Stanley Kubrick Shoe shine boys New York 1947

I wasn’t going to do a Debt Rattle at all. Too much time spent in too narrow and claustrophobic echo chambers. Bunch of loud shrieking parrots. But we have to move on. Tell people who think it all makes sense that really, it doesn’t. What you see is not what you get.

Economics is all about cycles. Central banks trying to deny and prevent them just makes the seasons more extreme.

• What Happens When Credit Spreads Finally Rise (ZH)

[..] according to one of the best minds on Wall Street today, Citi’s Matt King, what traders should be far more concerned about, is not who is in the Oval Office or how bombastic the war of words between the US and North Korea may be on any given day, but rather what central banks are preparing to unleash in the coming months. To underscore this, two weeks ago, King made a stark warning when he summarized that we are now more reliant on central banks banks holding markets together than ever before: “with asset prices displaying a high degree of correlation with central bank liquidity additions in recent years, that feedback loop makes the economy, upon which both corporate profitability and bank net interest margins depend, more reliant on central banks holding markets together than almost ever before. That delicate balance may well be sustained for the time being. But with central banks beginning to move, however gingerly, towards an exit, is it really worth chasing the last few bp of spread from here?”

One week later, he followed up with what was arguably his magnum opus on why the market is far too complacent about the threat to risk assets from the upcoming rounds of balance sheet normalization, summarized best in the following charts, showing the correlation between central bank asset purchases and the returns across global stock markets. The unspoken, if all too familiar, message was that riskier financial assets, such as credit and equities, have been artificially boosted by central bank actions, actions which are soon coming to an end whether voluntarily in the case of the Fed, or because the central bank is simply running out of eligible bonds to monetize, in the case of the ECB and BOJ.

In short, King is worried the global market is about to enter another tantrum. Is he right? To answer that question, another Citi strategist, Robert Buckland, admitting that “we are (always) worried”, takes a look at where we currently stand in the business cycle as represented by Citi’s Credit/Equity clock popularized also by Matt King in previous years.

For those unfamiliar, here is a summary of the various phases of the business cycle clock:

Phase 1: Debt Reduction – Buy Credit, Sell Equities Our clock starts as the credit bear market ends. Spreads turn down as companies repair balance sheets, often through deeply discounted share issues. This dilution, along with continued pressure on profits, keeps equity prices falling. For the present cycle, this phase began in December 2008 and ended in March 2009. Global equities fell another 21% even as US spreads tightened.

Phase 2: Profits Grow Faster Than Debt – Buy Credit, Buy Equities The equity bull market begins as economic indicators stabilise and profits recover. The credit bull market continues as improving cashflows strengthen company balance sheets. It’s all-round risk-on. This is usually the longest phase of the cycle. This began in March 2009, and according to most Wall Street analysts, is the phase we find ourselves in right now. Equity and credit investors both do well in this phase.

Phase 3: Debt Grows Faster Than Profits – Sell Credit, Buy Equities This is when credit and equities decouple again. Spreads turn upwards as fixed income investors become increasingly worried about deteriorating balance sheets. But equity markets keep rallying as EPS rise. Share prices are also boosted by the effects of higher corporate leverage, often in the form of share buybacks or M&A. This is the time to favour equities over credit.

Phase 4: Recession – Sell Credit, Sell Equities In this phase, equities recouple with credit in a classic bear market. It is associated with a global recession, collapsing EPS and worsening balance sheets. Insolvency fears plague the credit market, profit warnings plague the equity market. It’s all-round risk-off. Cash and government bonds are usually the best-performing asset classes.

More attempts at denial of cycles.

• Don’t Forget About The Red Swan (Stockman)

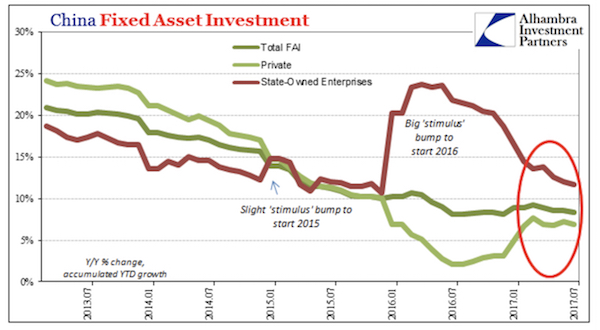

Given the anti-Trump feeding frenzy, we continue to believe that a Swan is on its way bearing Orange. But if that’s not enough to dissuade the dip buyers, perhaps the impending arrival of the Red Swan will at least give them pause. The chart below comprises a picture worth thousands of words. It puts the lie to the latest Wall Street belief that the global economy is accelerating and that surging corporate profits justify the market’s latest manic rip. What is actually going on is a short-lived global credit/growth impulse emanating from China. Beijing panicked early last year and opened up the capital expenditure (CapEx) spigots at the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) out of fear that China’s great machine was heading for stall speed at exactly the wrong time.

The 19th national communist party Congress scheduled for late fall of 2017. This every five year event is the single most important happening in the Red Ponzi. This time the event is slated to be the coronation of Xi Jinping as the second coming of Mao. Beijing was not about to risk an economy fizzling toward a flat line before the Congress. Yet that threat was clearly on the horizon as evident from the dark green line in the chart below which represents total fixed asset investment. The latter is the spring-wheel of China’s booming economy, but it had dropped from 22% per annum growth rate when Mr. Xi took the helm in 2012 to 10% by early 2016. There was an eruption as dramatized in the chart. CapEx growth suddenly more than doubled in the one-third of China’s economy that is already saturated in excess capacity.

The state owned enterprises (SOE) in steel, aluminum, autos, shipbuilding, chemicals, building equipment and supplies, railway and highway construction etc boomed. It was as if a switch had been flicked on by Mr. Xi himself, SOE CapEx soared back toward the 25% year-over-year rate by mid-2016, keeping total CapEx hugging the 10% growth line. However, you cannot grow an economy indefinitely by building pyramids or any other kind of low-return/no return investment – even if the initial growth spurt lasts for years as China’s had. Ultimately, the illusion of Keynesian spending gets exposed and the deadweight costs of malinvestments and excess capacity exact a heavy toll. If the investment boom that was financed with reckless credit expansion is not enough, as was the case in China where debt grew from $1 trillion in 1995 to $35 trillion today, the morning-after toll is especially severe and disruptive. This used to be called a “depression.”

China’s propagated spurt in global trade and commodities was artificial and short-term. It was done to flatter China’s rulers at the 19th party congress. Now that a favorable GDP glide path has been assured, China’s planners and bureaucracy are already back at it trying to find some way to reel in its runaway credit growth and bloated economy before it collapses.

Globalization dissected.

• Ricardo’s Vice and the Virtues of Industrial Diversity (Steve Keen)

That specialization is the primary source of economic gain has been accepted by economists ever since the famous example of the pin factory with which Adam Smith opened The Wealth of Nations: “One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; . . . ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day. . . . But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day.” David Ricardo extended Smith’s vision of specialization within a given industry to specialization between industries and nations, and made the argument that two countries can benefit from free trade even if one country is absolutely less competitive in both industries than the other.

In his hypothetical example, Portugal could produce both cloth and wine with less labor than England. If England specialized at the industry it was comparatively better at (cloth, obviously) and Portugal specialized in wine, then the total output of both industries would rise. This concept of the advantages of specialization became the core insight of economics, and it continues to be ingrained in and promoted by economists today. Lionel Robbins’s proposition that “Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses” is the dominant definition of economics. It implicitly emphasizes the importance of specialization, so that those “scarce means which have alternative uses” can be efficiently allocated to achieve the maximum level of output.

This belief in the advantages of specialization lies behind the incredulity with which economists have reacted to the rise of populist politicians like Donald Trump in the United States, as well as the United Kingdom’s vote for Brexit. They have, at their most self-righteous, blamed the rise of anti-globalization sentiment on the public’s irrational failure to appreciate the net benefits of trade. Or, more commonly, they have conceded that perhaps the electorate has reacted negatively because the gains from trade have not been shared fairly. There is, however, another explanation for why anti–free trade sentiment has risen: the gains from specialization at the national level were not there to share in the first place, for sound empirical reasons that were ignored in Ricardo’s example. That ignorance has been ingrained in economics since then, as Robbins’s definition—dominant and superficially persuasive, but fundamentally limited—gave economists a starting point from which they could not properly perceive either the advantages or the costs of globalization.

Conservatism can mean: hold on to what you hold dear. Like nature. Like civility.

• Utilitarian Economics and the Corruption of Conservatism (Philip Pilkington)

The Oxford English Dictionary has two definitions of the word “conservatism.” The first defines it as a “commitment to traditional values and ideas with opposition to change or innovation”; the second defines it as “the holding of political views that favor free enterprise, private ownership, and socially conservative ideas.” The former definition strikes me as the classical definition; the latter, a more modern invention—as those who supported private ownership and free enterprise, such as John Locke and Adam Smith, were in their own times thought of as progressive liberals. But is there a conflict between the two? Not inherently. With the absolute monarchies either abolished or subordinated to the will of parliaments, private ownership and free enterprise have evolved into the status quo.

Given this, one can see how someone who defends this state of affairs might see him or herself as conservative. But in defending this status quo, many who think themselves conservative have instead slipped into supporting a truly radical social doctrine—namely, utilitarianism—a doctrine that has subsequently morphed into neoclassical or marginalist economics. This is a social doctrine that has very little concern for traditional values. Indeed, it often appears to be entirely nihilistic in its consideration of value and truth. Because utilitarianism in its modern form—neoclassical or marginalist economics—is often the primary doctrine used to defend private property and free enterprise, the two definitions from the Oxford dictionary mentioned earlier begin to clash with one another.

What is the essence of the utilitarian doctrine? At its heart, it is the conversion of the human being in all of his or her richness into simplistic, self-contained atoms that are motivated only by their reaction to pleasure and pain. The individual is viewed as a creature isolated from any community: All considerations of intersubjective dynamics are subordinated to atomistic subjective dynamics. Anything resembling intersubjectivity is, in the utilitarian doctrine, merely a product of atomistic desires. There is, as Margaret Thatcher once said, no such thing as society. Simultaneously, although the individual is stripped of all faculties but the ability to feel pleasure and pain, he or she is invested with the ability to perfectly calculate how to best maximize pleasure and minimize pain. Man is divested of his all-too-human nature and endowed with the extremes of animal desires and godlike, calculating omniscience.

Famous last words. Hey, if your paycheck depends on it… But sure, major transformation coming. Just not that one.

• ‘The Housing Industry Is In A Time Of Major Transformation’ (AFR)

Australia’s rising house prices reflect strong fundamentals, says Olumide Soroye, managing director of property data giant Corelogic’s US Information Solutions. Like Australia, which is experiencing rising house prices – which have doubled since the end of the global financial crisis – the US’s affordability is also worsening, Mr Soroye, who visited Australia and New Zealand last week, said. While the proportion of first-home buyers is higher in the US – 35% of total buyers compared with about 8 to 9% in Sydney and Melbourne – people trying to get into the housing markets for the first time are constrained in the US. Five years ago, first-home buyers were 50% of the US market. “The housing industry is in a time of major transformation and one of the forces at work that is going to drive that transformation is the affordability question,” Mr Soroye said.

“It exists here in the US and in Australia and New Zealand.” “Our view is the value of property since the GFC…the levels in the US while they are high they are still within range. We don’t think there is a systemic overvaluation.” “The question is, how does the system respond?” Mr Soroye said the use of macro-prudential tools – controlling lending to homebuyers – to cool the housing market was prudent and the US had done the same especially after the GFC. But that was not enough to reduce prices, and the key solution was supply, Mr Soroye said. He suggested government intervention, home design and the release of more suburban greenfield land supported by strong infrastructure. Reductions in stamp duty and assisted household funding could also help ease the affordability problem, Mr Soroye said.

Dispersing demand into the outer suburbs was another solution but it should be supported by fast trains and good roads. The pace of delivery of infrastructure must also be fast and timely. Importantly, the change in the designs of homes was crucial. Mr Soroye said in the US builders were starting to construct “multi-generational homes” to accommodate parents and their grown children on different floors. “In the context of the US, in 10 years 20% will be over 65. These are the type of parents who will have their millennial children come into their homes,” he said. “Millennials are over two thirds of first-home buyers so you need to figure out what to do with them.” And while planning was slow, particularly in NSW, Australia’s supply delivery was still better than the US and even the UK, Mr Soroye said.

Sometimes it’s too obvious that people are just making stuff up.

• Hard Brexit ‘Offers £135 Billion Annual Boost’ To UK Economy (BBC)

Removing all trade tariffs and barriers would help generate an annual £135bn uplift to the UK economy, according to a group of pro-Brexit economists. A hard Brexit is “economically much superior to soft” argues Prof Patrick Minford, lead author of a report from Economists for Free Trade. He says eliminating tariffs, either within free trade deals or unilaterally, would deliver huge gains. Campaigners against a hard Brexit said the plan amounts to “economic suicide”. The UK is part of the EU customs union, and so imposes tariffs – taxes on imports – on some goods coming into the country. Countries in the customs union don’t impose tariffs on each other’s goods, and every country inside the union levies the same tariffs on imports from abroad. So, for example, a 10% tariff is imposed on some cars imported from outside the customs union, while 7.5% is imposed on roasted coffee. Other goods have no tariffs.

The UK has said it is leaving the EU’s customs union because as a member it is unable to strike trade deals with other countries. Prof Minford’s full report, From Project Fear to Project Prosperity, is due to be published in the autumn. He argues that the UK could unilaterally – before a reciprocal deal is in place – eliminate trade barriers for both the EU and the rest of the world and reap trade gains worth £80bn a year. The report foresees a further £40bn a year boost from deregulating the economy, as well as other benefits resulting from Brexit-related policies. Prof Minford says that when it comes to trade the “ideal solution” would still be free trade deals with major economic blocks including the EU. But the threat that the UK could abolish all trade barriers unilaterally would act as “the club in the closet”.

The EU would then be under pressure to offer Britain a free trade deal, otherwise its producers would be competing in a UK market “flooded with less expensive goods from elsewhere”, his introduction says. He argues UK businesses and consumers would benefit from lower priced imported goods and the effects of increased competition, which would force firms to raise their productivity. [..] During the referendum campaign last year Prof Minford stoked controversy by suggesting that the effect of leaving the EU would be to “eliminate manufacturing, leaving mainly industries such as design, marketing and hi-tech”. However in a recent article in the Financial Times he suggested manufacturing would become more profitable post-Brexit.

Thinking in the right direction, but not quite there yet.

• Donald Trump Finally Comes Out of the Closet (Krieger)

The firing of Steve Bannon is in my opinion the most significant event to happen during the Trump administration thus far. Moreover, it will have massive reverberations across the U.S. political spectrum for years and years to come. I wasn’t planning on writing today, but this news is so incredibly significant I find myself with little choice. Taking a step back, part of the reason I was immediately able to see through the Trump con was due to my upbringing in New York City. The guy was constantly in the news my entire life, so I had a pretty decent understanding of where he was really coming from and what makes him tick. The mindset of your typical NYC-based billionaire real estate developer is filled with all sorts of perspectives and priorities, but thoughts of populism are not amongst them.

Trump used populism to get elected, and then as soon as he won, immediately appointed some of the most destructive oligarchs imaginable to run his administration. The reason I warned about this incessantly at the time, is because I learned the lesson from the Obama administration. People = policy, and the people Trump was elevating were almost unanimously awful. Irrespective of what you think of Bannon, him being out means Wall Street and the military-industrial complex is now 100% in control of the Trump administration. Prepare for an escalation of imperial war around the world and an expansion of brutal oligarchy. The removal of Bannon is the end of even a facade of populism. This is now the Goldman Sachs Presidency with a thin-skinned, unthinking authoritarian as a figurehead.

Meanwhile, guess who’s still there in addition to the Goldman executives? Weed obsessed, civil asset forfeiture supporting Jefferson Sessions. The Trump administration just became ten times more dangerous than it was before. With the coup successful, Trump no longer needs to be impeached. Here’s another prediction. Watch the corporate media start to lay off Trump a bit more going forward. Rather than hysterically demonize him for every little thing, corporate media will increasingly give him more of the benefit of the doubt. After all, a Presidency run by Goldman Sachs and generals is exactly what they like. Trump finally came out of the closet as the anti-populist oligarch he is, and the results won’t be pretty.

Corporate media got the scalp it wanted, so the hysterical criticisms of him will die down. This is not to say I think the media will become pro-Trump, it just means the obsessive and aggressive propaganda will be dialed back considerably. Trump is now inline, and he will be rewarded by the establishment for that. He will learn that the more he gets with the program, the easier his life will be and the more secure his power. He is merely being conditioned, and my forecast is that Trump will gladly embrace the worst parts of the establishment going forward. Why? Because Trump’s true worldview fits in way more with Goldman Sachs and the military-industrial complex than with populism. It always has. The whole thing was just an act to get elected. Firing Bannon is just Trump coming home to who he always was. A ruthless oligarch.

A clash that has nothing to do with Trump.

• The Coming Clash Of Empires (Gavekal)

History shows that maritime powers almost always have the upper hand in any clash; if only because moving goods by sea is cheaper, more efficient, easier to control, and often faster, than moving them by land. So there is little doubt that the US continues to have the advantage. Simple logic, suggests that goods should continue to be moved from Shanghai to Rotterdam by ship, rather than by rail. Unless, of course, a rising continental power wants to avoid the sea lanes controlled by its rival. Such a rival would have little choice but developing land routes; which of course is what China is doing. The fact that these land routes may not be as efficient as the US controlled sealanes is almost as irrelevant as the constant cost over-run of any major US defense projects. Both are necessary to achieve imperial status.

As British historian Cyril Northcote Parkinson highlighted in his mustread East And West, empires tend to expand naturally, not out of megalomania, but simple commercial interest: “The true explanation lies in the very nature of the trade route. Having gone to all expenses involved… the rule cannot be expected to leave the far terminus in the hands of another power.” And indeed, the power that controls the end points on the trading road, and the power that controls the road, is the power that makes the money. Clearly, this is what China is trying to achieve, but trying to do so without entering into open conflict with the United States; perhaps because China knows the poor track record of continental empires picking fights with the maritime power. Still, by focusing almost myopically on Russia, the US risks having its current massive head-start gradually eroded. And obvious signs of this erosion may occur in the coming years if and when the following happens:

• Saudi Arabia adopts the renminbi for oil payments • Germany changes its stripes and cozies up to Russia and pretty much gives up on the whole European integration charade in order to follow its own naked self-interest. The latter two events may, of course, not happen. Still, a few years ago, we would have dismissed such talk as not even worthy of the craziest of conspiracy theories. Today, however, we are a lot less sure. And our concern is that either of the above events could end up having a dramatic impact on a number of asset classes and portfolios. And the possible catalyst for these changes is China’s effort to create a renminbi-based gold market in Hong Kong. For while the key change to our global financial infrastructure (namely oil payments occurring in renminbi) has yet to fully arrive, the ability to transform renminbi into gold, without having to bring the currency back into China (assuming Hong Kong is not “really” part of China as it has its own supreme court and independent justice system… just about!) is a likely game-changer.

Clearly, China is erecting the financial architecture for the above to occur. This does not mean the initiative will be a success. China could easily be sitting on a dud. But still, we should give credit to Beijing’s policymakers for their sense of timing for has there ever been a better time to promote an alternative to the US dollar? If you are sitting in Russia, Qatar, Iran, or Venezuela and listening to the rhetoric coming out of Washington, would you feel that comfortable keeping your assets, and denominating your trade, in dollars? Or would you perhaps be looking for alternatives? This is what makes today’s US policy hard to understand. Just when China is starting to offer an alternative—an alternative that the US should be trying to bury—the US is moving to “weaponize” the dollar and pound other nations—even those as geo-strategically vital as Russia—for simple domestic political reasons. It all seems so short-sighted.