Salvador Dalí Mi esposa desnuda 1945

“Once the Fed stops buying that paper, the dealers will have a lot less cash and that means a lot more selling.”

• Why the Stock Market’s Up and Why it Won’t Last (MO)

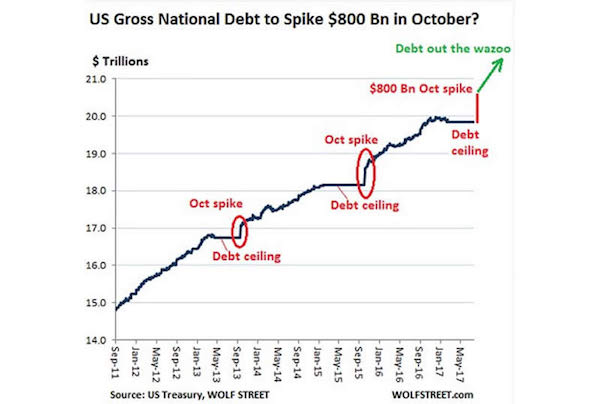

The U.S. Treasury has been up against its debt ceiling since March 15 when the ceiling was re-imposed. Since then, there has been no net new issuance from the Treasury. The Treasury has run down its cash balances and borrowed internally from its own resources, which are not subject to the ceiling. This period has been very helpful to the financial markets. With the federal government not selling any net new supply of securities—just rolling the maturing stuff over—the markets have been flush with cash that would otherwise have been absorbed by the government. This hit of extra liquidity is about to disappear and then some. President Trump has made a three-month debt ceiling deal with the Democrats which means that the Treasury can resume borrowing without restrictions through December.

This increase in the debt ceiling is needed to reliquify the federal government (which is down to $38 billion in cash) and repay the internal funds the Treasury raided since the debt ceiling was imposed back in March. The Treasury needs to borrow a substantial amount of money. There hasn’t been a material increase in the Treasury’s borrowing schedule yet, but it is coming. The Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC), a group of senior Wall Street executives, has advised the Treasury to issue $501 billion in net new supply in the fourth quarter, virtually all in November and December, and the Treasury almost always follows the TBAC script. That’s an outrageous amount of money. The cash the Treasury needs is not sitting somewhere in primary dealer bank accounts; it’s invested in the financial markets. Securities will have to be sold to accommodate this new issuance.

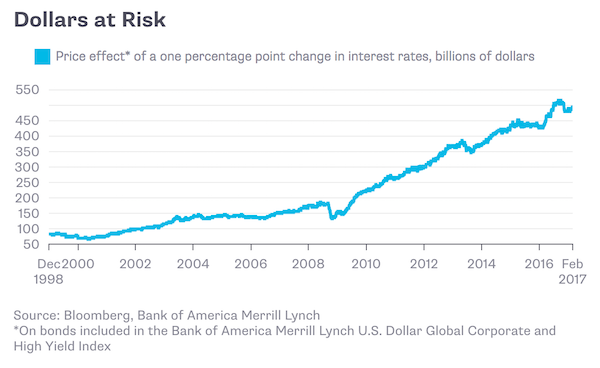

This is not new. A borrowing spike happens every time we have an increase in the debt ceiling as the chart demonstrates. Note that this chart reflects an estimate of net new issuance needed to return to last year’s cash on hand and was produced before TBAC had issued its recommendations. TBAC is proposing to move more slowly. Nonetheless, past funding spikes are clearly demarcated and the next one is going to be big. While Treasury supply will increase, the trend of demand for Treasuries has been going the other way. Bid coverage at auctions has been declining in recent months and the largest banks have been reducing their inventories of Treasury securities. Falling demand in the face of increasing supply is a recipe for a bear market in bonds. Bond yields will rise and that will put pressure on stocks as well.

The Federal Reserve has given the market extraordinary support over the past eight years by financing most new Treasury supply. Even after it stopped outright QE in November of 2014, the Fed continued to buy $25–$45 billion per month in maturing Mortgage Backed Securities from the primary dealers. That cashed up the dealers and helped finance their purchases of new Treasuries. But now, the Fed intends to join the Treasury as a net seller of Treasuries (and MBS) as it starts to reduce its balance sheet this fall. Once the Fed stops buying that paper, the dealers will have a lot less cash and that means a lot more selling.

“These companies have a record amount of cash and they’re more deeply indebted than ever before.”

• The Great Corporate Cash Shell Game (BBG)

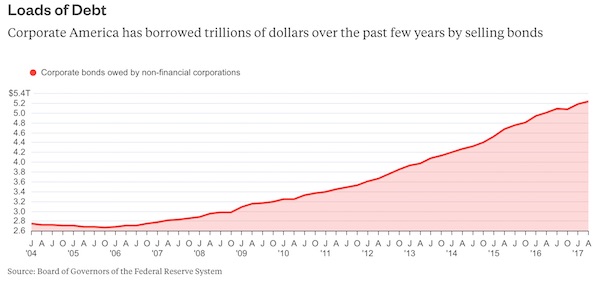

There’s a mystery hidden on the balance sheets of Corporate America: These companies have a record amount of cash and they’re more deeply indebted than ever before.This seems paradoxical and kind of silly. Why raise money from bond investors when you already have the liquid assets on hand? As Bloomberg News reported Thursday, non-financial companies’ liquid assets, which include foreign deposits, currency as well as money-market and mutual fund shares, reached a record of almost $2.3 trillion in the second quarter. That’s an increase of nearly 60% since mid-2009. This cash cushion also appears sort of comforting; companies can do whatever they want. They’re rich. But in reality, it is neither silly nor overly comforting.

First of all, a disproportionate amount of the cash is held by the biggest companies, such as Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet and General Electric, and it is mostly held in overseas accounts. These corporations can’t bring that cash back without incurring steep tax bills, so they’ve been keeping it offshore. When they need money, they simply raise dollars by borrowing from the bond market at record-low rates. Indeed, the amount of bonds issued by these companies has surged, rising 66% from mid-2009 to $5.24 trillion of bonds outstanding as of the end of June, Federal Reserve data show. That isn’t necessarily a recipe for default because a large chunk of this is an exercise in financial engineering aimed at avoiding onerous taxes. But it has consequences.

First, it limits the benefit to the economy if and when those tax policies are changed because much of the money has already been released through the bond market. And second, to the extent that companies have cash, they’re not using enough of it for exciting projects. There hasn’t been a tremendous wave of innovation or salary increases. Instead, companies have repurchased billions of dollars of their own shares, which is great for the stock market but doesn’t do a whole lot to bolster economic growth.

A bit poorly written, but still: “For each $1.00 the economy grew in this 1 year period the total debt outstanding increased by $5.48.”

• Debt Has Become A Way Of Life In Canada (OweC)

The borrowing and spending binge by Canadian households, businesses and governments (all levels) continues unabated. Growing the debt in the economy significantly faster than the economy itself grows seems to have developed into a way of life in Canada. At the end of June, 2017 the total debt outstanding in Canada was $7.51 trillion. At the end of June, 2016 it was $7.13 trillion. In the 1 year period from the end of June, 2016 to the end of June, 2017 it increased by $375 billion. This is an increase of 5.2%. The approximate beginning of the global financial crisis was June, 2007. At the end of June, 2007 the total debt outstanding in Canada was $3.99 trillion. In the last 10 years it has increased by $3.52 trillion. This is an increase of 88.3%. At the end of June, 2017 the total debt outstanding of domestic non-financial sectors was $5.32 trillion.

At the end of June, 2016 the total debt outstanding of domestic non-financial sectors was $5.04 trillion. In the 1 year period from the end of June, 2016 to the end of June, 2017 it increased by $278 billion. This is an increase of 5.5%. At the end of June, 2007 the total debt outstanding of domestic non-financial sectors was $2.84 trillion. In the last 10 years it has increased by $2.47 trillion. This is an increase of 86.9%. At the end of June, 2017 the annual GDP at market prices in Canada was $2.12 trillion, and in the preceding 1 year it grew by 6.3%, – ie: the size of the economy grew by $133.9 billion. In the 1 year period from the end of June, 2016 to the end of June, 2017 the total debt outstanding in Canada increased by $375 billion. For each $1.00 the economy grew in this 1 year period (using the GDP at market prices metric) the total debt outstanding increased by $2.80.

Looking at just the total debt outstanding of domestic non-financial sectors in Canada: In the 1 year period from the end of June, 2016 to the end of June, 2017 the total debt outstanding of domestic non-financial sectors increased by $278 billion. For each $1.00 the economy grew in this 1 year period (using the gdp at market prices metric) the total debt outstanding of domestic non-financial sectors increased by $2.08. At the end of June, 2017 the total debt outstanding in Canada was 3.5 times greater than our annual gdp at market prices, and looking at just the total debt outstanding of domestic non-financial sectors, that was 2.5 times greater than our annual gdp at market prices. [..] In the 1 year period from the end of June, 2016 to the end of June, 2017 the total debt outstanding in Canada increased by $375 billion. For each $1.00 the economy grew in this 1 year period the total debt outstanding increased by $5.48.

Communities and societies don’t matter. Only money does.

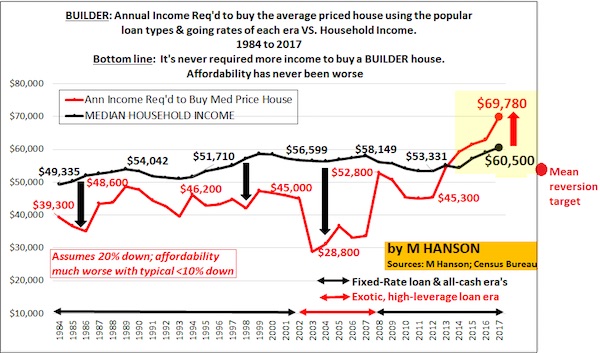

• Housing Affordability NEVER Worse…By a Long-Shot (Hanson)

My chart highlights how for DECADES the income required to buy a median priced house – using popular programs & rates for each era – remained mostly flat (red line) and WELL BELOW the level of household income (black line). How could house prices rise so much for decades but income required to buy (red) them remain flattish? Because of the accompanying falling rates/easing credit guideline cycle. In fact, during Bubble 1.0 house prices soared but exotic loans legitimately made them more affordable than ever, as shown.

But in ’12, as trillions in unorthodox capital, credit & liquidity began to drive massive speculation (just like Bubble 1.0) income required to buy began to surge, with prices, shooting above median HH income (boxed in yellow). Meaningful sales growth with this affordability backdrop is impossible. …This is the point in this inflationary cycle at which affordability detached from end-user fundamentals. Now, in ’17, end-user purchase power & house prices have never been more diverged from the multi-decade trend line and a mean reversion – via surging wages, new era exotic loans, plunging rates, and/or falling house prices, as speculation ebbs – is inevitable.

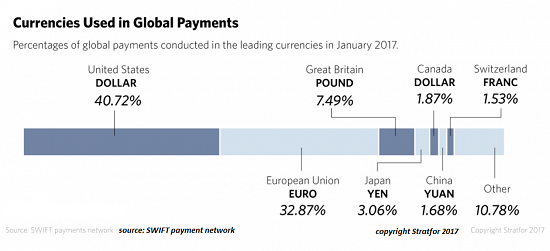

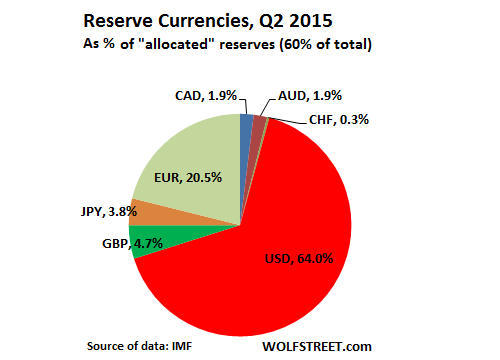

Must read. Like Charles, I don’t see it either. There is nothing to replace the USD for the foreseeable future.

• The Demise of the Dollar: Don’t Hold Your Breath (CH Smith)

Every form of credit/debt is denominated in a currency. A Japanese bond is denominated in yen, for example. The bond is purchased with yen, the interest is paid in yen, and the coupon paid at maturity is in yen. What gets tricky is debt denominated in some other currency. Let’s say I take out a loan denominated in quatloos. The current exchange rates between USD and quatloos is 1 to 1: parity. So far so good. I convert 100 USD to 100 quatloos every month to make the principal and interest payment of 100 quatloos. Then some sort of kerfuffle occurs in the FX markets, and suddenly it takes 2 USD to buy 1 quatloo. Oops: my loan payments just doubled. Where it once only cost 100 USD to service my loan denominated in quatloos, now it takes $200 to make my payment in quatloos. Ouch. Notice the difference between payments, reserves and debt: payments/flows are transitory, reserves and debt are not.

What happens in flows is transitory: supply and demand for currencies in this moment fluctuate, but flows are so enormous–trillions of units of currency every day–that flows don’t affect the value or any currency much. FX markets typically move in increments of 1/100 of a percentage point. So flows don’t matter much. De-dollarization of flows is pretty much a non-issue. What matters is demand for currencies that is enduring: reserves and debt.The same 100 quatloos can be used hundreds of times daily in payment flows; buyers and sellers only need the quatloos for a few seconds to complete the conversion and payment. But those needing quatloos for reserves or to pay long-term debts need quatloos to hold. The 100 quatloos held in reserve essentially disappear from the available supply of quatloos.

Another source of confusion is trade flows. If the U.S. buys more stuff from China than China buys from the U.S., goods flow from China to the U.S. and U.S. dollars flow to China. As China’s trade surplus continues, the USD just keep piling up. What to do with all these billions of USD? One option is to buy U.S. Treasury bonds (debt denominated in dollars), as that is a vast, liquid market with plenty of demand and supply. Another is to buy some other USD-denominated assets, such as apartment buildings in Seattle. This is the source of the petro-dollar trade. All the oil/gas that’s imported into the U.S. is matched by a flow of USD to the oil-exporting nations, who then have to do something with the steadily increasing pile of USD.

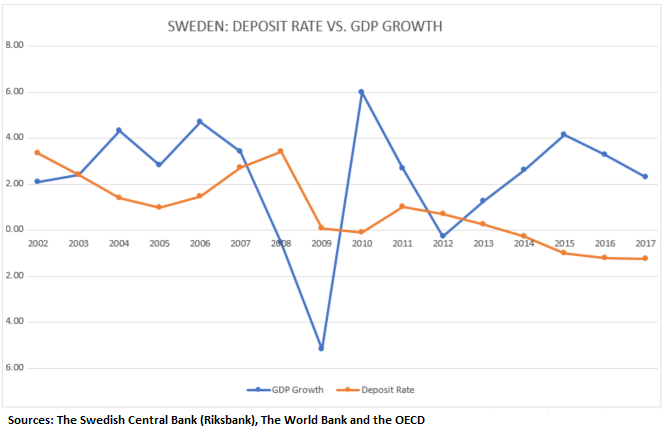

The USD is still the dominant reserve currency, despite decades of diversification. Global reserves (allocated and unallocated) are over $12 trillion. Note that China’s RMB doesn’t even show up in allocated reserves–it’s a non-player because it’s pegged to the USD. Why hold RMB when the peg can be changed at will? It’s lower risk to just hold USD. While total global debt denominated in USD is about $50 trillion, the majority of this is domestic, i.e. within the U.S. economy. $11 trillion has been issued to non-banks outside the U.S., including developed and emerging market debt:

Well, not entirely.

• China Slashes Trade Ties With North Korea (BBC)

China has moved to limit North Korea’s oil supply and will stop buying textiles from the politically isolated nation, it said on Saturday. China is North Korea’s most important trading partner, and one of its only sources of hard currency. The ban on textiles trade will hurt Pyongyang’s income, while China’s oil exports are the country’s main source of petroleum products. The tougher stance follows North Korea’s latest nuclear test this month. The United Nations agreed fresh sanctions – including the textiles and petroleum restrictions – in response. A statement from China’s commerce ministry said restrictions on refined petroleum products would apply from 1 October, and on liquefied natural gas immediately.

A limited amount, allowed under the UN resolution, would still be exported to North Korea. The current volume of trade between the two countries – and how much the new limits reduce it by – is not yet clear. But the ban on textiles – Pyongyang’s second-biggest export – is expected to cost the country more than $700m a year. China and Russia had initially opposed a proposal from the United States to completely ban oil exports, but later agreed to the reduced measures. North Korea has little energy production of its own, but does refine some petroleum products from crude oil it imports – which is not included in the new ban. The AFP news agency reports that petrol prices in Pyongyang have risen by about 20% in the past two months.

Spring cleaning: “Russia’s central bank has reportedly now closed more than a third of the country’s banks – approximately 300 lenders – in the last three years..”

• Russia Steps In To Prevent ‘Domino Effect’ In Its Banking Sector (CNBC)

Russia’s central bank has been forced to rescue two major lenders in less than a month, intensifying concerns among global investors that a systemic banking crisis could be in the offing. The Russian government’s latest rescue of a major bank was confirmed on Thursday, when the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) said it had nationalized the country’s 12th largest lender in terms of assets, B&N Bank. Last month, the CBR stepped in to launch one of the largest bank rescues in Russia’s history when Otkritie Bank required a bailout to help plug a $7 billion hole in its balance sheet. Russia’s central bank moved to dismiss intensifying concerns that a brewing systemic crisis could be forthcoming on Thursday, as it said its second major bank nationalization in three weeks had prevented a “domino effect” in the country’s ailing banking sector.

“We realized that it’s better to isolate a bit more so that the domino effect does not arise, and according to the results of this work the domino effect is excluded, there is no risk of this,” Vasily Pozdyshev, deputy governor at the CBR, told a press conference as reported by state media. B&N Bank requires an estimated capitalization of around $4.3 billion to $6 billion, according to Pozdyshev, an amount approximately equivalent to 25% of the lender’s balance sheet. The failure of two major lenders in relatively quick succession has fueled anxiety over the health of Russia’s banking sector, which has been hampered by an economic slowdown and Western sanctions in recent years.

In 2014, Russian regulators were jolted into action after a dramatic slump in oil prices as well as tough international sanctions for its annexation of Crimea and Russia’s perceived role in destabilizing eastern Ukraine. The CBR has been attempting to clean up the banking sector since 2013, shutting down scores of banks that it believed represented a risk to the system. Russia’s central bank has reportedly now closed more than a third of the country’s banks – approximately 300 lenders – in the last three years as it sought to eradicate undercapitalized institutions.

Brexit becomes expensive.

• UK’s Credit Rating Downgraded By Moody’s (BBC)

The UK’s credit rating has been cut over concerns about the UK’s public finances and fears Brexit could damage the country’s economic growth. Moody’s, one of the major ratings agencies, downgraded the UK to an Aa2 rating from Aa1. It said leaving the European Union was creating economic uncertainty at a time when the UK’s debt reduction plans were already off course. Downing Street said the firm’s Brexit assessments were “outdated”. The other major agencies, Fitch and S&P, changed their ratings in 2016, with S&P cutting it two notches from AAA to AA, and Fitch lowering it from AA+ to AA.

Moody’s said the government had “yielded to pressure and raised spending in several areas” including health and social care. It says revenues were unlikely to compensate for the higher spending. The agency said because the government had not secured a majority in the snap election it “further obscures the future direction of economic policy”. It also said Brexit would dominate legislative priorities, so there could be limited capacity to address “substantial” challenges. It added “any free trade agreement will likely take years to negotiate, prolonging the current uncertainty for business”. Moody’s has also changed the UK’s long-term issuer and debt ratings to “stable” from “negative”.

Uber was allowed to grow massively, elbowing any competition out of the way. It’s just dumb.

• The Scandals That Brought Down Uber (Ind.)

Transport for London has announced it will not renew ride-sharing app Uber’s licence, because it had identified a “lack of corporate responsibility” in the company. The statement highlighted four major areas of concern: the company’s approach to reporting criminal offences, the obtaining of medical certificates, its compliance with Enhanced Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) checks on employees, and its use of controversial Greyball software to “block regulatory… access to the app”. The company has recently been dogged by a number of corporate scandals in the UK and its international operations, which ultimately led to the resignation of CEO Travis Kalanick in June. Uber has repeatedly come under fire for its handling of allegations of sexual assault by its drivers against passengers.

Freedom of Information data obtained by The Sun last year showed that the Metropolitan Police investigated 32 drivers for rape or sexual assault of a passenger between May 2015 and May 2016. In August, Metropolitan Police Inspector Neil Billany wrote to TfL about his concern that the company was failing to properly investigate allegations against its drivers. He revealed the company had continued to employ a driver after he was accused of sexual assault. According to Inspector Billany, the same driver went on to assault another female passenger before he was removed. The letter said: “By not reporting to police promptly, Uber are allowing situations to develop that clearly affect the safety and security of the public.”

The statement by London’s transport body also expresses concern about “its approach to explaining the use of Greyball in London”. In March it emerged that Uber had been secretly using a tool called Greyball to deceive law enforcement officials in a number of US cities where the company flouted state regulations. Greyball used personal data of individuals it believed were connected to local government and ensured that its drivers would not pick them up if they requested a ride on the app. It was used in Portland, Oregon, Philadelphia, Boston, and Las Vegas, as well as France, Australia, China, South Korea and Italy. Uber denies ever using the software in the UK.

Politicians are too scared to call for regulation of things they don’t understand.

• Uber Had This Coming – It Was Never Just A ‘Tech Platform’ (Ind.)

Uber isn’t the only sharing economy app that has become part of daily life in the capital. Since 2008, over four million people have stayed in an Airbnb in London. The company, which links guests up with empty rooms or homes in the capital, recently came under fire in the US for not properly screening a host who attempted to sexually assault a woman (a spokesman for Airbnb later told The Independent that a background check had been done on the host and that there had been no prior convictions). The legal ruling over Uber could now bring the responsibilities of other companies such as Airbnb into the limelight. The rapid proliferation of these types of “gig economy” companies over the past few years has meant that many of them have forgotten their basic responsibilities toward their customers.

As The Independent’s Josie Cox has written, they forgot that the sharing economy business model was based on trust – we had to have confidence that the strangers we were sharing cars with were safe, and they couldn’t provide that. For too long, Uber tried to evade its role as anything more than a provider of tech. But we were never just sharing software; we were sharing our lives. Uber tried to get away with pretending it was a neutral software platform for far too long – all it did was link people together, and its responsibilities went as far as fixing glitches. But it was always a private taxi hire firm. It was a company with employees, who it should have been paying properly from that start, and customers, who it should have been protecting.

“We’re only two days past the Hurricane Maria’s direct hit on Puerto Rico and there is no phone communication across the island, so we barely know what has happened. We’re weeks past Hurricanes Irma and Harvey, and news of the consequences from those two events has strangely fallen out of the news media. Where have the people gone who lost everything? The news blackout is as complete and strange as the darkness that has descended on Puerto Rico.”

• Puerto Rico Is Back In The 18th Century (Kunstler)

Ricardo Ramos, the director of the beleaguered, government-owned Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, told CNN Thursday that the island’s power infrastructure had been basically “destroyed” and will take months to come back “Basically destroyed.” That’s about as basic as it gets civilization-wise. Residents, Mr. Ramos said, would need to change the way they cook and cool off. For entertainment, old-school would be the best approach, he said. “It’s a good time for dads to buy a ball and a glove and change the way you entertain your children.” Meaning, I guess, no more playing Resident Evil 7: Biohazard on-screen because you’ll be living it — though one wonders where will the money come from to buy the ball and glove? Few Puerto Ricans will be going to work with the power off.

And the island’s public finances were in disarray sufficient to drive it into federal court last May to set in motion a legal receivership that amounted to bankruptcy in all but name. The commonwealth, a US territory, was in default for $74 billion in bonded debt, plus another $49 billion in unfunded pension obligations. So, Puerto Rico already faced a crisis pre-Hurricane Maria, with its dodgy electric grid and crumbling infrastructure: roads, bridges, water and sewage systems. Bankruptcy put it in a poor position to issue new bonds for public works which are generally paid for with public borrowing. Who, exactly, would buy the new bonds? I hear readers whispering, “the Federal Reserve.” Which is a pretty good clue to understanding the circle-jerk that American finance has become.

Some sort of bailout is unavoidable, though President Trump tweeted “No Bailout for Puerto Rico” after the May bankruptcy proceeding. Things have changed and the shelf-life of Trumpian tweets is famously brief. But the crisis may actually strain the ability of the federal government to pretend it can cover the cost of every calamity that strikes the nation — at least not without casting doubt on the soundness of the dollar. And not a few bonafide states are also whirling around the bankruptcy drain: Illinois, Connecticut, New Jersey, Kentucky. Constitutionally states are not permitted to declare bankruptcy, though counties and municipalities can. Congress would have to change the law to allow it. But states can default on their bonds and other obligations. Surely there would be some kind of fiscal and political hell to pay if they go that route.

Nobody really knows what might happen in a state as big and complex as Illinois, which has been paying its way for decades by borrowing from the future. Suddenly, the future is here and nobody has a plan for it. The case for the federal government is not so different. It, too, only manages to pay its bondholders via bookkeeping hocuspocus, and its colossal unfunded obligations for social security and Medicare make Illinois’ predicament look like a skipped car payment. In the meantime — and it looks like it’s going to be a long meantime – Puerto Rico is back in the 18th Century, minus the practical skills and simpler furnishings for living that way of life, and with a population many times beyond the carrying capacity of the island in that era.

Still 8 days to go. How can this remian peaceful? Will Rajoy try to provoke violence (if he isn’t already) and blame it on the Catalans?

• It Gets Ugly in Catalonia (DQ)

Madrid’s crackdown on Catalonia is already having one major consequence, presumably unintended: many Catalans who were until recently staunchly opposed to the idea of national independence are now reconsidering their options. A case in point: At last night’s demonstration, spread across multiple locations in Barcelona, were two friends of mine, one who is fanatically apolitical and the other who is a strong Catalan nationalist but who believes that independence would be a political and financial disaster for the region. It was their first ever political demonstration. If there is a vote on Oct-1, they will probably vote to secede. The middle ground they and hundreds of thousands of others once occupied was obliterated yesterday when a judge in Barcelona ordered Spain’s militarized police force, the Civil Guard, to round up over a dozen Catalan officials in dawn raids.

Many of them now face crushing daily fines of up to €12,000. The Civil Guard also staged raids on key administrative buildings in Barcelona. The sight of balaclava-clad officers of the Civil Guard, one of the most potent symbols of the not-yet forgotten Franco dictatorship, crossing the threshold of the seats of Catalonia’s (very limited) power and arresting local officials, was too much for the local population to bear. Within minutes almost all of the buildings were surrounded by crowds of flag-draped pro-independence protesters. The focal point of the day’s demonstrations was the Economic Council of Catalonia, whose second-in-command and technical coordinator of the referendum, Josep Maria Jové, was among those detained. He has now been charged with sedition and could face between 10-15 years in prison. Before that, he faces fines of €12,000 a day.

[..] yesterday’s police operation significantly — perhaps even irreversibly — weakens Catalonia’s plans to hold a referendum on October 1, as even the region’s vice-president Oriol Junqueras concedes. But that doesn’t mean Spain has won. As the editor of El Diario, Ignacio Escolar, presciently notes, yesterday’s raids may have been a resounding success for law enforcement, but they were an unmitigated political disaster that has merely intensified the divisions between Spain and Catalonia and between Catalans themselves. Each time Prime Minister Rajoy or one of his ministers speak of the importance of defending democracy while the Civil Guard seizes posters and banners related to the October 1 vote and judges rule public debates on the Catalan question illegal and then fine their participants, a fresh clutch of Catalan separatists is born.

In the days to come they will be swarming the streets, waving their flags, clutching their red carnations and singing their songs. For the moment, the mood is still one of hopeful, resolute indignation. But the mood of masses is prone to change quickly, and it’s not going to take much to ignite the anger.

Pilger was a Vietnam correspondent. He knows what he’s talking about.

• The Killing of History (John Pilger)

One of the most hyped “events” of American television, The Vietnam War, has started on the PBS network. The directors are Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. Acclaimed for his documentaries on the Civil War, the Great Depression and the history of jazz, Burns says of his Vietnam films, “They will inspire our country to begin to talk and think about the Vietnam war in an entirely new way”. In a society often bereft of historical memory and in thrall to the propaganda of its “exceptionalism”, Burns’ “entirely new” Vietnam war is presented as “epic, historic work”. Its lavish advertising campaign promotes its biggest backer, Bank of America, which in 1971 was burned down by students in Santa Barbara, California, as a symbol of the hated war in Vietnam. Burns says he is grateful to “the entire Bank of America family” which “has long supported our country’s veterans”.

Bank of America was a corporate prop to an invasion that killed perhaps as many as four million Vietnamese and ravaged and poisoned a once bountiful land. More than 58,000 American soldiers were killed, and around the same number are estimated to have taken their own lives. I watched the first episode in New York. It leaves you in no doubt of its intentions right from the start. The narrator says the war “was begun in good faith by decent people out of fateful misunderstandings, American overconfidence and Cold War misunderstandings”. The dishonesty of this statement is not surprising. The cynical fabrication of “false flags” that led to the invasion of Vietnam is a matter of record – the Gulf of Tonkin “incident” in 1964, which Burns promotes as true, was just one. The lies litter a multitude of official documents, notably the Pentagon Papers, which the great whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg released in 1971.

There was no good faith. The faith was rotten and cancerous. For me – as it must be for many Americans – it is difficult to watch the film’s jumble of “red peril” maps, unexplained interviewees, ineptly cut archive and maudlin American battlefield sequences. In the series’ press release in Britain – the BBC will show it – there is no mention of Vietnamese dead, only Americans. “We are all searching for some meaning in this terrible tragedy,” Novick is quoted as saying. How very post-modern. All this will be familiar to those who have observed how the American media and popular culture behemoth has revised and served up the great crime of the second half of the twentieth century: from The Green Berets and The Deer Hunter to Rambo and, in so doing, has legitimised subsequent wars of aggression. The revisionism never stops and the blood never dries. The invader is pitied and purged of guilt, while “searching for some meaning in this terrible tragedy”. Cue Bob Dylan: “Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son?”

I thought about the “decency” and “good faith” when recalling my own first experiences as a young reporter in Vietnam: watching hypnotically as the skin fell off Napalmed peasant children like old parchment, and the ladders of bombs that left trees petrified and festooned with human flesh. General William Westmoreland, the American commander, referred to people as “termites”. In the early 1970s, I went to Quang Ngai province, where in the village of My Lai, between 347 and 500 men, women and infants were murdered by American troops (Burns prefers “killings”). At the time, this was presented as an aberration: an “American tragedy” (Newsweek ). In this one province, it was estimated that 50,000 people had been slaughtered during the era of American “free fire zones”. Mass homicide. This was not news.