Jack Delano Freight operations on the Indiana Harbor Belt railroad 1943

“The resilient consumer”. Sure.

• US Q4 GDP Rose 1.4% As Corporate Profits Plunged (ZH)

While the final revision to Q4 2015 GDP was so irrelevant it was released on a holiday when every US-based market is closed, even the futures, it is nonetheless notable that according to the BEA in the final quarter of 2015 US GDP grew 1.4%, up from the 1.0% previously reported, and higher than the 1.0% consensus estimate matching the highest Q4 GDP forecast. The final Q4 GDP print was still well below the 2.0% annualized GDP growth reported in Q3.

The figure marks a slowdown from the 2.2% average pace in the first three quarters of 2015. For all of last year, the U.S. economy grew 2.4% matching the advance in 2014. The reason for the change was largely due to upwardly Personal Consumer Spending, which rose from a contribution of 1.38% to the annualized bottom line to 1.66%. In CAGR terms, personal consumption rose 2.4%, following the 3.0% increase in Q3, higher than the 2.0% previously estimated.

Stripping out inventories and trade, the two most volatile components of GDP, so-called final sales to domestic purchasers increased at a 1.7% rate, compared with a previously estimated 1.4% pace. The rest of the GDP components were largely unchanged, with Fixed Investment adding 0.06% to the bottom line, up from 0.02% in the previous estimate, Private Inventories contracting fractionally more than previously estimated (-0.22% vs -0.14%), net trade subtracting 0.1% less from growth (-0.14% vs -0.25%), and finally government spending largely unchanged and hugging the unchanged line at 0.02%.

But while the “resilient consumer” once again carried the US economy in the fourth quarter, largely due to an estimated jump in spending on Transportation and Recreational services, which added an annualized $13 billion to the US economy vs the prior estimate, more disturbing was the drop in profits which we already knew courtesy of company reports and is known confirmed by the BEA whose GDP report also showed that corporate profits dropped in 2015 by the most in seven years. As Bloomberg writes, the earnings slump illustrates the limits of an economy struggling to gather steam at the start of this year. Some companies, encumbered by low commodities prices and sluggish foreign markets, are cutting back on investment while a firm labor market and low inflation encourage households to keep shopping.

Pre-tax earnings declined 7.8%, the most since the first quarter of 2011, after a 1.6% decrease in the previous three months. The estimate of nonfinancial corporate profits was reduced by a $20.8 billion settlement, considered a transfer to the government, between BP and the U.S. after the 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Profits in the U.S. dropped 3.1% in 2015, the most since 2008. Corporate earnings are being weighed down by weak productivity, rising labor costs and the plunge in energy prices. Economists at JPMorgan had expected a 9.5% drop in pre-tax earnings in the fourth quarter. “The pace of growth slowed as we ended 2015, though consumer spending is still the primary underpinning of this economic expansion,” Sam Bullard at Wells Fargo in Charlotte, North Carolina, said before the report. “Any pickup we might see is still likely going to be capped given the overall global picture.”

Globalization is ending.

• World Trade Collapses in Dollars, Languishes in Volume (WS)

The Merchandise World Trade Monitor by the CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, a division of the Ministry of Economic Affairs, tracks global imports and exports in two measures: by volume and by unit price in US dollars. And the just released data for January was a doozie beneath the lackluster surface. The World Trade Monitor for January, as measured in seasonally adjusted volume, declined 0.4% from December and was up a measly 1.1% from January a year ago. While the sub-index for import volumes rose 3% from a year ago, export volumes fell 0.7%. This sort of “growth,” languishing between slightly negative and slightly positive has been the rule last year. The report added this about trade momentum:

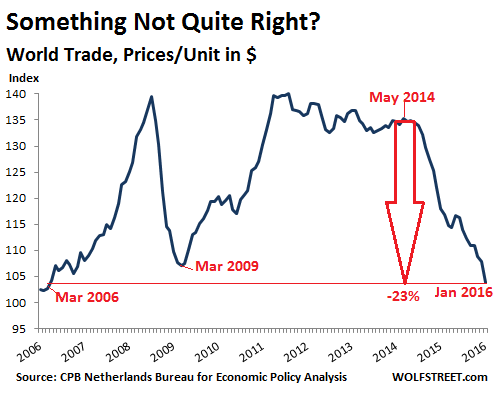

“Regional outcomes were mixed. Both import and export momentum became more negative in the United States. Both became more positive in the Euro Area. Import momentum in emerging Asia rose further, whereas export momentum in emerging Asia has been negative for four consecutive months.” This is also what the world’s largest container carrier, Maersk Lines, and others forecast for 2016: a growth rate of about zero to 1% in terms of volume. So not exactly an endorsement of a booming global economy. But here’s the doozie: In terms of prices per unit expressed in US dollars, world trade dropped 3.8% in January from December and is down 12.1% from January a year ago, continuing a rout that started in June 2014. Not that the index was all that strong at the time, after having cascaded lower from its peak in May 2011.

If June 2014 sounds familiar as a recent high point, it’s because a lot of indices started heading south after that, including the price of oil, revenues of S&P 500 companies, total business revenues in the US…. That’s when the Fed was in the middle of tapering QE out of existence and folks realized that it would be gone soon. That’s when the dollar began to strengthen against other key currencies. Shortly after that, inventories of all kinds in the US began to bloat. Starting from that propitious month, the unit price index of world trade has plunged 23%. It’s now lower than it had been at the trough of the Financial Crisis. It hit the lowest level since March 2006:

This chart puts in perspective what Nils Andersen, the CEO of Danish conglomerate AP Møller-Maersk, which owns Maersk Lines, had said last month in an interview following the company’s dreary earnings report and guidance: “It is worse than in 2008.” But why the difference between the stagnation scenario in world trade in terms of volume and the total collapse of the index that measures world trade in unit prices in US dollars? The volume measure is a reflection of a languishing global economy. It says that global trade may be sick, but it’s not collapsing. It’s worse than it was in 2011. This sort of thing was never part of the rosy scenario. But now it’s here.

‘Explaining’ what they don’t understand themselves.

• Bank of Japan’s Latest PR Move: ‘Negative Rates in Five Minutes’ (WSJ)

The Bank of Japan launched a charm offensive Friday to win over spooked members of the public who have reacted negatively to negative interest rates. The central bank issued a booklet offering a crash course in the basic implications of negative rates, a move that demonstrates the strength of unease created by the introduction of a policy in a nation largely unfamiliar with the concept behind it. Written in a question-and-answer format and in a somewhat casual Japanese, the three-page booklet aims to explain negative rates “in five minutes” by covering 18 issues that have grabbed public attention. Negative rates have become a political hot potato ahead of July’s national elections, with opposition lawmakers accusing the central bank of creating anxiety among consumers. Some ruling party politicians, perhaps feeling uncomfortable about the prospect of explaining the policy to their constituents, are also feeling the jitters.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe acknowledged Thursday that negative rates have made households nervous and it will likely take some time before people understand them. The Bank of Japan decided to start charging interest on some deposits held by commercial banks at the central bank in January. The policy is part of broader efforts to defeat deflation and create a stronger economy, but the central bank was ill-prepared for the public backlash the policy generated. One of the most common concerns over the policy is whether individuals with regular bank accounts will be charged interest on their deposits at the commercial banks. Opposition lawmakers have frequently quizzed BOJ Gov. Haruhiko Kuroda on this issue in parliament.

“Although the measure is called negative rates, it only involves imposing negative rates on a part of the money deposited at the BOJ by banks,” the booklet says. “Individuals’ deposits are different.” While addressing concerns over the new policy, the central bank also tries to convey the message that Japan must get rid of deflation, a negative cycle of price falls, adding that it has taken the right steps to do just that. “If prices don’t rise because of deflation, this means companies’ revenues don’t increase, and that’s why salaries don’t rise,” the booklet says. Since company earnings have improved a lot during the past three years of monetary easing, firms have started increasing basic pay, it says, adding that salaries will keep rising each year if deflation is overcome.

“..weakness means weak Japanese economy means sell Japanese assets.. and we will soon see capital controls in the world’s largest debtor nation…”

• Foreigners Dumped More Japanese Stocks This Week Than Ever Before (ZH)

USDJPY just had its best week in 2 months, funding bullish momentum and carry trades around the world in the midst of dismal economic data everywhere and tumbling earnings expectations. This "bullish" Yen strength, however, amid China's biggest weekly devaluation in almost 3 months, was ironically driven by drastic investment outflows – record sales of Japanese stocks by foreigners (sell JPY), and record purchases of foreign bonds by Japanese investors (sell JPY). Sooner, rather than later, it is obvious that the investment outflows will dominate the carry trades (see Thursday and Friday) and Kuroda and Abe will have a major problem.

Yen was dumped all week…

Which provided just enough juice for carry trades to lift Japanese stocks (despite the weakness in data and China's biggest weekly Yuan devaluation in almost 3 months)

But notice that the last two days have seen Japanese stocks decouple from USDJPY, perhaps the first glimpse of the investment outflows overwhelming any casino-based carry trades flows.

And this is why… Foreigners sold a record amount of Japanese stocks last week… (implicitly meansing Yen was sold)

And Japanese investors fled the insanity of record low yields in JGBs, buying a record amount of foreign bonds last week (implicitly selling Yen again)…

So the Yen weakness – which was so bullishly supportive of global equity markets via carry – was in fact a signal of massive investor anxiety fleeing the sinking ship. Peter Pan-ic indeed.

Abe and Kuroda will soon face a major problem as a weaker Yen will signal the exact opposite trade that has been so active since 2012 – weakness means weak Japanese economy means sell Japanese assets.. and we will soon see capital controls in the world's largest debtor nation.

And remember – the devaluation of The Yen has done nothing – NOTHING – to improve exports for Japan…

It’s all about the dollar.

• Yuan’s Fall Drags Down Chinese Companies (WSJ)

A weaker Chinese currency has roiled global markets and heightened worries about the state of the world’s second-largest economy. Now, some Chinese companies are reporting they’ve taken a hit from a depreciating yuan. The yuan fell 5% against the U.S. dollar in 2015, plunging after China’s central bank surprisingly devalued the currency in mid-August. A weaker currency helps the country’s exporters but hurts Chinese companies that pay for raw material in U.S. dollars or need to pay off loans in U.S. dollars. Among those negatively affected are firms that source from outside China, such as milk or food companies, as well as real estate companies that hold a lot of dollar-denominated debt, says Herald van der Linde at HSBC.

This was the case with Hengan International, one of the leading makers of tissue paper in China. The company said in a statement it saw $55.3 million in foreign-exchange losses in 2015 because it pays for raw material in U.S. dollars, holds U.S.-denominated debt and has Hong Kong-based yuan-denominated assets, which dropped in value. This contributed to a decline in tissue sales, it said. Weaker currencies also hurt China’s heavily-indebted real-estate developers. Shanghai-based property developer Shui On Land reported its 2015 profit dropped to 1.77 billion yuan ($272 million) from 2.49 billion yuan ($382 million) a year earlier in large part due to the depreciation of the company’s USD- and HKD-denominated debt. Then there are companies that suffer losses from selling to countries whose currencies have weakened.

Sourcing and logistics giant Li&Fung said 2015 revenue dropped 2.4% on year. The main reason? Foreign-exchange losses from weak European and Asian currencies, it said, since 38% of the company’s business is in non-U.S. markets but it accounts in U.S. dollars. In order to tackle the problem, some companies are looking to shed yuan — or at least get it out of the country. Hengan, the tissue company, has remitted the equivalent of several billion Hong Kong dollars from mainland China to Hong Kong in 2015, and another HK$2 billion in the first quarter of this year, said CFO Vincent Loo in Hong Kong. It is also negotiating with sources to pay them in less time — from 30 to 60 days rather than 90 — just in case the yuan continues to fall.

Beijing’s ‘vision’ is now limited to short term only.

• Shanghai Rolls Out Tightening Measures To Cool Home Market (Reuters)

Municipal authorities in Shanghai tightened mortgage down payment requirements for second home purchases on Friday, in a move to cool an overheating property market and reduce fears of a bubble. Senior Chinese leaders raised concerns about the country’s overheated housing market during an annual parliament meeting this month, and Shanghai is the biggest city to take action in the wake of the National People’s Congress, which ended a week ago. Under the new rules, home buyers will need to put down 50-70% of the price of a second home, compared to 40% previously, to qualify for a mortgage. “The new measure will have a big impact on market sentiment on both the primary and secondary market; new launches being sold out within one, two hours will not happen again,” said Joe Zhou, head of East China research at real estate services firm Jones Lang LaSalle.

With the new rules, Shanghai also made it harder for non-residents to buy homes in the city, according to a statement issued by the local government. Potential buyers who do not hold local residence permits, or hukou, must have paid social insurance or taxes in Shanghai for at least five years before they can purchase property. Previously the requirement was two years. Shanghai will also increase the supply of small- and medium-sized homes and crack down on property financing by informal financial institutions. Shanghai home prices gained 20.6% in February from a year ago, posting the second biggest gain in the country after the southern city of Shenzhen, where prices soared 56.9%, despite slowing economic growth.

A world full of housing bubbles. Haven’t we understood how dangerous that is?

• Affordable Housing Crisis Has Engulfed All Cities In Southern England (G.)

There is no longer a city in the south of England where house prices are less than seven and a half times average local incomes, according to analysis by Lloyds Bank that reveals how the home affordability crisis now stretches far beyond London. “The housing affordability gap has widened to its worst level in eight years,” said the Lloyds analysis, noting that the last time prices were so high was at the very top of the boom in 2008, just before the financial crisis struck. The Lloyds analysis is unique in that it compares local house prices with local earnings rather than national averages. On this measure, the worst house prices are not in London but in other parts of the south-east. Oxford is again identified as the least affordable city in the UK, with average prices at 10.68 times local earnings.

Winchester is a close second at 10.54, with London third at 10.06. Cambridge, Brighton and Bath all have prices that are now nearly 10 times local earnings, while cities such as Bristol and Southampton have prices close to eight times earnings. Wage growth has fallen far behind the rise in house prices, said Lloyds, with affordability worsening for the third successive year. The average home in a city in the UK now costs 6.6 times average local earnings, up from 6.2 last year. In the 1950s and 1960s, buyers could typically find homes with mortgages of three to four times their income. But the Lloyds figures show that there is now just one city in the UK that fits that profile: Derry in Northern Ireland. House prices in the city currently fetch 3.81 times local incomes.

While most of the “most affordable” cities in the Lloyds rankings are in the north, Scotland and Northern Ireland, buyers will still be stretched to afford a home from the local salaries on offer. Hull is widely regarded as a low house price area, yet local residents face having to pay 5.11 times average local incomes to buy a home. Meanwhile, York has joined the ranks of cities in the south in the unaffordability tables, with prices at 7.5 times incomes.

When crazy ‘conventional’ ideas fail…

• Radical Economic Ideas Grab Attention Amid Low-inflation Torpor (SMH)

Our economic guardians at Federal Treasury and the Reserve Bank sound increasingly uneasy about some policy choices being made offshore. Since the global financial crisis, quantitative easing has pumped trillions of dollars into major economies with limited success. More recently central banks in Europe and Japan have opted for negative interest rates in a bid to kick-start growth. On Tuesday the Treasury Secretary, John Fraser, pointed out that we’ve now been in an “experimental stage” with monetary policy for more than seven years. “A range of different interventions have been tried with, at least to date, mixed results,” he said. “Sadly, we will have to await the passage of years before we can pass final judgment.” What is clear, warned Fraser, is that these unusual policies “have had a pervasive and frankly quite worrying impact on the pricing of financial risk.”

Earlier this month the Reserve’s deputy governor, Philip Lowe, said it was “very rare” for central banks to worry that inflation is too low. “Yet today, we hear this concern quite often, and the ‘unconventional’ has almost become conventional,” he said. Lowe warned the abnormal monetary policies being adopted in some countries were “a complication for us” because they put upward pressure on exchange rate. But in a world where traditional economic remedies are proving ineffective a swag of other unorthodox policy suggestions are getting a hearing. One controversial option being canvassed by experts is for central banks to deliver “helicopter drops” of cash directly to citizens’ bank accounts in the hope they will spend it and revive growth. Even more radical is a proposal for governments to mandate an across-the-board pay rise for workers.

Olivier Blanchard, a former chief economist at the IMF, and Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, recently recommended the Japanese government try this approach to boost growth. The Bank of England’s chief economist, Andy Haldane, raised eyebrows last September when he argued abandoning cash altogether would make it easier for central banks to manage downturns. He warned that in future it might be necessary for central banks to opt for negative interest rates when depositors are charged for putting their money in the bank in a bid to encourage spending. One problem with that strategy, however, is that people are likely to convert deposits into cash. Eliminating cash and replacing it with a government-backed digital currency would remove that option. “This would preserve the social convention of a state-issued unit of account and medium of exchange… But it would allow negative interest rates to be levied on currency easily and speedily,” Haldane said.

A second part from the article above.

• Modern Monetary Theory Has Ardent Proponents (SMH)

As central banks struggle to revive growth, attention has shifted to fiscal policy the way governments use taxation and spending to influence the economy. Even the hard-heads at the IM have advised governments, including Australia’s, to spend more especially on infrastructure. The fund’s most recent assessment of our economy said “raising public investment (financed by borrowing, thus reducing the pace of deficit reduction) would support aggregate demand, take pressure off monetary policy, and insure against downside growth risks.” Amid these debates about fiscal policy, a radical school of thought called Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT, has gained more prominence. Proponents of this theory have been on the periphery of mainstream economics for more than two decades but their profile has been raised by this year’s US presidential race.

Academic economist Stephanie Kelton , a leading advocate of MMT, is an adviser to presidential hopeful, Senator Bernie Sanders. Kelton calls herself a deficit “owl” rather than a deficit hawk or dove. The hawks, of course, have a straightforward view of government finances: deficits are bad. The doves say deficits are necessary when economic times are tough but they should be balanced by surpluses over time. But deficit owls like Kelton have a far more radical take: deficits don’t matter. The starting point for Modern Monetary Theory is that a currency issuing government can keep printing and spending money but never go broke, so long as it doesn’t borrow in a foreign currency. The Australian Commonwealth, for example, will never run out of Australian dollars because it is a monopoly issuer of that currency.

It can always create the money it needs and, therefore, will always be able to service debts. The MMTers claim that in the modern era of floating exchange rates and deregulated financial markets, governments can, and should, run deficits whenever they are needed. There is a strong moral case for this: in a modern economy, there’s no good reason to have unemployed labour or capital. For the MMTers mass unemployment is a great evil and its daily, human cost dwarfs other economic challenges. They acknowledge there are limits to government spending. Resources in the real economy can be constrained and taxes are an essential tool to ensure demand for the currency and to cool the economy if it overheats. But there’s plenty of scope for governments to print and spend money without causing inflation or triggering a financial crisis. MMTers say sophisticated modern economies like the US and Australia are in no danger of the hyper-inflation which plagued Zimbabwe last decade or Germany’s Weimar Republic in the 1930s.

Barely functioning, politically nor economically.

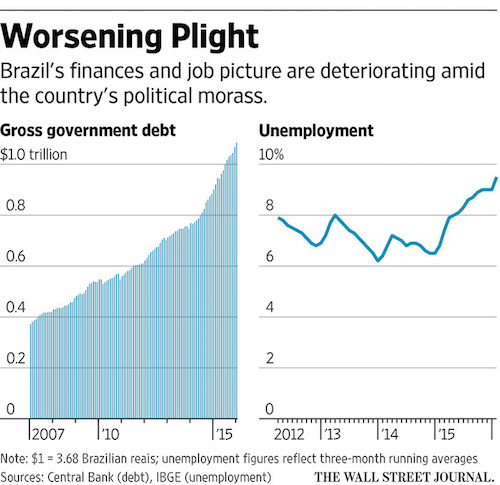

• Brazil Economic Woes Deepen Amid Political Crisis (WSJ)

Brazil’s economic crisis is as bad as its political one. Latin America’s biggest economy appears headed for one of its worst recessions ever. It stalled in 2014, shrank 3.8% last year and now faces a similar contraction this year. Unemployment rose to 9.5% on Thursday as wages fell 2.4%, both trends forecast to worsen. One in five young Brazilians is out of work, and Goldman Sachs says Brazil may be facing a depression. The deteriorating outlook forms a dire backdrop for Brazil’s political straits. President Dilma Rousseff, deeply unpopular, faces impeachment proceedings in Congress amid a widening corruption scandal surrounding the state oil company, Petróbras. That situation is consuming so much energy from policy makers and Congress that the economic downturn isn’t getting the attention it needs, observers say.

“The gravity of the situation is this: We have the kind of problems where if nothing is done, things will definitely get worse,” said Marcos Lisboa, a former finance ministry official who is now president of the Insper business school in São Paulo. “Pretty soon we could be talking about the solvency of the federal government.” Brazil fended off the results of the 2008 global downturn with stimulus spending, and is trying to again inject money into the economy to spur demand. In January, the Rousseff administration unveiled some $20 billion of subsidized loans from state-owned banks such as the BNDES to boost agriculture and builders of big infrastructure projects.

But this time, the country has less leeway to fund stimulus measures. Brazil’s tax take is diminishing, and the Planning Ministry said Tuesday the government needs to cut around $5.9 billion of spending to meet its budget target. On Thursday, Finance Minister Nelson Barbosa asked Congress to loosen the target to allow a bigger deficit in 2016. Some investors say stimulus policies such as cheap credits from state banks haven’t done much long-term good, because they produced big deficits and the money was often poorly invested in money-losing dams and refineries.

“..very few people understood that an epochal change had taken place in the American economy. GDP would grow. Income wouldn’t.”

• The River: America’s 40-Year Hurt (BBC)

Bruce Springsteen is coming to London with the River tour. At £170 for the cheapest pair, I can’t afford to see the Boss any more, even if my body could handle standing on Wembley Stadium’s pitch for three-and-a-half-hours in an early June drizzle. It’s interesting that Springsteen is re-exploring The River album again. Whenever the anger that simmers in America erupts and reminds the rest of the world that the country is troubled, he seems to be the cultural figure whose work offers an explanation. In late 1986, midway through Ronald Reagan’s second term of office, with the twin scourges of Aids and crack racing through American cities and New Deal ideas of economic and social fairness consumed by the Bonfire of the Vanities taking place on Wall Street, Britain’s Guardian newspaper ran an editorial that said, “for good or ill, [America] is becoming a much more foreign land”.

I had just celebrated my first anniversary as an ex-pat in London and wrote an essay trying to explain what America was like away from the places Guardian readers knew. I described the massive population dislocations that followed the long recession that had begun in the mid-70s. I referenced Springsteen. The piece ran under the headline “Torn in the USA”. Now America is going through even worse ructions. But there is nothing fundamentally new. What we are seeing is the continuation of a disintegration that began forty years ago around the time Springsteen was writing the title song of the album. The River, which came out in 1980, was very much about guys trying to kick back at father time and stave off the inevitable arrival of life’s responsibilities – wife, kids, job, mortgage – and the equally probable onset of life’s disappointments in wife, kids, job, mortgage, and in oneself.

The title track is a long, mournful story about that process and the narrator’s desire to reconnect to the person he was when younger and full of hope. “I come from down in the valley / Where mister, when you’re young / They bring you up to do/like your daddy done…” The key point is being brought up to be like your father. Work the same job, carry yourself in the same way, do the right thing. In the song this tie that binds is seen as restricting the choices you can make in life. Your daddy worked in a steel mill, you will work in a steel mill, or on the line at River Rouge, or down a mine. Today, what wouldn’t many of us give for the economic and social stability that gave resonance to Springsteen’s lyrics? A union job, 30 years of work, a pension. Sounds sweet. The narrator of the song goes on to tell us, “I got a job working construction at the Johnstown company / but lately there ain’t been much work on account of the economy.”

Springsteen based the song on the struggle of his brother-in-law to stay employed during the bleak days after the Oil Shock of 1973: a half-decade of inflation and economic stagnation. At the time this stagflation was seen as a cyclical event, the economy would rebound soon. It would be boom time for all. The economy did rebound, but then went into recession in 1982, and rebounded and went into recession at regular intervals, until the near-death experience of 2007/2008. But very few people understood that an epochal change had taken place in the American economy. GDP would grow. Income wouldn’t. Median salaried workers’ wages stagnated. Those working low-wage jobs saw their incomes decline. As for job security, a perfect storm of automation, declining union power, and free-trade agreements put an end to that.

All the time I’m thinking someone must stand up and say ‘till here and no further’. But instead, Europe tumbles to new lows on a daily basis.

• Hope Turns To Despair As Lesbos Camp Becomes Open-Air Prison (Ind.)

Even before it became a holding pen, Moria was a pretty poor registration centre, unable to provide basic facilities and painfully slow to process the thousands of refugees and migrants who arrive on the shores of Lesbos every week. But since midnight on Sunday, when the new EU-Turkey migrant deal came into force, refugees have been picked up by the coastguard and transported directly to Moria by the Greek authorities. The camp has become an open-air prison, a compound of temporary buildings on a hill overlooking the coast of this island, not far from Turkey’s Mediterranean coast. It is to here that all arrivals must wait for the news their long struggle to reach Europe will almost certainly get them no further than the Greek islands.

They will be returned to Turkey, which the EU has now declared a safe country, in its bid to stem the biggest refugee crisis since the Second World War. The lightning fast implementation of the deal, signed last Friday, has stretched to the limit the capacity of the Greek government, which has no means to process the asylum claims that everyone who arrives has the right to make. Those who came looking for peace and a better life have instead found themselves locked up, and handed detention papers. In response, aid agencies have dropped out of their involvement at the centre one by one, refusing to be associated with the detention of migrants – among whom are more than 100 unaccompanied children. Oxfam this week said the development was “an offence” to Europe’s values.

“They have told us nothing,” says Naima Abdullah, 28, speaking through the chain link fence, her four-year-old daughter Mirna by her side. She paid $2,000 for herself, Mirna, and her one-month-old baby to cross the sea from Turkey after fleeing air strikes in rural Damascus three months ago. She arrived on Sunday, in the first boats after the deal came into force. But four days later, she still hadn’t been given an opportunity to register a claim for asylum. And as the numbers grow, observers worry the only possible outcome will be the mass expulsions Europe has promised to avoid. Nadine Abuasil, 25, said she came to Lesbos because life in Turkey since she fled Deraa in Syria a month ago was not worth living. Her family were blackmailed for money by local gangs, and there was no work in a country that is expensive to live in. “We cannot go back to Turkey,” she says simply.

She and her 23-year-old brother arrived on Sunday after a five hour boat journey during which two men died. They had apparently suffocated. She points to the ground of the detention centre. “We would rather die here than in Turkey.” Her brother, Mohammed, was no less emphatic when asked what he’d do if he was forced to return. “I don’t speak English,” he says. “But: kill myself, kill myself.” The deal has been decried by human rights groups and legal experts who question if Turkey can be considered a safe third country for the forcible return of migrants, and if Greece, which has floundered under the pressure of more than one million refugees arrivals in the past year, is capable of processing asylum claims – even with promised outside help.

“Greece has effectively been asked to build an asylum system in two weeks,” says Camino Mortera, a research fellow for the Centre for European Reform and a specialist in EU law. “The EU claims there won’t be returns en masse but if you are not able to process people in a regulated fashion, how else are they going to deal with this?”

Home › Forums › Debt Rattle March 26 2016