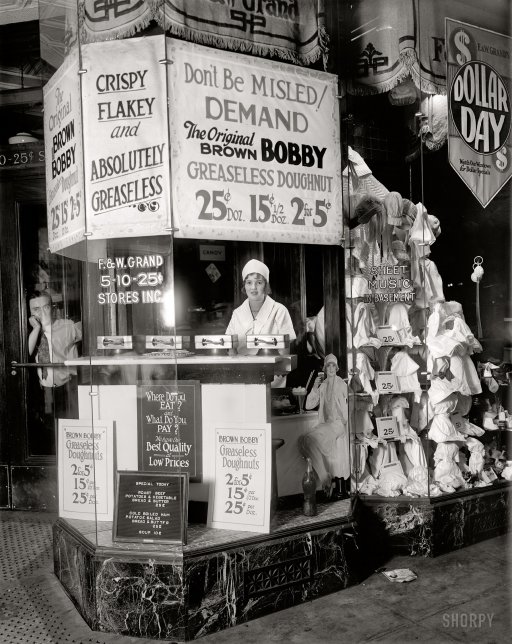

Harris&Ewing F.W. Grand store, Washington, DC 1925

Mario Draghi made another huge faux pas Thursday, but it looks like the entire world press has become immune to them, because it happens all the time, because they don’t realize what it means, and because they have a message if not a mission to sell. But still, none of these things makes it alright. Nor does Draghi’s denying it was a faux pas to begin with.

And while that’s very worrisome, ‘the public’ appear to be as numbed and dumbed down to this as the media themselves are -largely due to ’cause and effect’, no doubt-. We saw an account of a North Korean defector yesterday lamenting that her country doesn’t have a functioning press, and we thought: get in line.

It’s one thing for the Bank of England to research the effects of a Brexit. It’s even inevitable that a central bank should do this, but both the process and the outcome would always have to remain under wraps. Why it was ‘accidentally’ emailed to the Guardian is hard to gauge, but it’s not a big news event that such a study takes place. The contents may yet turn out to be, but that doesn’t look all that likely.

The reason the study should remain secret is, of course, that a Brexit is a political decision, and a country’s central bank can not be party to such decisions.

It’s therefore quite another thing for ECB head Mario Draghi to speak in public about reforms inside the eurozone. Draghi can perhaps vent his opinion behind closed doors, for instance in talks with politicians in European nations, but any and all eurozone reforms remain exclusively political decisions, even if they are economic reforms, and therefore Draghi must stay away from the topic, certainly in public. Far away.

There has to be a very clear line between central banks and governments. The latter should never be able to influence the former, because it would risk making economic policy serve only short term interests (until the next election). Likewise the former should stay out of the latter’s decisions, because that would tend to make political processes skewed disproportionally towards finance and the economy, at the potential cost of other interests in a society.

This may sound idealistic and out of sync with the present day reality, but if it does, that does not bode well. It’s dangerous to play fast and loose with the founding principles of individual countries, and perhaps even more with those of unions of sovereign nations.

Obviously, in the same vein it’s fully out of line for German FinMin Schäuble to express his opinion on whether or not Greece should hold a referendum on euro membership, or any referendum for that matter. Ye olde Wolfgang is tasked with Germany’s financial politics, not Greece’s, and being a minister for one of 28 EU members doesn’t give him the liberty to express such opinions. Because all EU nations are sovereign nations, and no foreign politicians have any say in other nations’ domestic politics.

It really is that simple, no matter how much of this brinkmanship has already passed under the bridge. Even Angela Merkel, though she’s Germany’s political leader, must refrain from comments on internal Greek political affairs. She must also, if members of her cabinet make comments like Schäuble’s, tell them to never do that again, or else. It’s simply the way the EU was constructed. There is no grey area there.

The way the eurozone is treating Greece has already shown that it’s highly improbable the union can and will last forever. Too many -sovereign- boundaries have been crossed. Draghi’s and Schäuble’s comments will speed up the process of disintegration. They will achieve the exact opposite of what they try to accomplish. The European Union will show itself to be a union of fairweather friends. In Greece, this is already being revealed.

The eurozone, or European monetary union, has now had as many years of economic turmoil as it’s had years of prosperity. And it’ll be all downhill from here on in, precisely because certain people think they can afford to meddle in the affairs of sovereign nations. The euro was launched on January 2002, and was in trouble as soon as the US was, even if this was not acknowledged right away. Since 2008, Europe has swung from crisis to crisis, and there’s no end in sight.

At the central bankers’ undoubtedly ultra luxurious love fest in Sintra, Portugal, where all protagonists largely agree with one another, Draghi on Friday held a speech. And right from the start, he started pushing reforms, and showing why he really shouldn’t. Because what he suggests is not politically -or economically- neutral, it’s driven by ideology.

He can’t claim that it’s all just economics. When you talk about opening markets, facilitating reallocation etc., you’re expressing a political opinion about how a society can and should be structured, not merely an economy.

Structural Reforms, Inflation And Monetary Policy (Mario Draghi)

Our strong focus on structural reforms is not because they have been ignored in recent years. On the contrary, a great deal has been achieved and we have praised progress where it has taken place, including here in Portugal. Rather, if we talk often about structural reforms it is because we know that our ability to bring about a lasting return of stability and prosperity does not rely only on cyclical policies – including monetary policy – but also on structural policies. The two are heavily interdependent.

So what I would like to do today in opening our annual discussions in Sintra is, first, to explain what we mean by structural reforms and why the central bank has a pressing and legitimate interest in their implementation. And second, to underline why being in the early phases of a cyclical recovery is not a reason to postpone structural reforms; it is in fact an opportunity to accelerate them.

Structural reforms are, in my view, best defined as policies that permanently and positively alter the supply-side of the economy. This means that they have two key effects. First, they lift the path of potential output, either by raising the inputs to production – the supply and quality of labour and the amount of capital per worker – or by ensuring that those inputs are used more efficiently, i.e. by raising total factor productivity (TFP).

And second, they make economies more resilient to economic shocks by facilitating price and wage flexibility and the swift reallocation of resources within and across sectors. These two effects are complementary. An economy that rebounds faster after a shock is an economy that grows more over time, as it suffers from lower hysteresis effects. And the same structural reforms will often increase both short-term flexibility and long-term growth.

And earlier in the -long- speech he said: “Our strong focus on structural reforms is not because they have been ignored in recent years. On the contrary, a great deal has been achieved and we have praised progress where it has taken place, including here in Portugal.

So Draghi states that reforms have already been successful. Wherever things seem to go right, he will claim that’s due to ‘his’ reforms. Wherever they don’t, that’s due to not enough reforms. His is a goalseeked view of the world.

He claims that the structural reforms he advocates will lead to more resilience and growth. But since these reforms are for the most part a simple rehash of longer running centralization efforts, we need only look at the latter’s effects on society to gauge the potential consequences of what Draghi suggests. And what we then find is that the entire package has led to growth almost exclusively for large corporations and financial institutions. And even that growth is now elusive.

Neither reforms nor stimulus have done much, if anything, to alleviate the misery in Greece or Spain or Italy, and Portugal is not doing much better, as the rise of the Socialist Party makes clear. The reforms that Draghi touts for Lisbon consist mainly of cuts to wages and pensions. How that is progress, or how it has made the Portuguese economy ‘more resilient’, is anybody’s guess.

Resilience cannot mean that a system makes it easier to force you to leave your home to find work, but that is exactly what Draghi advocates. Instead, resilience must mean that it is easier for you to find properly rewarded work right where you are, preferably producing your own society’s basic necessities. That is what would make your society more capable of withstanding economic shocks.

Still, it’s the direct opposite of what Draghi has in mind. Draghi states that [structural reforms] “.. make economies more resilient to economic shocks by facilitating price and wage flexibility and the swift reallocation of resources within and across sectors.”

That obviously and simply means that, if it pleases the economic elites who own a society’s assets, your wages can more easily be lowered, prices for basic necessities can be raised, and you yourself can be ‘swiftly reallocated’ far from where you live, and into industries you may not want to work in that don’t do anything to lift your society.

Whether such kinds of changes to your society’s framework are desirable is manifestly a political theme, and an ideological one. They may make it easier for corporations to raise their bottom line, but they come at a substantial cost for everyone else.

Draghi tries to push a neoliberal agenda even further, and that’s a decidedly political agenda, not an economic one.

There was a panel discussion on Saturday in which Draghi defended his forays into politics, and he was called on them:

Draghi and Fischer Reject Claim Central Banks Are Too Politicised

The ECB president on Saturday said his calls were appropriate in a monetary union where growth prospects had been badly damaged by governments’ resistance to economic reforms. Mr Draghi said it was the central bank’s responsibility to comment if governments’ inaction on structural reforms was creating divergence in growth and unemployment within the eurozone, which undermined the existence of the currency area. “In a monetary union you can’t afford to have large and increasing structural divergences,” the ECB president said. “They tend to become explosive.”

He even claims it’s his responsibility to make political remarks….

Mr Draghi’s defence of the central bank came after Paul De Grauwe, an academic at the London School of Economics, challenged his calls for structural reforms earlier in the week. Mr De Grauwe said central banks’ push for governments to take steps that removed people’s job protection would expose monetary policy makers to criticism over their independence to set interest rates.

The ECB president [..] said central banks had been wrong to keep quiet on the deregulation of the financial sector. “We all wish central bankers had spoken out more when regulation was dismantled before the crisis,” Mr Draghi said. A lack of structural reform was having much more of an impact on poor European growth than in the US, he added.

De Grauwe is half right in his criticism, but only half. It’s not just about the independence to set interest rates, it’s about independence, period. A central bank cannot promote a political ideology disguised as economic measures. It’s bad enough if political parties do this, or corporations, but for central banks it’s an absolute no-go area.

Pressure towards a closer economic and monetary union in Europe is doomed to fail because it cannot be done without a closer political union at the same time. They’re all the same thing. They’re all about giving up sovereignty, about giving away the power to decide about your own country, society, economy, your own life. And Greeks don’t want the same things as Germans, nor do Italians want to become Dutch.

Because of Greece, many EU nations are now increasingly waking up to what a ‘close monetary union’ would mean, namely that Germany would be increasingly calling the shots all over Europe. No matter how many technocrats Brussels manages to sneak into member countries, there’s no way all of them would agree, and it would have to be a unanimous decision.

Draghi’s remarks therefore precipitate the disintegration of Europe, and it would be good if more people would recognize and acknowledge that. Europe are a bunch of fairweather friends, and if everyone is not very careful, they’re not going to part ways in a peaceful manner. The danger that this would lead to the exact opposite of what the EU was meant to achieve, is clear and present.