Jack Delano Colored drivers entrance, U.S. 1, NY Avenue, Washington, DC 1940

Not sure that’s what I get from the graph.

• The Absolute Dominance Of The US Economy, In One Chart (MW)

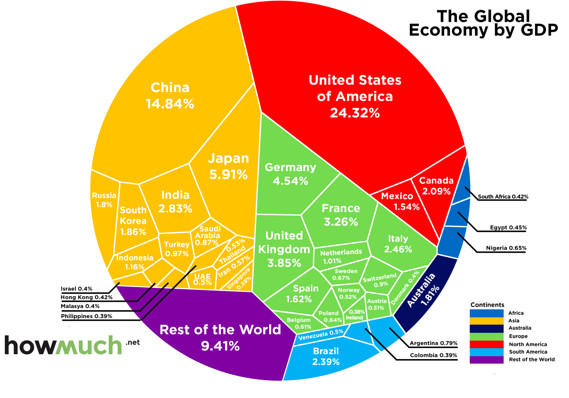

Despite the bleak picture painted by President Donald Trump of the U.S. as a country in disarray, America’s status as an economic superpower is still very much intact, even as China steadily closes the gap. The U.S. economy, as measured by GDP, is by far the largest in the world at $18.04 trillion. China, the closest thing the U.S. has for a competitor, is No. 2 with a GDP of $11 trillion, while Japan is a distant third with $4.38 trillion. As the chart by HowMuch.net illustrates, the U.S. accounts for about a quarter of the global economy, nearly 10 percentage points more than China’s 14.84%. Put another way, the U.S. economy is roughly equivalent to the combined GDPs of the eight next-biggest countries after China — Japan, Germany, the U.K., France, India, Italy, Brazil and Canada.

However, the narrative shifts when countries are grouped by geography, with Asia clearly in the lead. The region, denoted in yellow in the chart, contributed 33.84% to the global GDP. “Asia’s economic center of gravity is in the east, with China, Japan and South Korea together generating almost as much GDP as the U.S.,” said Raul Amoros at HowMuch.net. North America follows Asia at 27.95%, and Europe trails at 21.37%. The three blocs combined represent about 83% of the world’s economic activity. The chart also highlights the chasm between wealthy and poor countries. South America’s four largest economies — Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela and Colombia — only add up to 4% of the global GDP, while Africa’s three biggest — South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria — account for around 1.5%.

I picked the last bit of the article.

• Trump Scorns the IMF’s Globalism, and Now He Gets to Vote on It

The IMF has already survived one major mission-change. It’s known today as the lender of last resort to countries facing balance-of-payments crises. But in its first three decades, the Fund managed the world’s currency order. That was the role assigned at Bretton Woods in 1944, when the IMF and World Bank were set up. Forty-five nations attended the summit, but two men dominated it: John Maynard Keynes and America’s Harry Dexter White. From the back of her car in Uganda, Lagarde calls them the “founding fathers.” Their goal was to avoid a repeat of the 1930s, when competitive devaluations and tariff wars led to the collapse of world trade. Keynes wanted the IMF to act as a central bank of central banks, denominating their accounts in a new global currency. It would let members devalue or borrow with relative ease. Both creditors and debtors would pay interest on their holdings, discouraging large trade surpluses as well as deficits.

White’s plan was more creditor-friendly, reflecting the U.S. position as world lender. There would be no new currency: IMF members would tie their money to the dollar. They couldn’t devalue without consulting the Fund, and were only supposed to borrow short-term to close balance-of-payments gaps. “The British wanted an automatic source of credit, the Americans a financial policeman,” wrote Keynes’s biographer Robert Skidelsky. The English economist was one of the 20th century’s sharpest thinkers, but it was the U.S. Treasury official who got his way. The system turned out to have a flaw: It depended on the supply of U.S. dollars backed by gold. That link came under pressure as America, financing social programs at home and war in Vietnam, slipped into persistent deficit. In 1971, President Richard Nixon took the dollar off the gold standard, ending phase one at the IMF.

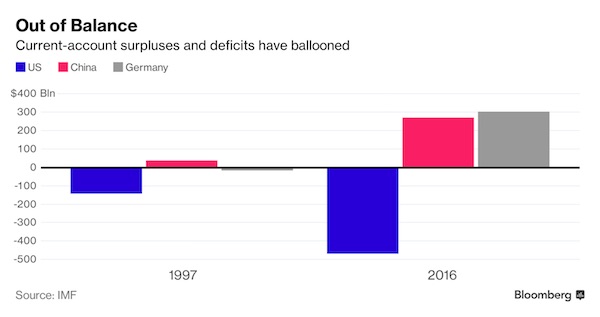

Today there’s a patchwork of floating rates, pegs and currency unions like the euro. It’s not working to everyone’s satisfaction – notably Trump’s. His team has called out several countries, from China to Germany, for gaming the system. Money courses around that system on a scale that would have been unimaginable at Bretton Woods. Massive trade imbalances built up. The dollar remains central. The risks were laid bare in 2008, when a collapsed U.S. housing bubble led to world recession. Since then, some financial leaders – among them the governor of the People’s Bank of China, Zhou Xiaochuan, and his U.K. counterpart Mark Carney – have gently hinted that something more like Keynes’s plan might be in order, to reduce the world’s dollar dependency.

Lagarde doesn’t see that happening on her watch. “It didn’t happen in 1944, when the world had destroyed itself,” she said. “I’m not a dreamer.” She argues instead that what the IMF is doing today will remain useful tomorrow. Countries will always be getting in a financial mess. Someone has to clean it up. Ukraine needed money in 2015: without the IMF, “where would the $17.5 billion come from? Whose pocket would it be?”

The curse of the reserve currency. And if you look a bit deeper, any gold-backed currency.

• The Problem with Gold-Backed Currencies (CHS)

There is something intuitively appealing about the idea of a gold-backed currency –money backed by the tangible value of gold, i.e. “the gold standard.” Instead of intrinsically worthless paper money (fiat currency), gold-backed money would have real, enduring value–it would be “hard currency”, i.e. sound money, because it would be convertible to gold itself. Many proponents of sound money identify President Nixon’s ending of the U.S. dollar’s gold standard in 1971 as the cause of the nation’s financial decline. If our currency was still convertible to gold, the thinking goes, the system would never have allowed the vast pile of debt to accumulate. The problem with this line of thinking is that it is disconnected from the real-world mechanisms of capital flows and the way money is created in our financial system.

This article explains why Nixon took the USD off the gold standard: since the U.S. was running trade deficits, all of America’s gold would have been transferred to the exporting nations. America’s gold reserves would have disappeared, leaving nothing to back the dollar. The U.S. Empire Would Have Collapsed Decades Ago If It Didn’t Abandon The Gold Standard. The problem to sound-money proponents is trade deficits: if the U.S. only had trade surpluses, then the gold would not drain away. But Triffin’s Paradox explains why this doesn’t work for a reserve currency: a reserve currency has two distinct sets of users: domestic users and global users. Each has different needs, so there is a built-in conflict between the two sets of users.

Global users of the USD need enormous quantities of dollars to use as reserves, to pay debts denominated in USD and to facilitate international trade. The only way the issuing nation can provide enough currency to meet this global demand is to run large, permanent trade deficits–in effect, “exporting” dollars in exchange for goods and services. This is the paradox: to maintain the “exorbitant privilege” of a reserve currency, a nation must “export” its currency in size; a nation that runs trade surpluses cannot supply the world with enough of its currency to act as a reserve currency.

That is one damning set of numbers.

• What’s So Great About Europe? (BBG)

A woman said that maybe the problem with the European Union – or at least the common currency, the euro – was that it was too advantageous to Germany. “Because we have a common currency, we get an edge in exports,” she said. “I profit from this. Thanks!” “Do you think this is harming our neighbor countries?” Armbruster asked. “Yes, definitely,” she responded. “Germany was always a problem in Europe,” interjected Andre Wilkens, a Berlin-based policy wonk who was one of the evening’s featured speakers but mostly sat and listened. “The EU was formed to solve that problem.” Others got up to say that Europe needed more solidarity, with Germans leading the way. It needed more of a sense of community. More attention needed to be paid to the millions of jobless young people in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

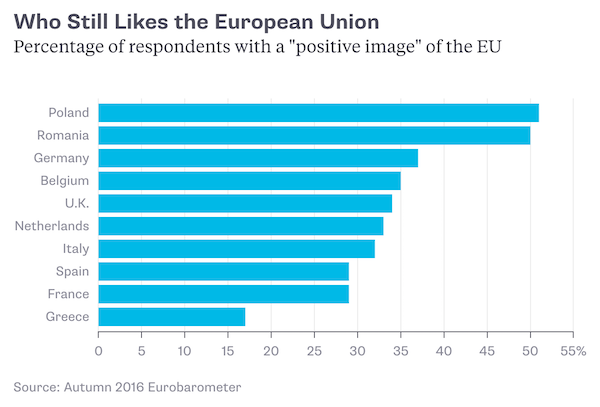

Then things shifted to straight-out Euroenthusiasm. “To be totally honest, I think Europe is super,” said a woman sitting in the front row. Added a man a few rows back: “There are problems that we Germans alone can’t solve.” By working together with the rest of Europe, he went on, Germany had a better shot at fighting climate change and preventing war. It isn’t exactly news that a bunch of people gathered in a theater in downtown Stuttgart support the idea of Europe and even, for the most part, the reality of the European Union. The home of Daimler, Porsche and Robert Bosch is one of the continent’s great economic success stories – and its residents’ political views aren’t necessarily shared by other Germans. On the whole, Germans see the EU in a more positive light than the citizens of most other European countries (I’ve included the 10 most populous EU member countries in the chart below), but they’re still pretty negative about it.

All Italy can do is pretend. And Brussels likes it that way.

• Italy Warned by EU Over High Public Debt With Spillover Risk (BBG)

The European Commission warned that Italy faces excessive economic imbalances as the country’s shaky center-left government struggles to control public debt, boost sluggish growth and mend ailing banks. Troubles including soured bank loans risk spilling into other euro-area countries, the commission said on Wednesday. Italy’s public debt is projected to rise to 133.3% of gross domestic product this year from an estimated 132.8% in 2016. “High government debt and protracted weak productivity dynamics imply risks with cross-border relevance looking forward, in a context of high non-performing loans and unemployment,” the European Union’s executive arm in Brussels said in a set of annual policy recommendations to EU governments. Italy is struggling to maintain government stability amid infighting in the ruling Democratic Party, where some members are pushing for early elections.

The country also faces sluggish GDP growth of 0.9% this year and lingering issues at domestic banks, which are weighed down by €360 billion of bad loans that have eroded profitability, undermined investor confidence and curtailed new lending. “The stock of non-performing loans has only started to stabilize and still weighs on banks’ profits and lending policies, while capitalization needs may emerge in a context of difficult access to equity markets,” the commission said. In May it plans to recommend whether Italy should be subject to a stricter oversight regime – one with fines as a last resort – for failing to keep public debt on a trajectory toward the EU limit of 60% of GDP. The assessment will take into account final economic data for 2016 and Italian government pledges to adopt by the end of April budget-austerity measures worth 0.2% of GDP.

“We have a third world production model of speculators and waiters, with a labour market where the majority of jobs created are temporary and with remunerations of €600, the largest wage decline in living memory..”

• ‘Spain Is Ruined For 50 Years’ (Exp.)

A leading Spanish economist has hit out at the ECB saying “crazy” loans will ruin the lives of the population for the next 50 years.And it is only a matter of time before the Government is forced to default as a debt bubble and low wages effectively forge the worst declines in “living memory”. Leading economist Roberto Centeno, who was an advisor to US president Donald Trump’s election team on hispanic issues, says the country has borrowed €603 billion that it cannot conceivably pay back. And he says Spanish politicians including Minister of Economy Luis de Guindos are “insulting their intelligence” after doing back door deals with the ECB. In a blog post Mr Centeno says there needs to be audits so the country can understand the magnitude of its debt mountain.

He said Spain was “moving steadily towards the suspension of payments which is the result of out of control public waste, financed with the largest debt bubble in our history, supported by the ECB with its crazy policy of zero interest rate expansion and without any supervision.” The expert added the doomed situation will “lead to the ruin of several generations of Spaniards over the next 50 years”. And that current Prime Minister Rajoy has employed 2500 special advisors in his central government as opposed to other leaders. He said: ”Our economic future requires drastic decisions to cut public waste, such as eliminating thousands of useless public companies, thousands of useless advisers, [Prime Minister Mariano] Rajoy has 2,500 in Moncloa, compared to Obama’s 600, Merkel’s 400 or the 250 working for Theresa May.

“There’s disastrous management of Health and Education, the cost of which has skyrocketed 60 per cent since they were transferred to the Autonomous Communities while the quality plummeted.” Mr Centento also said the Government and the European Union’s estimations of GDP are completely wrong and has presented them with figures he claims are accurate. He said the country is currently suffering from a “third world production model”. He added: “We have a third world production model of speculators and waiters, with a labour market where the majority of jobs created are temporary and with remunerations of €600, the largest wage decline in living memory, “And all this was completed with a broken pension system and an insolvent financial system.”

Forecasting an unprecedented shock to the European financial model, Mr Centento is calling for an immediate audit despite a recent revelation that the ECB is failing in its supervisory role over Europe’s banks. He also claimed the Spanish government and European Union leaders have been manipulating figures since 2008. Mr Centento said: “We will require the European Commission and Eurostat to audit and audit the Spanish accounting system for serious accounting discrepancies that may jeopardise stability. “The gigantic debt bubble accumulated by irresponsible governments, and that never ceases to grow, will be the ruin of several generations of Spaniards. “The Bank of Spain’s debt to the Eurosystem is the largest in Europe. “The day that the ECB minimally closes the tap of this type of financing or markets increase their risk aversion, the situation will be unsustainable.”

A feature not a bug.

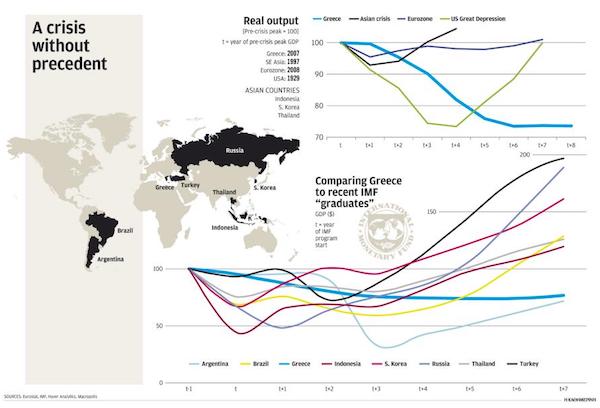

• Why Greece’s Crisis Has Broken All Previous Records (K.)

How unique is the Greek crisis? Two charts tell the tragic tale. The first – from the International Monetary Fund’s recent Article IV report on Greece – compares four major economic crises that took place in the developed world in the last 100 years: the Great Depression in the United States, the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, the eurozone recession and Greece’s long collapse. Greece’s performance is by far the worse. The East Asian countries caught in the hurricane of 1997-8 returned to pre-crisis real GDP within three years. The eurozone needed six years, and today its real GDP is only 2% higher than the pre-crisis high point. The output of the US economy had shrunk by a quarter three years after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, but by 1936 it had recovered to pre-crisis levels. The Greek economy contracted by 26% in real terms between 2007 and 2013, and at the end of 2016 – nine years after the start of its own Great Depression – it remained stuck at the bottom.

The second chart, from the analysis service Macropolis, compares the performance of eight countries that have sought assistance from the IMF since 1997 seven years after the start of their programs. The Fund’s best student was Turkey, which doubled its GDP in real terms between 2000 and 2007. Russia was a close second, largely thanks to growth fueled by climbing oil and gas prices. South Korea comes next, with growth well above 50% from its baseline year, while Indonesia, Brazil and Thailand are hovering around 25%. The only countries which remained below their pre-crisis GDP levels seven years after seeking the Fund’s assistance are Argentina (in the aftermath of the 1998-2002 crisis) and Greece. At its low point, three years into its crisis, Argentina’s dollar-denominated GDP – largely because of the devaluation of the peso after the abolition of convertibility – had fallen by two-thirds compared to pre-crisis highs. At the seven-year mark, Argentina, unlike Greece, was experiencing a robust recovery.

Focusing on the comparison with the Great Depression in the United States, US unemployment peaked in May 1933 at 26%, to be cut by more than half by the end of 1936. In Greece it reached 28% in July 2013, and has since fallen to 23%. The Dow Jones Industrial index lost 85% of its value between August 1929 and May 1932, but it rose fourfold in the three-and-a-half years to the end of 1936 (another 23 years would pass, however, before it got back to pre-crisis levels).

No, it’s not just the EU, or the euro.

“..an economic climate that is normalising low-income families having to live hand to mouth..”

• Millions In UK Are Just One Unpaid Bill Away From The Abyss (G.)

As the cocktail of long-term austerity, rising living costs and a slumping post-Brexit economy hits, what’s really frightening is the crisis that is brewing but is barely being noticed. Look at this week’s finding that one in four families now have less than £95 in savings. That’s staggering, not simply because it gives an insight into how large swaths of families in Britain are clinging on financially in a climate of low wages, cut benefits and high rents, but also because it offers us a warning of how little it will take to push them over the edge. There are now 19 million people in this country living below the minimum income standard (an income required for what the wider public view as “socially acceptable” living standards), according to figures released by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) this month.

Around 8 million of them could be classed as Theresa May’s “just about managing” families: those who can, say, afford to put food on the table and clothe their children but are plagued by financial insecurity. The other 11 million live far below the minimum income standard and are, the JRF warns, “at high risk of falling into severe poverty”. We are entering a period not simply of growing hardship in this country but of what I would call precarious poverty: the sort that isn’t characterised by the traditional image of lifelong, deep-seated deprivation, but which can hit in a matter of days: a broken washing machine, a late child tax credit payment, an injury that leads to time off work. In an economic climate that is normalising low-income families having to live hand to mouth, increasingly, for a whole economic class, one small unexpected cost can trigger a spiral into debt.

And now they’re stuck. This is where it gets risky.

• Oz Reserve Bank Interest Rate Moves Limited By High Debt, House Prices (AbcAu)

Fears of inflating housing bubbles in Sydney and Melbourne are stopping the Reserve Bank from cutting interest rates to boost the economy, the central bank governor conceded today. The stark admission by Reserve Bank governor Phillip Lowe about the RBA’s dilemma comes as soaring house prices in the eastern states have Australians carrying “more debt than they ever have before”. Dr Lowe delivered the reality check at the Australia Canada Economic Leadership Forum, where he said low interest rates made it attractive for borrowers in both countries to invest in real estate, making further rate cuts an undesirable option. “We are trying to balance multiple objectives at the moment,” he said in response to questions after the speech.

“We’d like the economy to grow a bit more quickly and we’d like the unemployment rate to come down a bit more quickly than is currently forecast. “But if we were to try and achieve that through monetary policy it would encourage people to borrow more money and it probably would put more upward pressure on housing prices and, at the moment, I don’t think either of those two things are really in the national interest.” For the moment, it looks like the Reserve Bank feels content — or locked in — to leaving official interest rates on hold at a record low 1.5%. However, Dr Lowe expressed optimism that this level of rates was low enough to spark business investment and stronger economic growth, and therefore there would be no need to lower rates further.

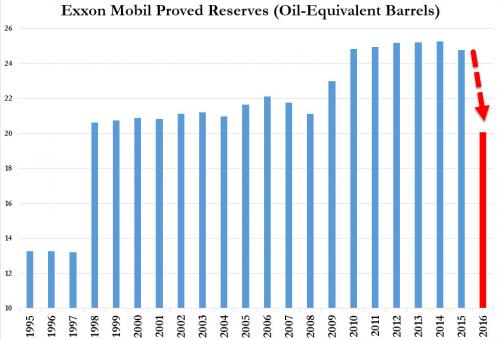

That’s a lot of (not) oil.

• Exxon Wiped A Whopping 19.3% Of Its Oil Reserves Off Its Books In 2016 (Q.)

ExxonMobil has taken a big hit to one of the pillars underlying its decades of braggadocio: its oil reserves. In an announcement today, Exxon said it had written down its proven oil reserves by a massive 19.3%, a stinging reduction to what is a primary measure of any oil company’s value. As of the end of 2016, Exxon had 20 billion barrels in proven reserves, compared with 24.8 billion a year earlier. This includes the erasure of all 3.5 billion barrels of Exxon’s proven oil sands reserves at Canada’s Kearl field. Last year’s low oil prices made it uneconomical to drill at Kearl, which had been at the core of Exxon’s growth strategy. In addition, for the second straight year, Exxon failed to replace all the reserves it pumped—in 2016, it replaced just 65% of its produced reserves. In 2015, it replaced just 67%.

Prior to these years, Exxon had replaced at least 100% of its production every year since 1993. As bad as that was, it was expected: Exxon had signaled that it would write down reserves in 2016, and analysts had expected the company not to replace what it pumped. What wasn’t anticipated was the impact on Exxon’s vaunted longer-term performance. Almost every year, when Exxon announces its earnings, dividend payouts, reserve replacement results—and nearly any other important annual result—it throws in its 10-year record in the respective category to demonstrate its steady, reliable hand on the tiller. This time, bringing up the 10-year record backfired: The replacement failures of the last two years and the 2016 writedown punched a hole in Exxon’s vaunted 10-year reserves replacement average—it plunged to 82% in 2016, from 115% a year earlier.

Simmering conflict.

• Turkish Provocations Test Greek Resolve (K.)

The recent spike in Turkish provocations in the Aegean and incendiary comments emanating from Ankara are aimed at testing Greece’s resolve, according to Greek analysts. In what was seen as its latest transgression, Turkey dispatched its Cesme research vessel to conduct surveys on Wednesday in international waters between the islands of Thasos, Samothrace and Limnos, but within the area of responsibility of the Hellenic Search and Rescue Coordination Center. The night before, Turkish coast guard vessels conducted patrols in the region around the Imia islets. At the same time, the Cyprus talks are being undermined over what Greeks believe is a minor detail – the decision by the Cyprus Parliament for schools to commemorate a 1950 referendum calling for union with Greece.

Greeks say it is an attempt to shift attention from the fundamental issues of the peace talks, namely post-settlement security and guarantees. In response, Athens has pursued the principle of proportionality by countering the presence of Turkish military and coast guard vessels with an equivalent number of Greek ones, while embarking on a diplomatic campaign at international organizations and in major capitals. Analysts also attribute the spike in tension to the Supreme Court’s refusal to extradite the Turkish servicemen that Ankara says were involved in the July coup attempt. But they also note that it serves as a convenient pretext for Turkey to up the nationalistic rhetoric ahead of the April 16 referendum called by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in a bid to expand his powers.

Think maybe rich Europe has slipped Tsipras a few bucks?

• Greece Okays Asylum Requests Of 10,000 Refugees (K.)

At least 10,000 refugees, including around 2,000 minors, are expected to remain in Greece over the coming three years as their asylum applications have been approved. The approved asylum claims account for about a sixth of more than 60,000 migrants who are currently stranded in Greece following the decision last year by a series of Balkan states to close their borders amid a massive influx of refugees from Syria and other war-torn states. The arrival of migrants in Greece has slowed significantly following an agreement between the European Union and Turkey in March last year to crack down on human smuggling across the Aegean.

However, boatloads of migrants continue to arrive on Greek shores from neighboring Turkey. On Wednesday, another 145 migrants arrived on the eastern Aegean island of Chios alone. Authorities attribute the sudden spike in arrivals to the unseasonably good weather. According to the Greek Asylum Service, a total of 1,912 migrants lodged asylum applications in January of this year. Last year, when hundreds of thousands of migrants flooded through Greece toward other parts of Europe, a total of 51,091 people applied for asylum in Greece, compared to 13,195 in 2015, 9,432 in 2014 and 4,814 in 2013.

Home › Forums › Debt Rattle February 23 2017