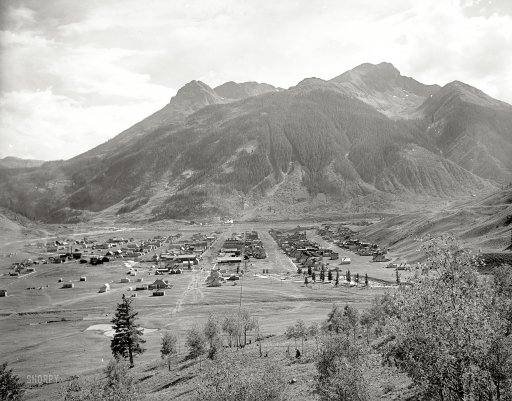

William Henry Jackson Silverton, Colorado 1901

An Automatic Earth afficionado who goes by the moniker GeoLib posted something in the comments section for yesterday’s Debt In The Time Of Wall Street that I think deserves a better fate than to be stuck there. He makes a gracious connection between 19th century American writer, politician and political economist Henry George, in particular his book Progress and Poverty, which in its day was a huge bestseller, and Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, who, in GeoLib’s words, “is graciously returning the book to us”.

Consider it economics 101 for those who look at the field from the outside, or consider it that which could have been, but is not. And then think about why that is. George’s words show us that we could do much better than we do, but we don’t want to. That is not only true in economics, of course, we’re making an awful mess of things in just about every field we try our hand at. Try the earth, or our relationships with others. That says quite a lot about not only our character, but also about our future.

I’ll give you GeoLib’s piece first, followed by an article he cites by professor Mason Gaffney on George’s work. I think it’s interesting to note that Gaffney posits George was so successful at presenting his argument for ‘socializing land rents through taxation’ that this very success became the root of its failure.

GeoLib: In 1879 Henry George published Progress and Poverty. The book was an international sensation, at the time outsold only by the Bible. It remains economics’ No. 1 best seller.

Mason Gaffney: “George came out of a raw, naive new colony, California, as a scrappy marginal journalist. Yet his ideas exploded through the sophisticated metropolitan world as though into a vacuum. His book sales were in the millions. Seven short years after publishing Progress and Poverty in remote California he nearly took over as Mayor of New York City, the financial and intellectual capital of the nation.

Three more years and he was a major influence in sophisticated Britain. In 1889, incredibly, he became “adviser and field-general in land reform strategy” to the Radical wing of the Liberal Party in Britain. It adopted a land-tax plank after 1891 (The “famous Newcastle Programme”), and came to carry George’s (muted) policies forward under successive Liberal Governments of Campbell-Bannerman, Asquith, and Lloyd George.“

The book, you see, explained poverty. It answered why progress does not and cannot eradicate poverty. Disconcertingly for many, it also provided the solution – the Single Tax on land value aka Land Value Taxation (LVT). “The “single tax” is so simple, so fundamental, and so easy to carry into effect that I have no doubt that it will be about the last land reform the world will ever get. People in this world are not often logical.” – Clarence Darrow

The land reform/single tax movement in Britain was strong enough to bend the Liberal govt to its will having delivered it a landslide in 1906. By 1910 there was a constitutional crisis over LVT. Gaffney argues that Henry George was deliberately written out of economics because he was too dangerous to the rentier state, the feudal core of capitalism. Maybe, and WW1 killed a generation of land reformers – this perhaps explains the absence of collective memory.

The very language of George’s economics – classical economics – was changed – neoclassical economics deletes the concept of land – we talk of real estate because we can’t understand that land itself is priced. We can’t see that real estate booms and busts are actually land value booms and busts and thus can never stray into the territory where the rentier makes so much money. Land is just another form of capital – a costly intellectual regression.

Greek Finance Minister Varoufakis meets Schäuble in Berlin Thu 5 Feb: “Our government will stop at nothing to combat not only corruption, tax evasion, tax immunity, inefficiency and waste but also a whole political economy underpinning the ethos and the conventions of crippling rent seeking.” The rentier is an obscure, quaint character but he is the key character for Varoufakis. Progress and Poverty is all about the rentier and Varoufakis is graciously returning the book to us.

In a democratic setting, playing a Georgist card can be a powerful move. Neither Right nor Left can criticise a Georgist position because Georgist reform gives them both what they want. George, as Mason Gaffney writes “had a way of taking two problems and composing them into one solution. He took two polar philosophies, collectivism and individualism, and synthesized a plan to combine the better features, and discard the worse features, of each.”

“Thus, George would cut the Gordian knot of modern dilemma-bound economics by raising demand, raising supply, raising incentives, improving equity, freeing up the market, supporting government, fostering capital formation, and paying public debts, all in one simple stroke. It’s quite a stroke, enough to leave one breathless.“ “George’s proposal lets us lower taxes on labour without raising taxes on capital. Indeed, it lets us lower taxes on both labour and capital at once, and without lowering public revenues.“ “Ultimately, Georgist policy saves the cost of civil disturbances and insurrections, and/or the cost of putting them down.”

Excerpts from The Corruption of Economics by Mason Gaffney

Introduction: The Power of Neo-Classical Economics

Neoclassical economics is the idiom of most economic discourse today. It is the paradigm that bends the twigs of young minds. Then it confines the florescence of older ones, like chicken-wire shaping a topiary. It took form about a hundred years ago, when Henry George and his reform proposals were a clear and present political danger and challenge to the landed and intellectual establishments of the world. Few people realize to what a degree the founders of Neoclassical economics changed the discipline for the express purpose of deflecting George, discomfiting his followers, and frustrating future students seeking to follow his arguments. The stratagem was semantic: to destroy the very words in which he expressed himself. Simon Patten expounded it succinctly. “Nothing pleases a … single taxer better than … to use the well-known economic theories … [therefore] economic doctrine must be recast” (Patten 1908; Collier, 1979).

George believed economists were recasting the discipline to refute him. He states so, in his last book, The Science of Political Economy. George’s self-importance was immodest, it is true. However, immodesty may be objectivity, as many great talents from Frank Lloyd Wright to Muhammad Ali and Frank Sinatra have displayed. George had good reasons, which we are to demonstrate. George’s view may even strike some as paranoid. That was this writer’s first impression, many years ago. I have changed my view, however, after learning more about the period, the literature, and later events.

Having taken shape in the 1880-1890s, Neo-Classical Economics (henceforth NCE) remained remarkably static. Major texts by Marshall, Seligman, and Richard T. Ely, written in the 1890s, went through many reprintings each over a period of 40 years with few if any changes. Not until 1936 was there another major “revolution,” and that was hived off into a separate compartment, macro-economics, and contained there so as not to disturb basic tenets of NCE. Compartmentalization, we will see in several instances, is the common NCE defense against discordant data and reasoning.

J. B. Clark’s capital theory “… gives the appearance of being specially tailored to lead to arguments for use against George” (Collier, 1979). “The probable source from which immediate stimulation came to Clark was the contemporary single tax discussion” (Fetter, 1927). “To date, capital theory in the Clark tradition has provided the basis for virtually all empirical work on wealth and income” (Dewey, 1987; cf. Tobin, 1985). Later writers have added fretworks, curlicues and arabesques beyond counting, and achieved more isolation from history, and from the ground under their feet, than in Patten’s dreams, but all without disturbing the basic strategy arrived at by 1899, tailored to lead to arguments against Henry George.

To most modern readers, probably George seems too minor a figure to have warranted such an extreme reaction. This impression is a measure of the neo-classicals’ success: it is what they sought to make of him. It took a generation, but by 1930 they had succeeded in reducing him in the public mind. In the process of succeeding, however, they emasculated the discipline, impoverished economic thought, muddled the minds of countless students, rationalized free-riding by landowners, took dignity from labor, rationalized chronic unemployment, hobbled us with today’s counterproductive tax tangle, marginalized the obvious alternative system of public finance, shattered our sense of community, subverted a rising economic democracy for the benefit of rent-takers, and led us into becoming an increasingly nasty and dangerously divided plutocracy.

The crabbed spirit of neo-classical economics

Neo-classical economics makes an ideal of “choice.” That sounds good, and liberating, and positive. In practice, however, it has become a new dismal science, a science of choice where most of the choices are bad. “TANSTAAFL” (There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch) is the slogan and shibboleth. Whatever you want, you must give up something good. As an overtone there is even a hint that what one person gains he must take from another. The theory of gains from trade has it otherwise, but that is a heritage from the older classical economists.

Henry George, in contrast, had a genius for reconciling-by-synthesizing. Reconciling is far better than merely compromising. He had a way of taking two problems and composing them into one solution. He took two polar philosophies, collectivism and individualism, and synthesized a plan to combine the better features, and discard the worse features, of each. He was a problem-solver, who did not suffer incapacitating dilemmas and standoffs.

As policy-makers, neo-classical economists present us with “choices” that are too often hard dilemmas. They are in the tradition of Parson Malthus, who preached to the poor that they must choose between sex or food. That was getting right down to grim basics, and is the origin of a well-earned epithet, “the dismal science.” Most modern neo-classicals are more subtle (although the fascist wing of the otherwise admirable ecology movement gets progressively less so). Here are some dismal dilemmas that neo-classicals pose for us today. For efficiency we must sacrifice equity; to attract business we must lower taxes so much as to shut the libraries and starve the schools; to prevent inflation we must keep an army of unfortunates unemployed; to make jobs we must chew up land and pollute the world; to motivate workers we must have unequal wealth; to raise productivity we must fire people; and so on.

The neo-classical approach is the “trade-off.” A trade-off is a compromise. That has a ring of reasonableness to it, but it presumes a zero-sum condition. At the level of public policy, such “trade-offs” turn into paralyzing stand-offs, where no one gets nearly what he wants, or could get. It overlooks the possibility of a reconciliation, or synthesis, instead. In such a resolution, we are not limited by trade-offs between fixed A and B: we get more of both.

Popular responsiveness to problem-solvers

Voters faced with two candidates, each coached by a neo-classical economist, also face a hard choice. They often appear apathetic and take a third choice, staying home. However, history denies that voters are intrinsically apathetic. They have gotten turned on by candidates who try to lead up and away from dismal trade-offs.

In 1980 it was Ronald Reagan. Instead of the dismal Phillips Curve (“choose inflation or unemployment”) he offered the happy Laffer Curve: lower tax rates would lead to higher supplies, higher revenues, and lower deficits, he promised. Lowering taxes, said Laffer, would eliminate the “wedge effect.” He often cited Henry George in support of his position. Thus he would unleash supply, and collect more taxes while applying lower tax rates. The voters were sick of 2nd-generation Keynesians who had been reduced to preaching austerity, so they were game (if not wise) to buy into Reaganomics as advertised.

Unfortunately, the Laffer Curve turned out to be wildly overoptimistic, and Reaganomics partly fraudulent and hypocritical in application. The voters again tuned out and seemed apathetic. They are not saying, however, they don’t care. They are saying “come back when you have something better, mean what you say, and deliver what you promise.”

From 1936-70 it was Keynes and his apostles, who had a long run with the voters, in spite of virulent critics. Keynes’s winning political formula was that consumption and capital formation are not alternatives to be traded off, but complements, reinforcing one another. Raise wages, he said, raise private and public consumer spending, and get more capital formation as a happy by-product. “We can have it all,” he said; they called it “the economics of abundance.” Who wouldn’t prefer that to long-faced moralizers preaching we must suffer for the prodigalities of the past, or for the sake of a remote and uncertain future? Even puritans learned better as children from Longfellow’s “Psalm of Life.”

When the theory of the propensity to consume, and the multiplier, lost their charm, and some strong trade unions (like Hoffa’s Teamsters) showed their nastier side, the American voters tuned in to JFK and “business Keynesianism” in which the emphasis turned to fostering new investing. Keynes had been shrewd enough to cast his theories to accommodate either emphasis. Here the formula was to raise the “marginal efficiency of capital” (today we say the marginal rate of return) after taxes by giving preferential tax treatment to new investing, keeping tax rates high on income from old assets like land. It was a species of Georgism, applied via the Federal income tax. The key devices were fast write off for new capital, and the investment tax credit.

There was no talk or thought, however, of enriching capitalists by impoverishing workers. The promise was to enrich capitalists and workers together, as higher investing raised aggregate demand for labor and its products through the “multiplier” effect.

In time that happy glow of mutuality turned to ashes. After JFK, with his influential economist Walter Heller, the flame burned low; later leaders stumbled in the dark. They relied too simple-mindedly on demand management through fiscal and monetary policy, carrying them well beyond their power to stimulate supply. Thus they lurched into Stagflation: double-digit inflation and recession conjoined. They blamed the war, then the Arabs. They scolded the public, and they called for sacrifices, as leaders always do when they lack ideas. “You must mature and face the facts of life,” they lectured. “There is no way to stop inflation except unemployment. Whichever evil you choose, don’t blame us, we told you so.” Faced with that, the voters exercised a third choice: they retired the patrons of those new dismal scientists.

Before Keynes there was another great reconciler, Henry George. In 1879, George electrified the world by identifying a cause of the boom/slump cycle, identifying a cause of inadequate demand for labor, and, best of all, following through with a plausible, practicable remedy. Like Keynes and Laffer after him, he turned people on by saying “Forget the bitter trade-offs; we can have it all.”

George came out of a raw, naive new colony, California, as a scrappy marginal journalist. Yet his ideas exploded through the sophisticated metropolitan world as though into a vacuum. His book sales were in the millions. Seven short years after publishing Progress and Poverty in remote California he nearly took over as Mayor of New York City, the financial and intellectual capital of the nation. He thumped also-ran Theodore Roosevelt, and lost to the Tammany candidate (Abram S. Hewitt) only by being counted out. Three more years and he was a major influence in sophisticated Britain. In 1889, incredibly, he became “adviser and field-general in land reform strategy” to the Radical wing of the Liberal Party in Britain, where he was not even a citizen. It also happened that when Chamberlain bowed out, the Radical wing became the Liberal Party. It adopted a land-tax plank after 1891 (The “famous Newcastle Programme”), and came to carry George’s (muted) policies forward under successive Liberal Governments of Campbell-Bannerman, Asquith, and Lloyd George.

How could a marginal man come out of nowhere and make such an impact? The economic gurus of the day, even as today, were in a scolding mode, blaming unemployment on faulty character traits and genes, and demanding austerity. They were not intellectually armed to refute him or befuddle his listeners. He had studied the classical economists, and used their tools to dissect the system. Neo-classical economics arose in part to fill the void, to squeeze out such radical notions, and be sure nothing like the Georgist phenomenon could recur.

Again, are we not imputing too much weight to a minor figure? We are told that Georgism withered away quietly with its founder in 1897. That, however, is warped history. One of the great derelictions of American historians is to have neglected the single-tax movement, 1901-24. It is also a warped view of “The Single Tax” as a discrete, millennial change, a quantum leap away from life as we know it (Gaffney, 1976). Pure Georgism never “took over whole hog,” but no single philosophy ever does. Modified Georgism, melded into the Progressive Movement, helped run the USA for 17 years, 1902-19, working through both major political parties.

At the local level, it continued on through the early 1920s. Local property taxation was modified on Georgist lines even as it rose in absolute terms. The first Federal income tax law was drafted by a Georgist (Congressman Warren Worth Bailey of Johnstown, Pennsylvania) with Georgist goals uppermost. Real concessions were made: the politicians heard the voters. Historians of the Populist Party and movement often note that its ideas succeeded even though the Party failed, because its ideas were co opted by major parties. Georgism was a strand of American populism, later wrapped into Progressivism.

Consider, for example, that in 1913 Wm. S. U’Ren, “Father of the Initiative and Referendum,” created this system of direct democracy for the express purpose of pushing single-tax initiatives in Oregon. According to U’Ren, another by-product of the single-tax campaigns in Oregon was the 1910 “adoption of the first Presidential Primary Law, which was quickly imitated by so many other States that (Woodrow) Wilson’s nomination and election over Taft was made possible” To that we may add that another “Father of the Direct Primary,” George L. Record of New Jersey, was a mentor of Woodrow Wilson and an earnest Georgist who had gotten railroad lands uptaxed to the great benefit of public schools in New Jersey, and to the impoverishment of special interest election funds.

“… it was the passage of these great election reforms in the Wilson Administration (in New Jersey) that led … (to) winning the Bryan support and the Democratic nomination for President”. That helps explain the gratitude of President Wilson, who included single-taxers in his Cabinet (Newton D. Baker, Louis F. Post, Franklin K. Lane, and William B. Wilson), and worked with single-tax Congressmen like Henry George, Jr., and Warren Worth Bailey.

Consider that in 1916 a “pure single-tax” initiative won 31% of the votes in California. Even while “losing,” such campaigns raised consciousness of the issue to a high degree, such that assessors were focusing more attention on land. Thus, in California, 1917, tax valuers focused on land value so much that it constituted 72% of the assessment roll for property taxation – a much higher fraction than today. Joseph Fels, an idealistic manufacturer, was throwing millions into such campaigns in several states, having earlier thrown himself and his fortune into the English land tax campaign that brought on the Parliamentary revolution of 1909.

Consider that there was a single-tax party, the Commonwealth Land Party. In 1920 its Presidential candidate was Carrie Chapman Catt, fresh from leading her successful campaign for the 19th Amendment, and just before founding the League of Women Voters. In 1924 its Presidential candidate was William J. Wallace of New Jersey, with John C. Lincoln, brilliant Cleveland industrialist, for Vice-president. In 1919 Georgists began working through the Manufacturers and Merchants Federal Tax League to sponsor a federal land tax, the Ralston-Nolan Bill. Drafted by Judge Jackson H. Ralston, it would impose a “1% excise tax on the privilege of holding lands, natural resources and public franchises valued at more than $10,000, after deducting all improvements” In 1924 Congressman Oscar E. Keller of Minnesota reintroduced it (H.R. 5733). In spite of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover, Progressivism still lived in Congress. In 1923, for the first and last time, income tax returns were made public, giving valuable data-ammunition to land taxers.

Consider that in 1934 Upton Sinclair, so-called “socialist,” almost became Governor of California on a modified Georgist platform. Two years later, Jackson H. Ralston, by then a Stanford Law Professor, led another California Initiative campaign to focus the property tax on land values. Norman Thomas, perennial Socialist candidate for President of the U.S., kept a land tax plank in his platform. Daniel Hoan, the “socialist” Mayor of America’s model city, Milwaukee, had his tax assessor focus on upvaluing land. Hoan distributed land value maps to the Milwaukee public, to raise their consciousness of the issue.

Historian Eric Goldman (1956) found George to have inspired most of the major reformers of the early 20th Century. “… no other book came anywhere near comparable influence, and I would like to add this word of tribute to a volume which magically catalyzed the best yearnings of our grandfathers and fathers”. Raymond Moley wrote, “George … touched almost all of the corrective influences which were the result of the Progressive movement. The restriction of monopoly, more democratic political machinery, municipal reform, the elimination of privilege in railroads, the regulation of public utilities, and the improvement of labor laws and working conditions – all were … accelerated by George”.

Consider that most American states and Canadian provinces required separate valuations of land, for tax purposes. Professional valuers, responding to the general interest, were routinely valuing land separately from buildings, and developing workable techniques to handle the occasional tricky case. Valuation anticipates taxation. Lawson Purdy, one of those valuers, was Tax Commissioner of the City of New York, a founder of and power in the National Tax Association, a campaigner for George in the 1897 race, and a leader of the Manhattan Single Tax Club. Under this kind of influence, New York City kept its subway fares down to 5 cents, paying for most of the cost from taxes on the benefitted lands, It also exempted new residential structures from the property tax for ten years, 1924-34.

Consider that Wright Act Irrigation Districts were spreading fast throughout rural California, using Georgist land taxes to finance irrigation works. The Wright Act dated from 1887, and sputtered along fitfully until in 1909 the California Legislature amended the enabling legislation to limit the assessment in all new districts to the land value only. It also let old districts do so by local option. The old districts soon did: Modesto in 1911, Turlock in 1915. This was Georgism getting its “second wind,” so to speak. Beyond much question, the idea was identified with George. The legislative leader, L.L. Dennett of Modesto, got the idea from his father, an old neighbor of Henry George in San Francisco.

In 1917, rural Georgism got a third wind: the California Legislature made it mandatory for all Districts to exempt improvements. They then grew to include over four million acres by 1927, and to dominate American agriculture in their specialty crops. They built the highest dam in the world at that time (Don Pedro, on the Tuolumne River in the Sierra Nevada), financing it 100% from local land taxes. Albert Henley, a lawyer who crafted the modified District that serves metropolitan San Jose, evaluated them thus: “The discovery of the legal formula of these organizations was of infinitely greater value to California than the discovery of gold a generation before. They are an extraordinarily potent engine for the creation of wealth”. They catapulted California into being the top-producing farm state in the Union, using land that was previously desert or range. They made California a generator of farm jobs and homes, while other states were destroying them by latifundiazation.

If this is a “minor” phenomenon it is because the neglect of historians and economists has made it so. One searches in vain through academic books and journals on farm economics for recognition of this, the most spectacularly successful story of farm economic development in history. What references there are consist of precautionary cluckings focused on attendant errors and failures. “Economic development” theorists neglect it altogether, as though California’s commercial farming had sprung full blown from a corporate office, with no grass roots basis, and no development period. It is as though the clerisy were in conspiracy against the demos, under some Trappist oath against disclosing what groups of small people achieved through community action, and through the judicious application of the pro-incentive power of taxing land values.

There is a common defeatist notion that “farmers” are implacably against land taxation. The California experience seems to belie it. In other states, also, The Grange and the Farmers’ Union were pushing for focusing the property tax on land during the ‘teens. In Minnesota, the Dakotas, and the Prairie Provinces the Non-Partisan League became a major power in state and local politics, electing a Governor of North Dakota and swaying many elections. North Dakota exempted farm capital from the county property tax, taxing land only. The spirit of Prairie Populism straddled the 49th parallel (the international boundary), radicalizing politics in rural Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia, all of which were focusing their property taxes on land in this period.

George’s ideas were carried worldwide by such towering figures as David Lloyd George in England, Leo Tolstoy and Alexandr Kerensky in Russia, Sun Yat-sen in China, hundreds of local and state, and a few powerful national politicians in both Canada and the USA, Billy Hughes in Australia, Rolland O’Regan in New Zealand, Chaim Weizmann in Palestine, Francisco Madero in Mexico, and many others in Denmark, South Africa, and around the world. In England, Lloyd George’s budget speech of 1909 reads in part as though written by Henry George himself. Some of Winston Churchill’s speeches were written by Georgist ghosts.

Thus, to the rent-taker, the typical college trustee or regent, George’s ideas remained a real and present danger over several decades: the very decades when neo-classical economics was spreading through the academic clerisy. With the development of direct democracy, open primaries, the secret ballot, direct election of US Senators, the Initiative, Referendum, and Recall, and the like, crude vote-buying such as prevailed in the late 19th Century would no longer dominate the electorate. Mind-control became the urgent need; NCE was the tool.

George’s ideas and the allied Progressive Movement fell, not from failure to deliver, but to the Great Marathon Red Scare that has dominated much of the world from 1919 to 1989. This panic marshalled and energized rent-takers everywhere; by confusion, some of it deliberate, its victims included Georgists. It inhibited them until their message lost its vigor and excitement and became just a minor local tax reform. Its leaders have moved to the trivial center, downplaying George’s grand goals for full employment, catering to the practical but small and prosaic advantages of median homeowners at the local level. Now, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, Progressive ideas might very well pick up again where the original Movement was aborted.

Henry George as reconciler and problem-solver

Let us itemize the several constructive reconciliations in George’s reform proposal. This will explain its wide potential appeal, hence its ongoing threat to embedded rent-takers with a stake in unearned wealth. It will explain why they had neo-classical economists working so hard to put this genie back in the bottle.

1. George reconciled common land rights with private tenure, free markets, and modern capitalism. He would compensate those dispossessed and made landless by the spread and strengthening of what is now called “European” land tenure, whose benefits he took as given and obvious. He would also compensate those driven out of business by the triumph of economies of scale, whose power he acknowledged and even overestimated. He proposed doing so through the tax system, by focusing taxes on the economic rent of land. This would compensate the dispossessed in three ways.

a. Those who got the upper hand by securing land tenures would support public services, so wages and commerce and capital formation could go untaxed.

b. To pay the taxes, landowners would have to use the land by hiring workers (or selling to owner-operators and owner-residents). This would raise demand for labor; labor spending would raise demand for final products.

c. To pay the workers, landowners would have to produce and sell goods, raising supply and precluding inflation. Needed capital would come to their aid by virtue of its being untaxed.

Thus, George would cut the Gordian knot of modern dilemma-bound economics by raising demand, raising supply, raising incentives, improving equity, freeing up the market, supporting government, fostering capital formation, and paying public debts, all in one simple stroke. It’s quite a stroke, enough to leave one breathless. In practice, landowners faced with high land taxes often choose another, even better, course than hiring more workers: they sell the land to the workers, creating an economy and society of small entrepreneurs. This writer has documented a strong relationship between high property tax rates, deconcentration of farmland, and intensity of land use (Gaffney, 1992).

2. George’s proposal lets us lower taxes on labor without raising taxes on capital. Indeed, it lets us lower taxes on both labor and capital at once, and without lowering public revenues.

3. Georgist tax policy reconciles equity and efficiency. Taxing land is progressive because the ownership of land is so highly concentrated among the most wealthy, and because the tax may not be shifted. It is efficient because it is neutral among rival land-use options: the tax is fixed, regardless of land use. This is one favorable point on which many modern economists actually agree, although they keep struggling against it.

George showed that a tax can be progressive and pro-incentive at the same time. Think of it! An army of neo-classicalists preach dourly we must sacrifice equity and social justice on the altar of “efficiency.” They need that thought to stifle the demand for social justice that runs like a thread through The Bible, The Koran, and other great religious works. George cut that Gordian knot, and so he had to be put down.

The only shifting of a land tax is negative. By negative shifting I mean that the supply-side effects of taxing land will raise supplies of goods and services, and raise the demand for labor, thus raising the bargaining power of median people in the marketplace, both as consumers and workers. This effect makes the tax doubly progressive: it undercuts the holdout power and bargaining power of landowners vis-a-vis workers, and also vis-a-vis new investors in real capital. This effect also makes the land tax doubly efficient.

4. A state, provincial, or local government can finance generous public services without driving away business or population. The formula is simple: tax land, which cannot migrate, instead of capital and people, which can. By eliminating the destructive “Wedge Effect,” the land tax lets us support schools and parks and libraries and water purification and police and fire protection, etc., as generously as you please, without suppressing or distorting useful work, and without taxing investors in real capital.

5. Georgist tax policy contains urban sprawl, and its heavy associated costs, without overriding market decisions or consumer preferences, simply by making the market work better. Land values are the product of demand for location; they are marked by continuity in space. That shows quite simply that people demand compact settlement and centrality. A well-oiled land market will give it to them.

6. Georgist tax policy makes jobs without inflation, and without deficits. “Fiscal stimulus,” in the shallow modern usage, is a euphemism for running deficits. George’s proposed land tax might be called, rather, “true fiscal stimulus.” It stimulates demand for labor by promoting hiring; it precludes inflation as the labor produces goods to match the new demand. It precludes deficits because it raises revenue. That is its peculiar reconciliatory genius: it stimulates private work and investing in the very process of raising revenue. It is the only tax of any serious revenue potential that does not bear down on and suppress production and exchange. As I said, George takes two problems and composes them into one solution.

7. George’s land tax lets a polity attract people and capital en masse, without diluting its resource base. This is by virtue of synergy, the ultimate rationale for Chamber-of-Commerce boosterism. Urban economists like William Alonso have illustrated the power of such synergy by showing that bigger cities have more land value per head than smaller ones. (Land value is the resource base of a city.) Urbanists like Jane Jacobs and Holly Whyte have written on the intimate details of how this works on the streets. Julian Simon (The Ultimate Resource) philosophizes on the power of creative thought generated when people associate freely and closely in large numbers. Henry George made the same points in 1879.

8. Georgist policies let us conserve ecology and environment while also making jobs, by abating sprawl. It is a matter of focusing human activity on the good lands, thus meeting demands there and relieving pressure to invade lands now wild that are marginal for human needs. Urban sprawl is the kind of sprawl most publicized, but there is analogous sprawl in agriculture, forestry, mining, recreation, and other land uses and industries.

9. Georgist policies let us strengthen public revenues while in the same process promoting economy in government.

Anti-governmentalists often identify any tax policy with public extravagance. Georgist tax policy, on the contrary, saves public funds in many ways. By making jobs it lowers welfare costs, unemployment compensation, doles, aid to families with dependent children, and all that. It lowers jail and police costs, and all the enormous private expenditures, precautions, and deprivations now taken to guard against theft and other crime. Idle hands are not just wasted, they steal and destroy.

Ultimately, Georgist policy saves the cost of civil disturbances and insurrections, and/or the cost of putting them down. In 1992 large parts of Los Angeles were torched, for the second time in a generation, pretty much as foreboded by Henry George in Progress and Poverty. Forestalling such colossal waste and barbarism is much more than merely a “free lunch.”

George’s program would abort other, less obvious wastes in government. It obviates much of the huge public cost now incurred to reach, develop, and safeguard lands that should be left in their natural submarginal condition. Today, people occupy flood plains and require levees, flood control dams, and periodic rescue and recovery spending. Others scatter their homes through highly flammable steep brushlands calling for expensive fire-fighting equipment and personnel, and raising everyone’s fire insurance premiums. Others build on fault lines; still others in the deserts, calling for expensive water imports. Generically, people now scatter their homes and industries over hundreds of square miles in the “exurbs,” or urban sprawl areas, imposing huge public costs for linking the scattered pieces with the center, and with each other.

This wasteful, extravagant territorial overexpansion results from two pressures working together. One force is that of land speculators manipulating politics seeking public funds to upgrade their low-grade lands so they may peddle them at higher prices. The other force is that of landless people seeking land for homes, and jobs, and public funds for “make-work” projects.

Both these forces wither away when we tax land value and downtax wages and capital. This moves good land into full use, meeting the demand for land by using land that is good by Nature, without high development costs. It also makes legitimate jobs, abating the pressure for “make-work” spending. Above all, it takes the private gain out of upvaluing marginal land at public cost. Such lands, if upvalued by public spending, will then have to pay for their own development through higher taxes.

Those nine compelling features of George’s program should be enough to persuade one that it had the potentiality of becoming very popular. Its premise, however, was socializing land rents through taxation. Its very strengths were its undoing, then, by evoking a powerful, intransigent, wealthy counterforce.