Theodor Horydczak Lincoln Memorial 1925

There has been quite a bit of talk lately over the need for a new Plaza Accord, something several parties saw happening during this weekend’s G20 summit in Shanghai -hence the term ‘Shanghai Accord’-. (On September 22, 1985 at the Plaza Hotel in New York City, France, West Germany, Japan, the US, and the UK signed an accord to depreciate the US dollar vs the Japanese yen and German Deutschmark by intervening in currency markets).

Unless all the G20 finance ministers and central bankers gathered in China are in close and secretive cahoots, though, it doesn’t look like it is going to happen. And that seems to both make sense and not. What those advocating such an accord are calling for is a -large- devaluation of the Chinese yuan (RMB) vs the USD and yen -perhaps even the euro-, but the climate simply doesn’t look ripe for it.

Still, the problem is, if they don’t do it, they open the doors to a whole lot more volatility, unpredictability and losses in the markets. All things that those markets do not want. Because, like it or not, the yuan is overvalued, China’s fabricated trade numbers are increasingly under scrutiny, and a large devaluation could settle things at least for a while.

However, Beijing looks too full of hubris and pride -and inclusion in the IMF basket of currencies is an issue too- to do what seems natural. Lest we forget, no matter how much China seeks to obfuscate the numbers, everybody already knows that numbers like producer prices and exports, and most importantly imports, have seen steep falls, and for a long time too.

China’s oil tanks look as close to overflowing as the American ones, and without those oil imports, who knows who bad import numbers would have looked? So from a Chinese point of view, a cheaper yuan would mean much cheaper Chinese exports for global buyers, whereas the negative effect of more expensive imports would be relatively small.

But there’s the other side of the equation as well: other nations’ exports would see a potentially enormous effect of cheaper Chinese imports on their domestic manufacturing base. For countries like Germany, the US and Japan, any such devaluation may therefore be an absolute non-starter at this point.

That, however, leaves the fact that there is that large imbalance in currency (FX) markets, and that those markets, along with hedge funders like Kyle Bass, have already made it known that they will seek to exploit that imbalance to go after the yuan for profit. That finance ministers seem unable to ‘soften’ the imbalance will only make them more determined. It’s like the central bankers and finance ministers make their case for them.

A few news snippets from the past week. First, Tyler Durden’s take on BofA’s Michael Hartnett a week ago, who’s quite clear on why there should be a devaluation.

BofA: ‘Shanghai Accord’, Massive Central Bank Intervention Imminent

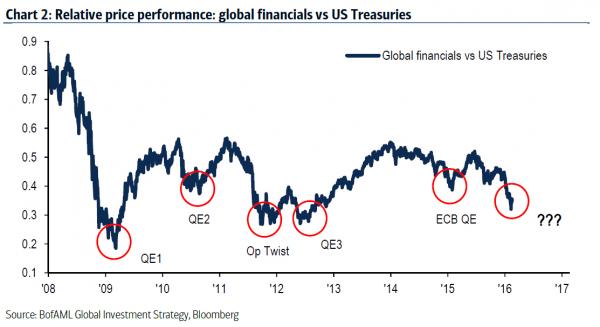

Any time the relative performance of global financials to US Treasuries has stumbled as far as it has, as shown in the chart below, it has meant one thing – a major central bank intervention was imminent. At least that’s the interpretation of BofA’s Michael Hartnett, who shows that in order to provide the kick for the bounce in this all too important “deflationary leading indicator”, central banks engaged in major unorthodox easing episodes, whether QE1-3, or the ECB’s QE.

Why intervene now? Here are the problems according to Hartnett:

• Problem 1: US economy in “bad Goldilocks”, i.e. US economy not hot/strong enough to lift global GDP & EPS; but not cold/bad enough to induce global coordinated response

• Problem 2: global policy-maker rhetoric in recent days shows “coordinated innocence” not stimulus, all blaming global economy for weak domestic economies (“Overseas factors are to blame”…Japan PM Abe; “drag on U.S. economy from greater-than-expected-slowdown in China & other EM economies“…FOMC minutes; “increasing concerns about the prospects for the global economy”…ECB Draghi; “the change in China’s growth rate can be attributed in part to weak performance of the global economy”…PBoC)Problem 2 is static, meant for media propaganda and jawboning; it can easily be removed once the global economy takes the next leg lower. Which incidentally would also resolve the gating factor of Problem 1 – as we have said for months, the Fed and its central bank peers need the political cover to launch more stimulus.

And in a reflexive world, where the “economy is the market”, this means just one thing – a big leg lower in stocks is the necessary and sufficient condition to once again push stocks higher, as policy failure is internalized, and global risk reprises from square 1. This is Bank of America’s summary, warning that unless a major policy intervention is enacted, the market will then sell off to the next support level, below the 1,812 which has proven so stable since August. Stabilization of “4C’s” (China, Commodities, Credit, Consumer) allowed SPX 1800 to hold/bounce to 1950-2000; weak policy stimulus in coming weeks could end rally/risk fresh declines to induce growth-boosting policy accord.

Next up, Bloomberg:

Barclays Says Sharp Yuan Devaluation Needed

A sharp, one-off devaluation of the yuan is among options China’s central bank might consider to stem capital outflows and shift market psychology to appreciation from depreciation, according to Barclays. The risk of such a move, which Barclays says would need to be in the region of 25% to alter perceptions, is rising as China’s foreign-exchange reserves plunge, analysts Ajay Rajadhyaksha and Jian Chang wrote in a report. Based on the current pace of decline in those holdings, there’s a six- to 12-month window before they drop to uncomfortable levels and measures such as capital controls or monetary tightening may also have to be looked at to curb the exodus of money, they said. All those options carry elements of danger.

Another rapid yuan depreciation could spook investors just as concern about the state of the global economy is growing and other central banks would likely follow, countering the beneficial impact on Chinese exports, the analysts said. Strict capital controls won’t work in an export-driven economy, while a move to policy tightening could slow growth and cause credit defaults, they said. “A devaluation of this magnitude seems impossible to ‘sell’ to the rest of the world,” according to the analysts at Barclays, the world’s third-biggest currency trader.

And then this from the FT, which confirms the huge question mark over the option:

Scepticism Rife Over G20 Move To Calm FX

Scepticism is rife that the G20 gathering of finance ministers will agree to co-ordinate currency policy but there is some belief it could provide a short-term boost to risk appetite. Japan has led calls for the two-day meeting in Shanghai to bring calmness to an unstable market with a broad-based FX strategy, seen by some market commentators as a reprise of the 1985 Plaza Accord that succeeded in weakening a rampant dollar. But those hopes have been knocked back by China and the US, and market expectations have been subdued in the run-up to the G20 meeting that ends with a communique on Saturday. “A grand solution like the Plaza Accord feels far-fetched”, said Peter Rosenstrich at the online bank Swissquote.

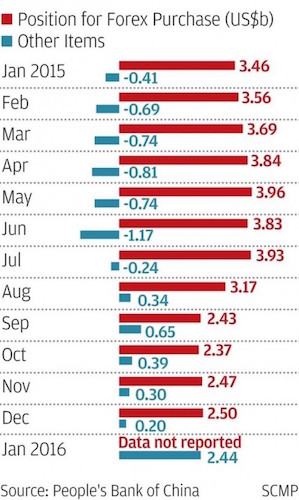

Then, the South China Morning Post a few days back on how Beijing apparently seeks to hide capital outflows data.

Sensitive Financial Data ‘Missing’ From PBOC Report On Capital Outflows

Sensitive data is missing from a regular Chinese central bank report amid concerns about capital outflow as the economy slows and the yuan weakens. Financial analysts say the sudden lack of clear information makes it hard for markets to assess the scale of capital flows out of China as well as the central bank s foreign exchange operations in the banking system. Figures on the “position for forex purchase” are regularly published in the People’s Bank of China’s monthly report on the “Sources and Uses of Credit Funds of Financial Institutions”. The December reading in foreign currencies was US$250 billion. But the data was missing in the central bank’s latest report. It seemed the information had been merged into the “other items” category, whose January figure was US$243.9 billion -a surge from US$20.4 billion the previous month.

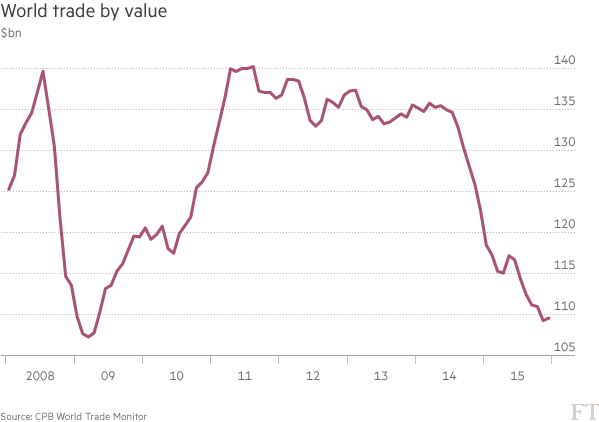

Combine that with new world trade numbers as reported by the FT, and you can’t help but wonder 1) what is going on with trade (though this is in USD, and that tweeks things somewhat), and 2) how much the yuan would have to drop to make up for the difference.

World Trade Falls 13.8% In Dollar Terms (FT)

Weaker demand from emerging markets made 2015 the worst year for world trade since the aftermath of the global financial crisis, highlighting rising fears about the health of the global economy. The value of goods that crossed international borders last year fell 13.8% in dollar terms — the first contraction since 2009 — according to the Netherlands Bureau of Economic Policy Analysis’s World Trade Monitor. Much of the slump was due to a slowdown in China and other emerging economies. The new data released on Thursday represent the first snapshot of global trade for 2015.

Next, Christopher Balding, an associate professor at Peking University HSBC Business School, who does them all one better by questioning even what may be the most widely accepted idea about the Chinese economy.

China Does Not Have a Trade Surplus

Whereas Chinese Customs reports $1.68 trillion and SAFE report $1.57 in goods imports into China, banks report paying $2.55 trillion for imports. In other words, funds paid for imported goods and services was $870-980 billion or 52-62% higher than official Customs and SAFE trade data. This level of discrepancy is extreme in both absolute and relative terms and cannot simply be called a rounding error but is nothing less than systemic fraud. If we adjust the official trade in goods and services balance to reflect cash flows rather than official headline trade data as reported by both Customs and SAFE, the differences are even worse.

According to official Customs and SAFE data, China ran a goods trade surplus of $593 or $576 billion but according to bank payment and receipt data, China ran a goods trade surplus of only $128 billion. If we include service trade, the picture worsens considerably. China via SAFE trade data reports a $207 billion trade deficit in services trade. Payment data reported via SAFE actually reports about $42 billion smaller deficit of $165 billion. In other words, the supposed trade surplus of $600 billion has become a trade in goods and services deficit of $36 billion. Expand to the current, through a significant primary income deficit, and the total current account deficit is now $124 billion.

That doesn’t leave much in one piece of what we’ve been told about the China growth miracle. No wonder the PBoC is ‘airbrushing’, as the NYT says. The problem with this is that analysts are already scrutinizing the data up -very- close, and they’re not going to be easily fooled anymore. For instance, in the case of the missing capital outflows data mentioned earlier, analysts say they can find them out through other channels anyway, and they will be that much more eager to do just that. Trying to bully them is senseless.

As China’s Economic Picture Turns Uglier, Beijing Applies Airbrush

This month, Chinese banking officials omitted currency data from closely watched economic reports. Weeks earlier, Chinese regulators fined a journalist $23,000 for reposting a message that said a big securities firm had told elite clients to sell stock. Before that, officials pressed two companies to stop releasing early results from a survey of Chinese factories that often moved markets. Chinese leaders are taking increasingly bold steps to stop rising pessimism about turbulent markets and the slowing of the country’s growth. As financial and economic troubles threaten to undermine confidence in the Communist Party, Beijing is tightening the flow of economic information and even criminalizing commentary that officials believe could hurt stocks or the currency.

The effort to control the economic narrative plays into a wide-reaching strategy by President Xi Jinping to solidify support at a time when doubts are swirling about his ability to manage the tumult. The persistence of that tumult was underscored on Thursday by a 6.4% drop in Chinese stocks, which are now down more than a fifth since the beginning of this year alone. The government moved to bolster confidence on Saturday by ousting its top securities regulator, who had been widely accused of contributing to the stock market turmoil. Mr. Xi is also putting pressure on the Chinese media to focus on positive news that reflects well on the party. But the tightly scripted story makes it ever more difficult to get information needed to gauge the extent of the country’s slowdown, analysts say. “Data disappears when it becomes negative,” said Anne Stevenson-Yang, co-founder of J Capital Research, which analyzes the Chinese economy.

A bit more of that through CNBC:

Chinese Accounting Is ‘Highly Questionable’

Financial reporting in China was back in the spotlight again Friday, with one strategist claiming Chinese businesses were using “accounting trickery” to mask underlying credit problems. China looks like it’s heading towards a credit bust, Chris Watling, CEO and chief market strategist at Longview Economics told CNBC on Friday, explaining that cash borrowed by mainland firms is primarily being used to service debts. “We’ve been looking a lot at Chinese accounting recently and it is highly questionable,” he said. The corporate sector is increasing borrowing to pay interest, while instances of fraud and default are on the rise, he added in a note published Thursday. He said there were many examples where operating profit has been high, while cash flow has been negative — a “classic sign” that firms aren’t generating a profit, he added.

Watling highlighted that the balance sheets of commercial banks were particularly worrying. “In an economy which has undergone a credit boom, all of the lending is not necessarily readily apparent from the top level data,” he said. “Accounting trickery is often at work..”

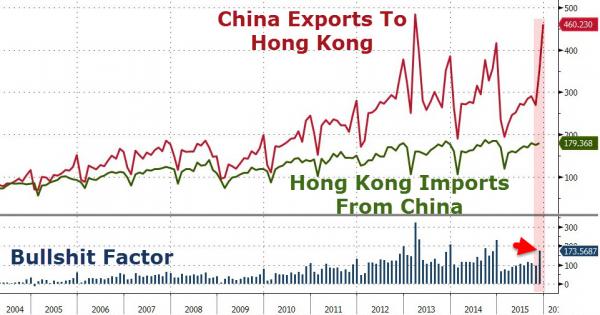

A good example of where the data fit with reality is this graph from ZH, which has a strong correlation with Balding’s claim that there is no Chinese trade surplus. What there is, is a lot of fake invoices.

And that inevitably leads to this kind of Bloomberg piece. Beijing is dying to get investments flowing in from abroad, but investors have no idea what potential profits will be worth in yuan, or, given capital controls, whether or when they can take them out of the country.

Yuan Uncertainty Scares Funds Away From China Bond Market

Yield versus yuan. That’s the crux of the investment decision now facing the global funds given more access to China’s bond market. While it offers the highest yields among the world’s major economies, PIMCO and Schroder Investment say exchange-rate risk is damping global demand for Chinese assets. Barclays said this week there’s a growing chance China will announce a sharp, one-time devaluation to change sentiment toward the currency and suggested such a move would need to be in the region of 25% to be effective. “Uncertainty around currency policy remains one of the larger hurdles for foreign investors,” said Rajeev De Mello at Schroder Investment in Singapore. “This should be resolved as the year progresses and would then be a signal to increase investments in Chinese government bonds.”

Of course the Chinese claim that this particular uncertainty is just a temporary thing, and it will all be fine soon, but that doesn’t look to be true. Or at least, it will remain an issue, and probably THE issue, as long as the yuan is seen as substantially overvalued. The PBoC and politburo thus far have apparently thought they could solve this by hiding data, uttering soothing words and/or bullying, but that’s not going to work. They need to devalue, and not by a few percent either.

Barclays says a devaluation “would need to be in the region of 25% to alter perceptions”, while Kyle Bass earlier mentioned a 30% to 50% move. Central bankers and politicians can try and stand still in the Mexican standoff until they’re blue in the face, but the markets will not stand still, and only get more nervous as time passes.

It doesn’t need to be done in Shanghai over the weekend, though one may wonder what will happen in the Chinese equity markets next week if nothing is done while there are great expectations now. From whatever angle we look at the issue, the outcome seems crystal clear: better get it done soon.

The US and Germany may not like it initially, but the uncertainty will hit them too, because the anticipation of a -strong- yuan devaluation affects their export markets, bonds, equities and currencies as well.

One problem we should not overlook may be that in the 1985 Plaza Accord, the strongest party -the US- wanted to get something done and got their devaluation wish. This time around, it’s not the strongest party that needs a devaluation, and the party that does need it doesn’t want it.

It is a very different set-up.

Home › Forums › The FX Mexican Standoff