Robert Doisneau Vitrine, Galerie Romi, Paris 1948

“The bond market determines how much you pay to borrow money to buy a home, a car, or when you use your credit cards.”

• Will Trump Oversee The Financial Apocalypse? (Cohan)

Let’s face it: people’s eyes tend to glaze over when someone starts talking about bonds and interest rates. Which is why much of the audience inside the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, and those watching the livestream, probably missed the import of Gundlach’s answer. But the bond market is hugely important. The stock markets get most of the attention from the media, but the bond market, four times the size of the stock market, helps set the price of money. The bond market determines how much you pay to borrow money to buy a home, a car, or when you use your credit cards. The Bond King said the returns on bonds have been anemic at best for the past seven years or so.

While the Dow Jones Industrial Average has nearly quadrupled since March 2009, returns on bonds have averaged something like 2.5% for treasuries and something like 8.5% for riskier “junk” bonds. Gundlach urged investors to be “light” on bonds. Of course, that makes the irony especially rich for the Bond King. “I’m stuck in it,” he said of his massive bond portfolio. He said interest rates have bottomed out and been rising gradually for the past six years. (Rising interest rates hurt the value of the bonds you own, as bonds trade in inverse proportion to their yield. Snore . . .) Gundlach said his job now, on behalf of his clients, “is to get them to the other side of the valley.” When the bigger, seemingly inevitable hikes in interest rates come, “I’ll feel like I’ve done a service by getting people through,” he said. “That’s why I’m still at the game. I want to see how the movie ends.”

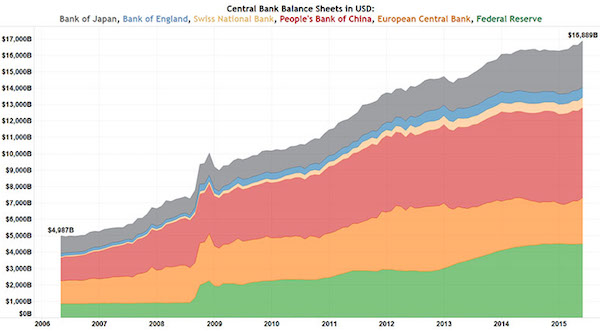

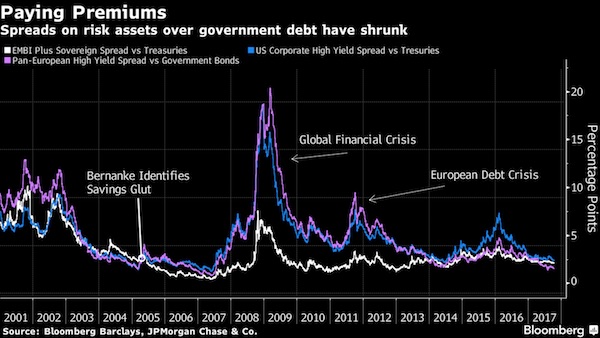

But it can’t end well. To illustrate his point about the risk in owning bonds these days, Gundlach shared a chart that showed how investors in European “junk” bonds are willing to accept the same no-default return as they are for U.S. Treasury bonds. In other words, the yield on European “junk” bonds is about the same—between 2% and 3%—as the yield on U.S. Treasuries, even though the risk profile of the two could not be more different. He correctly pointed out that this phenomenon has been caused by “manipulated behavior”—his code for the European Central Bank’s version of the so-called “quantitative easing” program that Ben Bernanke, the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, initiated in 2008 and that Mario Draghi, the head of the E.C.B., has taken to heart.

Bernanke’s idea was to have the Federal Reserve buy up trillions of dollars of bonds, increasing their price and lowering their yields. He figured lower interest rates would help jump-start an economy in recession. Whereas Janet Yellen, Bernanke’s successor, ended the Fed’s Q.E. program in 2014, Draghi’s version of it is still going, which has led to the “manipulation” that so concerns Gundlach. European interest rates “should be much higher than they are today,” he said, “. . . [and] once Draghi realizes this, the order of the financial system will be turned upside down and it won’t be a good thing. It will mean the liquidity that has been pumping up the markets will be drying up in 2018 . . . Things go down. We’ve been in an artificially inflated market for stocks and bonds largely around the world.”

Excellent from Schiff. The VIX/CAPE ratio looks to be a valuable tool.

• Calm Before The Storm (Peter Schiff)

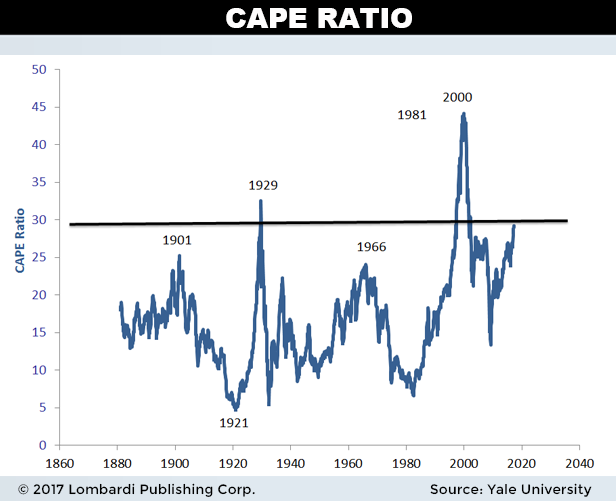

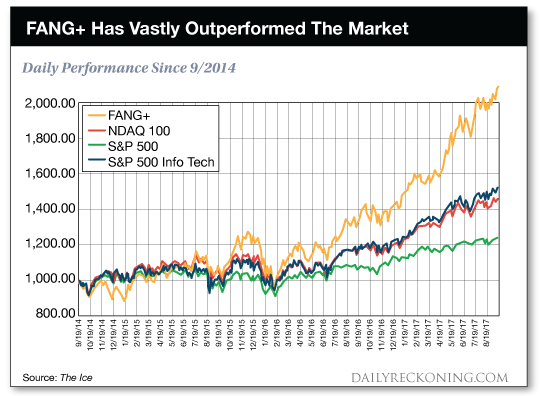

Before the crisis, there was still a strong belief that stock investing entailed real risk. The period of stock stagnation of the 1970s and 1980s was still well remembered, as were the crashes of 1987, 2000, and 2008. But the existence of the Greenspan/Bernanke/Yellen “Put” (the idea that the Fed would back stop market losses), came to ease many of the anxieties on Wall Street. Over the past few years, the Fed has consistently demonstrated that it is willing to use its new tool kit in extraordinary ways. While many economists had expected the Fed to roll back its QE purchases as soon as the immediate economic crisis had passed, the program steamed at full speed through 2015, long past the point where the economy had apparently recovered. Time and again, the Fed cited fragile financial conditions as the reason it persisted, even while unemployment dropped and the stock market soared.

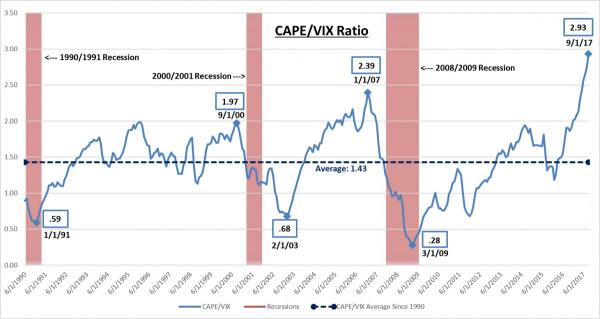

The Fed further showcased its maternal instinct in early 2016 when a surprise 8% drop in stocks in the first two weeks of January (the worst ever start of a calendar year on Wall Street) led it to abandon its carefully laid groundwork for multiple rate hikes in 2016. As investors seem to have interpreted this as the Fed leaving the safety net firmly in place, the VIX has dropped steadily from that time. In September of this year, the VIX fell below 10. Untethered optimism can be seen most clearly by looking at the relationship between the VIX and the CAPE ratio. Over the past 27 years, this figure has averaged 1.43. But just this month, the ratio approached 3 for the first time on record, increasing 100% in just a year and a half. This means that the gap between how expensive stocks have become and how little this increase concerns investors has never been wider. But history has shown that bad things can happen after periods in which fear takes a back seat.

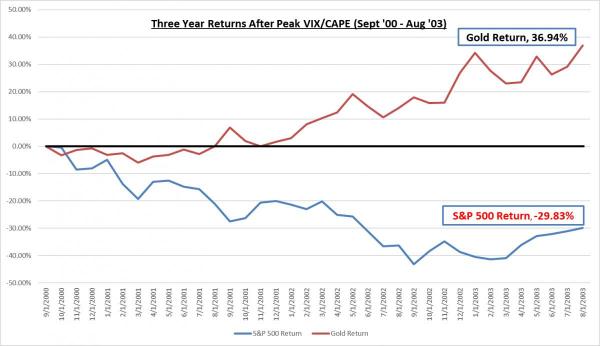

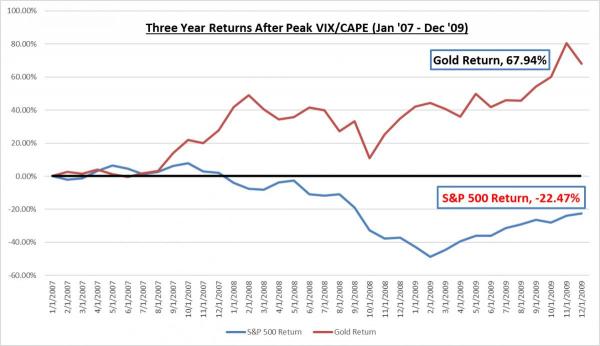

Investors may be trying to convince themselves that the outcome will be different this time around. But the only thing that is likely to be different is the Fed’s ability to limit the damage. In 2000-2002, the Fed was able to cut interest rates 500 basis points (from 6% to 1%) in order to counter the effects of the imploding tech stock bubble. Seven years later, it cut rates 500 basis points (from 5% to 0) in response to the deflating housing bubble. Stocks still fell anyway, but they probably would have fallen further if the Fed hadn’t been able to deliver these massive stimuli. In hindsight, investors would have been wise to move some funds out of U.S. stocks when the CAPE/VIX ratio moved into record territory. While stocks fell following those peaks, gold rose nicely.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. Created by Euro Pacific Capital from data culled from Bloomberg.

But interest rates are now at just 1.25%. If the stock market were again to drop in such a manner, the Fed has far less fire power to bring to bear. It could cut rates to zero and then re-launch another round of QE bond buying to flood the financial sector with liquidity. But that may not be nearly as effective as it was in 2008. Given that the big problem at that point was bad mortgage debt, the QE program’s purchase of mortgage bonds was a fairly effective solution (although we believe a misguided one). But propping up overvalued stocks, many of which have nothing to do with the financial sector, is a far more difficult challenge. The Fed may have to buy stocks on the open market, a tactic that has been used by the Bank of Japan.

A whole family of bears.

• The Big Story: Edge Of The Cliff (RV/ZH)

Real Vision released a video early today containing interviews with some of the biggest names in the hedge fund universe. Though the interview was shot a few weeks ago, remarks from Hayman Capital’s Kyle Bass resonated with market’s mood. Bass discussed what he sees as the many short- and long-term risks to the US equity market, including the rise of algorithmic trading and passive investment, which have enabled investors to take risks without understanding what they’re doing, leaving the market vulnerable to an “air pocket.” And with so many traders short vol, Bass said investors will know the correction has begun when a 4% or 5% drop in equities snowballs into a 10% to 15% decline at the drop of a hat.

“The shift from active to passive means that risk is in the hands of people who don’t know how to take risk. Therefore we’re likely to have a 1987 air pocket. This is like portfolio insurance on steroids, the way algorithmic trading is now running the market place. Investors are moving from active to passive, meaning they’re taking the wheel themselves all at a time when CTAs are running their own algo strategies where they’re one and a half times long and half short and they all believe they can come out at the same time.” “If you see the equity market crack 4 or 5 points, buckle up, because I think we’re going to see a pretty interesting air-pocket, and I don’t think investors are ready for that,” Bass said.

“Our trade relationship with China is worsening our relationship with north korea whatever it is continually worsens. We’ve got three people at the head of these countries that are trying ot maike their countries great again, I think that’s a real risk geopolitically.” “But when you think about it financially, which is actually easier to calculate, the financial reason is the G-4 central banks going from a period of accommodation to a period of tightening, and that’s net of bond issuance.

Yeah, that’s right. We’re not issuing enough debt yet. What will central banks purchase?

• A $4 Trillion Hole in Bond Market May Start Filling in 2018 (BBG)

A key dynamic that’s been holding down bond yields since the global financial crisis is poised to ease next year – presenting a test to riskier parts of the market, according to analysis by Oxford Economics. In the aftermath of the crisis, banks and shadow financial institutions in developed economies sharply cut back their issuance of bonds, to the tune of about $4 trillion, according to the research group’s tally. That happened thanks to banks shrinking their balance sheets amid a regulatory crackdown, and due to a contraction in supply of mortgages that were regularly securitized into asset-backed bonds. “Against stable demand for fixed-income securities, the large negative supply shock created an increasingly acute shortage of these assets,” said Guillermo Tolosa, an economic adviser to Oxford Economics in London who has worked at the IMF.

The impact of that shock was an “almost decade-long yield squeeze,” he wrote. That compression “may start to ease in 2018,” Tolosa wrote in a report distributed Tuesday. Using slightly different metrics, the chart below shows how the market for financial company debt securities in the Group of Seven nations shrank after the 2009 global recession, and now appears to have flat-lined. Continued demand among mutual funds, pensions and insurance companies for fixed income then created the opportunity for nonfinancial companies to ramp up issuance, Tolosa wrote – a dynamic also seen in the chart. It’s one of a number of supply factors that have been identified explaining why bond yields globally remain historically low. Perhaps the most well documented one is the QE programs by the Fed, ECB and Bank of Japan that gobbled up about $14 trillion of assets.

Tolosa’s analysis suggests that Fed QE has had less of an impact than generally accepted, as the initiative was “more than offset” by increased public-sector borrowing. The large portfolio rebalancing in fixed income was instead “essentially a switch within private sector securities,” he said. There was a “massive shift” from financial securities into Treasuries, along with nonfinancial corporate and overseas debt, Tolosa concluded. “This explains a considerable part of the post-crisis surge in demand for other spread products and the issuance boom for global nonfinancial corporates and emerging-market borrowers,” Tolosa wrote. Over the decade through 2007, 10-year U.S. Treasury yields averaged 4.85%. But since the start of 2009 they’ve averaged just 2.46% – giving investors incentives to find higher rates elsewhere.

What’s in a number?

• US Fiscal Year Deficit Widens To $666 Billion (R.)

The U.S. budget deficit widened to $666 billion for the fiscal year 2017 as record spending more than offset record receipts, the Treasury Department said on Friday. The 2017 deficit increased to 3.5% of gross domestic product. The previous fiscal year deficit was $586 billion, with a deficit-to-GDP ratio of 3.2%. The latest fiscal year, which ended Sept. 30, straddled the presidencies of Barack Obama, a Democrat, and Donald Trump, a Republican. Accounting for calendar adjustments, the 2017 fiscal year deficit was $644 billion compared with $546 billion the prior year. Fiscal 2017 revenues increased 1% to $3.315 trillion, while spending rose 3% to $3.981 trillion. Since taking office in January, the Trump administration has sought to overhaul the U.S. tax code with precise details currently being worked on in Congress.

The Republican tax plan currently calls for as much as $6 trillion in tax cuts, which would sharply reduce government revenues. It has prompted criticism that it favors tax breaks for business and the wealthy and could add trillions of dollars to the deficit. The administration contends tax cuts will pay for themselves by boosting economic growth. In addition to the annual deficit, the national debt – the accumulation of past deficits and interest due to lenders to the Treasury – now exceeds $20 trillion. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has said the ever-rising debt levels are unsustainable as the government pays for the medical and retirement costs of the aging Baby Boomer generation.

We know they don’t know a thing.

• Fed’s Yellen Defends Past Policies As Trump Mulls Top Fed Pick (R.)

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen said on Friday that asset purchases and other unconventional policy tools must remain part of the Fed’s arsenal as long as the economy remains stuck in a low interest-rate economy. Yellen’s remarks offered a contrast between her legacy as Fed chair with the policy views of others who President Donald Trump is considering for her position when her term expires in February. Yellen told the National Economists Club, “We must keep our unconventional policy tools ready to be deployed again.” Reaching the near-zero lower bound would force the Fed to turn to other means to stimulate the economy. Following the 2007 to 2009 financial crisis, the Fed used both a spoken commitment to lower rates and $3.5 trillion in asset purchases to pull rates lower than they would have been otherwise, boosting consumption and growth.

Those asset holdings are now on the decline, the Fed’s policy rate is being increased, and the economy in general is doing well, Yellen said. But she cautioned that the world may not return to its old normal, and “future policymakers” may need to use emergency steps similar to those used in the past decade. Persistent low inflation has caught the Fed by surprise and is “of great concern,” Yellen said. She and other Fed officials are also convinced that the “neutral” rate, which neither stimulates nor discourages economic activity, is much lower than in the past, likely limiting how far the Fed can go during this rate increase cycle. As President Donald Trump mulls a switch at the Fed, Trump is considering several possible replacements for Yellen.

One of the possible nominees Trump has interviewed, former Fed Governor Kevin Warsh, was critical of Fed asset purchases at the time, and argued that Fed has stayed too deeply involved in asset markets. Another, Stanford Economist John Taylor, advocates use of an interest rate rule that would have recommended higher rates through the downturn and recovery. Once rates reach the lower bound, moreover, Taylor’s rule-based approach would likely have to give way to judgment about what steps to take.

What curious ideas.

• ‘Dr. Doom’, Marc Faber, Removed From More Boards After Comments On Race (R.)

Marc Faber, the markets prognosticator known as “Dr. Doom,” has been dismissed from three more company boards after comments in his latest newsletter this week suggested the United States had only prospered because it was settled by white people. U.S-based Sunshine Silver Mining, Vietnam Growth Fund managed by Dragon Capital, and Indochina Capital Corporation, had all dismissed him, Faber told Reuters on Friday, Faber has now been fired from six boards with Canadian fund manager Sprott, NovaGold Resources and Ivanhoe Mines letting him go on Tuesday after his remarks went viral on social media platform Twitter. In the October edition of his newsletter, “The Gloom, Boom & Doom Report,” in a section discussing capitalism versus socialism, Faber criticized the move to tear down monuments commemorating the U.S. Civil War military leaders of the Confederacy.

“Thank God white people populated America, not the blacks,” Faber wrote in his newsletter. “Otherwise, the U.S. would look like Zimbabwe, which it might look like one day anyway, but at least America enjoyed 200 years in the economic and political sun under a white majority.” “I am not a racist,” Faber continued, “but the reality – no matter how politically incorrect – needs to be spelled out as well.” Faber, a Swiss investor based in Thailand, who oversees $300 million in assets, said he has not lost any client money, and still stands by his comments and will keep publishing his newsletter. ”My clients all know me for more than 30 years. They know that to call me a racist is inappropriate,” he said. Faber said he has not seen a significant amount of subscribers cancel their subscriptions to his newsletter as a result of the controversy. “No, I think most people actually agree with me and certainly defend freedom of expression even if it does not coincide with their views.”

Strange indeed.

• China Still Needs Loans From World Bank (Caixin)

The World Bank’s former country director for China has defended the organization’s lending to Chinese governments. Yukon Huang, who now serves as a senior fellow at the Carnegie Asia Program, made the remarks after reports said the U.S. has rejected a capital increase plan for the multilateral lender because of dissatisfaction with its loans to wealthier countries, including China. The provincial-level and local governments need the World Bank loans because structural impediments prevent domestic banks from providing sufficient credit to finance public projects, Huang said. Chinese governments that borrow from the World Bank benefit from the support, Huang told Caixin. For example, he said, loans help agencies finance public services without having to rely so much on land sale revenues.

World Bank loans also help those governments improve their debt management. World Bank funds made available in January through its Development Policy Financing program are now helping governments within Hunan province and the municipality of Chongqing “achieve fiscal sustainability through a comprehensive and transparent public finance framework that integrates budget, public investment and debt management,” according to a statement on the World Bank’s website. For two years, the World Bank Group had been working to get member countries to agree on a capital increase plan for its International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) lending arm before the 2017 World Bank and IMF annual meetings, which began last week, according to Reuters.

The IBRD, the world’s largest development bank, is dedicated to helping countries reduce poverty and extending the benefits of sustainable growth by providing them with financial products and policy advice, its official website says. The U.S. is currently the largest IBRD shareholder out of its 189 member nations, with the greatest voting power of 16.28%. China is the third-largest shareholder, after Japan, with 4.53% voting power. The Trump administration was reluctant to endorse the capital increase, with U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin saying in an Oct. 13 statement that “more capital is not the solution when existing capital is not allocated effectively.” “We want to see a significant shift in allocation of funding to support countries most in need of development finance,” Mnuchin said.

Yes, Italy’s troubles run deep.

• Betrayed by Banks, 40,000 Italian Businesses Are in Limbo (BBG)

The Most Serene Republic, as the area around Venice was known for a millennium, is now the troubled epicenter of a banking meltdown that’s threatening to derail one of globalization’s great success stories. The base of brands like Benetton, De’Longhi, Geox and Luxottica, Veneto has also become home to as many as 40,000 small businesses suddenly stranded without access to financing since a pair of regional banks collapsed in June. The implosions of Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca, which also wiped out the life savings of many of their 200,000 shareholders, set off economic and political tremors felt from Rome to Frankfurt. Anger over what many view as lax oversight by national authorities is animating a movement for more autonomy that’s already emboldened by Catalonia’s efforts to split from Spain.

“The pain for Veneto’s banks may be over, but the pain for Veneto’s businesses is just beginning,” said Andrea Arman, a lawyer advising some of the companies and individuals who’ve been hit the hardest. “We’re just starting to see the consequences of the collapse and what we’re seeing is alarming.” Nestled between the Alps and the Adriatic, Veneto is home to about 5 million people. Like Catalonia, it has a seafaring heritage, its own language and incomes far above the national average. Veneto President Luca Zaia, who’s called Italy and its 64 governments in 71 years a “bankrupt state,” plans to use the results of a nonbinding referendum on Oct. 22 to press Rome for more autonomy. Three out of four Veneti want more local power and 15% would support complete independence, according to a Demos poll published by La Repubblica this week.

While Intesa Sanpaolo SpA, Italy’s second-largest bank, paid a symbolic sum to acquire the healthiest parts of the two Veneto lenders, the state entity that’s absorbing the 18 billion euros ($21.3 billion) of troubled debt the banks amassed, called SGA, isn’t fully operational yet. That has left small and midsized companies in the lurch—in many cases unable to do business. “Many of these borrowers are profitable companies, but they’re stuck in limbo,” said Mauro Rocchesso, head of Fidi Impresa e Turismo Veneto, a financial firm that provides collateral to companies seeking lines of credit. “They don’t have a counterparty anymore and can’t find fresh capital from a new lender because of their exposure to the two Veneto banks.”

More violence and Rajoy is out.

• Catalan Rebels Say Spain Will Live to Regret Hostile Power Grab (BBG)

Catalan separatists say Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy doesn’t know what he’s getting himself into as he moves to quash their campaign for independence. As the government in Madrid prepares to deploy its most powerful legal weapons, three leading members of the movement in Barcelona said Rajoy isn’t equipped to achieve his goals and risks a damaging entanglement in hostile terrain. They reckon they have enough support among the Catalan civil service and police to thwart Spain’s plan. Rajoy’s cabinet meets in Madrid on Saturday to consider specific measures to reassert control over the rebel region, a process set out in the Spanish Constitution that’s never yet been tested. Among the top priorities is bringing to heel the Catalan police force and deciding what to do with President Carles Puigdemont.

The plan still needs approval by the Senate, so it could be another two weeks before Spain can take any action. “This is a minefield for Rajoy,” said Antonio Barroso, an analyst in London at Teneo Intelligence, a company advising on political risk. “The implementation on the ground is a risk for him when the government may face some regional civil servants who don’t cooperate.” The three Catalan officials – one from the parliament, one from the regional executive and one from the grass-roots campaign organization – spoke on condition of anonymity due to the legal threats against the movement. It all comes down to Article 155 of the constitution, a short passage that gives the legal green light for Spain to revoke the semi-autonomy of Catalonia. Foreign Minister Alfonso Dastis said at a press conference in Madrid on Friday that it would be applied in a “prudent, proportionate and gradual manner.”

The problem for Rajoy is that the separatists already proved with their makeshift referendum on Oct. 1 that they can ignore edicts from Madrid with a degree of success. That means he will need to back up his ruling with people on the ground, and it didn’t work as planned the last time around. The Catalan police force, the Mossos d’Esquadra, ignored orders to shut down polling stations before the illegal vote on Oct. 1. After Rajoy sent in the Civil Guard, images of Spanish police beating would-be voters were broadcast around the world. Mossos Police Chief Josep Lluis Trapero is a local hero, his face worn on T-shirts at separatist demonstrations. When he returned this week from an interrogation in Madrid, where he’s facing possible sedition charges, staff greeted him with hugs and applause.

And we worry about a financial apocalypse. If you value money over life, you will lose both.

• A Giant Insect Ecosystem Is Collapsing Due To Humans. It’s A Catastrophe (G.)

They are multitudinous almost beyond our imagining. They thrive in soil, water, and air; they have triumphed for hundreds of millions of years in every continent bar Antarctica, in every habitat but the ocean. And it is their success – staggering, unparalleled and seemingly endless – which makes all the more alarming the great truth now dawning upon us: insects as a group are in terrible trouble and the remorselessly expanding human enterprise has become too much, even for them. The astonishing report highlighted in the Guardian, that the biomass of flying insects in Germany has dropped by three quarters since 1989, threatening an “ecological Armageddon”, is the starkest warning yet; but it is only the latest in a series of studies which in the last five years have finally brought to public attention the real scale of the problem.

Does it matter? Even if bugs make you shudder? Oh yes. Insects are vital plant-pollinators and although most of our grain crops are pollinated by the wind, most of our fruit crops are insect-pollinated, as are the vast majority of our wild plants, from daisies to our most splendid wild flower, the rare and beautiful lady’s slipper orchid. Furthermore, insects form the base of thousands upon thousands of food chains, and their disappearance is a principal reason why Britain’s farmland birds have more than halved in number since 1970. Some declines have been catastrophic: the grey partridge, whose chicks fed on the insects once abundant in cornfields, and the charming spotted flycatcher, a specialist predator of aerial insects, have both declined by more than 95%, while the red-backed shrike, which feeds on big beetles, became extinct in Britain in the 1990s. Ecologically, catastrophe is the word for it.

[..] It seems indisputable: it is us. It is human activity – more specifically, three generations of industrialised farming with a vast tide of poisons pouring over the land year after year after year, since the end of the second world war. This is the true price of pesticide-based agriculture, which society has for so long blithely accepted. So what is the future for 21st-century insects? It will be worse still, as we struggle to feed the nine billion people expected to be inhabiting the world by 2050, and the possible 12 billion by 2100, and agriculture intensifies even further to let us do so. You think there will be fewer insecticides sprayed on farmlands around the globe in the years to come? Think again. It is the most uncomfortable of truths, but one which stares us in the face: that even the most successful organisms that have ever existed on earth are now being overwhelmed by the titanic scale of the human enterprise, as indeed, is the whole natural world.