DPC City Market, Kansas City, Missouri 1906

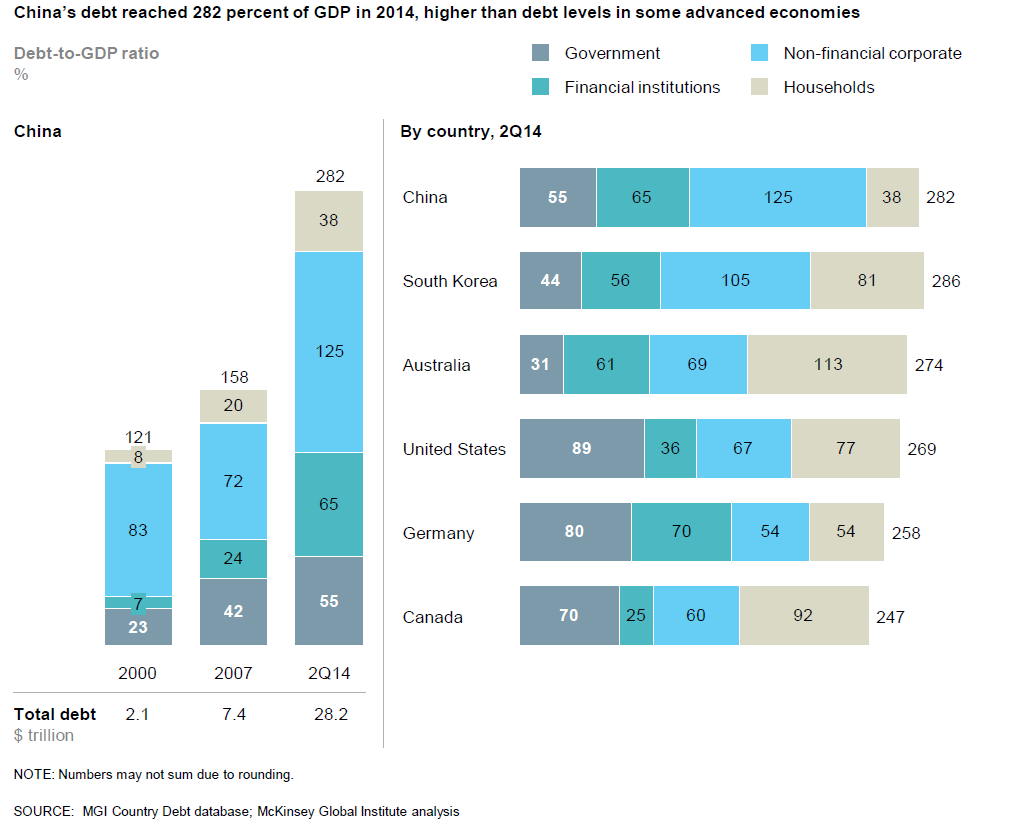

“Thanks to real estate and shadow banking, debt in the world’s second-largest economy has quadrupled from $7 trillion in 2007 to $28 trillion in the middle of last year.”

• A World Overflowing With Debt (Bloomberg)

The world economy is still built on debt. That’s the warning today from McKinsey’s research division which estimates that since 2007, the IOUs of governments, companies, households and financial firms in 47 countries has grown by $57 trillion to $199 trillion, a rise equivalent to 17 percentage points of gross domestic product. While not as big a gain as the 23 point surge in debt witnessed in the seven years before the financial crisis, the new data make a mockery of the hope that the turmoil and subsequent global recession would put the globe on a more sustainable path. Government debt alone has swelled by $25 trillion over the past seven years and developing economies are responsible for almost half of the overall gain.

McKinsey sees little reason to think the trajectory of rising leverage will change any time soon. Here are three areas of particular concern:

1. Debt is too high for either austerity or growth to cure. Politicians will instead need to consider more unorthodox measures such as asset sales, one-off tax hikes and perhaps debt restructuring programs.

2. Households in some nations are still boosting debts. 80% of households have a higher debt than in 2007 including some in northern Europe as well as Canada and Australia.

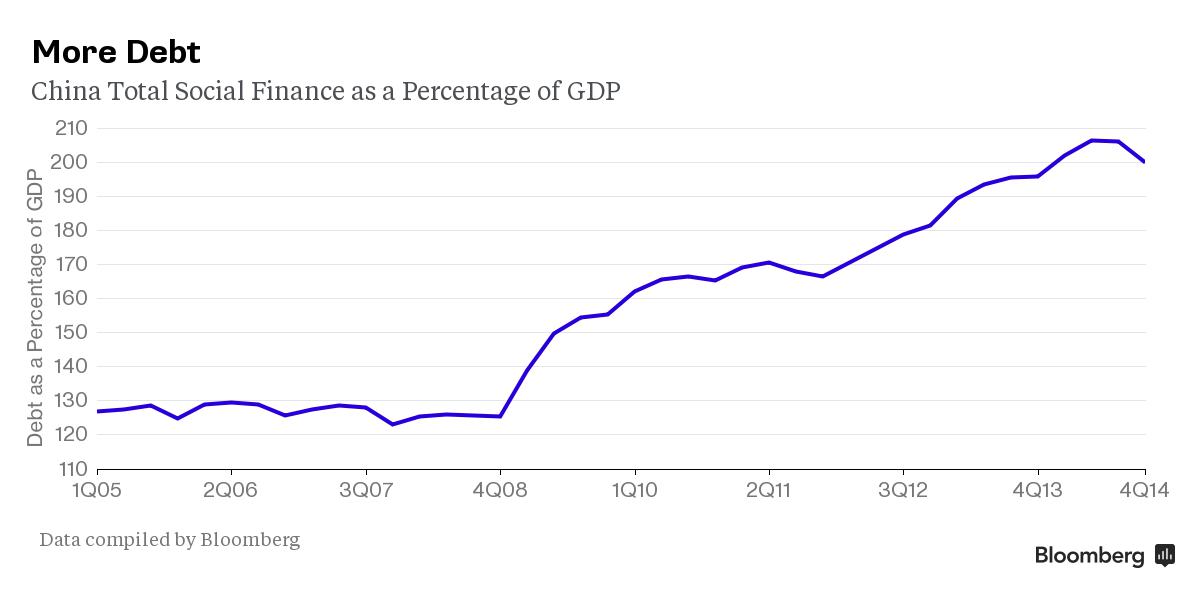

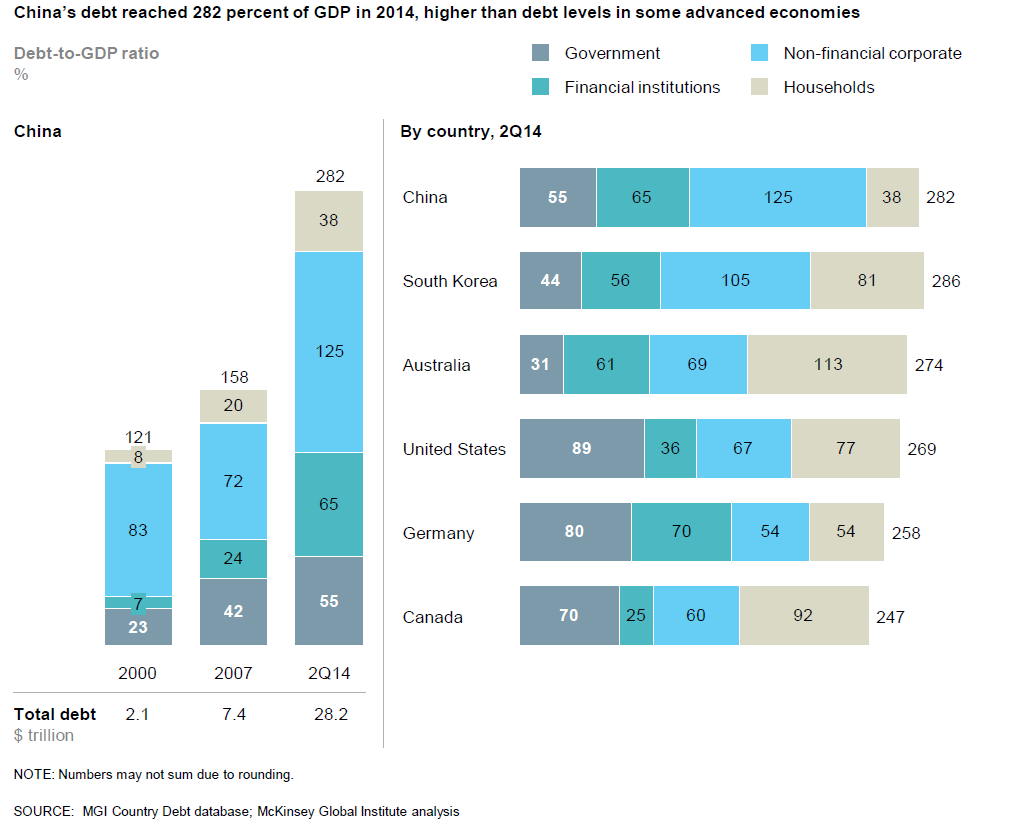

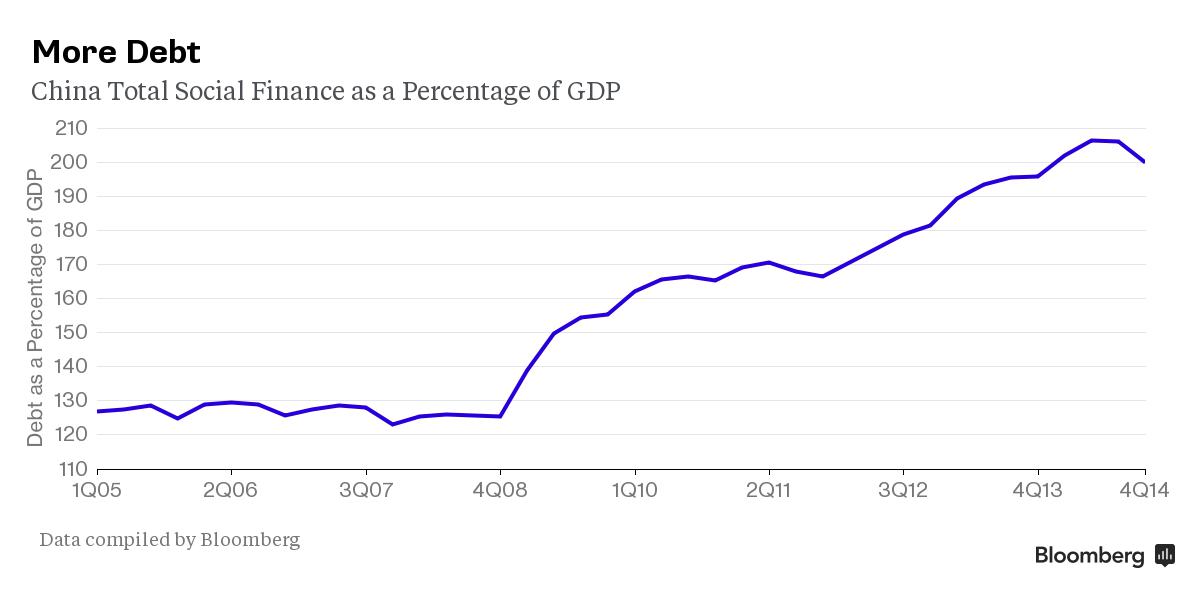

3. China’s debt is rising rapidly. Thanks to real estate and shadow banking, debt in the world’s second-largest economy has quadrupled from $7 trillion in 2007 to $28 trillion in the middle of last year. At 282% of GDP, the debt burden is now larger than that of the U.S. or Germany. Especially worrisome to McKinsey is that half the loans are linked to the cooling property sector.

Read more …

“..the US is adamantly opposed; perhaps it wants to reinstitute debtor prisons for over indebted countries’ officials (if so, space may be opening up at Guantánamo Bay)..”

• A Greek Morality Tale: We Need A Global Debt Restructuring Framework (Stiglitz)

Given the amount of distress brought about by excessive debt, one might well ask why individuals and countries have repeatedly put themselves into this situation. After all, such debts are contracts – that is, voluntary agreements – so creditors are just as responsible for them as debtors. In fact, creditors arguably are more responsible: typically, they are sophisticated financial institutions, whereas borrowers frequently are far less attuned to market vicissitudes and the risks associated with different contractual arrangements. Indeed, we know that US banks actually preyed on their borrowers, taking advantage of their lack of financial sophistication.

At the international level, we have not yet created an orderly process for giving countries a fresh start. Since even before the 2008 crisis, the UN, with the support of almost all of the developing and emerging countries, has been seeking to create such a framework. But the US is adamantly opposed; perhaps it wants to reinstitute debtor prisons for over indebted countries’ officials (if so, space may be opening up at Guantánamo Bay). The idea of bringing back debtors’ prisons may seem far-fetched, but it resonates with current talk of moral hazard and accountability. There is a fear that if Greece is allowed to restructure its debt, it will simply get itself into trouble again, as will others. This is sheer nonsense. Does anyone in their right mind think that any country would willingly put itself through what Greece has gone through, just to get a free ride from its creditors?

If there is a moral hazard, it is on the part of the lenders – especially in the private sector – who have been bailed out repeatedly. If Europe has allowed these debts to move from the private sector to the public sector – a well-established pattern over the past half-century – it is Europe, not Greece, that should bear the consequences. Indeed, Greece’s current plight, including the massive run-up in the debt ratio, is largely the fault of the misguided troika programs foisted on it. So it is not debt restructuring, but its absence, that is “immoral”. There is nothing particularly special about the dilemmas that Greece faces today; many countries have been in the same position. What makes Greece’s problems more difficult to address is the structure of the eurozone: monetary union implies that member states cannot devalue their way out of trouble, yet the modicum of European solidarity that must accompany this loss of policy flexibility simply is not there.

Read more …

“The average one-year borrowing cost for Chinese companies has risen from zero to 5% in real terms over the past three years..”

• Devaluation By China Is The Next Great Risk For A Deflationary World (AEP)

China is trapped. The Communist authorities have discovered, like the Japanese in the early 1990s and the US in the inter-war years, that they cannot deflate a credit bubble safely. A year of tight money from the People’s Bank and a $250bn crackdown on shadow banking have pushed the Chinese economy close to a debt-deflation crisis. Wednesday’s surprise cut in the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) – the main policy tool – comes in the nick of time. Factory gate deflation has reached -3.3%. The official gauge of manufacturing fell below the “boom-bust” line to 49.8 in January. Haibin Zhu, from JP Morgan, says the 50-point cut in the RRR from 20% to 19.5% injects roughly $100bn into the system. This will not, in itself, change anything. The average one-year borrowing cost for Chinese companies has risen from zero to 5% in real terms over the past three years as a result of falling inflation.

UBS said the debt-servicing burden for these firms has doubled from 7.5% to 15% of GDP. Yet the cut marks an inflection point. There will undoubtedly be a long series of cuts before China sweats out its hangover from a $26 trillion credit boom. Debt has risen from 100% to 250% of GDP in eight years. By comparison, Japan’s credit growth in the cycle preceding its Lost Decade was 50% of GDP. The People’s Bank may have to cut all the way to zero in the end – a $4 trillion reserve of emergency oxygen – but to do that is to play the last card. Wednesday’s trigger was an amber warning sign in the jobs market. The employment component of the manufacturing survey contracted for the 15th month. Premier Li Keqiang targets jobs – not growth – and the labour market is looking faintly ominous for the first time.

Unemployment is supposed to be 4.1%, a make-believe figure. A joint study by the IMF and the International Labour Federation said it is really 6.3%, high enough to cause sleepless nights for a one-party regime that depends on ever-rising prosperity to replace the lost elan of revolutionary Maoism. Whether or not you call it a hard-landing, China is struggling. Home prices fell 4.3% in December. New floor space started has slumped 30% on a three-month basis. This packs a macro-economic punch. A study by Jun Nie and Guangye Cao for the US Federal Reserve said that since 1998 property investment in China has risen from 4% to 15% of GDP, the same level as in Spain at the peak of the “burbuja”. The inventory overhang has risen to 18 months compared with 5.8 in the US.

The property slump is turning into a fiscal squeeze since land sales make up 25% of local government money. Zhiwei Zhang, from Deutsche Bank, says land revenues crashed 21% in the fourth quarter of last year. “The decline of fiscal revenue is the top risk in China and will lead to a sharp slowdown,” he said. The IMF says China’s fiscal deficit is nearly 10% of GDP once land sales are stripped out and all spending included, far higher than generally supposed. It warned two years ago that Beijing was running out of room and could ultimately face “a severe credit crunch”.

Read more …

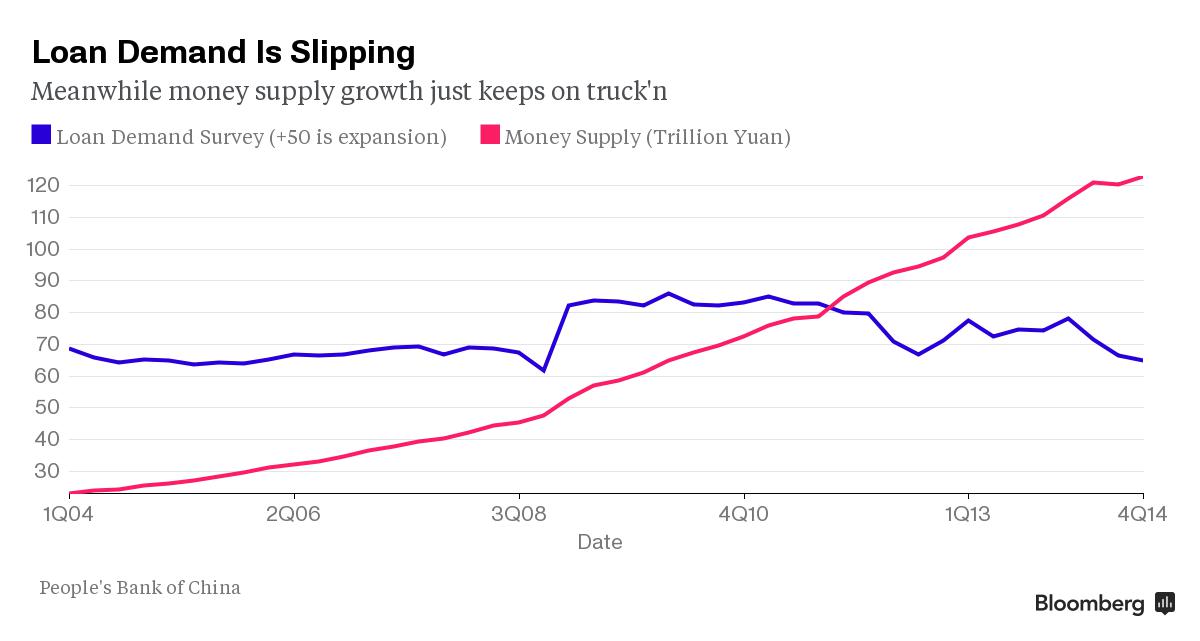

“The obsession with monetary policy is a problem around the world, but only China has a money supply of $20 trillion.”

• Pushing on a String? Two Charts Showing China’s Dilemma (Bloomberg)

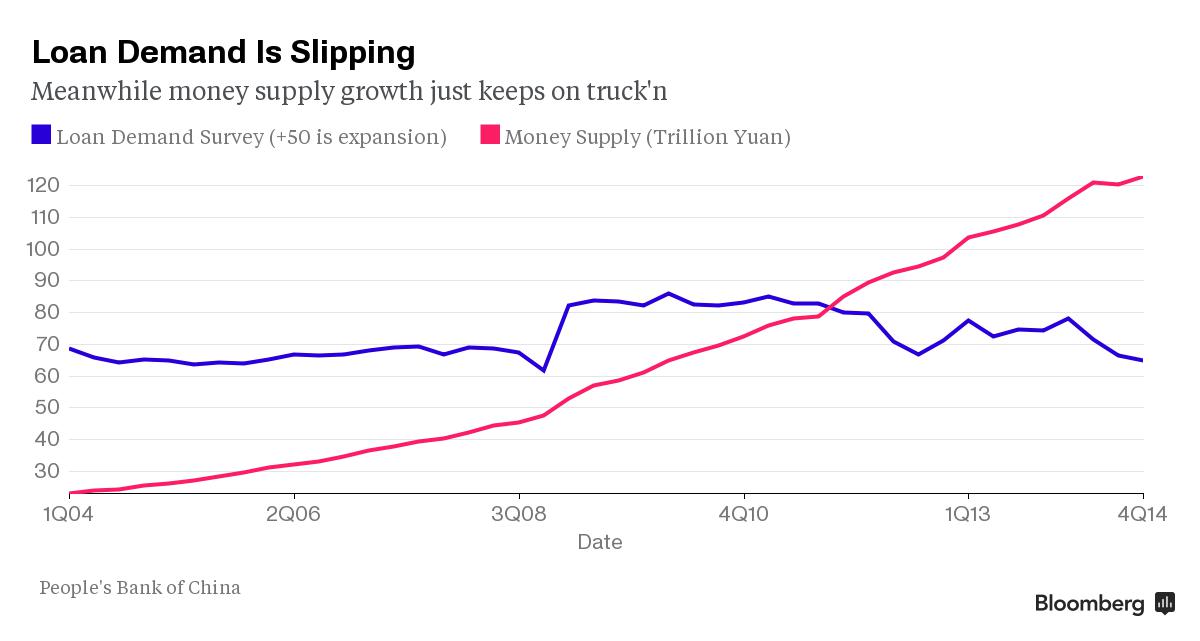

Is China’s latest monetary easing really going to help? While economists see it freeing up about 600 billion yuan ($96 billion), that assumes businesses and consumers want to borrow. This chart may put some champagne corks back in. It shows demand for credit is waning even as money supply continues its steady climb.

The reserve ratio requirement cut “helps to raise loan supply, but loan demand may remain weak,” said Zhang Zhiwei, chief China economist at Deutsche Bank. “We think the impact on the real economy is positive, but it is not enough to stabilize the economy.” This chart may also give pause. It shows the surge in debt since 2008, which has corresponded with a slowdown in economic growth.

“Monetary stimulus of the real economy has not worked for several years,” said Derek Scissors, a scholar at the American Enterprises Institute in Washington who focuses on Asia economics. “The obsession with monetary policy is a problem around the world, but only China has a money supply of $20 trillion.”

Read more …

Brazil is falling to bits. The Olympics next year will be the focus of mass protests, much bigger than last year’s.

• Petrobras, Now $262 Billion Poorer, Exposes Busted Brazil Dream (Bloomberg)

When Brazil emerged from the global financial crisis as one of the world’s great rising powers, Petrobras was the symbol of that growing economic might. The state-run oil giant was embarking on a $220 billion investment plan to develop the largest offshore crude discovery in the Western hemisphere since 1976 and was, in the words of then-President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the face of “the new Brazil.” Today the company epitomizes everything that is wrong with a Brazilian economy that has been sputtering for the better part of four years: It’s mired in a corruption scandal that cost the CEO her job this week; it has failed to meet growth targets year after year; and it’s saddling investors with spectacular losses. Once worth $310 billion at its peak in 2008, a valuation that made it the world’s fifth-largest company, Petroleo Brasileiro SA is today worth just $48 billion.

While Brazil’s decline on the international stage has been playing out since the commodities-driven economic boom first began to fizzle in 2011, the corruption case at Petrobras deepens the growing sense of crisis in the South American country. The government is posting record budget deficits after a collapse in prices for the soy, oil and iron that the nation exports; Sao Paulo is running out of water amid the biggest drought in decades; and the real dropped the most among major currencies in the past six months. “Brazil seemed great during close to 10 years of rising commodity prices and a very positive terms of trade,” Jim O’Neill, the former Goldman chief economist who coined the BRIC acronym, said. “It disguised lots of underlying problems and of course it made policy makers lazy and allowed bad behavioral habits to go on, as this Petrobras story epitomizes.”

It wasn’t supposed to go like this. In the halcyon days, the country was awarded rights to host the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 summer Olympics. The nation was in the midst of the kind of economic expansion it hadn’t seen in decades, posting growth of more than 5% in three out of four years. To understand how far Brazil has fallen since, compare the markets’ performance under Lula with that of his protege and successor, Dilma Rousseff. Lula oversaw a 113% rally in the real, the best-performing emerging-market currency during his years in office from 2003 through 2010. A commodity surge also helped stocks reach their peak during his last year in office after the benchmark Ibovespa gauge jumped six-fold. Since the 67-year-old Rousseff took office in 2011 after serving as Lula’s energy minister and chief of staff, positions that also put her atop the board at Petrobras, the Ibovespa has lost about a third of its value and the currency sank about 40%.

Read more …

Take your pick. The race to the bottom is on.

• Central Bank Surprises: Who’s Next? (CNBC)

From Switzerland to Singapore, central banks around the world kept markets on their toes with unexpected policy moves January, and economists say the surprises aren’t going to stop there. Last month alone, central banks in India, Egypt, Peru, Denmark, Canada and Russia announced surprise interest rate cuts. This came alongside Switzerland’s unanticipated decision to scrap its three-year-old cap on the franc and Singapore’s off-cycle move to tweak its exchange rate policy in order to ease the rise of the local currency. On Wednesday, the People’s Bank of China surprised markets on Wednesday by cutting the reserve requirement ratio (RRR) by 50 basis points to 19.5% – its first country-wide RRR cut since May 2012. “We expect more central banks to surprise with either the timing or size of any monetary policy easing,” said Rob Subbaraman, chief economist and head of global markets research, Asia ex-Japan at Nomura.

Within Asia, central banks in China, Thailand, Korea, India, Indonesia and Singapore are the ones to watch, he said. The backdrop of disinflationary pressures, a slowing China, and faltering exports may force central banks to act off-cycle, Subbaraman said. These dynamics have become increasingly clear in the past couple of months. “Thailand has recently joined Singapore in outright CPI (consumer price index) deflation; Korea, excluding the one-off tobacco price hike, is very close to deflation, as is Taiwan. Most other countries are facing low-flation or steep declines in inflation,” he said, citing India and Indonesia. Meanwhile, economic powerhouse China, a key source of demand for smaller economies in the region, started the year on a sluggish note. The country’s Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) data for January signaled the manufacturing sector is once again losing steam.

The government’s official PMI dipped into contractionary territory for the first time in two and the half years, coming in at 49.8 and surprising market watchers who were expecting expansion. Finally, Asia’s export engine appears to be sputtering. Korea – the first country in Asia to release January trade data – saw exports shrink 0.4% on year in January. In China, following Wednesday’s surprise move, Subbaraman expects 50 basis point RRR cuts in each of the remaining quarters of 2015 and a 25 basis point interest rate cut in the second quarter. In Korea, where he expects the central bank to cut interest rates by 25 basis points in April and July, there’s a risk they could come earlier. In India, where he expects only one more 25 basis point rate cut this year – in April – there’s a chance there could be more.

Read more …

The fall of emerging markets, rather than Greece, is set to be the final nail in the euro’s coffin.

• There’s Nothing Left To Break The Euro’s Fall Now (MarketWatch)

The euro remained weak against rival currencies during the Asian session Thursday, weighed down by renewed risk aversion stemming from the ECB’s tougher stance on Greece. The euro hit as low as $1.1304 – close to its 11-year low – before stabilizing at $1.1354 around 0540 GMT. That was weaker than $1.1391 late Wednesday in New York. The common currency also fell as low as ¥132.57 before bouncing back to ¥133.18. That compares with ¥133.56 late in New York. “Because of the quantitative easing (by the ECB) in the first place, I don’t have a feeling that the (euro’s) move to break below $1.1 has stopped,” said Koji Fukaya, chief executive of FPG Securities. “I don’t see any incentives that can help prevent the euro’s fall,” he also said. Earlier in the session, the single currency lost ground following the news that the ECB would suspend a waiver it had extended to Greek public securities used as collateral by the country’s financial institutions for central bank loans.

Greece’s new finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, softened a hardline tone on debt repayments during a whirlwind tour of Europe this week. But tough negotiations remain and a deal is far from certain. Because Greek government bonds are junk rated, and thus below the ECB’s minimum threshold, Greek banks have relied on a waiver to post collateral for cheap ECB financing through the central bank’s regular facilities. The ECB is suspending that waiver. The headline raised concerns about Greek banks’ fundraising ability at the time when investors are keen to monitor negotiations between Greece and its international creditors on a €240 billion bailout plan. But the euro managed to stay above the $1.13 threshold as investors became aware that Greek banks will still have access to funds through the ECB’s emergency lending program. Under that facility, the credit risk of the loans stays on the books of the Greek central bank, and the loans carry a higher interest rate.

Read more …

“..the commitment to European solidarity, invoked down the years to motivate the whole project, has all but vanished. Far from thinking “we’re in this thing together,” Germany sees Greece as a nation of scroungers and thieves, and Greece sees Germany as a nation of atavistic oppressors..”

• Will the Next Recession Destroy Europe? (Bloomberg)

As things stand, the policy options would be limited. Interest rates are already at zero. Notwithstanding QE, the ECB is a more inhibited central bank than, say, the U.S. Federal Reserve. It’s forbidden to undertake direct monetary financing of governments. On QE, it finally decided to test the limits of that prohibition, but more effective forms of monetary-base expansion – such as so-called helicopter money – are seen as expressly forbidden. Fiscal stimulus, on the other hand, is ruled out by the sinister combination of institutional incapacity and mutual animosity. To be sure, the euro area as a whole isn’t lacking in fiscal capacity.

Euro-area government debt is less than U.S. public debt. There’s no economic reason why Europe shouldn’t borrow (at extremely low interest rates) and spend the money on, say, large-scale infrastructure investments. But when Europe designed its monetary union it forgot to design even the rudimentary fiscal union that, as we’ve learned, the larger enterprise needs. Then why not start building such a union? Partly because it would require a new European treaty, which in turn would demand a measure of popular consent. With the union and its works so unpopular, governments dread embarking on that process.

More fundamentally, the commitment to European solidarity, invoked down the years to motivate the whole project, has all but vanished. Far from thinking “we’re in this thing together,” Germany sees Greece as a nation of scroungers and thieves, and Greece sees Germany as a nation of atavistic oppressors. Unless this failing union is reshaped in far-reaching ways, the optimistic scenario is protracted stagnation. The pessimistic scenario is political collapse, followed by who knows what. Where are the European leaders willing to rise to this challenge? Name me any who’ve even begun to think about it.

Read more …

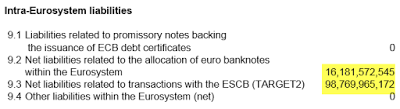

“Greek banks will be able to tap funds through a program known as emergency liquidity assistance, or ELA. Under the program, the loans are more expensive and remain on the books of Greece’s central bank rather than the ECB.”

• What You Need To Know About ECB’s Greek Collateral Decision (MarketWatch)

The European Central Bank just cranked up the pressure on Greece’s new antiausterity government as it attempts to renegotiate the terms of its bailout, telling Athens that Greek banks can no longer use the country’s sovereign debt as collateral for ECB-provided liquidity. U.S. stocks fell in late trade after the headlines hit and the euro extended a drop versus the U.S. dollar. Here’s what you need to know:

What did the ECB just do? The ECB’s Governing Council suspended a waiver that had allowed Greek banks to use the country’s junk-rated government bonds as collateral for central bank loans.

Why did the ECB do it? Greek bonds are junk rated, thus the waiver was needed to allow the banks to post collateral that could be used for cheap funding from the ECB. One of the prerequisites for the waiver was that Greece remain in compliance with a bailout program. In its decision, the ECB said it pulled the plug on the waiver because it can’t be sure that Greece’s attempts to secure a new program will be successful. Beyond the official reasons, the move is seen as a definitive warning that, like Germany, the ECB is in no mood to give in to Athens’s request for a debt swap. News reports also indicated the ECB isn’t open to requests to allow Greece to raise short-term cash by issuing additional Treasury bills in an effort to keep the government funded as it attempts to reach a new deal with its creditors.

Where does that leave Greek banks? It’s not a welcome development. Greek banks have suffered significant deposit withdrawals before and after the January election that brought the antiausterity government, led by Syriza’s Alexis Tsipras, to power. “This news will likely scare depositors and result in further bank runs,” said Peter Boockvar at the Lindsey Group. “This all said, if Greece can come to an agreement with the troika, I’m sure the ECB will reinstate the waiver,” Boockvar added. While the kneejerk reaction in markets has been negative, analysts note that junk-rated Greek sovereign debt made up a relatively small portion of the collateral used by Greek banks in funding operations as of the end of last year.

Karl Whelan, economics professor at University College Dublin, recently estimated that Greek banks were using a maximum of €8 billion in Greek government debt as collateral for loans from the Eurosystem as of December versus total loans of €56 billion. Meanwhile, the ECB said Greek banks will be able to tap funds through a program known as emergency liquidity assistance, or ELA. Under the program, the loans are more expensive and remain on the books of Greece’s central bank rather than the ECB.

Read more …

” Its aim is “coming up with a European policy that will definitively put an end to the now self-perpetuating crisis of the Greek social economy.“

• Greece Sticks to Anti-Austerity Demands Following ECB Loan Cut (Bloomberg)

Greece held fast to demands to roll back austerity as the European Central Bank turned up the heat before Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis meets one of his main antagonists, German counterpart Wolfgang Schaeuble. The encounter at 12:30 p.m. in Berlin comes hours after Greece lost a critical funding artery when the ECB restricted loans to its financial system. That raised pressure on the 10-day-old government to yield to German-led austerity demands to stay in the euro zone. The government “remains unwavering in the goals of its social salvation program, approved by the vote of the Greek people,” according to a Finance-Ministry statement issued overnight. Its aim is “coming up with a European policy that will definitively put an end to the now self-perpetuating crisis of the Greek social economy.”

The next move is up to Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, who swept to power promising to reverse five years of spending cuts that accompanied €240 billion of bailout loans. While he’s retreated from demands for a debt writedown, he’s so far sticking to promises to increase pensions and wages that breach the conditions for financial aid. He’s scheduled to meet with his lawmakers in Athens around midday as parliament convenes. Greek securities fell after the ECB statement. The Global X FTSE Greece 20 ETF of Greek stocks plunged 10.4% in New York trading. Ten-year bonds declined, driving the yield up 70 basis points to 10.4%. The ECB’s decision, announced at 9:36 p.m. Wednesday in Frankfurt, will raise financing costs for Greek banks and stiffen oversight by the central bank. Greece’s Finance Ministry said the decision doesn’t reflect any negative developments in the financial sector and that banks are “adequately capitalized and fully protected.”

The ECB hadn’t publicly signaled that it would take such action so soon. On Jan. 8, the central bank said it would continue the waiver on the assumption that Greece would conclude a review of its current bailout program, which expires Feb. 28, and negotiate another one. A Bank of Greece spokesman said that liquidity will continue as normal, as existing ECB financing will be converted into Emergency Liquidity Assistance, or ELA. The official asked not to be named in line with policy and declined to answer all other questions. ELA is priced at an annual interest rate of 1.55% compared with the current ECB refinancing rate of 0.05%, Bank of Greece Governor Yannis Stournaras said in November. “You have to keep in mind that the Greek banking system used the ELA very extensively in 2012,” Steven Englander at Citigroup said. “So it’s not going beyond break. It’s a warning signal that the patience isn’t infinite.”

Read more …

An entirely different interpretation.

• Greek Finance Ministry Says ECB Decision Aimed At Eurogroup (Kathimerini)

The Greek Finance Ministry interpreted a European Central Bank decision to stop accepting Greek government bonds as collateral from local lenders as a moved aimed at pushing Athens and its eurozone partners towards a new debt deal. “By taking and announcing this decision, the European Central Bank is putting pressure on the Eurogroup to move quickly to seal a new mutually beneficial deal between Greece and its partners,” said the ministry in a statement released early on Thursday. The ministry insisted that the ECB’s decision, which means Greek lenders will have to revert to borrowing via the more expensive Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) provided by the Bank of Greece, did not reflect any concerns about the health of the local banking system.

“According to the ECB itself, the Greek banking system remains adequately capitalized and fully protected through its access to ELA,” said the statement. The Finance Ministry also indicated that the central bank’s decision would not change the government’s negotiating strategy. “The government is widening the scope of its negotiations with partners and institutions it belongs to each day,” it said. “It remains focussed on the targets of its social relief program, which the Greek people approved with their vote. It is negotiating with the aim of drafting of a European policy that would stop once and for all the self-feeding crisis of the Greek social economy.”

Read more …

“..the move from the ECB should have very little immediate effect on the Greek banks – provided there is not a complete loss of confidence..”

• What the ECB’s Move on Greek Government Debt Is Really All About (Bloomberg)

In a press release that jolted the markets, the ECB announced it will no longer accept Greek government debt as collateral starting next week. But this news is not necessarily a potential liquidity disaster for Greek banks. The Greek banking system is not particularly reliant on Greek sovereign debt as collateral. Figures from the Bank of Greece show that Greek financial institutions currently have about €21 billion of Greek sovereign exposure. Furthermore, this debt has already been subject to valuation haircuts of up to 40% when used as collateral at the ECB. All collateral that the Greek banks use for ECB operations that is not Greek sovereign debt is still perfectly good to use. This decision of the ECB is against the Greek sovereigns, not the Greek banks. Further, any shortfall in liquidity will be fully made up by Emergency Liquidity Assistance that will be issued by the Greek central bank at its own risk.

So, all together, the move from the ECB should have very little immediate effect on the Greek banks – provided there is not a complete loss of confidence in the Greek banking system in the coming days – and should be viewed as what it is: The ECB is pressuring the Greek government. Greece’s finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, has been agitating for Greek debt relief since his appointment after January’s election. Today the ECB gave its answer to his moves. If the Greek government does not agree to reenter a program, the ECB will not allow its debt to be used as collateral. The immediate effects should be seen as limited to the debt market but huge within the political realm. The ECB has often been accused of placing too much political pressure on governments. Today’s moves shows that it has chosen to ignore those accusations once again and do what it feels is right.

Read more …

Pre ECB decision.

• Greek Bill-Sale Demand Slumps as Nation Seeks New Debt Deal (Bloomberg)

Demand for Greece’s Treasury bills slumped to a more-than eight-year low at a sale Wednesday as the government struggles to strike a new bailout deal and avert a funding shortage. The nation sold €812.5 million of six-month bills, with an average yield of 2.75%, the Athens-based Public Debt Management Agency said. The bid-to-cover ratio, which gauges demand by comparing total bids with the amount of securities allotted, fell to 1.3, the least since July 2006. Greece has 947 million euros of debt coming due on Feb. 6. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras risks a liquidity crunch if he fails to cut a new deal on repaying a rescue package pledged in 2012. Failure to reach an agreement by March, when the bailout program ends, may leave the country unable to repay billions of euros in debt.

Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis met European Central Bank officials Wednesday as he presses his case with creditors, which also include the European Commission and IMF. “There is uncertainty surrounding the Greek cash position,” said Felix Herrmann, an analyst at DZ Bank AG in Frankfurt. “Greek banks, the main buyer of T-bills, are more reluctant when it comes to buying. There is a lot of uncertainty whether Greek banks will be able to get enough liquidity from March onwards and this is mirrored in T-bill prices and yields.” Greek lenders lost at least 11 billion euros in deposits in January, according to four bankers who asked not to be identified because the data were preliminary.

Withdrawals accelerated from about €4 billion in December in the run-up to elections that catapulted anti-austerity party Syriza to power. The ECB allows Greece’s banks to use as much as €3.5 billion in Greek bills as collateral in its financing operations. This is available only while the nation complies with its bailout program. Banks led gains as Greek stocks rose for a third day in Athens, climbing 2.5%. The previous sale of six-month bills on Jan. 7 drew an average yield of 2.30%. The average auction rate dropped to record-low 0.59% in October 2009 before climbing to 4.96% in June 2011, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That compares with a rate of 7.83% set at an auction in February 2000, the highest on record in data starting that month.

Read more …

“The consideration of future austerity measures should give greater weight to the unintended mental health consequences..”

• Greek Austerity Sparks Sharp Rise In Suicides (CNBC)

The harsh austerity measures imposed on the Greek public since the depths of country’s financial crisis have led to a “significant, sharp, and sustained increase” in suicides, a study published in the British Medical Journal has found. The cutbacks, launched in June 2011, saw the total number of suicides rise by over 35%—equivalent to an extra 11.2 suicides every month—and remained at that level into 2012, according to a study published this week by the University of Pennsylvania, Edinburgh University and Greek health authorities. “The introduction of austerity measures in June 2011 marked the start of a significant, sharp, and sustained increase in suicides, to reach a peak in 2012,” a statement accompanying the study said.

After Greece crashed into a six-year recession in 2008, it struggled to handle its sovereign debt burden. The country’s first round of austerity measures failed to help, and the government was forced to ask for an international bailout of some €240 billion, which came with strict conditions for further severe cutbacks and reforms. These had a crippling effect on Greece’s already stricken economy, sending unemployment levels up to 1 in 4 people. The increasing level of hardship sparked an increasing number of protests, riots and even a public suicide by a pensioner in the main square of Athens.

The University of Pennsylvania-led study also found that the suicide rate in men started rising in 2008, increasing by an extra 3.2 suicides a month. The rate then rose by an additional 5.2 suicides every month from June 2011 onward. Figures for the years after 2012 were not available, the statement added. The researchers concluded by urging governments to consider the broader implications of harsh cuts: “The consideration of future austerity measures should give greater weight to the unintended mental health consequences that may follow and the public messaging of these policies and related events.”

Read more …

“As the Greek finance minister meets Chancellor Merkel today it might help her to recall how much of Germany’s 1933-1945 external debt the country ended up paying back (close to none, which obviously helped the German economic miracle hugely)..”

• Greece, Ukraine and Russia: History Lessons (CNBC)

The two biggest geopolitical flashpoints of the year so far, and potentially of the decade, involve one of the oldest stories of all: creditors chasing their due. As Greece’s new leadership embarks on a European tour to try and negotiate compromises on its debt to the so-called troika (made up of the International Monetary Fund, European Commission and European Central Bank), and Russia threatens to call in a $3-billion bond it used to help bail out struggling Ukraine, it might be time for European leaders to take a leaf from their history books.

First World War Germany is perceived to be the most hard-line of Greece’s European creditors when it comes to renegotiations over the country’s 300-billion-euro-plus debt pile – unsurprisingly, given that Germany is both the biggest contributor to the euro zone’s part of the bailout and its own reputation for fiscal caution. Yet Germany has both suffered from large external debt and benefited from forgiveness before. The reparations it was saddled with after the First World War resulted in hyperinflation and near-economic disaster, which contributed to rising support for the Nazi Party. “As the Greek finance minister meets Chancellor Merkel today it might help her to recall how much of Germany’s 1933-1945 external debt the country ended up paying back (close to none, which obviously helped the German economic miracle hugely),” Rabobank analysts pointed out in a research note Wednesday.

Russia and Cuba Meanwhile in Russia, President Vladimir Putin said on Tuesday that Ukraine needed to repay a $3 billion loan, made while his ally Viktor Yanukovych was still Ukraine’s President, because Russia needs it to fight its own economic crisis. If Ukraine, with its economy already on the brink of disaster, is forced to repay its Russian debts earlier than the planned December 2015, it could push the country into default. Yet Russia hasn’t had a problem with debt forgiveness for neighbours and trading partners in the past. Just in July, it wrote off $32 billion of Cuba’s outstanding debt.

Read more …

“Analysts at UBS said in a recent note they expect the rig count to fall at least 31% this year, and potentially more if oil prices remain lower.”

• Here’s Why The Oil Glut May Continue (MarketWatch)

Energy companies are slashing spending budgets and shutting down oil rigs, but don’t expect U.S. oil production to slow down soon. There is so much oil available that it will take a while for those measures to make a dent in production. In addition, most of the rigs mothballed so far were in low-yield wells—low-hanging fruit that won’t make much of an impact. Analysts at UBS said in a recent note they expect the rig count to fall at least 31% this year, and potentially more if oil prices remain lower. The bulk of the decline will come in the first half of the year, with some flattening in the second half, they said in the note. A declining rig count, alongside a weaker dollar and market dynamics around short positions have driven a price spike for oil futures in recent sessions.

Futures resumed their downward trajectory on Wednesday, however, after a U.S. government agency pointed to another bump in U.S. inventories. Two other reasons that fewer rigs may not immediately translate into less production include increased drilling efficiency and an oil-well backlog that will serve as a cushion in the coming months, the Energy Information Administration has said. There has been a 16% decline in the number of active onshore drilling rigs in the continental U.S. from the end of October through late January, said the EIA. As well as shutting rigs, companies have been cutting costs to varying degrees based on balance-sheet size, with smaller companies tending to cut deeper. On average, companies have cut this year’s capital expenditures by about 30%.

Chevron last week announced a reduction in 2015 spending of 13% from 2014, taking a relatively small hatchet to its budget and focusing it mostly on its overseas exploration and production business. Chevron reduced U.S. “upstream” spending by 8%, while spending on refinery operations ticked higher. Exxon Mobil reported Monday, but as usual said it would make an announcement about capital expenditures at its analyst day scheduled for March 4. Exploration and production energy companies are going over their budgets, rationalizing spending and drilling activity “at an even faster pace than we thought possible just 6 weeks ago,” analysts at Simmons & Co. wrote in a note earlier this week. “We believe improvement in the oil supply/demand macro is on the horizon,” they said.

Read more …

An incredible story.

• Harvard’s Convicted Fraudster Who Wrecked Russia Resurfaces in Ukraine (NC)

There are about 450 think-tanks in Europe and the US currently focusing on international relations, war, peace, and economic security. Of these, about one hundred regularly analyse Russian affairs. And of these, less than ten aren’t committed antagonists of Russia. That’s barely two% of the intellectual materiel which can be counted as non-partisan or neutral in the infowar now underway between the NATO alliance and Russia. In this balance of forces, think-tanks behave like tanks – that’s the weapon, not the cistern. The Centre for Social and Economic Research (CASE) has been based in Warsaw since 1991. It claims on its website to be “an independent non-profit economic and public policy research institution founded on the idea that evidence-based policy making is vital to the economic welfare of societies.”

In its 2013 annual report, declares: “we seek to maintain a strict sense of non-partisanship in all of our research, advisory and educational activities.” Three-quarters of CASE’s annual revenues come from the European Commission; another 9% from American and other international organizations. According to CASE, that’s “an indication of progressive diversification of CASE revenue sources.” CASE Ukraine is a branch of this Polish think-tank, and at the same time a descendant, it claims, of a Harvard University-funded group which was active between 1996 and 1999. Registered since 1999 as CASE Ukraine, this calls itself “an independent Ukrainian NGO specializing in economic research, macroeconomic policy analysis and forecasting.” According to parent CASE in Warsaw, one of the group’s goals is “promoting cooperation and integration with the neighboring partners of Europe”.

This means, not only CASE Ukraine, but CASE Kyrgyzstan, CASE Moldova, CASE Georgia, and in Russia, the Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy. Independent is what CASE swears; independent isn’t what CASE represents. Investigate the names, the associations, the sources of money, the secret service engagements, and what you have is a family, a front, a cover, a closed shop, a mafia. Founders of CASE Ukraine like the American Jonathan Hay and operators of CASE Poland like the Balcerowiz family reveal a well-known anti-Russian alliance. So what are a director of the Gazprom board, Vladimir Mau; a professor of the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, Marek Dabrowski; and Simeon Djankov, Rector of the New Economic School in Moscow, and a protégé of First Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov, doing on the CASE side?

Read more …

“He kicked off his odyssey by acknowledging that ‘this country knows how to eat.'”

• One Brit Discovers Why Americans Are So Fat (MarketWatch)

America is bursting at the seams. No major development there. In fact, the U.S. makes up only 5% of the global population but tallies 13% of the world’s obese, the largest%age for any nation, according to a study from the Lancet medical journal. More than a third of our county is overweight. And we’re not getting any skinnier. As Americans, we’ve grown accustomed to, say, the gut-bomb portion sizes at the Cheesecake Factory and the bottomless pasta bowls at the Olive Garden. When Maggiano’s Little Italy serves up a massive plate of fettuccine and then hands us another whole serving on the way out, we hardly flinch. (Note the stock tickers “CAKE” and “EAT.”)

But it’s still shocking to visitors from across the pond. Shocking in a good way, at least for one British arrival who has been intoxicated enough by the options during his stay, presumably in San Francisco, that he posted some snapshots on Reddit of his recent months of gluttony. He kicked off his odyssey by acknowledging that “this country knows how to eat.” If he wanted a reaction, he got one. For whatever reason, his post struck a chord, quickly garnering more than 1.1 million views and drawing thousands of comments. Here are some of the highlights that helped make this food thread go viral this week.

Read more …

“We’re having this Groundhog Day experience, with state after state actively seeking to thwart kids from learning the truth about climate science..”

• Temperatures Rise as Climate Critics Take Aim at U.S. Classrooms (Bloomberg)

While scientists almost universally agree the world is warming, school kids in Texas, Wyoming and West Virginia will get a much less definitive answer if local activists and politicians get their way. At a time when President Obama is pushing a global effort to rein in greenhouse gases, conservative critics back home are pressing a grassroots counterattack, targeting how schools address global warming. The goal is to emphasize doubts about whether humanity is indeed baking the planet. “Climate change was only presented from one side and that side is the Al Gore position that you don’t need to discuss it, it’s a done deal,” said Roy White, a Texan retired fighter pilot. “The other side just doesn’t seem to want to allow the debate to occur.”

White doesn’t want kids indoctrinated by “misinformation,” he said, so he and 100 fellow activists have sought to change textbooks that refer to climate change as fact, rather than opinion. That the vast majority of scientists disagree with him is more a sign of dissent being quashed than of true consensus, White said. White’s band of volunteer activists, the Truth in Texas Textbooks coalition, lobbied the state to reject social studies books that they said contained factual errors or fostered an anti-American bias. Among the books’ sins: omitting mention of those who question climate science. If the coalition had its way, any reference to “global warming,” melting polar ice caps or rising sea levels would be excised from textbooks, or paired with dissenting views.

Phrases such as “consensus science” and “settled science” should be avoided, the group warned in letters to publishers last year, as they suggest a “political agenda.” So far, the campaign has had only limited results. One publisher deleted a reference to global warming and others ignored White’s appeals. The group isn’t done, however. This year, they plan to take their textbook ratings to local school districts, urging them to buy more “balanced” selections. “We want to affect the bottom line,” White said. “That means purchasing.”

To Lisa Hoyos, efforts like White’s amount to “lying about science.” Two years ago, the San Francisco mom and former union organizer co-founded the group Climate Parents to defend the teaching of climate change around the U.S. The group has members in all 50 states, Hoyos said. These days, they’re busier than ever. In Wyoming last year and South Carolina in 2012, legislators banned their states from adopting educational standards that treat human-caused global warming as settled science. A similar measure passed the Oklahoma Senate last year but failed in the State House. Michigan’s state board of education is bracing for its own debate on new standards later this year. “We’re having this Groundhog Day experience, with state after state actively seeking to thwart kids from learning the truth about climate science,” Hoyos, 49, said by telephone. “You’re seeing science standards held hostage to political machinations.”

Read more …