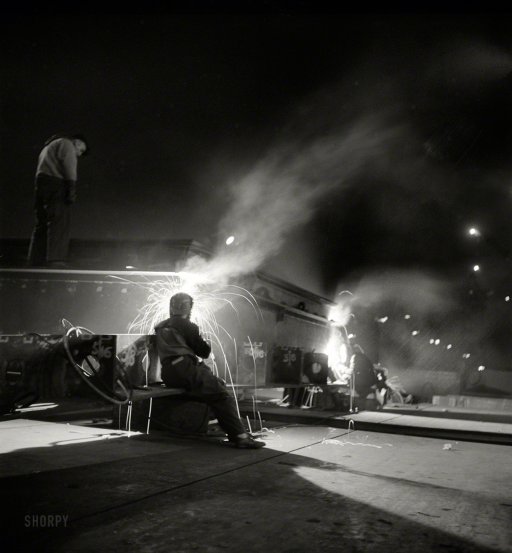

Arthur Siegel Bethlehem-Fairfield shipyards, Baltimore, MD May 1943

A lot of people these days vent their opinions on what’s happening with the Chinese economy, and the opinions are so all over the place they could hardly be more different. Which is interesting, to say the least. Apparently it’s still very hard to understand what does happen ‘over there’.

And I don’t at all mean to suggest that I would know better than Morgan Stanley’s former Asia go-to-man Stephen Roach, or hedge funder Hugh Hendry, or Bob Davis, who just spent 4 years in the country for the Wall Street Journal, or Gwynn Guilford at Quartz, or local Reuters correspondents. It’s just that between them, they disagree so vastly you’d think they’re playing a game with your mind.

Me, personally, I think China’s official economic data should be trusted even less – if possible – than those of most other nations, including Japan, EU+ and the US. And therefore the rate cut last week, and the ones that look to be in the offing soon, constitute neither an act of confidence nor an confident act. China may well already be doing a lot worse than we think.

So where are we right now with all this, what DO we know? The best approach seems to be, as always, to follow the money. Let’s start with Reuters today:

China Ready To Cut Rates Again On Fears Of Deflation

China’s leadership and central bank are ready to cut interest rates again and also loosen lending restrictions, concerned that falling prices could trigger a surge in debt defaults, business failures and job losses, said sources involved in policy-making. Friday’s surprise cut in rates, the first in more than two years, reflects a change of course by Beijing and the central bank, which had persisted with modest stimulus measures before finally deciding last week that a bold monetary policy step was required to stabilize the world’s second-largest economy.

Economic growth has slowed to 7.3% in the third quarter and policymakers feared it was on the verge of dipping below 7% – a rate not seen since the global financial crisis. Producer prices, charged at the factory gate, have been falling for almost three years, piling pressure on manufacturers, and consumer inflation is also weak. “Top leaders have changed their views,” said a senior economist at a government think-tank involved in internal policy discussions.

The economist, who declined to be named, said the People’s Bank of China had shifted its focus toward broad-based stimulus and were open to more rate cuts as well as a cut to the banking industry’s reserve requirement ratio (RRR), which effectively restricts the amount of capital available to fund loans. China cut the RRR for some banks this year but has not announced a banking-wide reduction in the ratio since May 2012. “Further interest rate cuts should be in the pipeline as we have entered into a rate-cut cycle and RRR cuts are also likely,” the think-tank’s economist said.

Friday’s move, which cut one-year benchmark lending rates by 40 basis points to 5.6%, also arose from concerns that local governments are struggling to manage high debt burdens amidst reforms to their funding arrangements, the sources said. Top leaders had been resisting a rate cut, fearing it could fuel debt and property bubbles and dent their reformist credentials, but were eventually swayed by signs of deteriorating growth as the property sector cooled.

This suggests a certain level of control on the part of China, but certainly not a full swagger. And yes, they’re at 5.6%, and so there seems to be a lot of leeway left if you look at the near zero rates we see all over the world.. But then again, China wants, or should we by now say pretends to want, a 7% growth level. The fact that they’re ready to cut more doesn’t bode well for that growth number, even as they pretend to boost growth with those exact same cuts.

We saw China’s largest corporate bankruptcy last week, of the Haixin Iron & Steel Group, and that is not a good sign. China has been borrowing beyond the pale, a process in which the shadow banking system has played a major role, to ‘invest’ in commodities with an eye to much more growth even than the 7% Beijing claims to aim for. The problem with that is that this overbuying has been a substantial part of that same growth number.

And we know the story, certainly after the Qingdao warehouse tale this spring, where nobody could figure out anymore who actually owned what piles of aluminum, copper and iron because they were all used as collateral for multiple loans. In that bleak light, that one of the principal iron and steel companies goes belly up can hardly be seen as a positive message. China may be buying a whole lot less metal. And a whole lot less oil too. Which may drive down global market prices a lot, because everybody’s last hope was China.

Stephen Roach of Morgan Stanley fame, however, think Beijing has it all down. Full control. If they say 7%, 7% it is. Now, I know Roach spent a lot of time over there, but perhaps that was in the days when 10% GDP growth was still a realistic number. And that may not have had much to do with Beijing control.

Now that growth is gone everywhere, other than in stock markets and private banks’ reserves at central banks, where would China get even a 7% number from? And to what extent would Beijing have any control over that at all? Roach has little doubt that whatever number Xi and Li Call will be the correct one:

China Cut Pegs Growth Floor At 7%,: Stephen Roach

After unexpectedly cutting interest rates for the first time in two years, Chinese leaders have revealed their floor for economic growth is around 7%, said Stephen Roach[..] In a surprise announcement Friday, the People’s Bank of China said it was cutting one-year benchmark lending rates by 40 basis points to 5.6%. It also lowered one-year benchmark deposit rates by 25 basis points. [..] The hyperbole about China being an ever-ticking debt bomb stacked with excesses and nonperforming loans is based on emotion rather than empirical data, he said.

Hugh Hendry arrives at a similar conclusion through different means, namely the central bank omnipotence theory. And sure enough, central banks can do a lot, spend a lot, and fake a lot. But if there’s one thing the present global deflation threat tells us they can’t do, it’s to make people spend money. Not in Japan, not in Europe, not stateside, and not in China. It would seem advisable to keep that in mind.

Hugh Hendry: “A Bet Against China Is A Bet Against Central Bank Omnipotence”

Merryn Somerset Webb: But you’re assuming that the correct policy will be followed [in China].

Hugh Hendry: Well, it has been to date. That they haven’t panicked and gone into that crazy splurge in 2009-2011, they haven’t done that. Then the other point with China it’s a bit like the US. It’s had its excess. The problem in the US was it was felt intently with the private banking system which went bankrupt. But, and this is not counter-factual, what if you owned, what if the state is the banking sector? Does it have a Minsky moment? I’d say it doesn’t. So the whole game with Fed QE was to underwrite the collateral values, to keep the credit system moving. So it aimed its fire at mortgage obligations more than Treasuries.

The whole deal with LTROs in Europe has been again when investors at volume banks at 40%-60% discounts to asset volume, the central bank’s coming in and saying, “Actually we’ll buy it from you at full value or something higher. So we are going to endorse the collateral of your assets.” In China it’s the same deal. They’re fiat currency and they can get away with this. So to bet against China or Chinese equities, or the Chinese currency is to bet against the omnipotence of central banks. One day that will be the right trade, just not ready or sure that that is the right trade today.

Gwynn Guilford at Quartz suspects that Beijing if not so much in control as it is freaking out, and that that’s why they’ve cut rates and are publicly suggesting they’ll do it again.

China’s Surprise Rate Cut Shows How Freaked Out The Government Is By The Slowdown

Earlier [this week], the People’s Bank of China slashed the benchmark lending rate by 40 basis points, to 5.6%, and pushed down the 12-month deposit rate 25 basis points, to 2.75%. Few analysts expected this. The PBoC – which, unlike many central banks, is very much controlled by the central government – generally cuts rates only as a last resort to boost growth.

The government has been rigorously using less broad-based ways of lowering borrowing costs (e.g. cutting reserve requirement ratios at small banks, and re-lending to certain sectors). The fact that the government finally cut rates suggests that these more “targeted” measures haven’t succeeded in easing funding costs for Chinese firms. The push that came to shove might have been the grim October data, which showed industrial output, investment, exports, and retail sales all slowing fast.

Those data suggest it will be much harder to get anywhere close to the government’s 2014 target of 7.5% GDP growth, given that the economy grew only 7.3% in the third quarter, its slowest pace in more than five years. But wait. Isn’t the Chinese economy supposed to be losing steam? Yes. The Chinese government has acknowledged many times that in order to introduce the market-based reforms needed to sustain long-term growth and stop piling on more corporate debt, it has to start ceding its control over China’s financial sector.

[..] But clearly, the economy’s not supposed to be decelerating as fast as it is. Tellingly, it’s been more than two years since the central bank last cut rates, when the economic picture darkened abruptly in mid-2012, the critical year that the Hu Jintao administration was to hand over power to Xi Jinping. The all-out push to boost growth that followed made the 2013 boom, but also freighted corporate balance sheets with dangerous levels of debt. But this could only last so long; things started looking ugly again in 2014.[..]

What hasn’t been mentioned yet, and that’s undoubtedly a huge oversight, whether you’re talking about the theoretical Beijing political control over growth numbers, or the nitty gritty of actual numbers in the real economy, is the power, both political and financial, of the Chinese shadow banking industry.

The guys who’ve been making a killing off loans to local officials who couldn’t get state bank loans but were still rewarded for achievements in their constituencies that would have been impossible without loans. Where would China be without shadow banking? What is it today, a third of the economy, half?

And the Xi-Li gang seeks to break its power, for a multitude of reasons. The shadow set-up only works as long as things are great, and the sky’s the limit. When that diminishes, not so much. You can borrow all the way to nowhere when you’re doing great, but when you go broke, all you’re left with is the debt.

That’s the reality a lot of Chinese officials and entrepreneurs find themselves in today. Which is why the next article below says ” .. city officials reminded residents that it is illegal to jump off the tops of buildings ..” They don’t just own money, they own it to the wrong people too. Not that I presume there’s right people to be indebted to in China, but those who volunteer to re-arrange your physical appearance must be last on the list.

Bob Davis spent a few recent years in China for the Wall Street Journal, and he has this to say:

The End of China’s Economic Miracle?

When I arrived, China’s GDP was growing at nearly 10% a year, as it had been for almost 30 years – a feat unmatched in modern economic history. But growth is now decelerating toward 7%. Western business people and international economists in China warn that the government’s GDP statistics are accurate only as an indication of direction, and the direction of the Chinese economy is plainly downward. The big questions are how far and how fast. My own reporting suggests that we are witnessing the end of the Chinese economic miracle.

We are seeing just how much of China’s success depended on a debt-powered housing bubble and corruption-laced spending. The construction crane isn’t necessarily a symbol of economic vitality; it can also be a symbol of an economy run amok. Most of the Chinese cities I visited are ringed by vast, empty apartment complexes whose outlines are visible at night only by the blinking lights on their top floors.

I was particularly aware of this on trips to the so-called third- and fourth-tier cities—the 200 or so cities with populations ranging from 500,000 to several million, which Westerners rarely visit but which account for 70% of China’s residential property sales. From my hotel window in the northeastern Chinese city of Yingkou, for example, I could see empty apartment buildings stretching for miles, with just a handful of cars driving by. It made me think of the aftermath of a neutron-bomb detonation—the structures left standing but no people in sight.

The situation has become so bad in Handan, a steel center about 300 miles south of Beijing, that a middle-aged investor, fearing that a local developer wouldn’t be able to make his promised interest payments, threatened to commit suicide in dramatic fashion last summer. After hearing similar stories of desperation, city officials reminded residents that it is illegal to jump off the tops of buildings, local investors said.

[..] In the late 1990s, the party finally allowed urban Chinese to own their own homes, and the economy soared. People poured their life savings into real estate. Related industries like steel, glass and home electronics grew until real estate accounted for one-fourth of China’s GDP, maybe more.

Debt paid for the boom, including borrowing by governments, developers and all manner of industries. This summer, the IMF noted that over the past 50 years, only four countries have experienced as rapid a buildup of debt as China during the past five years. All four – Brazil, Ireland, Spain and Sweden – faced banking crises within three years of their supercharged credit growth.

[..] China’s immense scale has now become a limitation. As the world’s largest exporter, how much more growth can it count on from trade with the U.S. and especially Europe? [..] Will Mr. Xi’s campaign reverse China’s slowdown or at least limit it? Perhaps. It follows the standard recipe of Chinese reformers: remake the financial system so that it encourages risk-taking, break up monopolies to create a bigger role for private enterprise, rely more on domestic consumption.

But even powerful Chinese leaders have trouble enforcing their will. I reported earlier this year on the government’s plan to handle one straightforward problem: reducing excess steel production in Hebei, the province that surrounds Beijing. Hebei alone produces twice as much crude steel as the U.S., but China no longer needs so much steel, to say nothing of the emissions that darken the skies over Beijing.

It’s hard to say anything definitive about the Chinese economy and the official government numbers, for anyone but the rulers, because those numbers are clad in a murky veil. But what we do know from our experience here in the west is that the murkiness of numbers is invariably used by our ‘leaders’ to make things look better than they are. If anything, it seems reasonable to presume Beijing exaggerates its ‘achievements’ even more than our own clowns.

And in that light, I don’t see how or why the $30 oil I talked about yesterday would be all that far-fetched, given that China has driven most of the world’s growth expectations over the past decade or so, and that it seems to have very little chance of living up to those expectations. Even if for no other reason than because the rest of the world stopped growing.

And that seems to me to be where China’s growth fairy tale has stopped, and must have: ‘consumer spending’ (ugly term) across the world is falling. After all, that’s were all the lowflation and deflation comes from. And central banks can’t force their people to spend. Not in China and not in the west. They only need to look at Japan to see why that is true and how it plays out.

Growth in Japan is gone, and no QE can revive it. In Europe, it’s beyond life support. In the US, things look a little different on the surface, but the US can’t withdraw and do well in the present economic system if Japan and Europe don’t.

And that’s China’s story too. No growth anywhere to be seen, and they’re supposed to have 7%? It’s simply not possible. At least that we know.

Home › Forums › Where Is China On The Map Exactly?