Dorothea Lange Drought-stricken farm family near Muskogee, OK August 1939

It’s taken some time, but Nicole is back. Here’s her first article in a hopefully productive cycle:

Food insecurity has become a major global issue in recent years, underlying many of the instances of social upheaval around the world. This is both a reflection of the short-term fluctuations in an over-financialized commodity sector and also of the longer-term limits to growth scenario. As an ever greater number of limits are approached, a confluence of factors capable of compounding each other’s impact is created, and this can rapidly reach boiling point.

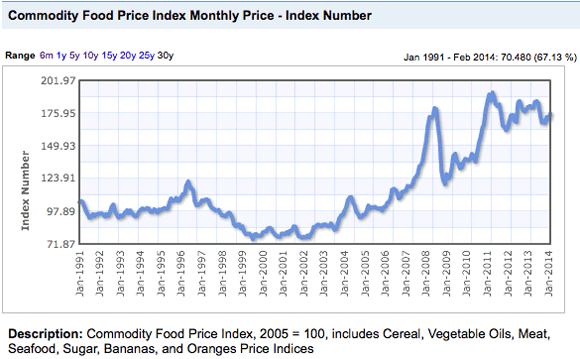

The commodity food price index has risen relentlessly, for a decade, peaking in periods of increasing fear and financial uncertainty. As we are rapidly approaching another such juncture, we can expect the issue to reassert itself with even greater force. Considering that the index demonstrates increasing food prices in nominal terms only, and does not reflect the additional factor of worsening affordability in real terms, it represents a substantial underestimate of the actual situation.

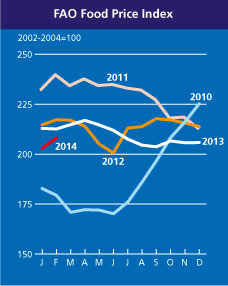

The UN FAO maintains its own food price index, which acts as a predictor of unrest. When it reaches 210, it represents a major red warning flag of a dangerously unstable condition:

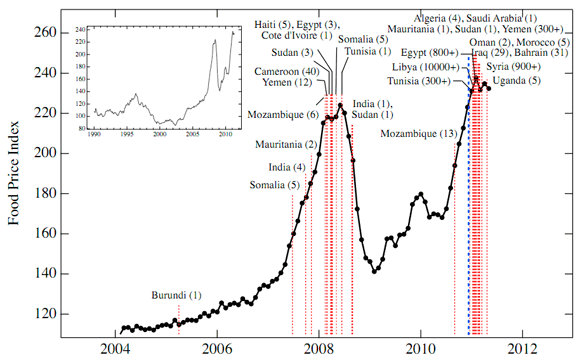

It’s happening in Ukraine, Venezuela, Thailand, Bosnia, Syria, and beyond. Revolutions, unrest, and riots are sweeping the globe. The near-simultaneous eruption of violent protest can seem random and chaotic; inevitable symptoms of an unstable world. But there’s at least one common thread between the disparate nations, cultures, and people in conflict, one element that has demonstrably proven to make these uprisings more likely: high global food prices.

Modern agri-business has a very long list of dependencies on factors which are increasingly under threat, and as these obvious and predictable risks manifest, food insecurity will become a more ever-present condition globally. It is essential that we look to transforming food production, moving away from large scale industrial processes producing pseudo-food in an exceptionally destructive manner. Smaller scale and far saner practices, with far fewer unrealistic dependencies, need to be encouraged, and rapidly, if we are to avoid an extensive food supply crunch in the uncomfortably near future. There is almost nothing capable of having a comparably destructive effect on the fabric of society:

We now know that the fundamental triggers for the Arab spring were unprecedented food price rises. The first sign things were unravelling hit in 2008, when a global rice shortage coincided with dramatic increases in staple food prices, triggering food riots across the middle east, north Africa and south Asia. A month before the fall of the Egyptian and Tunisian regimes, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) reported record high food prices for dairy, meat, sugar and cereals.

Since 2008, global food prices have been consistently higher than in preceding decades, despite wild fluctuations….food price volatility is only a symptom of deeper systemic problems – namely, that the global industrial food system is increasingly unsustainable….The link between intensifying inequality, debt, climate change, fossil fuel dependency and the global food crisis is now undeniable. As population and industrial growth continue, the food crisis will only get worse…..The Arab spring is merely a taste of things to come.

Among the many dependencies of the agribusiness model, a true picture requires the consideration of finance, land ownership concentration, water, energy, climate, trade dependency, soil fertility/carrying capacity, biodiversity, inappropriate regulation and increasing corporate control over the food supply. This article is intended to be an overview of the first risk factor for food shortages – finance.

The world of finance has huge influence on food security, with many factors reinforcing each other. Commodity prices, consumer prices, land required to make a viable return, financial access to land, quota systems, risk management strategies, credit and debt are all vital considerations for farmers. Disruptions in this financial web, which has acted increasingly to trap farming into an over-stretched and highly vulnerable position, can be devastating.

Commodity prices are intimately connected with financial, as the whole commodity sector has been over-financialized, and therefore open to speculation and subjected to the boom and bust dynamics intrinsic to financial markets. Speculative episodes wreak havoc with sectors of the real economy, adding an artificial volatility to prices, on top of natural seasonal fluctuations or price movements due to climatic impacts. They provide ample, and highly profitable, opportunities for the exploitation of basic human needs:

Goldman makes its “food speculation” revenues by setting up and managing commodity funds that invest money from pension funds, insurance companies and wealthy individuals in return for fees and commissions. The firm invented these kinds of funds and continues to dominate the market, together with Barclays and Morgan Stanley. Swiss trading giant Glencore hit the headlines in August when its head of agriculture proclaimed that the US drought will be “good for Glencore”.

Goldman has always shrouded the breakdown of its profits in secrecy, but a WDM commodities derivatives expert has calculated the revenues it believes the bank makes from food speculation through an analysis of its recent results and market information. The bank declined to comment on WDM’s estimate or the impact of speculation on food prices. But Goldman Sachs is known to be advising clients that corn is one of its top trading tips for 2013, after the worst drought in US history whittled stockpiles down to their lowest level since 1974….Since deregulation allowed the creation of the commodity funds that allowed many speculators to invest in agriculture for the first time, institutions such as Goldman have channelled more than $200bn of cash into the area. This investment has coincided with a significant and sustained rise in global food prices.

Commodity prices move with the ebb and flow of liquidity, and with liquidity peaking it is no surprise that prices, including food commodity prices, are also peaking again. This in turn puts pressure on consumer prices, and on increasingly squeezed consumers. In poorer countries, where people spend a huge percentage of what little they have on food, the impact can be intolerable.

As we have explained before, in 2011, in the last price run up:

As we have seen in a number of places, this has been a major ingredient in the development of social unrest. High prices, and fear of both higher prices and actual shortages, can be socially explosive. Rising prices are not themselves inflation, as we have repeatedly explained, but are the result of it. Credit expansions create excess claims to underlying real wealth through the creation of artificial, or virtual, value. They also bring demand forward, increasing pressure on resources for the duration of the expansion period. Extrapolating consumption trends forwards linearly leads to fear of shortages, which encourages market participants to bid up prices speculatively….

….As an expansion develops, one can generally expect increasing upward pressure on commodity prices, thanks to both demand stimulation and latterly the perception that prices can only continue to increase. The resulting crescendo of fear – of impending shortages – is accompanied by the parabolic price rise typical of speculative bubbles, as momentum-chasing creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. At the point where almost everyone with the capacity to do so has jumped on the bandwagon, and all agree that the upward trend is set in stone, a trend change is typically imminent.

Now at another market peak, the same scenario is unfolding again. We see the same combination of unbridled optimism in financial markets, asset bubbles, speculative fervour, and insiders selling out of financial assets to the public, that we have seen at other major tops. In addition, we’re seeing a major movement towards converting financial assets, the vast majority of which constitute excess claims to underlying real wealth, into real assets, such as farmland. This constitutes a grab for a share of the underlying collateral that so inadequately backs the vast quantity of debt in our bubble economy. As we move past the peak, on balance of probabilities in the not too distant future, we are likely once again to see speculative prices retreat with draining liquidity over the remainder of this year, although the grab for real assets is set to continue.

Lower commodity prices are not set to translate, however, into an abatement of the pressure-cooker situation with regard to food security in much of the world. Consumer prices typically lag changes in the money supply, and the commodity price reversals that result from monetary contraction. Consumer prices in volatile regions, already at or near breaking point, would likely remain high in nominal terms for some time. In addition, unrest can sharply raise risk and therefore reduce supply. Liquidity crunch, compounded by the effects of unrest, would also substantially impact people’s ability either to earn an income or to receive benefits. Where both a supply squeeze and a collapse of purchasing power set in as a vicious circle, food affordability can become drastically worse, even if commodity prices, and later consumer prices, decrease. This is the paradox of deflation, as we have explained before:

That is how speculative periods always resolve themselves. We argue, however, that this does not mean commodities will be cheap, even at much lower prices than today, given that the implosion of the wider credit bubble will cause purchasing power to fall faster than price. This means affordability worsening even as prices fall.

The higher prices that have benefited farmers (although not nearly as much as middle men and those higher up the financial food chain), are not set to last. When prices fall, those who depend on the current rate of return are going to be squeezed in their turn, particularly where they are carrying a high level of debt they need to service. Debt for land, equipment, stock, seed, or, in some jurisdictions, market quota, can easily become an unbearable burden.

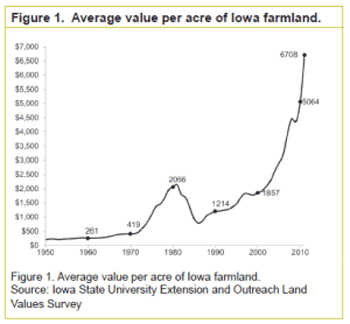

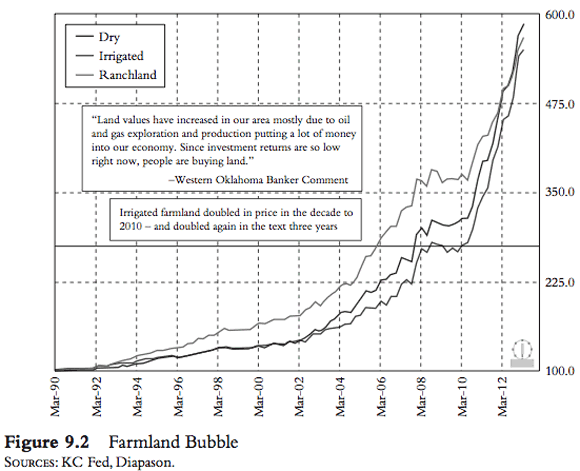

In addition to direct commodity price speculation, the credit expansion and its psychology of commodity shortages has also led to considerable speculation in farmland prices. In many places agricultural land prices have tripled within ten years, demonstrating the exponential rise characteristic of bubbles. This has been part of a general real estate bubble that has also seen much productive land close to cities purchased for lucrative development and taken out of production. The process has increased the pressure on remaining farmland.

There is an increasingly strong perception that farmland prices can never go down, and so are a one way bet for investors. Once this perception becomes entrenched, it is self-reinforcing. Farmland ends up being bought by those looking to make money on a capital gain, rather than those with the knowledge to produce food, or perhaps even interest in doing so. Actual food production is very much a secondary consideration for real estate flippers. Demand for land is artificially stimulated and land values take make a major departure from the fundamental value of their productive capacity. In fact buying land and taking it out of production could accentuate shortages, and drive up both food prices and therefore farmland prices even further, generating an even larger profit. This makes life very much harder for those for whom productive capacity is the important metric.

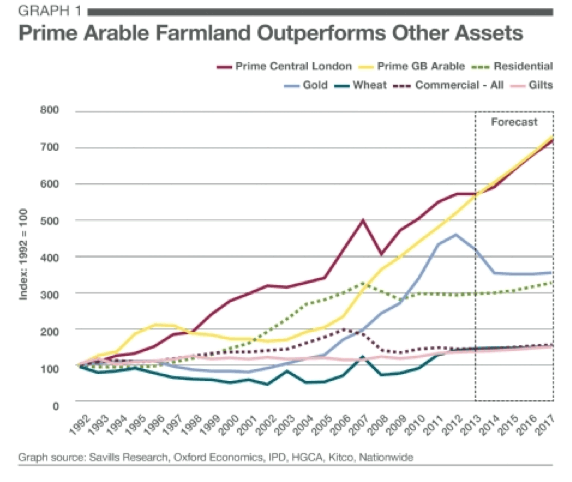

Farmland is currently considered to be one of the best, and safest, investments possible. In the UK for instance, it compares with the top of the bubble prices in central London:

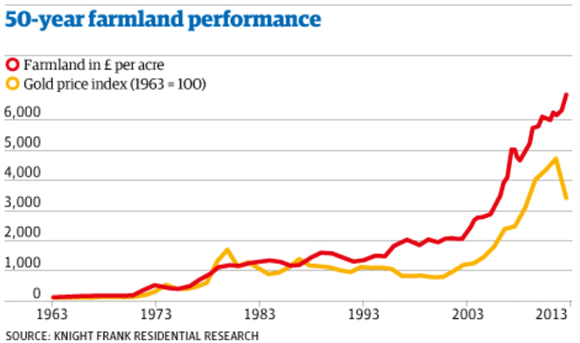

The following article by Britain’s Property Wire shows that rising agricultural land is not just a Canadian or American phenomenon. Farm land prices in the UK hit yet another record high during the first half of 2013 and have now more than trebled in less than a decade. The report says that this exponential growth in prices has been driven by the on going surge in demand from farmers and investors alike. Interest from potential buyers has now seen substantial rises since the end of 2008, and surveyors note that hikes in commodity prices are leading the charge to expand agricultural operations and investors increasingly are seeing land as an economic safe haven.

It has also been a ‘better bet’ than gold in recent years.

For many years it has been growing increasingly difficult to support a family through farming. The young are leaving the land for more lucrative city careers, so the workforce is aging rapidly, with the risk that important knowledge will be lost. Working at the base of the production pyramid is never particularly lucrative (in the absence of distorting subsidy regimes), as one is not in a position to harness and profit from the efforts of others from lower layers. Other careers further up the pyramid, where this is possible, and the personal physical effort required is substantially less, appear far more attractive to the younger generation.

Farmers have been forced to scale up their holdings, buying ever more, and more expensive, land. Land acquisition has created a significant debt burden for many farmers, as do all property bubbles. Farmers have also been seeking ever more expensive equipment necessary to work more land with fewer people. The need for equipment has created a huge dependency on fossil fuel based energy, and with energy prices as volatile as commodity prices, farmers are exposed to many risks they cannot control.

Financial markets have allowed farmers new mechanisms to manage some external risks, at the cost of drawing them more deeply into the financial web. For instance, hedging reduces exposure to price risks, and crop insurance can prevent catastrophic losses. However, both depend on functioning credit markets. It is easy to think that one can buy insulation from risk, but all too often one may buy the right to mange one risk, and yet be exposed to another one was not aware of. The seizing up of credit markets in 2008 revealed some of these risks, particularly in relation to margin debt, and therefore counter-party risk:

Corn, wheat, cotton, soybeans and other commodities have eclipsed record prices this year [2008] as a result of increased biofuel demand, acreage adjustments, production shortfalls, tight carryover stocks, and speculative investment, Welch said. “Many farmers wanting to lock in prices at these historic levels are turning to forward price contracts,” he said. Forward price contracts of a growing crop establish a “price and delivery provision,” Welch said, which transfers price risk from the producer to the writer of the contract. “(This is) usually a grain elevator or cotton merchant,” Welch said. “The elevator or merchant may then transfer this price risk to speculators by hedging in the futures market.”….

Those participating in the futures market must have enough margin money deposited to cover potential losses. The margin is balanced daily and those profits accrued in excess of the margin requirement may be withdrawn. “Any losses that draw the margin account below the minimum maintenance level must be offset by additional deposits to restore the account to its initial balance,” Welch said. Those that fail to bring the account up to the initial required level result in liquidation of the position and the holder of the account must absorb all losses. As a result of rapid escalation of commodity prices, elevators and merchants who wrote forward price contracts are facing losses of “enormous proportions,” Welch said.

“Wheat that was hedged at planting last October for a then all-time record high price of $7 a bushel has incurred margin calls of $6 per bushel or $30,000 per contract.” Forward-contracted corn last fall has increased in price by more than $2 a bushel, he said. “The margin requirement to maintain each of those contracts is now around $10,000,” he said. “For a medium to mid-sized grain elevator to maintain their hedged positions, they have had to deposit millions of dollars in margin money. Add to this the interest cost of funds required to maintain margin requirements and the financial burden of offering and maintaining forward contracts is considerable.”…

….“The impact of severe margin calls on the commercial sector should give growers renewed pause about the margin risks of hedging via selling straight futures,” he said. “Many producers are uncomfortable or unfamiliar or had unprofitable experiences with these marketing alternatives. It’s important that prospective hedgers learn all they can about these markets and understand the risks and rewards before initiating a hedging program.”….

….Commodity organizations representing grain and cotton industries have complained to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission that the markets are no longer working as intended.

Financialization introduces many external parties to the food production equation, and each must manage their own disparate risks. The whole interconnected construct is only as strong as the weakest link, and where over-leverage is concerned, the risk is systemic. Huge losses expose counterparty risk, and that in turn can ruin the perception of the value of ‘insurance’ contracts. It becomes obvious that losing parties cannot pay, and contracts only have value for as long as the promise to pay remains credible. It is possible to destroy a great deal of perceived, or virtual, value very quickly. 2008 was only the opening act in terms of the resolution of the credit bubble of the last 30 years. The majority of the credit contraction still lies ahead of us, so the 2008 dynamic is set to return in a turbo-charged manner over the next few years.

Credit destruction can have a major impact on food production in a short space of time. The failure of hedging or insurance, or both, leaves farmers exposed to price risk or the vagaries of the weather. Farmers who require credit for the purchase of seed may find that it is abruptly no longer available, meaning no planting is possible that year. A financial squeeze may mean that product cannot be sold as demand falls (given that demand is not what one wants, but what one can pay for), or that equipment cannot be repaired for lack of cash flow. Purchasing fuel could become problematic for the same reason.

Once the land price bubble bursts, the market will go illiquid, as real estate always does very quickly under such circumstances. Land prices then have a very long way to fall, and those who purchased their land with leverage at inflated prices may well find themselves sitting on negative equity while in an acute cash flow crisis. When push comes to shove, bankers will call in their loans, essentially imposing a margin call on debtors:

The problem boils down to banking regulations. Bank regulations are more heavily risk-weighting loan assets held by Banks. This causes asset/equity ratios to go out of balance. Banks have two options to correct their ratios, either raising capital or convert loans to cash – as cash assets don’t have a risk weighting discount. Of course the banks would like to start with the riskiest loans, but bad loans can’t be collected, so they are forced to call-in good loans. And there you are, minding your own business with a perfectly performing loan. But the bank needs your cash – not your good loan. Real estate loans are the most commonly called.

That is a recipe for farm foreclosure, as was widespread in the last Great Depression:

All during the war [WWI], Food Administrator Herbert Hoover exhorted farmers in this country to increase production. As the prices realized for their products rose, farmers began to borrow money to buy more acres and new machinery, especially farm tractors since labor costs were sky high. Farm mortgages doubled between 1910 and 1920, from $3.3 billion to $6.7 billion ($74.4 billion today). Then after the war, as a recovering Europe and Russia began to feed themselves (and, in the case of Russia, even finding grain to export), the bottom dropped out. In 1921, the price of wheat dropped to $0.926 per bushel, and heavily indebted farmers couldn’t make the payments on all those new acres and tractors.

As a result, during the “Roaring Twenties” farmers weren’t doing much roaring, but credit was still easy and they limped along, falling further and further behind the rest of the country….Then, in October 1929, the whole financial house of cards that was the U.S. economy collapsed, triggered by the stock market crash….The malaise spread across much of the industrialized world, and soon there was no money to buy the farmer’s products or anything else. Desperate bankers called in their loans, but farmers had no money to pay them and foreclosures and bankruptcy sales became daily events….Some 750,000 farms were lost between 1930 and 1935 through bankruptcy and foreclosure.

We have been here before. This is not the first time finance has been unkind to farming. Where land purchases are concerned, leverage is the key to the pain the bursting of the bubble will cause. For those who have converted financial assets into real assets without leverage, there will be losses in financial terms, but the assets will still remain, and will generally retain productive value over time.

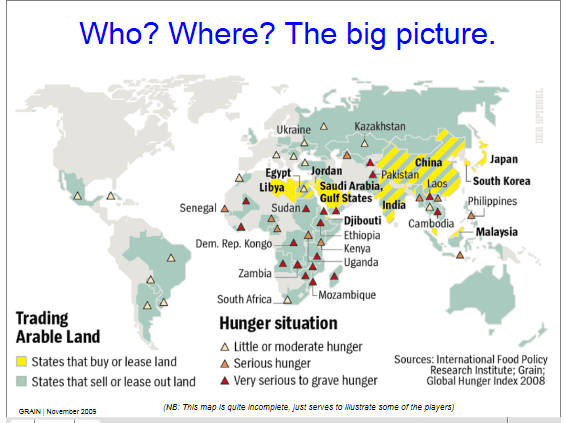

On a broader stage, the effects of finance and the hunt for investment returns on food security are much more immediate and severe. Farmland investment purchases, or land grabs, have increased enormously worldwide. This partly a result of rising food prices and fear of shortages, partly the outcome of a liquidity peak playing out as a farmland bubble, partly an attempt to grab real assets in the face of excess claims to underlying real wealth, and also reflective of wealthy countries with little farmland and large populations seeking outside of their own borders for food security for their own people. For instance, China and Saudi Arabia, among others, have been notable purchasers of external food production capability.

Where investment purchases occur in places where food insecurity, or the looming threat of it, is already present, the impact on the fabric of society is far more immediate than in the developed world. It amounts to an abrupt dislocation rather than a slow squeeze. Produce previously available locally is instead suddenly allocated for export, or, increasingly, land previously used in common by local communities is sold out from under them, denying them access to their means of support. This is becoming a major source of food insecurity, particularly in Africa, and it is being actively encouraged by western agencies such as the World Bank:

In 2009 alone, the World Bank estimates that around the world foreign investors acquired about 56 million hectares of farmland – an area about the size of France – by long-term lease or by purchase. Farmland has become a favourite “new asset” class for private investors; “like gold, only better” according to Capital & Crisis. The World Bank has its own term for the new global land rush. It calls it “agro-investment” and has developed seven voluntary principles to make the land deals “responsible”. Critics of the phenomenon – farmers’ movements, human rights, civil society, women’s and environmental organisations, and many scientists – call it “land grabbing”. They say there is no way that the taking over vast areas of smallholder farmland and transforming it into giant industrial plantations and agribusiness operations can ever be “responsible”. They argue that land grabs are throwing millions of farming families and indigenous peoples off their land….

….More than any other institution or agency, the World Bank Group has been promoting direct foreign investment in Africa, and enabling the farmland rush. Its private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), with its Foreign Investment Advisory Service and its program to Remove Administrative Barriers to Investment, has been working – often behind the scenes – to ensure that African countries reform their land laws and fiscal regimes to make them attractive to foreign investors.

The World Bank Group has funded almost identical investment promotion agencies – “one-stop-shops” – in countries across the continent. It places people in strategic government ministries – even presidential offices – as private sector advisors. The investment promotion agencies are developing and advertising a veritable smorgasbord of incentives not just to attract foreign investment in farmland but also to ensure maximum profits to investors. These include extremely generous tax holidays for 10 or even 30 years, zero per cent duty on imports, and easy access to very large tracts of land, sometimes over 100,000 hectares. Investors may pay just a couple of dollars per hectare per year for the land, and in Mali, sometimes no land rent at all.

The Sierra Leone Investment and Export Promotion Agency, boasts about the extremely low labour rates and flexible labour laws in the country and about other privileges it accords investors – 100 per cent foreign ownership in all sectors, full repatriation of profits, dividends and royalties, no limits on expatriate employees. Such giveaways cast doubt on claims by African governments, and others trying to defend the land deals, that this kind of “agricultural investment” will solve unemployment, generate revenue for cash-strapped governments, reduce the dependence on aid, and bring economic development.

In this race to the bottom, African governments are also encouraged by the World Bank Group to outdo each other when it comes to protecting investors. Each year, it grades African on investor protection in its “Doing Business” report cards, praising countries that move up in the rankings in what an IFC official admits is a “horse race”. This means that low-income and food-deficit African countries, some still struggling to rebuild after long conflicts, such as Sierra Leone and Liberia, find themselves competing with each other to offer foreign investors ever sweeter deals on their arable land, so desperately needed for local food production.

The investment promotion agencies quote figures for the vast amounts of “uncultivated” or under-utilised” land in their countries, often without offering any recent land use studies to back up these figures or a thought for the millions of people who depend on that land for their livelihoods. Nor do they take into consideration the crucial importance of small family farms, which employ more than half the people and produce 80 per cent of the food on the continent….

….Since 2009, in the wake of the food, fuel and financial crises of 2007-2008, the rush for farmland has only accelerated. Recent in-depth research by the US-based Oakland Institute of land deals in seven African countries found that most of the land deals lack transparency, making it almost impossible to calculate their total area. Lack of transparency is a great enabler of corruption. Yet “transparency, good governance, and a proper enabling environment” is one of the seven principles laid out by the World Bank for “responsible agro-investment”. The Oakland Institute found that most of the land deals do not respect any of these principles.

Traditional informal or communal ownership rights are a particular problem, as these are not viewed as valid and are therefore very easy to usurp:

One central problem with land grabbing is that there is no transparency. Investors negotiate with national or local authorities to get access to land, and local communities are not involved in the discussions. The first time that they often learn about it is when the tractors arrive to fence off their land. Similarly, social movements and NGOs often find it difficult to get information.

The impact can be devastating, leaving people abruptly with no options at all:

The “town” chief of the village seemed to be in a state of shock. Sitting on the front porch of his mud and thatch home in Pujehun District in southern Sierra Leone, he struggled to find words that could explain how he had signed away the land that sustained his family and his community. He said he was coerced by his Paramount Chief, told that whether he agreed, or not, his land would still be taken and his small oil palm stand destroyed. He didn’t know the name of the foreign investor nor did he know that it planned to lease up to 35,000 hectares of farmland in the area to establish massive oil palm and rubber plantations. Haltingly, he said that without his land, he might as well take his leave of the village. By that he meant that he was as good as dead.

Investment in third world farmland is a one way street, with benefits accruing to the political and financial centre, very much at the expense of the periphery – local people in marginal locations with already precarious food security. In the rich world hungry for financial yield, expectations are completely unrealistic:

Land grabs, which target 20% profit rates for investors, are all about financial speculation. This is why land grabbing is completely incompatible with ensuring food security: food production can only bring profits of 3-5%. Land grabbing simply enhances the commodification of agriculture whose sole purpose is the over-remuneration of speculative capital.

These are the effects of over-financializing a vital sector of the real economy. Decisions as to land use and scale of operations are made by large players in rich countries for reasons of maximizing investment returns, securing control of vital sectors of the real economy in order to profit from increasing scarcity, and holding on to an asset seen as only going to increase in financial value. Control moves from the hands of local people to large institutional investors, and use reflects their priorities. The interests of the indigenous people, who have been sold out by their own governments, are considered irrelevant, and are ignored until deprivation becomes severe enough to provoke unrest:

The investors are hedge funds, private equity funds (that are attracting even prestigious American universities with their promises of high returns), pension funds, banks, multinational corporations, and sovereign wealth funds seeking to sow capital and grow profits….

….African farmers, left high and dry by their own governments during the decades of austerity programs imposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, do need investment and support. They desperately need decent roads and access to local markets, processing equipment to add value to their own diverse farm produce, storage and drying facilities to prevent post-harvest losses, and basic amenities such as schools and health centres and water wells to improve rural lives, so that farming communities can thrive. But foreign investors are not in business to provide any of these things. They are not in Africa to help impoverished African farmers improve their own farms, or to combat hunger. They are far more likely to destroy the family farm in Africa and aggravate hunger, all in the name of economies of scale, a global corporate food chain, and profits. The same actors – the speculators, bankers, unregulated investors – who have had a hand in inflating food prices and bringing the global economy to its knees are now consolidating control of global food production and of land, to profit from the very crises they provoked.

This process is a continuation of a long-standing, and accelerating, trend towards forced scaling up of land holdings and increasing monetization of farming operations. It began several decades ago with the Green Revolution. This was a programme of agricultural ‘modernization’ involving the introduction of new high-yielding hybrid seed varieties, irrigation infrastructure, western management techniques, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. In the short term, the much higher yields greatly increased food security, but over time a different picture has emerged, and the longer term negative impacts have been considerable.

The hybrid seeds require far more inputs – of water, fertilizers and pesticides and new seeds annually – than did the traditional varieties bred over time to be adapted to the local conditions. These inputs are expensive, which over time caused dependency on western companies as suppliers, and a widespread debt problem for small farmers. Small farmers, who had previously operated largely outside of the monetary economy, or only tenuously connected to it, all too often ended up losing their land as the minimum operational scale to make the inputs affordable increased after they were already hooked into the new system:

As more and more small-scale farmers are unable to compete with the larger farms, the chances that they sell off or mortgage out their land also increases. When the small-scale farmers are no longer able to make their payments, their ownership of the land is taken from them and in some cases the farmers and their families are evicted and thus unemployed. “This effect especially if combined with the eviction of an appreciable number of tenants will generate a growth in both the size and insecurity of the rural landless labor force. Growing numbers of the unemployed undoubtedly will leave the countryside and join the migration to the cities—swelling the urban slums.

Forcing farming from non-monetary subsistence into the monetary economy created greater concentration of land ownership (along with a tremendous loss of valuable biodiversity). The process of globalization has in general forced monetization as far down the operational scale as possible, and has increasingly cut off possibilities for operating viably below that scale. Plugging as many economic activities as possible into the monetary economy allows for surpluses to be efficiently removed via the wealth conveyor system from the periphery to the centre. After all, it is far simpler to collect surpluses in the form of money than in the form of produce. Combined with trade agreements strongly favouring richer countries with agri-business subsidies, the impact on small farmers has been dramatic. For instance, there has been an epidemic of farmer suicides in India – 200,000 between 1997 and 2009. This is clearly a reflection of people being pushed into an untenable situation. When farmers are so insecure, there can be no real food security for the rest of the population either.

The connection between boom and bust psychology, food insecurity and unrest is not always clear from headlines describing current events, but it is increasingly pertinent geopolitically. The impact, long felt in the global periphery, is inexorably moving into stressed areas of the developed world, as wealth concentration increases. Inequality has been deepening in richer countries too, as the base of the pyramid is squeezed ever more tightly in order to sustain the pinnacle in the condition to which it has become accustomed.

Food insecurity is a highly profitable business for those in a position to administer the misery:

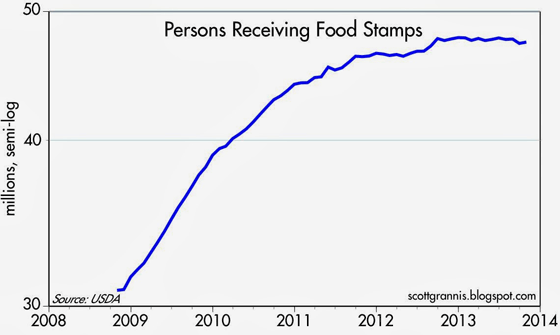

Every time an American signs up for food stamps in one of 23 states, JPMorgan Chase & Co. adds to its revenue stream. That because JPMorgan Chase contracts to operate as the processor of the Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards in those states. JPMorgan earns a fee for each recipient, ranging from 31 cents to $2.30, depending on the state, every month for the term of the contract. JPMorgan’s seven-year Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, the official name for the federal food stamp program) contract with New York state, for example, brought in more than $126 million of revenue to the big bank. Florida has paid JPMorgan more than $90 million since 2007. Pennsylvania’s seven-year contract exceeded $112 million….

….The number of Americans receiving SNAP benefits has more than doubled since 2000, to an astounding 46.6 million people as of 2012, according to government data. That’s nearly 15% of the U.S. population. So it’s no surprise that U.S. government spending on food stamp benefits has grown from $18 billion in 2000 to $85 billion in 2012 – a steep increase that has given JPMorgan a nice boost….And the bank has taken steps to make sure the SNAP program remains a growing source of revenue. JPMorgan’s political donations to the members of House and Senate agricultural committees, the ones with legislative responsibility for the program, soared from just over $82,000 in 2002 to nearly $333,000 as of 2010.

As if profiting from a program designed to help the poor were not bad enough, JPMorgan also makes money directly from the SNAP recipients. The GAI said JPMorgan and the other two primary EBT administrators – a subsidiary of Xerox Corp. called Affiliated Computer Services, and eFunds Corp., a subsidiary of Fidelity National Information Services – make money from food stamp recipients in other ways as well. Purchases made by EBT cards can only be made with special Point of Sale (POS) machines, for which the states also pay JPMorgan a monthly fee. Arizona pays $14.95 per POS machine per month. In addition, any time a SNAP recipient uses an EBT card at an ATM machine outside of JPMorgan’s network, the bank charges a fee, just as it would any other customer. JPMorgan also charges EBT users to replace lost cards, and for customer service calls (New York cardholders, for example, pay 25 cents per call.) All those charges and fees come directly out of the pocket of SNAP recipients – people so poor they need food stamps to make ends meet.

The bust phase of financial boom and bust does not play out as a slow squeeze, but typically as an abrupt dislocation once a critical tipping point has been reached. We have not yet seen this in the developed world, but the risk factors have clearly been well established. Farming is already well into financial overshoot, and also well into energy and ecological overshoot, but that is another story.

Food insecurity is clearly present at the base of the pyramid, and could rapidly shoot upwards over the next very few years. There is therefore a need to underline the urgency for radical change in food production systems. Even if we could expect useful policy reform in this field, which we cannot for reasons of regulatory capture and systemic inertia, among many other factors, the timescale would be far too long to make a difference. The change that is required can only come from the bottom up, though the decentralization of food production at human scale. As we have written before at TAE, scale matters, and decentralization, particularly in advance of system criticality, will be challenging. However, we have no other choice.

Part II of this essay will address the broader issues of food security, including water, energy, climate, soil fertility, and regulation.

Home › Forums › Nicole Foss: Finance and Food Insecurity