DPC Times Square seen from Broadway 1908

I was reading something yesterday by my highly esteemed fellow writer Charles Hugh Smith that had me first puzzled and then thinking ‘I don’t think so’, in the same vein as Mark Twain’s recently over-quoted quote:

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

I was thinking that was the case with Charles’ article. I was sure it just ain’t so. As for Twain, I’m more partial to another quote of his these days (though it has absolutely nothing to do with the topic:

“Eat a live frog first thing in the morning, and nothing worse will happen to you the rest of the day.”

Told you it had nothing to do with anything.

Charles’ article deals with money supply and the velocity of money. Familiar terms for Automatic Earth readers, though we use them in a slightly different context, that of deflation. In our definition, the interaction between the two (with credit added to money supply) is what defines inflation and deflation, which are mostly -erroneously- defined as rising or falling prices.

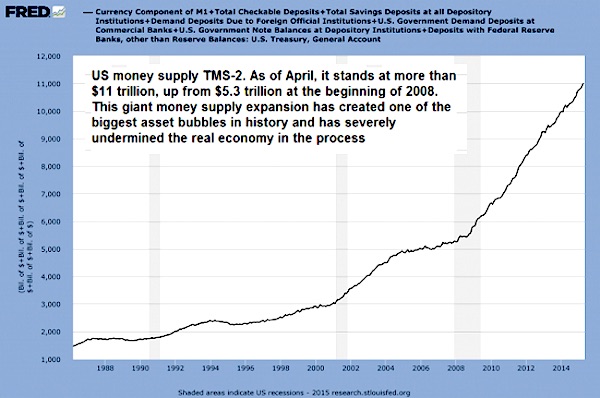

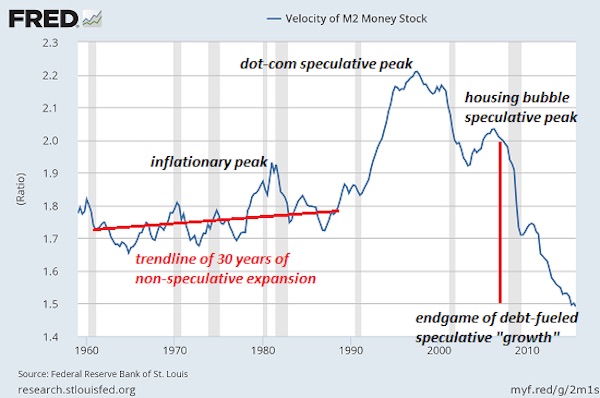

I don’t want to get into the myriad different definitions of ‘money supply’, and for the subject at hand there is no need. The first FRED graph below uses TMS-2 (True Money Supply 2 consists of currency in circulation + checking accounts + sweeps of checking accounts + savings accounts). The second one uses M2 money stock. Not the same thing, but good enough for the sake of the argument.

In his piece, Charles seems to portray the two, money supply and velocity of money, as somehow being two sides of the same coin, but in a whole different way than we do. He thinks that the money supply can drive velocity up or down. And that’s where I think that just ain’t so. I also think he defeats his own thesis as he goes along.

Before going into details, two things: One, he doesn’t mention the term deflation even once, though he shows money velocity has been going off a cliff like a mountain range and a half full of lemmings. I find that curious.

Two, he doesn’t mention consumers in the context. That can’t be right either. 70% of US GDP is consumers. You can’t ignore that. You can’t just look at financial markets, at investors, even though they use up most of the stimulus, and think they are the main factor determining money velocity. Not when they’re less than a third of GDP.

Moreover, and this I think is crucial, the velocity of money talks to you about consumers in a way that the money supply never could.

There may be ‘positive’ reports coming out of the BLS on jobs numbers, but with 94+ million Americans not in the labor force, with the quality of jobs diminishing so fast and so profoundly that the middle class is all but disappearing, and with 40+ million US citizens on foodstamps, the impact of the deteriorating spending power of ‘consumers’ on money velocity had to be so enormous you can’t ignore them.

Simply because if and when people have a lot less to spend, velocity comes down. That there is even the very heart of deflation. Here’s Charles with my comments:

Money Velocity Is Crashing – Here’s Why

The inescapable conclusion is that Fed policies have effectively crashed the velocity of money.

I’ll get back to that, but no, it is not true.

That the velocity of money has been crashing while the money supply has been exploding doesn’t seem to bother the mainstream pundits. There is always a fancy-footwork explanation of why whatever is crashing no longer matters. Take a look at these two charts and tell me money velocity doesn’t matter.

No argument about that from me.

First, here’s money supply: notice how money supply leaped from 2001 to 2008 as the Federal Reserve pumped liquidity and credit into the economy, and then how it exploded higher as the Fed went all in after the Global Financial Meltdown.

Now look at a brief history of the velocity of money. There are various measures of money supply and various interpretations of velocity, but let’s set those quibbles aside and compare money velocity in the “golden era” of the 1950s/1960s and the stagflationary 1970s to the present era from 2008 to 2015-the era of “growth”:

Notice how the velocity of money remained in a mild uptrend during both good times and not so good times. The inflationary peak of 1979-1982 (Treasury yields were 16% and mortgages were 18%) generated a spike, but velocity soon returned to its uptrending channel. The speculative excesses of the dot-com era pushed velocity to unprecedented heights.

Given the extremes in velocity, it is unsurprising that it quickly fell in the dot-com bust. The Federal Reserve launched an unprecedented expansion of money, credit and liquidity that again pushed velocity up in the speculative frenzy of the housing bubble. But note that despite the vast expansion of money supply, the peak in the velocity of money was considerably lower than the dot-com peak.

OK, that’s the core of why I started thinking I was sure it just ain’t so. What Charles asserts here is that an expansion of the money supply lifts the velocity of money. In other words, that the velocity of both the pre-existing supply AND the additional supply increases as more supply is added. Even BECAUSE it is added. The more money, the faster it moves. The bigger you get, the faster you run.

And I don’t see that. To me, it’s counterintuitive. This implied correlation does not exist. The velocity of money doesn’t rise when you pump more of it into an economy, it rises because people feel more confident about spending it. For whatever reason that may be.

What’s happening today, and what Charles neglects to mention, is that huge amounts of Americans simply no longer have money to spend. And no matter how much extra is pumped in through QE, it fails to reach them. Moreover, they’re all maxed out on debt. So even if they would get some extra, it would go towards debt repayment. And it does.

That’s what the money velocity graph tells us. Velocity began to tank around 1997, and apart from the housing bubble borrowing boom, has kept tanking until now. Beware of the differences between the graphs: the first one, money supply, runs from 1986 to 2015, while the second one, velocity, covers 1960 to 2015. So you can focus on the second part of graph no.2 to get them to line up.

And the first growth spurt in the velocity graph doesn’t correspond with a similar spurt in supply. In fact, the correlation looks pretty much inverse: the more supply, the less velocity. Apart from the housing casino boom blip perhaps. Which Charles attempts to address next:

Since the collapse of that speculative bubble, the Fed’s all-in expansion of money, credit and liquidity has failed to stem the absolutely unprecedented collapse of money velocity. Clearly, expanding money, credit and liquidity no longer generates any velocity.

That’s because it never has. Expanding money, credit and liquidity has never generated any velocity. It’s always been only about confidence – and private debt levels.

Rather, the inescapable conclusion is that Fed policies have effectively crashed the velocity of money.

No, that conclusion is not just not inescapable, it’s flat out wrong. Unless perhaps you would mean that the policies have greatly impoverished the consumer, but that’s not what Charles is saying. He doesn’t mention consumers. His point seems to be that in earlier days, increases in supply did indeed lead to increases in velocity, ostensibly in the financial world.

To the extent that policies, Fed or otherwise, have tempted Americans to enter the ‘investment casino’, one might claim that down the road, such policies have crashed velocity. But the money supply was not rising all that much when the dot.com bubble was happening, and when the real big supply kahuna came, velocity crashed.

Not because of Fed policies, but because of debt, and of people being maxed out. And one could, if one were inclined to do so, blame that as much on the repeal of Glass-Steagall as on the Fed.

How is this possible? Longtime correspondent Eric A. proposed an insightful explanation. Here is Eric’s commentary:

“You know how you say that the economy is locked up in fiefdoms, and they’re picking winners and losers, as part of colluding the prices? Well this adjustment of prices locks out certain people, like say, the young from housing. So houses don’t sell, they stagnate. But what are we really looking at? Velocity.

Velocity is an indicator that buyers and sellers agree on a price, that the price is “right” and not an outlier. That’s why you see a stock move on high volume “confirming” the move, because it means the price wasn’t “right” at the previous level, while more people agree the new price is fair.

If prices are allowed to go where they need to without pressure and manipulation, you will always have velocity, as the most buyers and sellers will always agree at some price. Because this is true, low velocity cannot happen in a free market.

That is half right, but only half. because it suggests that there’s always a price at which people will buy. There isn’t if people have no money to buy with. That’s why the housing market crashed the way it did, and would be much worse to this day without ZIRP tempting people once more into foolish purchases (foolish because ZIRP distorts markets, but can’t do that forever).

Which means the only reason for low velocity (in this or the previous Depressions) is that someone has somehow managed to get an edge that prevents them from selling, from liquidating, at the true price, i.e. the one the buyers will agree to.

This has another corollary, that the measure of velocity on the Fed’s own chart is the measure of the level of unnatural price manipulation on the market. We can watch this aggregate indicator of their failure in real time, by the Fed’s own hand, and we can know the manipulation is ending when it rises.

Sort of right, but… You can’t even begin to understand the velocity of money without including what consumers have to spend. That’s essentially what the velocity of money measures. What they have to spend plus how confident they are of having it to spend (again) tomorrow.

And you can throw in price manipulation, but that’s not the core, though it can’t be said to have zero influence. What’s certain is that the connection to Fed policies is very weak, if not tenuous. The Fed didn’t blow the housing bubble (money supply remained just about flat from 2005-2008), politics did.

So yes, the Fed, the governments, the insiders can manipulate to their heart’s content, as they’ve been doing, but that unnatural pressure goes somewhere. And the pressure diverts into velocity. As we saw in the Great Depression, or the Roman Empire, velocity can stagnate for 10, 20, or 1,000 years until the manipulation ends, property rights are restored, and we have a free market. History has shown that may be a bargain they’re willing to make, but it won’t do the rest of us a lot of good.”

Sounds about right, but ignores the role of millions of Americans with nothing left to spend. To repeat: 94+ million Americans not in the labor force, the quality of jobs diminishing so fast and so profoundly that the middle class is all but disappearing, and 40+ million US citizens on foodstamps.

There’s what’s the velocity of money graph reflects. And that part of that is due to manipulation, sure. But without including debt, the whole argument rings kind of hollow.

Thank you, Eric, for an explanation that intuitively rings true. Manipulating the PR optics (i.e. perception management) as a substitute for an open market doesn’t make you omnipotent, it makes you a hubris-soaked fool.

No argument on the last sentence, but that is not the core of what ‘just ain’t so’ here. You essentially can’t tell anything from the US velocity of money without looking at the American people.

Velocity of money does not rise because -or when- the money supply does, it rises when consumer spending does. And that happens when people feel confident. No additional supply is needed for that, just for money to move faster. And money doesn’t move faster just because -or when- there’s more of it.

Home › Forums › The Velocity of the American Consumer