the operators to the need for inspections, but the warning was ignored.

Kashiwazaki-Kariwa(July 16th, 2007) World’s largest nuclear installation, with 7 reactors

A 6.8 earthquake [significantly larger than the design-basis accident for the plant], 10 kilometres offshore from the Honshu west coast plant, caused subsidence of the main structure, ruptured water pipes, started a fire that took five hours to extinguish, and triggered radioactive discharges into the atmosphere and sea. The company initially said there was no release of radiation, but admitted later that the quake had released radiation and had spilled radioactive water into the Sea of Japan. Seismologist Katsuhiko Ishibashi warned that had the epicentre been 10 kilometres to the southwest and at magnitude 7, Kashiwazaki City would have experienced a major emergency.

Monju (August 26th, 2010, only 4 months after restart following a 14 year hiatus of operations)

The accident involved a 3-tonne “fuel-replacement device” falling into the reactor vessel when being removed after a scheduled fuel replacement operation. According to Japanese Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA), the accident may result in a delay in bringing the reactor back into operation, since the device may have damaged the reactor vessel wall.”

Stoneleigh: The incident that most vividly illustrates the difficulty in establishing any kind of transparency or accountability in light of the tight-knit culture of the Atomic Village is the 1996 suicide of Shigeo Nishimura, deputy general manager of the general affairs department of the Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corp. (PNC), who had been charged with investigating the cover up of the first Monju accident. His actions represent a willingness to pay the highest price in order to remain loyal to his chosen collective.

He was tormented both by failure to get to the bottom of the cover-up and by the harm his inquiries would do to colleagues and the government corporation for which he worked for 26 years.

“They (PNC staff) were confident in their technical ability. But they may have found it difficult to explain their panic and confusion from the accident. It is most difficult for people to judge others and discover the truth,” Nishimura said in one of three suicide notes. He was investigating why plant officials took one hour to notify authorities about the leak and why video film of the incident was both edited and concealed from the press and government agency charged with determining what caused the leak.

Stoneleigh: The cover up culture does not apply only to the aftermath of accidents, but has also been demonstrated repeatedly in the conduct of day to day operations. What has emerged into the public domain is surely the tip of the iceberg, but it represents damning evidence of disregard for safety and the public interest on behalf of utility companies, regulators and the government.

Whistleblowers have been scapegoated, punishing the few who are prepared to risk disloyalty to their companies. Companies order staff to violate safety procedures or falsify data. Regulators turn a blind eye to violations, incompetence and failure to address obvious risks. Governments blindly push ahead with a one-dimensional agenda. Nuclear is meant to represent a shining new future, in contrast to remaining mired in a decaying past, but the foundations of that future have been built in a seismic zone, both literally and metaphorically.