Jack Delano Residents of Miss Disher’s rooming house for rail workers, Clinton, Iowa 1943

Whaddaya know.. Someone other than me gets the link between money velocity and deflation. And Guggenheim’s Scott Minerd adds negative rates for good measure.

• The Global Liquidity Trap Turns More Treacherous (Minerd)

For the first time since the Great Depression, the world is in a global liquidity trap. The unintended consequence of many central banks pushing negative interest rate policy is conjuring deflationary headwinds, stronger currencies, and slower growth — the exact opposite of what struggling economies need. But when monetary policy is the only game in town, negative rates are likely to beget even more negative rates, creating a perverse cycle with important implications for investors. When central banks reduce policy rates, their objective is to stimulate growth. Lower rates are designed to spur savers to spend, redirect capital into higher-return (ie riskier) investments, and drive down borrowing costs for businesses and consumers. Additionally, lower real interest rates are associated with a weaker currency, which stimulates growth by making exports more competitive.

In short, central banks reduce borrowing costs to kindle reflationary behaviour that helps growth. But does this work when monetary policy is driven through the proverbial looking glass of negative rates? There is a strong argument that when rates go negative it squeezes the speed at which money circulates through the economy, commonly referred to by economists as the velocity of money. We are already seeing this happen in Japan where citizens are clamouring for 10,000-yen bills (and home safes to store them in). People are taking their money out of the banking system to stuff it under their metaphorical mattresses. This may sound extreme, but whether paper money is stashed in home safes or moved into transaction substitutes or other stores of value like gold, the point is it’s not circulating in the economy.

The empirical data support this view — the velocity of money has declined precipitously as policymakers have moved aggressively to reduce rates. A decline in the velocity of money increases deflationary pressure. Each dollar (or yen or euro) generates less and less economic activity, so policymakers must pump more money into the system to generate growth. As consumers watch prices decline, they defer purchases, reducing consumption and slowing growth. Deflation also lifts real interest rates, which drives currency values higher. In today’s mercantilist, beggar-thy-neighbour world of global trade, a strong currency is a headwind to exports. Obviously, this is not the desired outcome of policymakers. But as central banks grasp for new, stimulative tools, they end up pushing on an ever-lengthening piece of string.

The BOJ and the ECB are already executing massive quantitative easing programmes, but as their balance sheets expand, assets available to purchase shrink. The BoJ now buys virtually all of the Japanese government bonds that are issued every year, and has resorted to buying exchange traded funds to expand its balance sheet. The ECB continues to grow the definition of assets that qualify for purchase as sovereign debt alone cannot satisfy its appetite for QE. As options for further QE diminish, negative rates have become the shiny new tool kit of monetary policy orthodoxy. If Doctor Draghi and Doctor Kuroda do not get the outcome they want from their QE prescriptions – which is highly likely – then more negative rates will be on the way.

Greater fools and bubbles.

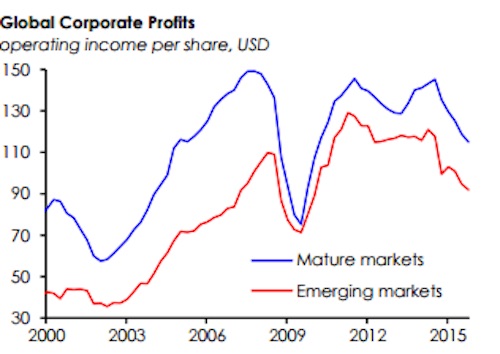

• Global Profits Recession Leaves Investors With Nowhere to Hide (BBG)

The profits recession is global – and that’s bad news for the world economy and for equity markets. So say researchers at the Institute of International Finance, a Washington-based association that represents close to 500 financial institutions from 70 countries. In their April “Capital Markets Monitor,” IIF executive managing director Hung Tran and his team blamed the global decline in earnings on poor productivity growth, weak demand and a general lack of pricing power. U.S. companies also are being squeezed by rising labor costs as they add people to their payrolls. The pervasiveness of the downturn means there’s nowhere for corporations to turn. “In the past, if you had poor performance at home, you could recoup and compensate for that with overseas investment,” Tran said in an interview.

“But if you suffer declines in profits domestically and internationally, you tend to retrench.” That in turn raises the odds of an economic recession. He put the chances of a U.S. downturn within two years at around 30 to 35% due to the earnings slump, up from 20 to 25%. The prolonged profits recession makes Tran and his associates skeptical that the recent rebound in global stock markets can last. They see prices stuck in a downward trend. “With profits expected to remain under pressure for the foreseeable future, this situation will eventually exert downward pressure on equity prices,” they wrote in their report.

Shares? No. Bonds? No.

• Global Bond Yield Plunge to Record 1.3% Is Flashing Warning Sign (BBG)

Global bond yields fell to a record, a warning sign on the worldwide economy. The yield on the Bank of America Global Broad Market Index plunged to 1.3%, the lowest level in almost 20 years of data. Bonds in the gauge have returned 3.6% in 2016, while the MSCI All Country World Index of shares has slumped 1.5%, including dividends. “This is a sign of global disinflation,” said Hideaki Kuriki at Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Asset Management. “The U.S. cannot pull up the world economy.” The Treasury 10-year note yield was little changed on Wednesday at 1.73% as of 10:19 a.m. in Tokyo, based on Bloomberg Bond Trader data. The price of the 1.625% security due in February 2026 was 99 2/32. The yield dropped to a record 1.38% in 2012. The Federal Reserve is scheduled to issue the minutes of its March 15-16 meeting Wednesday. Chair Janet Yellen said last week U.S. central bankers need to “proceed cautiously” in raising interest rates because the global economy presents heightened risks.

Don’t think a decade will do it.

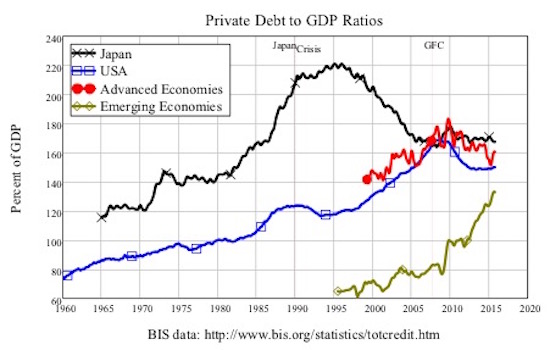

• Are We Facing A Global “Lost Decade”? (Steve Keen)

The era of low growth known as Japan’s “Lost Decade” commenced in 1990, and persists to this day. While most authors acknowledge that the seeds for the Lost Decade were sown by excessive credit growth in the preceding Bubble Economy years, only Richard Koo and Richard Werner have systematically argued that insufficient credit growth during the “Lost Decade” explains Japan’s now quarter-century long slump. Yet these arguments tell us more about the dilemmas facing today’s world economy than many more commonly accepted explanations of the current slowdown.

The insufficient credit growth story is rejected out of hand by most economists, for reasons summed up by Paul Krugman. From the perspective of mainstream economics, any event that negatively affects debtors is, to a large degree, offset by the positive effects of that event for creditors. Krugman therefore sees no possibility of Koo’s argument of “an entire economy being “balance-sheet constrained”: Maybe part of the problem is that Koo envisages an economy in which everyone is balance-sheet constrained, as opposed to one in which lots of people are balance-sheet constrained. I’d say that his vision makes no sense: where there are debtors, there must also be creditors, so there have to be at least some people who can respond to lower real interest rates even in a balance-sheet recession. (Krugman, 2013)

Koo is, however, correct: it IS possible for an entire economy to be balance-sheet constrained. Understanding why requires an appreciation of private credit creation that goes beyond the mere accounting truism that every entity’s liability is another entity’s asset. This paper will argue that the assumptions made by mainstream economists about the role of credit and banking in the economy are incorrect. When taking into account the “money creation” functions of banking, it becomes clear that the USA and most advanced economies as well as many emerging economies have joined Japan in being balance-sheet constrained, and face their own “lost decade” as a consequence of low credit growth. I will start with the empirical data and its implications, and then move on to the argument that an entire economy can be balance-sheet constrained.

We’ve neglected emerging markets recently.

• Default Tsunami Brewing (BBG)

Investors worried by a potential second wave of defaults in the U.S. should be even more concerned about emerging markets.Moody’s Investors Service says default rates currently stand at about 4% and could soar to as high as 14.9% by the end of the year under the most pessimistic scenario, Bloomberg News reports today. Its best-case projection is a 5.05% rate.Edward Altman, New York University professor and creator of the widely used Z-Score method for predicting bankruptcies, has also forecast rising U.S. defaults this year, saying in January that recession could follow even with a rate of less than 10%, given the increase in debt since the financial crisis.

Altman, a specialist in credit markets, hasn’t been able to create successful default rate statistics for emerging markets due to a lack of historical data, he told an audience at Hong Kong University last year. However, it was safe to assume that they would normally exceed those of developed markets such as the U.S., he concluded. If that’s the case, there’s trouble on the way. According to Standard & Poor’s, emerging markets recorded their highest number of defaults for 11 years in 2015, a tally of 26. The Bank of America Merrill Lynch High Yield Emerging Markets Corporate Plus index currently comprises 696 bonds, a number that’s risen from 346 eight years ago. Based on those numbers, the delinquency rate stands at only 3.7% (though the S&P figures don’t capture the entire universe of defaults).

A study by Moody’s published in February 2009 showed that the default rate among high-yield emerging-markets issues could reach as high as 22% in the five years following severe banking and sovereign crises. So far, most countries in the asset class have suffered currency and liquidity crises but have skirted the more severe sovereign and banking kind. A further cause for concern: Fitch Ratings said in January that 24% of companies in seven of the biggest emerging markets have raised money offshore. That increases their vulnerability to weakening currencies, an issue that’s dogging Chinese issuers. Fitch also said that the share of banks and sovereign ratings on negative outlook is at the highest since 2009.

China debt=Monopoloy money.

• China’s Global Investment Spree Is Fuelled By Debt (Economist)

[..] Chinese buyers, by and large, are far more indebted than the firms they are acquiring. Of the deals announced since the start of 2015, the median debt-to-equity ratio of Chinese buyers has been 71%, compared with 44% for the foreign targets, according to The Economist’s analysis of S&P Global Market Intelligence data. Cash cushions are generally also much thinner for Chinese buyers: their liquid assets are roughly a quarter lower than their immediate liabilities. The forbearance of their creditors makes these heavy debts more bearable in China than they would be elsewhere. But the Chinese buyers are financially stretched, all the same. Where, then, are they getting the money for the deals? For many, the answer is yet more debt. Chinese banks see lending to Chinese firms abroad as a safe way of gaining more international exposure.

The government has encouraged them to support foreign deals. As long as the firms to be acquired have strong cash flows, the banks are happy to lend against the targets’ balance-sheets, bringing debt to levels usually only seen in leveraged buy-outs. Foreign banks are also getting involved in some of the deals: HSBC, Credit Suisse, Rabobank and UniCredit are helping to arrange syndicated loans for ChemChina, which agreed to buy Syngenta, a Swiss seed and pesticide firm, for $43 billion. When the acquirers’ finances look shaky, bankers say they find solace in two things: that the deals themselves will generate returns and that the political pedigree of the buyers, especially that of state-owned companies, will protect them. “You have to trust that the acquirer has become too big to fail,” says an M&A adviser.

For the buyers, there are two strong financial rationales for the deals, albeit ones that highlight distortions in the Chinese market. First, debt-funded buyouts can actually make their debt burdens more tolerable. Take the case of Zoomlion, a construction-equipment maker with 83 times more debt than it earns before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation. It wants to buy Terex, an American rival with debt just 3.5 times larger than its earnings, for $3.4 billion. Even if the purchase consists entirely of borrowed cash, the combined entity would still have a debt-to-earnings multiple of roughly 18, a marked improvement for Zoomlion.

Second, Chinese buyers know that one key financial metric works to their advantage: valuations in the domestic stockmarket are much higher than abroad. The median price-to-earnings ratio of Chinese buyers is 56, twice that of their targets. In effect, this means they can issue shares domestically and use the proceeds to buy what, from their perspective, are half-price assets abroad. This also gives them the firepower to outbid rivals in bidding wars. To foreign eyes, it might look like the Chinese are overpaying. But so long as their banks and shareholders are willing to stump up the cash, Chinese companies see a window of opportunity.

Except in Beijing.

• China Bulls Become an Extinct Species (WSJ)

The definition of a China “bull” used to be those who saw the Chinese economy rushing full speed ahead into the distant future. Their vision wasn’t so far-fetched. Remember: Annual growth was still hitting double digits until 2010. As recently as 2014, Justin Lin Yifu, a former World Bank chief economist, was publicly confident that growth could roll along at 8% a year for another 20 years, with the right mix of economic overhauls to oil the wheels. The minority “bear” proposition was for a severe slowdown, somewhere in the mid-to-low single digits. An even rarer breed of “permabears” warned of collapse. How quickly calculations have changed. We haven’t yet reached the point where the former bear case has become the bull case, but we’re getting close.

At a recent workshop hosted by the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonpartisan U.S. think tank, participants—35 or so academic economists, Wall Street professionals and geopolitical strategists—lined up around three different growth scenarios for China. Only 31% chose the optimistic one, defined as 4% to 6% annual growth, dependent on leaders successfully implementing reforms; 61% foresaw a “lost decade” of 1% to 3% growth; the rest thought a so-called hard-landing, or contraction, was most likely. Of course it wasn’t a scientific survey, but what’s interesting is that apparently nobody considered the possibility that the Chinese government could deliver on its promise of “medium to fast” growth, meaning 6.5% or higher.

If the old-style bulls are virtually extinct as a species, a major reason is widespread skepticism that the Chinese leadership under President Xi Jinping is focused on economic transformation. Instead, Mr. Xi’s attention seems to be fixated on his anticorruption drive, cracking down on internal dissent, bringing the media to heel, firming up his control over the security forces and challenging the U.S. for dominance in the South China Sea. Ironically, those predicting a hard landing in the Council on Foreign Relations workshop might have had the best rationale for optimism. Michael Levi, a council fellow and one of the organizers, says this crowd thought that the economy hitting rock-bottom would galvanize the leadership into action and that China would “come out better on the other side.”

Liquidity vacuum.

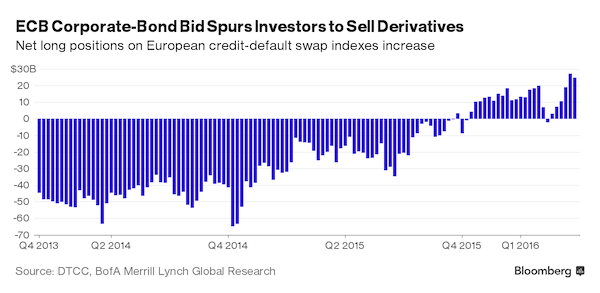

• Bond Investors Looking to Get Ahead of ECB Turn to Derivatives (BBG)

A rush for credit exposure in Europe is manifesting in the swaps market because investors are struggling to find enough bonds to satisfy their demand. The ECB’s plan to purchase corporate bonds is fueling demand for securities in anticipation of a rally when the purchases start. Investment-grade bond funds in euros had inflows each week since the ECB said on March 10 that it would expand measures to stimulate the economy. That’s already suppressed yields and made it harder to obtain the notes, making credit derivatives more attractive. Wagers on European credit-default swap indexes have more than doubled since the ECB’s announcement. Investors had sold a net $25 billion of protection as of March 25, near the highest since at least December 2013 and up from $11 billion as of March 4.

“There’s a dearth of bonds investors can get their hands on,” said Mitch Reznick at Hermes Investment Management. “In this liquidity vacuum, managers can use credit-default swaps as a proxy for the bonds that they can’t obtain in order to get longer in credit.” Investors placed the equivalent of $379 million into investment-grade bond funds in euros in the week through March 30, the fourth straight week of inflows, according to Bank of America. That helped push average borrowing costs for investment-grade companies to 1.07%, the lowest in almost a year, the bank’s bond index data show. They’re putting money into euro funds even as they withdraw from other segments, Bank of America said, citing EPFR Global data. Dollar and sterling funds had a combined $249 million of withdrawals in the period, the data show.

The ECB said it will start buying bonds from investment-grade companies in the euro area toward the end of the second quarter and investors are rushing to buy securities before then because they expect the purchases to sap liquidity and suppress yields even further. Some investors are also hoarding bonds, compounding the situation and making it more efficient to sell credit protection, Reznick said. “The quickest way to go long credit is by selling contracts tied to indexes in large size,” said Roman Gaiser at Pictet Asset Management. “That’s easier than buying lots of individual bonds. It’s a quick way of getting exposure to credit.”

I have no such hope.

• The Panama Papers Could Hand Bernie Sanders The Keys To The White House (Ind.)

The revelation that the rich and wealthy are shovelling money in overseas tax havens is not a particularly surprising one. Nevertheless, the sheer scale of the 11.5 million document leak from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonesca has whipped up an overdue storm and forced the issue of tax justice back on the agenda. It is likely that the Panama papers is just the tip of the iceberg, and if even more is revealed about the financial affairs of world leaders, the implication for global politics will be huge. The Democratic presidential primaries in the US have been characterised by surging anger at the global elite. The Panama papers scandal will only fuel popular indignation at the actions of perceived establishment figures – those who have stood idly by and allowed this huge miscarriage of justice to take place.

Although there have been no major American casualties over the leak at this stage, all of the presidential candidates will be questioned about the scandal. And nobody is going to be under more pressure than Hillary Clinton. For some Americans, she is the embodiment of a “global elite”, while Bernie Sanders is its antithesis. The huge leak exposes governments across the globe wilfully ignoring tax avoidance by the rich. Although Clinton has not been linked to any malfeasance in the leak, there is a sense that she is among the elite rich, some of whose members have benefited from such schemes. It has been revealed Clinton pushed through the Panama Free Trade Deal at the same time that Sanders vocally opposed it, citing research warning that it would strictly limit the government’s ability to clamp down on questionable or even illegal activity.

Even if the Clintons remain unmentioned in future tax bombshells, Sanders can continue to exploit the narrative that Clinton is part of the demographic responsible, and has assisted in flagrant abuses of the system through trade deals. As this scandal looks intent on dragging on, it is now increasingly likely that undecided voters will swing towards the Sanders camp in the vital primaries coming up, including New York. In a general election, Republican favourite Donald Trump’s alleged historic tax dodging will leave him in hot water in comparison to Sanders’ squeaky clean record. He is the only candidate who even speaks in terms of the 1% vs the 99%. Should he secure the Democratic nomination, early general election polls suggest Sanders would knock Trump out of the park.

“Sanders has opposed all free trade agreements in recent memory, such as NAFTA and the TPP. Clinton has supported them and even criticized Sanders for his lack of support.”

• Bernie Sanders Predicted The Panama Papers In 2011 (AHT)

[..] the Panama Papers implicate 140 world leaders from 50 countries in stashing enormous sums of untaxed money in offshore shell corporations. Of course, this is part and parcel of the 1%, but the ubiquitousness shown in the leaks is astonishing. [..] No American leaders have been named in the leak as yet, but the editor of Süddeutsche Zeitung told other journalists “Just wait for what is coming next” in regards to American empire. Nevertheless, Senator and Democratic primary contender Bernie Sanders may very well have already come out ahead. In October 2011, Sanders criticized the Panama trade pact on the Senate floor.“Panama’s entire annual economic output is only $26.7 billion a year, or about two-tenths of one% of the U.S. economy. No one can legitimately make the claim that approving this free trade agreement will significantly increase American jobs.”

Sanders then asks the Senate, “why would we be considering a standalone free trade agreement with Panama?” The agreement in question, which was ultimately passed despite Sanders’ objections, is called The United States—Panama Trade Promotion Agreement (TPA). Sanders then answered his own question in a haunting premonition of things to come: “Well it turns out that Panama is a world leader when it comes to allowing wealthy Americans and large corporations to evade U.S. taxes by stashing their cash in offshore tax havens; and the Panama free trade agreement will make this bad situation much worse. Each and every year, the wealthiest people in our country and the largest corporations evade about $100 billion in U.S. taxes through abusive and illegal offshore tax havens in Panama and other countries…”

The D.C.-based progressive think tank Citizens for Tax Justice proclaims “that tax haven use is ubiquitous among America’s largest companies,” citing its volumes of research. In 2014, Fortune 500 companies held more than $2.1 trillion in accumulated profits offshore in order to evade taxes. Hillary Clinton, Sanders’ opponent in the Democratic primary, argued vehemently for the TPA in 2011. “The Free Trade Agreements passed by Congress tonight will make it easier for American companies to sell their products to South Korea, Colombia and Panama, which will create jobs here at home,” part of Clinton’s 13 October, 2011 statement read. Strangely enough, her full statement no longer exists on the State Department’s website. Sanders has opposed all free trade agreements in recent memory, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Clinton has supported them and even criticized Sanders for his lack of support.

We need a Delaware Papers.

• How America Became A World Leader In Tax Avoidance (Salon)

What we have not yet seen is any U.S. individual implicated in the leak, which seems unlikely given our stable of international wealth. The editor of Süddeutsche Zeitung, the German newspaper which first received the documents, promises there will be more to come. But one reason why Americans haven’t yet been implicated is that they already have a perfectly good place for their tax avoidance schemes: right here in the United States. While several developed countries are already moving to reduce the anonymity behind shell companies, including a public registry of “beneficial ownership” information in the United Kingdom and a directive to collect similar information throughout the European Union, the United States has resisted such transparency. According to recent research, the United States is the second-easiest country in the world to obtain an anonymous shell corporation account. (The first is Kenya.) You can create one in Delaware for your cat.

While we force foreign financial institutions to give up information on accounts held by U.S. taxpayers through the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act of 2010, we don’t reciprocate by complying with international disclosure requirements standardized by the OECD and agreed to by 97 other nations. As a result, the U.S. is becoming one of the world’s foremost tax havens. Several states – Delaware, Nevada, South Dakota, Wyoming – specialize in incorporating anonymous shell corporations. Delaware earns between one-quarter and one-third of their budget from incorporation fees, according to Clark Gascoigne of the FACT Coalition. The appeal of this revenue has emboldened small states, and now Wyoming bank accounts are the new Swiss bank accounts. America has become a lure, not only for foreign elites looking to seal money away from their own governments, but to launder their money through the purchase of U.S. real estate.

In addition, if the United States really wanted to stop Panama or the Cayman Islands or other offshore tax havens from allowing the wealthy to avoid hundreds of billions in payments, they could do so in about 15 minutes. Our recent free trade deal with Panama allegedly prevents Americans from creating offshore tax havens there, but in general, such tax information exchanges are insufferably weak. And the little America does abroad to police tax evasion dwarfs the next to nothing we do at home. The intertwining of global and political elites makes tax avoidance, whether legal or illegal, a secondary concern for the country, regardless of how it robs the country of resources and promotes the conception of a two-tiered economic and justice system where the upper class need not follow the same rules as the rest of us. Our politicians made a consistent choice that this rampant tax avoidance doesn’t bother them.

“Anonymous shell companies have been used to rip off Medicare,” said Gascoigne. “They’ve been used to evade U.S. sanctions. Arms dealers like Viktor Bout, the so-called Merchant of Death, used U.S. shell companies to launder money.” Indeed, Mossack Fonseca has affiliated offices in Wyoming, Nevada, and Florida. America is up to its eyeballs in this style of corruption.

“..the U.S. is just as big a secrecy jurisdiction as so many of these Caribbean countries and Panama. We should not want to be the playground for the world’s dirty money, which is what we are right now.”

• Panama Has Company as Bank-Secrecy Holdout: America (BBG)

Panama and the U.S. have at least one thing in common: Neither has agreed to new international standards to make it harder for tax evaders and money launderers to hide their money. Over the past several years, amid increased scrutiny by journalists, regulators and law enforcers, the global tax-haven landscape has shifted. In an effort to catch tax dodgers, almost 100 countries and other jurisdictions have agreed since 2014 to impose new disclosure requirements for bank accounts, trusts and some other investments held by international customers – standards issued by the OECD, a government-funded international policy group. Places like Switzerland and Bermuda are agreeing, at least in principle, to share bank account information with tax authorities in other countries.

Only a handful of nations have declined to sign on. The most prominent is the U.S. Another, Panama, is at the center of a storm over tax evasion and global cash flight that broke out over the weekend. A law firm there helped set up tens of thousands of shell companies, according to a report by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. ICIJ and other news organizations published reports they said showed global efforts to hide wealth, undertaken by global politicians and the ultra-rich, with the aid of banks and lawyers. The central tool: shell companies that people used to shield the identity of the owners’ assets. While such structures can be legal, they can also support efforts to avoid taxes.

The latest reporting “underscores the secrecy in Panama,” said Stefanie Ostfeld, the acting head of the U.S. office of the anti-corruption group Global Witness. “What’s lesser known, is the U.S. is just as big a secrecy jurisdiction as so many of these Caribbean countries and Panama. We should not want to be the playground for the world’s dirty money, which is what we are right now.” Advisers around the world are increasingly using the U.S. resistance to the OECD’s standards as a marketing tool — attracting overseas money to U.S. state-level tax and secrecy havens like Nevada and South Dakota, potentially keeping it hidden from their home governments.

[..] “The U.S. doesn’t follow a lot of the international standards, and because of its political power, it’s able to continue,” said Bruce Zagaris an attorney at Berliner Corcoran & Rowe who specializes in international tax and money laundering regulations. “It’s basically the only country that can continue to do that. Others like Panama have tried, but Panama can’t punch as high as the U.S.” Indeed, in a statement issued Monday by OECD secretary general Angel Gurria, the OECD said “Panama is the last major holdout that continues to allow funds to be hidden offshore from tax and law-enforcement authorities.” The statement didn’t mention the U.S., which is the OECD’s largest funder.

Icelanders want a lot more: for the entire ruling class to be replaced.

• Panama Secrecy Leak Claims First Casualty as Iceland PM Quits (BBG)

The Panama secrecy leak claimed its first casualty after Iceland’s Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson resigned following allegations he had sought to hide his wealth and dodge taxes. The decision was announced in parliament after the legislature had been the focus of street protests that attracted thousands of Icelanders angered by the alleged tax evasion efforts of their leader. Gunnlaugsson, who will step down a year before his term was due to end, gave in to mounting pressure from the opposition and even from corners of his own party. “What this exemplifies more than anything else is that there’s a growing lack of tolerance over the way that the international financial system has been gamed and rigged by corrupt elites,” Carl Dolan, director of Transparency International’s EU division, said in a phone interview from Brussels.

The Panama files, printed in newspapers around the world, showed that the 41-year-old premier and his wife had investments placed in the British Virgin Islands, which included debt in Iceland’s three failed banks. The leaked documents therefore also raise questions about Gunnlaugsson’s role in overseeing negotiations with the banks’ creditors. Ironically, the offshore investments were held while Iceland enforced capital controls. Gunnlaugsson is the second Icelandic premier to resign amid a popular uprising, after Geir Haarde was forced out following protests in 2009. Gunnlaugsson always looked to be the most vulnerable of the politicians implicated in the documents. From Moscow to Islamabad and Buenos Aires, most public figures have managed to beat off the revelations with either outrage, denial or indifference.

None of those tactics worked for Gunnlaugsson, whose first response was to walk out of an interview with Swedish TV, a clip that went viral after the leaks were published on Sunday. “The Iceland PM is the tip of the iceberg in terms of how much political instability we’ll see long-term on the basis” of the leaks, Ian Bremmer, president of the New York-based Eurasia Group, said by phone on Tuesday. Iceland’s electorate balked at the alleged tax evasion and Gunnlaugsson’s initial refusal to budge. Police on Monday erected barricades around the parliament in Reykjavik as protesters beat drums and pelted the legislature with eggs and yogurt. Almost 10,000 people gathered, according to police, while organizers said the figure was twice as high. Thousands more had signed up on Facebook to attend a second round of protests that was due to take place on Tuesday afternoon.

Will we ever find out how these files saw the light of day?

• Mossack Fonseca Says Data Hack Was External, Files Complaint (Reuters)

The Panamanian lawyer at the center of a data leak scandal that has embarrassed a clutch of world leaders said on Tuesday his firm was a victim of a hack from outside the company, and has filed a complaint with state prosecutors. Founding partner Ramon Fonseca said the firm, Mossack Fonseca, which specializes in setting up offshore companies, had broken no laws and that all its operations were legal. Nor had it ever destroyed any documents or helped anyone evade taxes or launder money, he added in an interview with Reuters. Company emails, extracts of which were published in an investigation by the U.S.-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and other media organizations, were “taken out of context” and misinterpreted, he added.

“We rule out an inside job. This is not a leak. This is a hack,” Fonseca, 63, said at the company’s headquarters in Panama City’s business district. “We have a theory and we are following it,” he added, without elaborating. “We have already made the relevant complaints to the Attorney General’s office, and there is a government institution studying the issue,” he added, flanked by two press advisers. Governments across the world have begun investigating possible financial wrongdoing by the rich and powerful after the leak of more than 11.5 million documents, dubbed the “Panama Papers,” from the law firm that span four decades. The papers have revealed financial arrangements of prominent figures, including friends of Russian President Vladimir Putin, relatives of the prime ministers of Britain and Pakistan and Chinese President Xi Jinping, and the president of Ukraine.

On Tuesday, Iceland’s prime minister, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, resigned, becoming the first casualty of the leak. “The (emails) were taken out of context,” Fonseca said. He lamented what he called journalistic activism and sensationalism, extolling his own investigative research credentials as a published novelist in Panama. “The only crime that has been proven is the hack,” Fonseca said. “No one is talking about that. That is the story.” France announced on Tuesday it would put the Central American nation back on its blacklist of uncooperative tax jurisdictions. Alvaro Aleman, chief of staff to President Juan Carlos Varela, told a news conference the government could respond with similar measures against France, or any other country that followed France’s lead.

Question is, even if he held no shares: did he know what his dad did?

• David Cameron Left Dangerously Exposed By Panama Papers Fallout (G.)

David Cameron was left dangerously exposed on Tuesday after repeatedly failing to provide a clear and full account about links to an offshore fund set up by his late father, as the storm over the Panama Papers gathered strength in both the UK and elsewhere around the world. The prime minister and his office have now offered three partial answers about the fund set up by his father Ian, which avoided ever paying tax in Britain. The key unanswered question is whether the prime minister’s family stands to gain in the future from his father’s company, Blairmore, an investment fund run from the Bahamas. After Downing Street said on Monday that the fund was a “private matter”, a journalist asked Cameron about it during a visit to Birmingham on Tuesday. Cameron replied: “I own no shares, no offshore trusts, no offshore funds, nothing like that. And, so that, I think, is a very clear description.”

He dodged the key part of the question about whether he or his family stood to benefit. Having failed to satisfy reporters, Downing Street issued a further statement that Cameron’s wife and children also do not benefit from offshore funds but again left the main question about the future unanswered. The Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn, who had called earlier in the day for an independent investigation, told the Guardian: “Three times Downing Street has been asked to provide a full and comprehensive answer. The public has a right to know the truth. “We need to know the full extent of the links between Britain and the web of tax avoidance and evasion revealed by the Panama Papers at all levels.”

[..] The row embroiling Cameron picked up pace on Tuesday morning when Corbyn responded to Downing Street’s assertion that the matter was private by telling reporters: “Well, it’s a private matter insofar as it’s a privately-held interest. But it’s not a private matter if tax is not being paid. So an investigation must take place, an independent investigation, unprejudiced, to decide whether or not tax has been paid.” Later in the day, Cameron told reporters: “In terms of my own financial affairs, I own no shares. I have a salary as prime minister and I have some savings, which I get some interest from and I have a house, which we used to live in, which we now let out while we are living in Downing Street and that’s all I have.”

More on the nonsense prevalent in ‘mainstream’ economics. No clue about risk.

• The Enduring Certainty Of Radical Uncertainty (John Kay)

The excellent new book by Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England, is inevitably noticed mainly for its views on banking regulation and the outlook for the eurozone. For me the most important message of The End of Alchemy is its emphasis on radical uncertainty — or, to quote Donald Rumsfeld, former US defence secretary: “The things we do not know we do not know.” That emphasis reflects the parallel intellectual paths Lord King and I have taken since we were young dons 40 years ago. In a book published in 1976, economist Milton Friedman disparaged a tradition that “drew a sharp distinction between risk, as referring to events subject to a known or knowable probability distribution, and uncertainty, as referring to events for which it was not possible to specify numerical probabilities”.

Friedman went on: “I have not referred to this distinction because I do not believe it is valid. We may treat people as if they assigned numerical probabilities to every conceivable event.” Asked, “Who will win the war?”, Churchill might have responded, “Britain, with probability 0.7”; and Hitler with a similar answer but perhaps different number. However absurd, this is what we were taught and what we passed on to the next generation of students. It seemed an exciting time for young turks in finance; insider trading in an old-boy network was to be superseded by a new generation of quants and rocket scientists. We had the mathematical tools to revolutionise investment banking. Our theory came to underpin the risk models used in financial institutions and imposed by regulators.

But Friedman was wrong. There really are limits to the range of problems susceptible to the mathematics of classical statistics. He was, erroneously, rejecting the concept of radical uncertainty described 50 years earlier by the economists John Maynard Keynes and Frank Knight. “By uncertain knowledge,” wrote Keynes in 1921, “I do not mean merely to distinguish what is known for certain from what is only probable. The sense in which I am using the term is that in which the prospect of a European war is uncertain…There is no scientific basis to form any calculable probability whatever. We simply do not know.”

While the long-term future of interest rates or copper prices, about which Keynes also speculated, might be approached probabilistically, questions about the social system 50 years hence are too open-ended, and the outcomes too varied and insufficiently specific, to be described in probabilistic terms. A recent book on superforecasters, co-written by Philip Tetlock, illustrates the point well. By trying to turn multi-faceted questions into ones precise enough to enable those who proffer answers to be assessed for their accuracy, he makes the questions narrow and uninteresting: “How will the Syrian war develop” and “How will Europe manage its refugee crisis?” become: “How many Syrian refugees will land in Europe in 2016?”

To get rid of refugees, the EU has no qualms about shamelessly linking them to terrorism.

• EU Executive To Present Steps To Tighten External Border Controls (Reuters)

The EU’s executive will propose on Wednesday a raft of technical measures to strengthen its external borders as it seeks to tackle both an uncontrolled influx of migrants and security threats following deadly attacks in Paris and Brussels. More than 160 people were killed in the November shooting and bombing attacks in Paris and suicide bombings in Brussels in March. The deadly strikes, claimed by Islamic State, strengthened the hand of those campaigning for tighter security checks and data sharing against those who warn of the risks of abuse and undermining privacy through enhanced surveillance. In its proposal on Wednesday, seen by Reuters ahead of official publication, the European Commission said the carnage in Paris and Brussels “brought into sharper focus the need to join up and strengthen the EU’s border management, migration and security cooperation.”

Europol chief Rob Wainwright highlighted separately on Tuesday an “indirect link” between Europe’s migration crisis, which saw more than a million people arriving over the last year, and the Islamist militant threat, saying some militants had used the chaotic migrant influx to sneak in. EU border agency Frontex also said that two of the perpetrators of the Nov. 13 attacks in Paris had entered through Greece and been registered by Greek authorities after presenting fraudulent Syrian documents. “EU citizens are known to have crossed the external border to travel to (Middle East) conflict zones for terrorist purposes and pose a risk upon their return. There is evidence that terrorists have used routes of irregular migration to enter the EU,” the Commission said in its proposal.

But the EU has a dozen-or-so different sets of fragmented databases for border management and law enforcement that are plagued with gaps and often not inter-operable. Custom authorities’ data are held largely separate. The Commission on Wednesday will therefore set out technical proposals to beef them up and improve the way they communicate with one another, including a joint search interface.

Rich Europeans have one priority only: to remain rich and privileged.

• With New Deal, A Refugee’s Rights Come Down To Luck (Reuters)

Through a barbed wire fence, 17-year-old Syrian refugee Asma attempted to tell us about her journey to Greece. We didn’t have much time to listen. Greek police officers were breathing down our necks, threatening to arrest us unless we left. We learned that Asma traveled alone on a tiny rubber boat from Turkey, and broke her arm – still wrapped in a white bandage – when a building collapsed in her hometown of Daraa, the birthplace of the Syrian uprising. As she started to tell us about her hope for a fresh start in Germany, the policemen issued their final warning before escorting us off Moria camp’s fenced perimeter. “We’re animals now,” Asma shouted after us. “We’re no longer humans.” If Turkey is a crowded departure hall to a better life, Greece is now a transit lounge for those who’ve missed their connection.

Many will never move onward to northern Europe; others will only move backward. With more than 52,000 refugees and migrants stranded in the country, Greece has become exactly what Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras warned months ago: a “warehouse of souls.” And the new deal between the EU and Turkey, intended to stem the refugee flow into Europe, only redirects it. Under the terms of the deal, most asylum seekers who illegally travel to Greece from Turkey are to be sent back to Turkey. The first returns took place Monday at dawn. For every returnee to Turkey, a Syrian living in a Turkish refugee camp will be legally resettled by plane to EU countries. As such, a refugee’s rights come down to luck. If Asma had arrived in Greece last month, she’d likely be in Germany by now.

If she had arrived three weeks ago, she’d likely be trapped in a makeshift camp on the Greece-Macedonia border – not much of an upgrade, but she’d have more access to the outside world than she does in Lesbos, where more than 3,000 refugees are locked in a former military base. For refugees like her, who arrived after the deal took effect March 21, most will be sent back to Turkey; that is, unless they can individually prove Turkey is “unsafe” for them. Even many Syrians, Iraqis and Eritreans – who have special protections under international law and qualify for the EU’s official “relocation” program – will be returned to Turkey. Officials insist the deal isn’t about restricting access to asylum in Europe, but eliminating illegal smuggling routes that sent more than 1 million refugees and migrants to Europe from Turkey over the past year.

Indeed, as ferryboats carrying migrants returned to Turkey on Monday, Syrians from Turkish refugee camps were being resettled in Germany and Finland. But this “one-for-one” deal struck in Brussels – which creates a kind of human carousel – is disconnected from the reality on the ground in Greece. The deal’s byzantine complexities have sowed confusion, fear and anxiety among asylum-seekers and authorities alike. Humanitarian groups such as the United Nations refugee agency, Doctors Without Borders and Save the Children have suspended activities on several Greek islands to protest its terms. They argue that the deal turns reception centers for refugees into inhumane, de facto detention facilities.

This is going to get so messy..

• Greece Pauses Deportations As Asylum Claims Mount (AP)

Authorities in Greece have temporarily suspended deportations to Turkey and acknowledged that most migrants and refugees detained on Greek islands have applied for asylum. The EU began sending back migrants Monday under an agreement with Turkey, but no transfers were planned Tuesday. Maria Stavropoulou, director of Greece’s Asylum Service, told state TV that some 3,000 people held in deportation camps on the islands are seeking asylum, with the application process to formally start by the end of the week. She says asylum applications typically take about three months to process, but would be “considerably faster” for those held in detention.