Harris&Ewing State, War & Navy Building, Washington DC 1917

Absolutely must see Farage video.

• Those In Power Will Risk War And Civil Unrest To Preserve It (Martin Armstrong)

Nigel Farage may be the only practical politician these days because he came from the trading sector. He explains the Euro-Project and its failures. He makes it clear that the Greek people never voted to enter the euro, and explains that it was forced upon them by Goldman Sachs and their politicians. Nigel also explains that the Euro project idea that a trade and economic union would then magically produce a political union – the United States of Europe and eliminate war. He has warned that the idea of a political union would end European wars has actually turned Europe into a rising resentment in where there is now a new Berlin Wall emerging between Northern and Southern Europe.

The Euro project was a delusional dream for it was never designed to succeed but to cut corners all in hope of creating the United States of Europe to challenge the USA and dethrone the dollar, That dream has turned into a nightmare and will never raise Europe to that lofty goal of the financial capitol of the world. The IMF acts as a member of the Troika, yet has no elected position whatsoever. The second unelected member is Mario Draghai of the ECB. Then the head of Europe is also unelected by the people. The entire government design is totally un-Democratic and therein lies the crisis.

Not a single member of the Troika ever needs to worry about polls since they do not have to worry about elections. This is authoritarian government if we have ever seen one. The ECB attempts by sheer force to manipulate the economy with zero chance of success employing negative interest rates and defending banks as the (former?) Goldman Sachs man Mario Draghai dictates. Now, far too many political jobs have been created in Brussels. This is no longer about what is best for Europe, it is what is necessary to retain government jobs. The Invisible Hand of Adam Smith works even in this instance – those in power are only interested in their self-interest and will risk war and civil unrest to maintain their failed dreams of power.

If true, a main argument for Greece.

• Irish €14.3 Billion Payments To Bank Bondholders May Have Been Avoidable (TFM)

The legal advisor to the former government has said it WOULD have been legally possible to burn the bondholders of Ireland’s banks, without customers having to lose their deposits. The advice from the former attorney general Paul Gallagher appears to contradict the claims of some former ministers. Ministers in the former administration have consistently claimed that it would have been impossible to ‘burn’ bondholders without also enforcing a haircut on deposits, because the two were considered legally equal. However today Mr Gallagher has said that although it would have been difficult, it was legally possible to break this link and enforce losses on bondholders without depositors also taking a hit.

He said this had also been accepted by the Troika – but that the lenders simply refused to allow any burden-sharing under the bailout programme, making the prospect obsolete. Unsecured senior bondholders were paid around €14.3 billion under the period of the bank guarantee – much of it as a result of the state’s huge investment in the banking sector. Mr Gallagher’s evidence seems to suggest that these payments could have been avoided without depositors also facing any losses, but for the Troika’s stance.

If Argentina can do it…

• Why Argentina Consistently, and Unapologetically, Refuses to Pay Its Debts (BBG)

Argentina’s fight with foreign banks and bondholders is more than just business. It’s part of the national psyche, enshrined in a special museum at the business school at the University of Buenos Aires. The Museum of Foreign Debt is nothing fancy. There are a few flimsy panels plastered with grainy photos, dates, text, and graphs. Oh, but the saga portrayed on those panels! Banks, bond investors, and the International Monetary Fund flood crooked regimes with overpriced credit. The Argentine economy collapses, and the people suffer. International markets are roiled. It happens time and time again. The story has all the emotions of a good tango. Argentina has reneged on foreign debt obligations at least seven times, starting in 1827.

The latest was in July 2014, when Argentina defaulted rather than give in to pressure from Paul Singer of Elliott Management. The fight with Singer has been going on for a dozen years, and the term vulture investor—rather esoteric in much of the world—is now pretty much universally known in Argentina. It’s so much on people’s minds that Buenos Aires toy stores carry a homegrown board game called Vultures, packaged in a box depicting a pair of the birds picking at a pile of dollars. “We planted the anti-vulture flag in the world,” President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner said in a speech in mid-May. “We gave a name to international usury and despotism.” One May morning at the debt museum, guide Antonella Fagnano, a 21-year-old business major, describes Argentines’ attitude toward default.

She pauses by a black-and-white photo of the late General Jorge Videla, who led a 1976 coup that ushered in a seven-year dictatorship. Successive presidents in that period loaded up on foreign debt to finance, among other things, the 1982 Falklands War with the U.K. Today’s Argentina, Fagnano says, has no moral obligation to make good on debts like those. In fact, it would be wrong to pay. “Foreigners financed a lot of leaders, like these dictators. They didn’t do what they were supposed to do with the money, and left future generations the debt,” she says, shaking her head. “So, of course, you cannot allow that.” Fernandez is nearing the end of her term, and it doesn’t look like things will change under the next president. Daniel Scioli, the front-runner for October elections, vows to carry on the fight against paying the vultures in full.

And counting.

• China Unleashes $483 Billion to Stem the Market Rout (Bloomberg)

China has created what amounts to a state-run margin trader with $483 billion of firepower, its latest effort to end a stock-market rout that threatens to drag down economic growth and erode confidence in President Xi Jinping’s government. China Securities Finance Corp. can access as much as 3 trillion yuan of borrowed funds from sources including the central bank and commercial lenders, according to people familiar with the matter. The money may be used to buy shares and provide liquidity to brokerages, the people said, asking not to be named because the information wasn’t public. While it’s unclear how much CSF will ultimately deploy into China’s $6.6 trillion equity market, the financing is up to 25 times bigger than the support fund started by Chinese brokerages earlier this month.

That’s probably enough to restore confidence among China’s 90 million individual investors, says Bocom International Holdings Co. The Shanghai Composite Index jumped 3.5 % on Friday, capping a two-week rally that’s turned it into one of the world’s best-performing equity gauges. “It doesn’t have to use up all the money, as long as it can make the rest of the market believe that it has enough ammunition,” said Hao Hong, a China strategist at Bocom International in Hong Kong. “It is a game of chicken. For now, it seems to be working.” CSF, founded in 2011 to provide funding to the margin-trading businesses of Chinese brokerages, has transformed into one of the key government vehicles to combat a 32 % selloff in the Shanghai Composite from mid-June through July 8.

At 3 trillion yuan, its funding would be about five times bigger than the new proposed bailout for Greece and exceed China’s 2.3 trillion yuan of regulated margin financing during the height of the stock-market boom last month. “What the authorities are demonstrating to the market is that if panic does take hold, they have the resources at their disposal to deal with that,” said James Laurenceson, the deputy director of the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology in Sydney. “Monetary authorities around the word regularly send the same signal in credit and foreign exchange markets.”

“Chinese punters were borrowing in large sums, from both brokerages and more shadowy sources — like “umbrella trusts” and peer-to-peer lending websites — to buy shares, with the shares themselves as collateral.”

• China Destroyed Its Stock Market In Order To Save It (Patrick Chovanec)

During the Vietnam War, surveying the shelled wreckage of Ben Tre, an American officer famously remarked, “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.” His comment came to epitomize the sort of self-defeating “victory” that undoes what it aims to achieve. Last week, China destroyed its stock market in order to save it. Faced with a crash in share prices from a bubble of its own making, the Chinese government intervened ruthlessly, and recklessly, to turn those prices around. Its heavy-handed approach seemed to work, for the moment, but only by severely damaging far more important goals and ambitions. Prior to the crash, China’s stock market had enjoyed a blissful disconnect from reality. As China’s economy slowed and corporate profits declined, share prices soared, nearly tripling in just 12 months.

By the peak, half the companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges were priced above a preposterous 85-times earnings. It was a clear warning flag — one that Chinese regulators encouraged people to ignore. Then reality caught up. At first, when prices began to fall, the central bank responded by cutting interest rates and bank reserve requirements — measures to inject more money that had never failed to juice the market. But prices continued to fall. Then the government rallied the major brokerages to form a $19 billion fund to buy shares and waded directly into the market to buy stocks too. A few stocks rose, but most fell even further. The relentless crash was intensified by a new factor in Chinese markets: margin lending.

Chinese punters were borrowing in large sums, from both brokerages and more shadowy sources — like “umbrella trusts” and peer-to-peer lending websites — to buy shares, with the shares themselves as collateral. At the peak, according to Goldman Sachs, formal margin lending alone accounted for 12% of the market float and 3.5% of China’s GDP, “easily the highest in the history of global equity markets.” Margin loans served as rocket fuel for the market on its way up, but prices began to fall and borrowers received “margin calls” that forced them to liquidate their positions, pushing prices down further in a kind of death spiral.

Chinese regulators, who had been trying (ineffectually) to rein in risky margin lending, now suddenly reversed course. They waved rules requiring brokerages to ask for more collateral when stock prices fall and allowed them to accept any kind of asset — including people’s homes — as collateral for stock-buying loans. They also encouraged brokerages to securitize and sell their margin-lending portfolios to the public so that they could go out and make even more loans. All these steps knowingly exposed major financial institutions, and their customers, to much greater risk. Yet no one will borrow if no one is confident enough to buy, and the market continued to fall, wiping out nearly all its gains since the start of the year.

The deal “has an ownership problem for Tsipras and the Greeks in general..”

• Greece’s Tsipras Shakes Up Cabinet in Bid to Rebuild Government (Bloomberg)

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras replaced some ministers in a cabinet reshuffle after almost a quarter of his lawmakers rejected measures he agreed on with creditors to keep the country in the euro. The prime minister’s office said Friday that Panagiotis Skourletis will replace Panagiotis Lafazanis, who heads the Left Platform fraction of Tsipras’s Syriza party, as energy minister. George Katrougalos will succeed Panagiotis Skourletis as labor minister. The Greek parliament in the early hours of Thursday backed the deal with creditors, needed to unblock further financing aid, with decisive votes from the opposition. With 38 of 149 Syriza lawmakers refusing to support further spending cuts and tax increases, that marked a blow for Tsipras, who came to power on an anti-austerity platform in January.

Tsipras told his associates after the parliament vote that he would be forced to lead a minority government until a final deal with creditors is concluded. The European Union finalized a €7.2 billion bridge loan to Greece on Friday that will help provide the debt-ravaged nation with a stop-gap until its full three-year bailout is settled. In all, 64 of the parliament’s 300 lawmakers voted against the bill. Half of the “no” votes came from Syriza, including from Lafazanis and former Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis. Finance Minister Euclid Tsakalotos, called in by Tsipras to replace Varoufakis before the final bailout negotiations, discussed on Friday with Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel-prize winning economist, about the difficulties expected in the implementation of the deal with Greece’s creditors.

The deal “has an ownership problem for Tsipras and the Greeks in general,” said Paolo Manasse, a professor of economics at the University of Bologna, Italy. “It’s a liberal program to be carried out by a radical-left premier and imposed on a country that’s just voted no in a referendum.”

“To the Confidence Fairy we can now add the ‘Trust Troll’ : appease the Trust Troll, and all your macroeconomic ills will magically vanish.”

• Wolfgang Schäuble, The Trust Troll (Steve Keen)

Paul Krugman invented the term “confidence fairy” to characterize the belief that all that was needed for growth to resume after the Global Financial Crisis was to restore ‘confidence’. Impose austerity and the economy will not shrink, but will instead grow immediately, because of the boost to confidence:

.. don’t worry: spending cuts may hurt, but the confidence fairy will take away the pain. The idea that austerity measures could trigger stagnation is incorrect, declared Jean-Claude Trichet, the president of the European Central Bank, in a recent interview. Why? Because confidence-inspiring policies will foster and not hamper economic recovery. ( Myths of Austerity , July 1 2010)

To the Confidence Fairy we can now add the ‘Trust Troll’ : appease the Trust Troll, and all your macroeconomic ills will magically vanish. The identity of the Confidence Fairy was never revealed, but the identity of the Trust Troll is obvious. It‘s German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble. Schäuble was clearly the primary architect of the Troika’s dictat for Greece. One only has to compare its language to that used by Schäuble in his OpEd in the New York Times three months ago (Wolfgang Schäuble on German Priorities and Eurozone Myths , April 15 2015). There he stated that ‘My diagnosis of the crisis in Europe is that it was first and foremost a crisis of confidence, rooted in structural shortcomings , and that the essential factor in ending the crisis was the restoration of trust:

The cure is targeted reforms to rebuild trust in member states finances, in their economies and in the architecture of the European Union. Simply spending more public money would not have done the trick nor can it now.

Compare this to the first line of the communique:

The Eurogroup stresses the crucial need to rebuild trust with the Greek authorities as a pre requisite for a possible future agreement on a new ESM programme.

The policies in the document match those in Schäuble’s OpEd as well. Schäuble called for:

.. more flexible labor markets; lowering barriers to competition in services; more robust tax collection; and similar measures.

The Troika’s document forces these measures upon Greece. These include ‘the broadening of the tax base to increase revenue’, ‘rigorous reviews of collective bargaining, industrial action and collective dismissals’ and ‘ambitious product market reforms’. At the same time, Greece is required to aim to achieve a government surplus equivalent to 3.5% of GDP -the opposite of ‘spending more public money’ which Schäuble rejected in his OpEd. Rather than debt reduction and rescheduling as even the IMF now calls for, “The Euro Summit acknowledges the importance of ensuring that the Greek sovereign can clear its arrears to the IMF and to the Bank of Greece and honour its debt obligations”.

This cannot in any sense be seen as an economic document, since an economic document would have to assess the feasibility of its proposals. Instead it simply states Schäuble s ideology: regardless of your economic circumstances, simply implement these (so-called) market-oriented reforms, restore trust, and your economy will grow. With the government debt that Greece currently labours under, this is a fantasy. Even if Greece were to pay a mere 3% on its debt, interest payments alone would absorb over 5% of GDP. To do that, and run a primary surplus of 3.5% of GDP in an economy where 25% of the population is unemployed is simply impossible.

Karl Whelan makes much the same point as Steve Keen: “..the truth is it is really Grade-A concern trolling (“I’d love to help you guys but I can only do it if you leave the euro”) dressed up as legal argumentation.”

• Alice In Schäuble-Land: Where Rules Mean What Wolfgang Says They Mean (Whelan)

After trying his best to chuck Greece out of the euro last weekend, Germany’s finance minister Schäuble has continued to openly undermine the deal that was agreed by European leaders and endorsed by the Greek parliament. A key argument he has been putting forward is that a debt write-down for Greece “would be incompatible with the currency union’s rules” but that such a write-down would be possible if Greece left the euro. While this claim is being widely repeated in the German press, the truth is it is really Grade-A concern trolling (“I’d love to help you guys but I can only do it if you leave the euro”) dressed up as legal argumentation.

The rules of the EU and Eurozone are so byzantine that it is quite easy to make false claims about these rules and get away with it. However, I do not believe there is anything in the European Union or Eurozone rules that would preclude a debt write-down inside the euro. The basis for Schäuble’s argument appears to be Article 125.1 of the consolidated treaty on the functioning of the EU. Here is the article in full.

The Union shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of any Member State, without prejudice to mutual financial guarantees for the joint execution of a specific project. A Member State shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of another Member State, without prejudice to mutual financial guarantees for the joint execution of a specific project.

This is the article that used to be called “the no bailout clause”. However, it is nothing of the sort. It simply says that member states cannot take on the debts of another member state. This did not rule out member states “bailing out” other countries by making loans to them. And indeed, the European Court of Justice in its Pringle decision established that the European Stabilisation Mechanism bailout fund was consistent with Article 125. Also worth noting about Article 125 are all the things it doesn’t mention. It doesn’t rule out loans being member states and doesn’t discuss these loans being restructured. And it makes no mention whatsoever of the Eurozone. So there is simply no legal basis for the idea that Greek debt being written down is illegal while they remain in the Eurozone but is fine if they leave the euro.

It is conceivable that someone could still take a case to the ECJ objecting to a write-off on the grounds that the granting and write-off of loans to Greece would result in more debt for European countries and allowed Greece to pay off other creditors. So you could argue that this was effectively the same thing as the other member states assuming Greece’s other debt commitments. To my mind, this line of argumentation moves far away from the simple and clear language of Article 125.1. I also don’t see much in the Pringle decision to suggest the ECJ would uphold such a case. There would be even less case for a legal argument against an “effective write-off” involving postponing interest payments and principal payments for some very long period of time, such as 100 years.

So there is no “Eurozone rule” against a writing off Greek debt. Conversely, despite Schäuble’s enthusiastic support, the rules don’t allow for a euro exit. Rules it appears, mean whatever Mr. Schäuble wants them to mean.

“After all, Poland, the Czech Republic, Croatia, and Romania (not to mention Denmark and Sweden, or for that matter the United Kingdom) are still out and will likely remain so—yet no one thinks they will fail or drift to Putin because of that.”

• Greece, Europe, and the United States (James K. Galbraith)

SYRIZA was not some Greek fluke; it was a direct consequence of European policy failure. A coalition of ex-Communists, unionists, Greens, and college professors does not rise to power anywhere except in desperate times. That SYRIZA did rise, overshadowing the Greek Nazis in the Golden Dawn party, was, in its way, a democratic miracle. SYRIZA’s destruction will now lead to a reassessment, everywhere on the continent, of the “European project.” A progressive Europe—the Europe of sustainable growth and social cohesion—would be one thing. The gridlocked, reactionary, petty, and vicious Europe that actually exists is another. It cannot and should not last for very long.

What will become of Europe? Clearly the hopes of the pro-European, reformist left are now over. That will leave the future in the hands of the anti-European parties, including UKIP, the National Front in France, and Golden Dawn in Greece. These are ugly, racist, xenophobic groups; Golden Dawn has proposed concentration camps for immigrants in its platform. The only counter, now, is for progressive and democratic forces to regroup behind the banner of national democratic restoration. Which means that the left in Europe will also now swing against the euro.

As that happens, should the United States continue to support the euro, aligning ourselves with failed policies and crushed democratic protests? Or should we let it be known that we are indifferent about which countries are in or out? Surely the latter represents the sensible choice. After all, Poland, the Czech Republic, Croatia, and Romania (not to mention Denmark and Sweden, or for that matter the United Kingdom) are still out and will likely remain so—yet no one thinks they will fail or drift to Putin because of that. So why should the euro—plainly now a fading dream—be propped up? Why shouldn’t getting out be an option? Independent technical, financial, and moral support for democratic allies seeking exit would, in these conditions, help to stabilize an otherwise dangerous and destructive mood.

The story comes from everywhere now: non-euro countries fare much better than euro nations. Even in Germany, workers are being stiffed.

• The Euro Is A Disaster Even For The Countries That Do Everything Right (WaPo)

The euro might be worse for you than bankruptcy. That, at least, has been the case for Finland and the Netherlands, which have actually grown less than Iceland has since 2007. Iceland, you might recall, went bankrupt in 2008. Now, it’s true that Finland and the Netherlands have had their fair share of economic problems, but those should have been manageable. Neither country is a basket case, and both have done what they were supposed to do. In other words, they’ve followed the rules, and the results have still been a catastrophe. That’s because the euro itself is. Or, if you want to be polite, the common currency is “imperfect, and being imperfect is fragile, vulnerable, and doesn’t deliver all the benefits it could.” That was ECB chief Mario Draghi’s verdict on Thursday.

So what’s happened to them? Well, just your run-of-the-mill bad economic news. It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that Apple has kneecapped Finland’s economy. Its two biggest exports were Nokia phones and paper products, but, as the country’s former prime minister Alex Stubb has said, the iPhone killed the former and the iPad killed the latter. Now, the normal way to make up for this would be to cut costs by devaluing your currency, except that Finland doesn’t have a currency to devalue anymore. It has the euro. So instead it’s had to cut costs by cutting wages, which not only takes longer, but also causes more economic damage since you have to fire people to convince them to take pay cuts. The result has been a recession longer than anything in Finland’s living memory, longer even than its great depression in the early 1990s. It hasn’t helped, of course, that the rules of the euro zone have forced Finland’s government to cut its budget at the same time that all this has been happening.

It’s been a different kind of story in the Netherlands. Its goods are more than competitive abroad—its trade surplus is an absurd 10 % of economic output—but its domestic spending is a problem. The Netherlands had a huge housing bubble, fueled, in part, by the fact that interest payments are fully tax deductible, that has since deflated some 20%. That’s left Dutch households with a bigger debt burden than anyone else in the euro zone. On top of that, there’s been the usual austerity to keep its recovery from being much—or any—of one. Indeed, the Netherlands’ economy was slightly smaller at the end of 2014 than it was at the end of 2007. That’s a lot better than Finland, whose economy has shrunk 5.2% during that time, but it still lags the 1.1% growth Iceland has eked out.

Excellent.

• Blame the Banks (The Atlantic)

In buying various assets European banks were doing what banks are supposed to do: lending. But by doing so without caution they were doing exactly what banks are not supposed to do: lending recklessly. The European banks weren’t lending recklessly to only the U.S. They were also aggressively lending within Europe, including to the governments of Spain, Portugal, and Greece. In 2008, when the U.S. housing market collapsed, the European banks lost big. They mostly absorbed those losses and focused their attention on Europe, where they kept lending to governments—meaning buying those countries’ debt—even though that was looking like an increasingly foolish thing to do:

Many of the southern countries were starting to show worrying signs. By 2010 one of those countries—Greece—could no longer pay its bills. Over the prior decade Greece had built up massive debt, a result of too many people buying too many things, too few Greeks paying too few taxes, and too many promises made by too many corrupt politicians, all wrapped in questionable accounting. Yet despite clear problems, bankers had been eagerly lending to Greece all along. That 2010 Greek crisis was temporarily muzzled by an international bailout, which imposed on Greece severe spending constraints. This bailout gave Greece no debt relief, instead lending them more money to help pay off their old loans, allowing the banks to walk away with few losses.

It was a bailout of the banks in everything but name. Greece has struggled immensely since then, with an economic collapse of historic proportion, the human costs of which can only be roughly understood. Greece needed another bailout in 2012, and yet again this week. While the Greeks have suffered, the northern banks have yet to account financially, legally, or ethically, for their reckless decisions. Further, by bailing out the banks in 2010, rather than Greece, the politicians transferred any future losses from Greece to the European public. It was a bait-and-switch rife with a nationalist sentiment that has corrupted the dialogue since: Don’t look at our reckless banks; look at their reckless borrowing.

Legalese.

• Greece’s Debt Can Be Written Off – Whatever Wolfgang Schäuble Says (Guardian)

A vote in the Greek parliament means little to Germany’s finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble. The self-appointed guardian of the EU’s financial rulebook says Athens can vote as many times as it likes in favour of a deal that promises, even in the vaguest terms, to write off some of its colossal debts, but that doesn’t mean the rules allow it. In fact, as Schäuble delights in pointing out, any attempt at striking out Greek debt is, according to his advice, illegal. Yet Schäuble knows Greece’s debts are unsustainable unless some of them are written off – he has said as much on several occasions. So faced with its internal contradictions, he posits that the deal must fail and the poorly led Greeks exit the euro.

As a compromise, he repeated his suggestion on Tuesday that Greece leave the euro temporarily. Those who care more for maintaining the current euro currency bloc as a 19-member entity immediately spotted this manoeuvre as a one-way ticket with no way back for Greece. The Austrian chancellor, Werner Faymann, a centre-left social democrat, said Schäuble was “totally wrong” to create the impression that “it may be useful for us if Greece falls out of the currency union, that maybe we pay less that way”. Faymann, who has consistently taken a sympathetic line on Greece, showed his growing irritation at the German minister’s stance: “It’s morally not right, that would be the beginning of a process of decay … Germany has taken on a leading role here in Europe and in this case not a positive one.”

Greece and Faymann’s problem is that there are plenty of other forces at play pulling at the loose threads of the latest bailout deal. The IMF has said a big debt write-off is needed to prevent a proposed €86bn deal collapsing under the sheer weight of future liabilities and a reluctance in Greece to carry through reforms.

Bernanke weighs in.

• Greece And Europe: Is Europe Holding Up Its End Of The Bargain? (Ben Bernanke)

This week the Greek parliament agreed to European demands for tough new austerity measures and structural reforms, defusing (for the moment, at least) the country’s sovereign debt crisis. Now is a good time to ask: Is Europe holding up its end of the bargain? Specifically, is the euro zone’s leadership delivering the broad-based economic recovery that is needed to give stressed countries like Greece a reasonable chance to meet their growth, employment, and fiscal objectives? Over the longer term, these questions are evidently of far greater consequence for Europe, and for the world, than are questions about whether tiny Greece can meet its fiscal obligations.

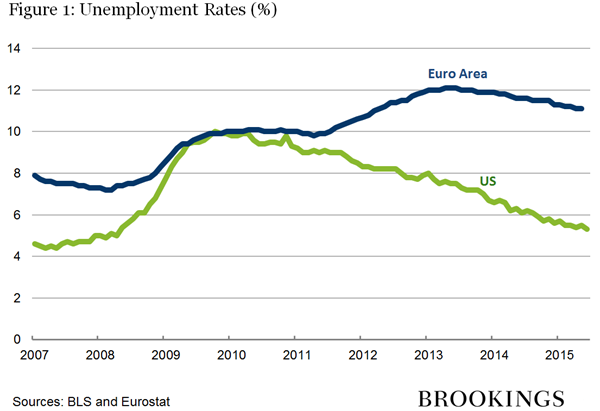

Unfortunately, the answers to these questions are also obvious. Since the global financial crisis, economic outcomes in the euro zone have been deeply disappointing. The failure of European economic policy has two, closely related, aspects: (1) the weak performance of the euro zone as a whole; and (2) the highly asymmetric outcomes among countries within the euro zone. The poor overall performance is illustrated by Figure 1 below, which shows the euro area unemployment rate since 2007, with the U.S. unemployment rate shown for comparison.

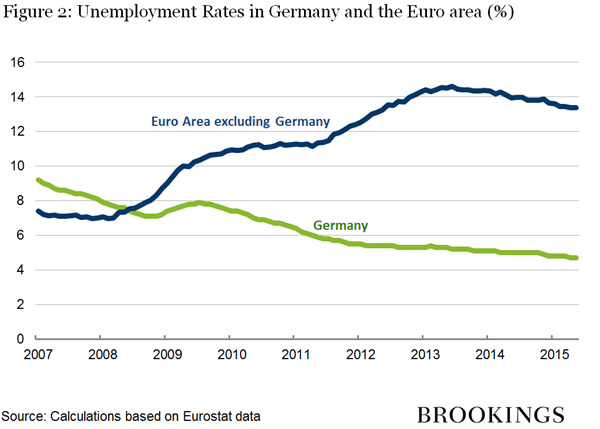

In late 2009 and early 2010 unemployment rates in Europe and the United States were roughly equal, at about 10% of the labor force. Today the unemployment rate in the United States is 5.3%, while the unemployment rate in the euro zone is more than 11%. Not incidentally, a very large share of euro area unemployment consists of younger workers; the inability of these workers to gain skills and work experience will adversely affect Europe’s longer-term growth potential. The unevenness in economic outcomes among countries within the euro zone is illustrated by Figure 2, which compares the unemployment rate in Germany (which accounts for about 30% of the euro area economy) with that of the remainder of the euro zone.

Currently, the unemployment rate in the euro zone ex Germany exceeds 13%, compared to less than 5% in Germany. Other economic data show similar discrepancies within the euro zone between the “north” (including Germany) and the “south.” The patterns illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 pose serious medium-term challenges for the euro area. The promise of the euro was both to increase prosperity and to foster closer European integration. But current economic conditions are hardly building public confidence in European economic policymakers or providing an environment conducive to fiscal stabilization and economic reform; and European solidarity will not flower under a system which produces such disparate outcomes among countries.

How Wolfie asset-stripped East Germany.

• Why Is Germany So Tough On Greece? Look Back 25 Years (Guardian)

It was 25 years ago, during the summer of 1990, that Schäuble led the West German delegation negotiating the terms of the unification with formerly communist East Germany. A doctor of law, he was West Germany’s interior minister and one of Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s closest advisers, the go-to guy whenever things got tricky. The situation in the former GDR was not too dissimilar from that in Greece when Syriza swept to power: East Germans had just held their first free elections in history, only months after the Berlin Wall fell, and some of the delegates from East Berlin dreamed of a new political system, a “third way” between the west’s market economy and the east’s socialist system – while also having no idea how to pay the bills anymore.

The West Germans, on the other side of the table, had the momentum, the money and a plan: everything the state of East Germany owned was to be absorbed by the West German system and then quickly sold to private investors to recoup some of the money East Germany would need in the coming years. In other words: Schäuble and his team wanted collateral. At that time almost every former communist company, shop or petrol station was owned by the Treuhand, or trust agency – an institution originally thought up by a handful of East German dissidents to stop state-run firms from being sold to West German banks and companies by corrupt communist cadres. The Treuhand’s mission: to turn all the big conglomerates, companies and tiny shops into private firms, so they could be part of a market economy.

Schäuble and his team didn’t care that the dissidents had planned to hand out shares of companies to the East Germans, issued by the Treuhand – a concept that incidentally led to the rise of the oligarchs in Russia. But they liked the idea of a trust fund because it operated outside the government: while technically overseen by the finance ministry, it was publicly perceived as an independent agency. Even before Germany merged into a single state in October 1990, the Treuhand was firmly in West German hands. Their aim was to privatise as many companies as possible, as soon as possible – and if you were to ask most Germans about the Treuhand today they would say it achieved that objective. It didn’t do so in a way that was popular with the people of East Germany, where the Treuhand quickly became known as the ugly face of capitalism. It did a horrible job in explaining the transformation to shellshocked East Germans who felt overpowered by this strange new agency. To make matters worse, the Treuhand became a hotbed of corruption.

“As for the future of the euro, it would no longer be the Greeks’ problem. What, they may say, has the euro done for us?”

• Greece Made The Wrong Choice (John Lloyd)

Former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis has, as Macbeth put it, “strutted and fretted his hour upon the stage.” But he will still be heard some more. While Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras pleaded for support Wednesday for a European Union “rescue” plan in which he said he didn’t believe, Varoufakis was busy ripping it apart. In a widely circulated blog, Varoufakis boiled down his belief to this: Greece had been reduced to the status of a slave state. While his words were clearly driven by anger and spite, he’s not entirely out of line. The agreement is, as Tsipras said, a kind of blackmail. The economist Simon Tilford described it as an order to “acquiesce to all our demands or we will evict you from the currency union.”

Pensions will be cut further, labor markets liberalized, working lives extended, collective bargaining “modernized,” and hiring and firing made easier. For a government that takes its inspiration from Karl Marx, this is a neo-liberal dousing. There are few enthusiasts for the deal: the most important of the skeptics is the IMF, which called for the euro zone creditors to allow a partial write-off of its €300+ billion debt, or at least permit a repayment pause for 30 years. In an ironic twist, the IMF, the creditor the Tsipras government most despised, is now its (partial) friend. Skeptics have focused not just on the impossibility of debt repayment, but also on the deepening poverty that will result from the agreement.

Francois Cabeau, an economist in Barclays Bank, told the French daily Figaro that the economy would continue to shrink by between 6 and 8% a year. Because the Greek economy has so few sectors where significant value is added other than shipping and tourism, it depends heavily on consumption — which is being further cut, thus prompting a vicious cycle and a further immiseration of the poor, elderly and sick. These conditions validate Varoufakis’ analysis. Greece is a country so firmly under the unremitting pressure of its creditors and so tied to foreign demands, that it may soon resemble an East European communist state in the high tide of Soviet power. Like two of these states — Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968 — Syriza made a failed attempt at a revolt, and was crushed.

[..] So should it leave the euro zone? The objections to a Grexit are twofold: first, that its currency — presumably a newly issued drachma — would be walloped by an unfavorable exchange rate as a result. Foreign goods and foreign travel would be priced out of many families’ reach. At the same time, as euro zone leaders have warned continually, a Grexit would also shake the euro to its foundations — and though the remaining 18 members could be protected, a precedent would be set that this is a contingent currency, with membership dependent on national conditions. That it would be bad is certain: but how much worse than staying in and swallowing bitter medicine? As for the future of the euro, it would no longer be the Greeks’ problem. What, they may say, has the euro done for us?

“The key (overlooked) question here is: Is this EU reflecting Europeans’ will? ”

• The Greek Crisis Represents The Humiliation Of European Democracy (Andrea Mammone)

Fears, disillusionment, uncertainty, and astonishment are mixed together by the hot wind blowing from Greece and the cold rain coming from some of Northern Europe. No, it is not a weather forecast. After the Greek referendum and the recent night-long negotiations, these are the feelings of many people across Europe. Even if the reality will probably be less apocalyptic, the truth is that democracy is being ridiculed around the EU. Some media from all around the world are, in fact, suggesting that Greece has been excessively humiliated and there is a strong attempt to force it out from the Eurozone. And this is not merely because one of the proposals from the summit stated that €50bn of Greek assets had to be handed over to an institution fundamentally controlled by Berlin.

These days Greece has been constantly at the centre of Europe’s microcosm. The “mother” of western democracy and inner culture, according to some, has to learn the lesson. It is a matter of mere power. They rejected austerity, potentially provoking another European downturn, and a default with unclear outcomes. Stories of poverty and unemployment are indeed in the eyes of everyone willing to see them. The situation is undermining the future of the European community. It is not simply opening the way for member states to be essentially pushed out by the strongest ones. Referring to the Greek early approach and a possible “exit”, EU Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker said that he could not “pull a rabbit out of a hat”. This is very true.

But early post-war politicians pulled many rabbits out when Europe had to be rebuilt after the war, and so one would expect a similar proficiency. This contemporary generation of European leaders might be instead remembered like the one leading to the disappearance of many transnational bonds established by Europeans. Europe is, then, really navigating with no compass. It has not a single voice. Socially, there seems to be no concern with people’s living standards. Politically, they lack any preoccupations with geo-politics, as some of the Mediterranean might fall under Putin’s influence. Budget and austerity are the main interests. As Pierre Moscovici, the socialist EU economic commissioner, in fact, put it, the “integrity” of the Eurozone has been saved with the novel agreement.

The key (overlooked) question here is: Is this EU reflecting Europeans’ will? Its image (and also Germany’s image) is seriously damaged even if all Greeks voted yes. For this reason the statement by the German European MP and chairman of the leading centre-right European People’s Party, Manfred Weber, that Europe is “based on solidarity, not a club of egoists” looks highly paradoxical, especially after what it is happening to Greece.

From Mason’s upcoming new book. Lots of technohappiness.

• The End Of Capitalism Has Begun (Paul Mason)

The 2008 crash wiped 13% off global production and 20% off global trade. Global growth became negative – on a scale where anything below +3% is counted as a recession. It produced, in the west, a depression phase longer than in 1929-33, and even now, amid a pallid recovery, has left mainstream economists terrified about the prospect of long-term stagnation. The aftershocks in Europe are tearing the continent apart. The solutions have been austerity plus monetary excess. But they are not working. In the worst-hit countries, the pension system has been destroyed, the retirement age is being hiked to 70, and education is being privatised so that graduates now face a lifetime of high debt. Services are being dismantled and infrastructure projects put on hold.

Even now many people fail to grasp the true meaning of the word “austerity”. Austerity is not eight years of spending cuts, as in the UK, or even the social catastrophe inflicted on Greece. It means driving the wages, social wages and living standards in the west down for decades until they meet those of the middle class in China and India on the way up. Meanwhile in the absence of any alternative model, the conditions for another crisis are being assembled. Real wages have fallen or remained stagnant in Japan, the southern Eurozone, the US and UK. The shadow banking system has been reassembled, and is now bigger than it was in 2008. New rules demanding banks hold more reserves have been watered down or delayed. Meanwhile, flushed with free money, the 1% has got richer.

Neoliberalism, then, has morphed into a system programmed to inflict recurrent catastrophic failures. Worse than that, it has broken the 200-year pattern of industrial capitalism wherein an economic crisis spurs new forms of technological innovation that benefit everybody. That is because neoliberalism was the first economic model in 200 years the upswing of which was premised on the suppression of wages and smashing the social power and resilience of the working class. If we review the take-off periods studied by long-cycle theorists – the 1850s in Europe, the 1900s and 1950s across the globe – it was the strength of organised labour that forced entrepreneurs and corporations to stop trying to revive outdated business models through wage cuts, and to innovate their way to a new form of capitalism.

“This El Niño hasn’t peaked yet, but by some measures it’s already the most extreme ever recorded for this time of year and could lead 2015 to break even more records than last year.”

• The Freakish Year in Broken Climate Records (Bloomberg)

The annual State of the Climate report is out, and it’s ugly. Record heat, record sea levels, more hot days and fewer cool nights, surging cyclones, unprecedented pollution, and rapidly diminishing glaciers.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issues a report each year compiling the latest data gathered by 413 scientists from around the world. It’s 288 pages, but we’ll save you some time. Here’s a review, in six charts, of some of the climate highlights from 2014.1. Temperatures set a new record It’s getting hot out there. Four independent data sets show that last year was the hottest in 135 years of modern record keeping. The map above shows temperature departure from the norm. The eastern half of North America was one of the few cool spots on the planet.

2. Sea levels also surge to a record The global mean sea level continued to rise, keeping pace with a trend of 3.2 millimeters per year over the last two decades. The global satellite record goes back only to 1993, but the trend is clear and consistent. Rising tides are one of the most physically destructive aspects of climate change. Eight of the world’s 10 largest cities are near a coast, and 40 % of the U.S. population lives in coastal areas, where the risk of flooding and erosion continues to rise.

3. Glaciers retreat for the 31st consecutive year Data from more than three dozen mountain glaciers show that 2014 was the 31st straight year of glacier ice loss worldwide. The consistent retreat of glaciers is considered one of the clearest signals of global warming. Most alarming: The rate of loss is accelerating over time.

4. There are more hot days and fewer cool nights Climate change doesn’t just increase the average temperature—it also increases the extremes. The chart above shows when daily high temperatures max out above the 90th %ile and nightly lows fall below the lowest 10th %ile. The measures were near their global records last year, and the trend is consistently miserable.

5. Record greenhouse gases fill the atmosphere By burning fossil fuels, humans have cranked up concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by more than 40 % since the Industrial Revolution. Carbon dioxide, the most important greenhouse gas, reached a concentration of 400 parts per million for the first time in May 2013. Soon we’ll stop seeing concentrations that low ever again.

The data shown are from the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. Data collection was started there by C. David Keeling of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in March 1958. This chart is commonly referred to as the Keeling curve.6. The oceans absorb crazy amounts of heat The oceans store and release heat on a massive scale. Over shorter spans of years to decades, ocean temperatures naturally fluctuate from climate patterns like El Niño and what’s known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. Longer term, oceans are absorbing even more global warming than the surface of the planet, contributing to rising seas, melting glaciers, and dying coral reefs and fish populations. In 2015 the world has moved into an El Niño warming pattern in the Pacific Ocean. El Niño phases release some of the ocean’s stored heat into the atmosphere, causing weather shifts around the world. This El Niño hasn’t peaked yet, but by some measures it’s already the most extreme ever recorded for this time of year and could lead 2015 to break even more records than last year.