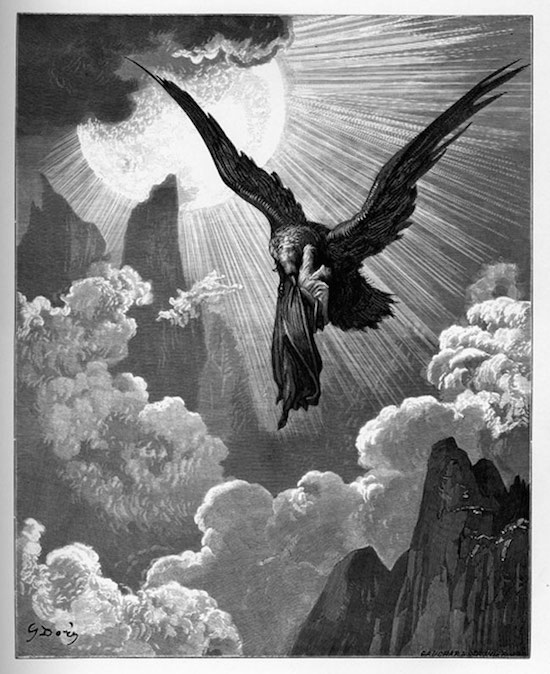

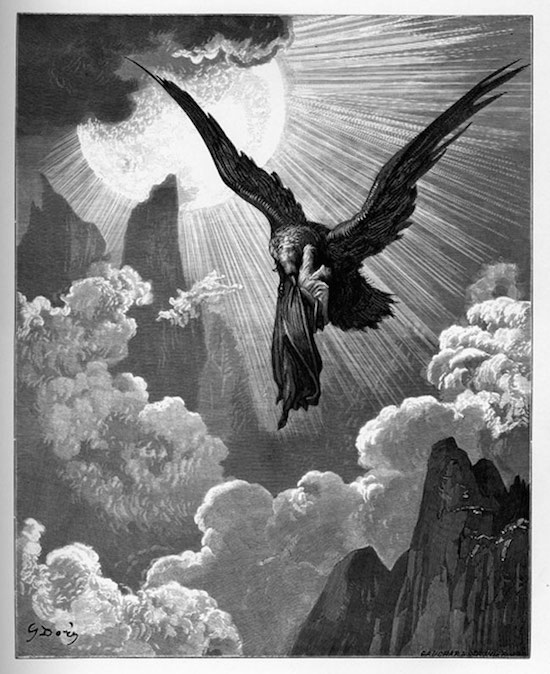

Gustave Doré Dream of the Eagle (from Dante’s Purgatory) 1868

We’ve come to the end of our little ‘chapters experiment’, using Nicole’s long article. Do let us whether you like things this way, posted in shorter parts rather than one long article. And by all means read through the whole thing one more time. It’s not going to hurt you.

This is the entire article. Part 1 is here:

Global Financial Crisis – Liquidity Crunch and Economic Depression,

Part 2 is here:

The Psychological Driver of Deflation and the Collapse of the Trust Horizon

Part 3 is here:

Declining Energy Profit Ratio and Socioeconomic Complexity

Part 4 is here:

Blind Alleys and Techno-Fantasies

and part 5 is here:

Solution Space

Intro

A great deal of intelligence is invested in ignorance when the need for illusion is deep.

Saul Bellow, 1976

More and more people (although not nearly enough) are coming to recognise that humanity cannot continue on its current trajectory, as the limits we face become ever more obvious, and their implications starker. There is a growing realisation that the future must be different, and much thought is therefore being applied to devising supposed solutions for that future.

These are generally attempts to reconcile our need to make changes with our desire to continue something very much resembling our current industrial-world lifestyle, with a view to making a seamless transition between the now and a comfortably familiar future. The presumption is that it is possible, but this rests on foundational assumptions which vary between the improbable and the outright impossible. It is a presumption grounded in a comprehensive failure to understand the nature and extent of our predicament.

We are facing limits in many ways simultaneously – not surprising since exponential growth curves for so many parameters have gone critical in recent decades, and of course even more so in recent years. Some of these limits lie in human systems, while others are ecological or geophysical. They will all interact with each other, over different timeframes, in extremely complex ways as our state of overshoot resolves itself (to our dissatisfaction, to put it mildly) over many decades, if not centuries. Some of these limits are completely non-negotiable, while others can be at least partially mutable, and it is vital that we know the difference if we are to be able to mitigate our situation at all. Otherwise we are attempting to bargain with the future without understanding our negotiating position.

The vast majority has no conception of the extent to which our modernity is an artifact of our discovery and pervasive exploitation of fossil fuels as an energy source. No species in history has had easy, long term access to a comparable energy source. This unprecedented circumstance has facilitated the creation of turbo-charged civilization.

Huge energy throughput, in line with the Maximum Power Principle, has led to tremendous complexity, far greater extractive capacity (with huge ‘environmental externalities’ as a result), far greater potential to concentrate enormous power in the hands of the few with destructive political consequences), a far higher population, far greater burden on global carrying capacity, and the ability to borrow from the future to satisfy the insatiable greed of the present. The fact that we are now approaching so many limits has very significant implications for our ability to continue with any of these aspects of modern life. Therefore, any expectation that a future in the era of limits is likely to resemble the present (with a green gloss) are ill-founded and highly implausible.

The majority of the Big Ideas with which we propose to bargain with our future of limits to growth rests on the notion that we can retain our modern comforts and conveniences, but that somehow we will do so with far less resource use, and with a fraction of the energy we currently employ. The most mainstream discussions revolve around ‘green growth’, where it is suggested that eternal economic growth can occur on a finite planet, and that we will magically decouple of that growth from the physical basis upon which it rests. Proponents argue that we have already accomplished this to an extent, as the apparent energy intensity of developed state economies has fallen.

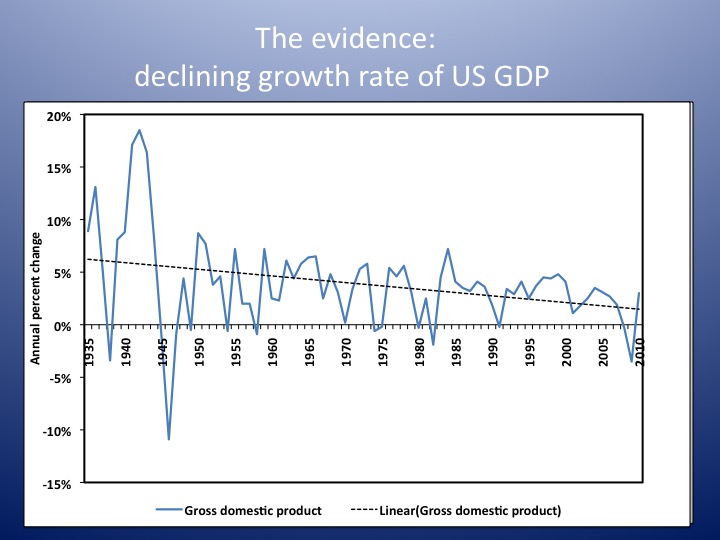

In actuality, all that has happened is that the energy deployed to provide developed world comforts has been used in the emerging markets where goods destined for our markets are manufactured, so that the consumption falls within someone else’s energy budget. In reality there has been no decoupling at all. Economic growth requires energy, and there is an exceptionally high correlation between the two. Even the phantom growth of the bubble era, based on the expansion of virtual wealth, requires energy in order to maintain the complexity of the system that generates it.

It is crucial that we understand the boundaries of solution space, in order to be able to focus our finite resources (in every sense of the word) on that which is inherently workable, at least in theory. ‘Workable In theory’ implies that, while there is no guarantee of success given a large number of unpredictable factors, there is also no obvious prima facie barrier to success. If, however, we throw our resources at ideas that are subject to such barriers, and therefore lie beyond solution space, we guarantee that those initiatives will fail and that the resources so committed will have been wasted. It is important to note that ‘success’ does not mean being able to maintain anything remotely resembling business as usual. It refers to being able to achieve the best possible outcome under the circumstances.

Sculptors work by carving away excess material in order to reveal the figure within the block they are working with. Similarly, we can carve away from the featureless monolith of conceivable approaches those that we can see in advance are doomed to fail, leaving us with a figuratively coherent group of potentially workable ideas.

In order to carve away the waste material and get closer to a much smaller set of viable possibilities, we need to understand some of the non-negotiable factors we will be facing, each of which has implications restrictive of viable solution space. Many of these issues are the fundamental substance of the message we have been propagating at the Automatic Earth since its inception and will therefore constitute a review for our regular readership. For more detail on these topics, check out our primers section.

Global Financial Crisis – Liquidity Crunch and Economic Depression

As we have maintained since the Automatic Earth’s launch in early 2008, we have lived through a gigantic monetary expansion over the last 30 years or so – the largest financial departure from reality in human history. In doing so we have created a crisis of under-collateralization. This period was highly inflationary, as we saw a vast increase in the supply of money and credit versus available goods and services. Both currency printing and credit hyper-expansion constitute inflation, but the outcome, and therefore prescription, for each is very different. While currency printing cuts the real wealth pie into many more pieces, each of which will be very small, credit expansions such as this one create multiple and mutually exclusive claims to the same pieces of pie, hence we have generated a vast quantity of excess claims to underlying real wealth.

In other words, we have created a bubble of virtual wealth, with no substance to back up the pile of promises to repay that it rests upon. As we have said before, this amounts to playing a giant game of musical chairs where there is perhaps one chair for every hundred people playing the game. When the music stops, those best positioned to understand the rules of the game will grab a chair as quickly as possible. Everyone else will be out of the game. The endgame of credit expansion is always a credit implosion, where the excess claims are rapidly and messily extinguished. This is, of course, deflation by definition – a contraction in the supply of money and credit relative to available goods and services – through the collapse of the credit supply, where credit is of the order of 99% of the effective money supply.

A credit implosion crashes both the money supply and the velocity of money – the rate at which money circulates in the economy. Together these factors determine how much economic activity can be sustained. With both the money supply and the velocity of money very low, a state of liquidity crunch exists, where there is insufficient liquidity in the economy to connect buyers and sellers, or producers and consumers. Nothing moves, so there is little or no economic activity. Note that demand is not what one wants, but what one can pay for, so with little purchasing power available, demand will be very low under such circumstances.

During the expansion, both the money supply and the velocity of money increased dramatically, and the resulting artificial stimulation of demand led to an increase in supply, with the ability to sustain a much larger than normal amount of economic activity. But once the limit is reached, where all the income streams of the productive economy can no longer service the debt created, and there are no more willing borrowers or lenders, the demand stimulation disappears, leaving a great deal of supply without a market. The demand that had been effectively borrowed from the future, must be ‘repaid’ once the bubble bursts, leading to a prolonged period of low demand. The supply that had arisen to service it no longer has a reason to exist and cannot be maintained.

The economy moves into a period of seizure under such cIrcumstances. We have frequently compared attempting to run an economy with too small a money supply in circulation to trying to run an automobile with the oil warning light on, indicating too little lubricant. Engines seize up when run with too little lubricant, a role played by money in the case of the engine of the economy. The situation created can also be compared to a computer operating system crash, where nothing functions until the system has been rebooted. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, people noted that they had plenty of everything except money. Liquidity crunch creates a condition of artificial scarcity, where even being surrounded by resources is of little use for a period of time once the operating system has crashed and has yet to be ‘rebooted’.

We will be looking at a period of acute liquidity crunch followed by a long period of chronic financial instability. The initial contraction will be driven by fear and that fear will persist for a long time. This will result in little credit being made available, and only at high cost. In other words, interest rates, which are a risk premium, will be very high as we move beyond the initial phase of contraction and fear is in the drivers seat. Deflation and economic depression are mutually reinforcing, hence once that downward spiral, or vicious circle, dynamic has taken hold, we will remain in its grip for many years.

Given that the cost of capital will be very high, and there will be little purchasing power, proposed solutions which are capital-intensive will lie outside solution space.

The Psychological Driver of Deflation and the Collapse of the Trust Horizon

The collective mood shifts rapidly from optimism and greed to pessimism and fear as the bubble bursts, and as it does so, the financial system moves from expansion to contraction. Financial contraction involves the breaking of promises right left and centre, with credit instruments drastically revalued downwards in the process. As the promises that back them cease to be credible, value disappears extremely rapidly. This is deflation and the elimination of excess claims to underlying real wealth.

Instruments once regarded as money equivalents will lose that status through the loss of confidence in them, causing the supply of what retains sufficient confidence to still be regarded as money to collapse. The more instruments lose the confidence that confers value upon them, the smaller the effective money supply will be, and the more confidence will become a rare ‘commodity’. Being grounded in psychology is the primary reason that deflation cannot be overcome through policy adaptations which are inherently too little and too late. Nothing moves as quickly as a collective loss of confidence in human promises, and nothing destroys value as comprehensively.

The same abrupt change in collective mood will also drive contraction in the real economy, but more slowly, since the time constant for change in the real world is much slower than in the virtual world of finance. This process will also result in broken promises as structural dependencies fracture when there is no longer enough to go around. There will be wage and benefit cuts, layoffs, strikes, strike-breaking, breaches of contract, business failures and more on a huge scale, and these will fuel further fear, anger and the destruction of trust.

In the political realm, trust, such as it is, will be an early casualty. Political promises have been regarded as highly suspect for a long time in any case, but considering that the electorate tends consistently to vote for whomever tells them the largest number of comforting lies, this is not particularly surprising. Our political system selects for mendaciousness by design, since no party is normally elected by telling the truth, yet we have still collectively retained some faith in the concept of democracy until relatively recently. In recent years, however, it has become increasingly clear that the political institutions in supposedly democratic nations have largely been bought by big capital. More often than not, and more blatantly than ever, the political machinery has come to serve those special interests, not the public interest.

The public is increasingly realizing that ‘representative democracy’ leaves them unrepresented, as they see more and more examples of austerity for the masses combined with enormous bailouts guaranteeing that the large scale gamblers of casino capitalism will not take losses on the reckless bets they made gambling with other people’s money. In the countries subjected to austerity, where the contrast is the most stark, a wave of public anger is already depriving national governments, or supranational governance institutions where applicable (ie Europe), of political legitimacy. As more and more states slide into the austerity trap as a result of their unsustainable debt burdens, this polarization process will continue, driving wedges between the governors and the governed which will make governance far more difficult.

Governments struggling with the loss of political legitimacy are going to find that people will no longer follow rules once they feel that the social contract has been violated, and that rules no longer represent the public interest. When the governed broadly accept that society functions under the rule of law, in other words that all are equally subject to the same rules, then they tend to internalize those rules and follow them without the need for negative incentives or outright enforcement. However, once the dominant perception becomes that rules are imposed only on the powerless, to their detriment and for the benefit of the powerful, while the well connected can do as they please, then general compliance can cease very quickly.

Without compliance, force would become necessary, and we are indeed likely to see this occur as a transitional phase as social polarization increases in a climate of increasing anger. The transitional element arises from the fact that force, especially as exercised technologically at large scale, requires substantial resources which are unlikely to remain available. Force produces reaction, straining the fabric of society, quite possibly to breaking point.

As contagion propagates the impact of financial and economic contraction, we will rapidly be moving from a long era of high trust in the value of promises to one of low trust. The trust horizon will contract sharply, leaving supranational and national governments lying beyond its reach, as stranded assets from a trust perspective. Trust determines effective organizational scale, so when the trust horizon draws in, withdrawing political legitimacy in its wake, larger scale entities, whether public or private, are going to find it extremely difficult to function. Effective organizational scale had been increasing for the duration of our long economic expansion, forcing an across the board scaling up of all manner of organizations by increasing the competitiveness accruing to large scale. As we scaled up, we formed structural dependencies on these larger scale entities’ ability to function.

While the scaling-up process was reasonable smooth and seamless, the scaling-down process will not be, as the lower rungs of the figurative ladder we climbed to reach this pinnacle have been kicked out as we ascended. Structural dependencies are going to fail very painfully as large scale ceases to be effective and competitive, leading to abrupt dislocations with ricocheting impacts.

Proposed solutions to our predicament that depend on the functioning of large-scale organizations operating in a top-down manner do not lie within viable solution space.

Instability and the ‘Discount Rate’

The pessimism-and-fear-driven psychology of contraction differs dramatically from the optimism-and-greed-driven psychology of expansion. The extreme complacency as to systemic risk of recent years will be replaced by an equally extreme risk aversion, as we move from overshoot in one direction to undershoot in the other. The perception of economic visibility is gong to change substantially, as we move from a period where people thought they knew where things were headed into an era where fear and confusion reign, and the sense of predictability evaporates abruptly.

This is an important psychological shift, as it affects an aspect known as the ‘discount rate’, which reflects the extent to which we think in the short term rather than the long term, or the extent to which we value the present over the future. The perceived rate of change is an important factor in determining the discount rate, and fear, being a very sharp emotion, causes the rate of change to accelerate markedly, driving the discount rate sharply higher in contractionary times.

True long term thinking is relatively rare. We manage an approximation of it at times when all immediate needs, along with many mere ‘wants’, are met and we are not concerned about this condition changing, in other words at times when we take a comfortable situation for granted. At such times, the longer term view is a luxury we can afford, and we find it relatively simple to summon the presence of mind to think abstractly and constructively, and to ponder circumstances which are are neither personal nor immediate. Even at such times, however, it is not particularly common for humans to transcend mere contemplation and actually act in the interests of the long term, especially if it involves aspects beyond the personal, or perhaps familial.

As the financial bubble bursts, and we rapidly begin to pick up on the fear of others and feel the consequences of contagion in our own lives, our collective discount rates are going to sky-rocket. In a relatively short period of time, a large percentage of the population is going to begin worry about immediate needs, let alone wants, not being met. A short time later those worries are likely to transition into reality, as has already happened in the countries, like Greece, in the forefront of the bursting bubble. As discount rates go through the roof, the luxury of the longer term view, which is always quite ephemeral, is likely to disappear altogether.

Where people have no supply cushions and find themselves abruptly penniless, cold, thirsty, hungry or homeless, the likelihood of them considering anything much beyond the needs of the day at hand is very low. Under such circumstances, the present becomes the only reality that matters, and societies are abruptly pitched into a panicked state of short term crisis management. This of course underlines the need to develop supply cushions and contingency plans in advance of a bubble bursting, so that a greater percentage of people might be able to retain a clear head and the ability to plan more than one day at a time. Unfortunately, few are likely to heed advance warnings and we can expect society to shift rapidly into a state of short-termism.

Given the coming rise in collective discount rates, if proposed solutions depend on the ability for societies to engage in rational planning for longer term goals, then those solutions are not part of solution space.

The Psychology of Contraction and Social Context

Expansionary times are times of relative peace and prosperity. If those conditions persist for a relatively long time, trust builds slowly and societies become more inclusive and cooperative, tending to perceive common humanity and focus on similarities rather than differences. In such times we reach out and interact with distant people, even if we have no relationship of personal trust with them, as we have, over time, vested our trust in stable institutional frameworks for managing our affairs. This institutional trust replaces the need for trust at a personal level and is a key factor in our ability to scale up our economies and their governance structures. Individuals raised in such an environment tend to show a presumption of trust towards others, and their inclination is generally to act cooperatively.

There is a sharp contrast between this stable state of affairs and the circumstances which pertain when suddenly the pie is shrinking and there is not enough to go around. As difficult as it can be to share gains in a way perceived to be fair, it is infinitely more difficult to share losses in a way that is not extremely divisive. As elucidated above, a deflationary credit implosion involved the wholesale destruction of excess claims to underlying real wealth, meaning that a majority of people who thought they had a valid claim to something of tangible value are going to find that they do not. The losses will be very widespread, but uneven, and the perception of unfairness will be almost universal.

Under such circumstances a sense of common humanity is much less prevalent, and the focus shifts from similarities to the differences upon which social divisions are founded and then inflamed. An ‘us versus them’ dynamic is prone to take hold, where ‘us’ becomes ever more tightly defined and ‘them’ becomes an ever more pejorative term. People build literal and figurative walls and peer suspiciously at each other over them. Rather than working together in the attempt to address concerns common to all, division shifts the focus from cooperation to competition. A collectively constructive mindset can easily morph into something far more motivated by negative emotions such as jealousy and revenge and therefore far more destructive of perceived commonality.

The kind of initiatives which capture the public imagination in expansionary times are not at all the type which get traction once a contractionary dynamic takes hold. Attempts to build cooperative projects are going to be facing a rising tide of negative social mood, and will struggle to get off the ground. Sadly, negative ideas are far more likely to go viral than positive ones. Novel movements grounded in anger and fear may arise to feed on this new emotional context and thereby be empowered to wreak havoc on the fabric of society, notably through providing a political mandate to extremists with an agenda of focusing blame on to some identifiable, and marginalizable, social group.

While it will not be the case that cooperative endeavours will be impossible to achieve, they will require additional effort, and are likely to succeed only at a much smaller scale in a newly fractured society than might previously have been expected. It is very much a worthwhile effort, and will be far simpler if begun prior to the end of the period of cooperative presumption. All the more reason to adapt to a major trend change adapt in advance. There is nothing so dangerous as collectively dashed expectations.

If proposed solutions depend on a cooperative social context at large scale, they will not be part of solution space.

Energy – Demand Collapse Followed by Supply Collapse

As we have noted many times, energy is the master resource, and has been the primary driver of an expansion dating back to the beginning of the industrial revolution. In fossil fuels humanity discovered the ‘holy grail’ of energy sources – highly concentrated, reasonably easy to obtain, transportable and processable into many useful forms. Without this discovery, it is unlikely that any human empire would have exceeded the scale and technological sophistication of Rome at its height, but with it we incrementally developed the capacity to reach for the stars along an exponential growth curve.

We increased production year after year, developed uses for our energy surplus, and then embedded layer upon successive layer of structural dependency on those uses within our societies. We were living in an era of a most unusual circumstance – energy surplus on an unprecedented scale. We have come to think this is normal as it has been our experience for our whole lives, and we therefore take it for granted, but it is a profoundly anomalous and temporary state of affairs.

We have arguably reached peak production, despite a great deal of propaganda to the contrary. We still rely on the giant oil fields discovered decades ago for the majority of the oil we use today, but these fields are reaching the end of their lives and new discoveries are very small in comparison. We are producing from previous finds on a grand scale, but failing to replace them, not through lack of effort, but from a fundamental lack of availability. Our dependence on oil in particular is tremendous, given that it underpins both the structure and function of industrial society in a myriad different ways.

An inability to grow production, or even maintain it at current levels past peak, means that our oil supply will be constricted, and with it both the scope of society’s functions and our ability to maintain what we have built. Production from the remaining giant fields could collapse, either as they finally water out or as production is hit by ‘above ground factors’, meaning that it could be impacted by rapidly developing human events having nothing to do with the underlying geology. Above ground factors make for unpredictable wildcards.

Financial crisis, for instance, will be profoundly destabilizing, and is going to precipitate very significant, and very negative, social consequences that are likely to impact on the functioning of the energy industry. A liquidity crunch will cause purchasing power to collapse, greatly reducing demand at personal, industrial and national scales. With production geared to previous levels of demand, it will feel like a supply glut, meaning that prices will plummet.

This has already begun, as we have recently described. The effect is exacerbated by the (false) propaganda over recent years regarding unconventional supplies from fracking and horizontal drilling that are supposedly going to result in limitless supply. As far as price goes, it is not reality by which it is determined, but perception, even if that perception is completely unfounded.

The combination of perception that oil is plentiful, falling actual demand on economic contraction, and an acute liquidity crunch is a recipe for very low prices, at least temporarily. Low prices, as we are already seeing, suck the investment out of the sector because the business case evaporates in the short term, economic visibility disappears for what are inherently long term projects, and risk aversion becomes acute in a climate of fear.

Exploration will cease, and production projects will be mothballed or cancelled. It is unlikely that critical infrastructure will be maintained when no revenue is being generated and money is very scarce, meaning that reviving mothballed projects down the line may be either impossible, or at least economically non-viable.

The initial demand collapse may buy us time in terms of global oil depletion, but at the expense of aggravating the situation considerably in the longer term. The lack of investment over many years will see potential supply collapse as well, so that the projects we may have thought would cushion the downslope of Hubbert’s curve are unlikely to materialize, even if demand eventually begins to recover.

In addition, various factions of humanity are very likely to come to blows over the remaining sources, which, after all, confer upon the owner liquid hegemonic power. We are already seeing a new three-way Cold War shaping up between the US, Russia and China, with nasty proxy wars being fought in the imperial periphery where reserves or strategic transport routes are located. Resource wars will probably do more than anything else to destroy with infrastructure and supplies that might otherwise have fuelled the future.

Given that the energy supply will be falling, and that there will, over time, be competition for increasingly scarce energy resources that we can no longer take for granted, proposed solutions which are energy-intensive will lie outside of solution space.

Declining Energy Profit Ratio and Socioeconomic Complexity

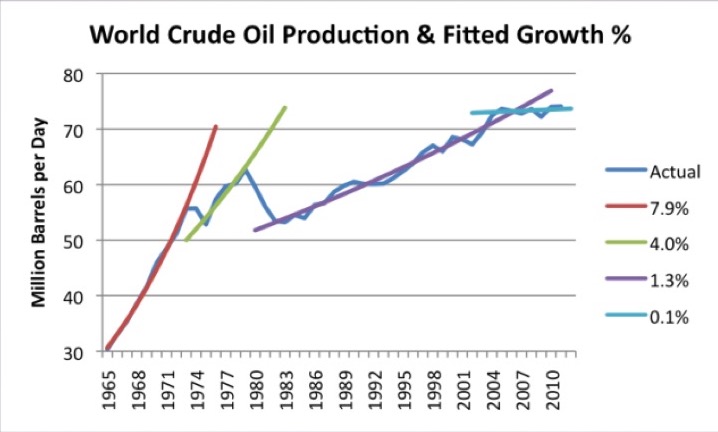

It is not simply the case that energy production will be falling past the peak. That is only half the story as to why energy available to society will be drastically less in the future in comparison with the present. The energy surplus delivered to society by any energy source critically depends on the energy profit ratio of production, or energy returned on energy invested (EROEI).

The energy profit ratio is the comparison between the energy deployed in order to produce energy from any given source, and the resulting energy output. Naturally, if it were not possible to produce more than than the energy required upfront to do so (an EROEI equal to one), the exercise would be pointless, and ideally one would want to produce a multiple of the input energy, and the higher the better.

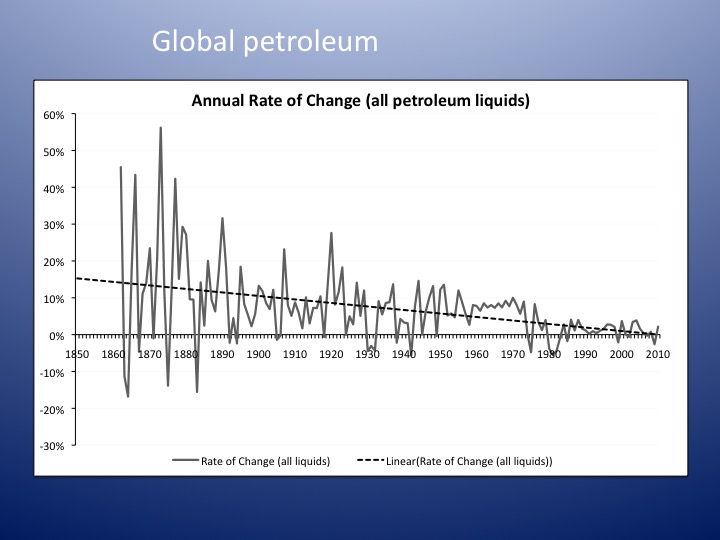

In the early years of the oil fuel era, one could expect a hundred-fold return on energy invested, but that ratio has fallen by something approximating a factor of ten in the intervening years. If the energy profit ratio falls by a factor of ten, gross production must rise by a factor ten just for the energy available to society to remain the same. During the oil century, that, and more, is precisely what happened. Gross production sky-rocketed and with it the energy surplus available to society.

However, we have now produced and consumed the lions’s share of the high energy profit ratio energy sources, and are depending on lower and lower EROEI sources for the foreseeable future. The energy profit ratio is set to fall by a further factor of ten, but this time, being past the global peak of production, we will not be able to raise gross production. In fact both gross production and the energy profit ratio will be falling at the same time, meaning that the energy surplus available to society is going to be very sharply curtailed. This will compound the energy crisis we unwittingly face going forward.

The only rationale for supposedly ‘producing energy’ from an ‘energy source’ with an energy profit ratio near, or even below, one, would be if one can nevertheless make money at it temporarily, despite not producing an energy return at all. This is more often the case at the moment than one might suppose. In our era of money created from nothing being thrown at all manner of losing propositions, as it always is at the peak of a financial bubble, a great deal of that virtual wealth has been pursuing energy sources and energy technologies.

Prior to the topping of the financial bubble, commodities of all kinds had been showing exponential price rises on fear of impending scarcity, thanks to the human propensity to extrapolate current trends, in this case commodity demand, forward to infinity. In addition technology investments of all kinds were highly fashionable, and able to attract investment without the inconvenient need to answer difficult questions. The combination of energy and technology was apparently irresistible, inspiring investors to dream of outsized profits for years to come. This was a very clear example of on-going dynamics in finance and energy intertwining and acting as mutually reinforcing drivers.

Both unconventional fossil fuels and renewable energy technologies became focii for huge amounts of inward investment. These are both relatively low energy profit energy sources, on average, although the EROEI varies considerably. Unconventional fossil fuels are a very poor prospect, often with an EROEI of less than one due to the technological complexity, drilling guesswork and very rapid well depletion rates.

However, the propagandistic hype that surrounded them for a number of years, until reality began to dawn, was sufficient to allow them to generate large quantities of money for those who ran the companies involved. Ironically, much of this, at least in the United states where most of the hype was centred, came from flipping land leases rather than from actual energy production, meaning that much of this industry was essentially nothing more than an elaborate real estate ponzi scheme.

Renewables, as we currently envisage them, unfortunately suffer from a relatively low energy profit ratio (on average), a dependence on fossil fuels for both their construction and distribution infrastructure, and a dependence on a wide array of non-renewable components.

We typically insist on deploying them in the most large-scale, technologically complex manner possible, thereby minimising the EROEI, and quite likely knocking it below one in a number of cases. This maximises monetary profits for large companies, thanks to both investor gullibility and greed and also to generous government subsidy regimes, but generally renders the exercise somewhere between pointless and counter-productive in long term energy supply terms.

For every given society, there will be a minimum energy profit ratio required to support it in its current form, that minimum being dependent on the scale and complexity involved. Traditional agrarian societies were based on an energy profit ratio of about 5, derived from their food production methods, with additional energy from firewood at a variable energy profit ratio depending on the environment. Modern society, with its much larger scale and vastly greater complexity, naturally has a far higher energy profit ratio requirement, probably not much lower than that at which we currently operate.

We are moving into a lower energy profit ratio era, but lower EROEI energy sources will not be able to maintain our current level of socioeconomic complexity, hence our society will be forced to simplify. However, a simpler society will not be able to engage in the complex activities necessary to produce energy from these low EROEI sources. In other words, low energy profit ratio energy sources cannot sustain a level of complexity necessary to produce them. They will not fuel the simpler future which awaits us.

Proposed solutions dependent on the current level of socioeconomic complexity do not lie within solution space.

Blind Alleys and Techno-Fantasies

The majority of proposals made by those who acknowledge limits fail on at least one of the previous criteria, and often several, if not all of them. Solution space is smaller than we typically think. The most common approach is to insist on government policies intended to implement meaningful change by fiat. Even in the best of times, government policy is a blunt instrument which all too often achieves the opposite of its stated intention, and in contractionary times the likelihood of this increases enormously.

Governments are reactive – and slowly – not proactive. Policies typically reflect the realities of the past, not the future, and are therefore particularly maladaptive at times of large scale trend change, particularly when that change unfolds rapidly. Those focusing on government policy are mostly not thinking in terms of crisis, however, but of seamless proactive adjustment – the kind of which humanity is congenitally incapable.

There is a common perception that government policy and its effect on society depends critically on who holds the seat of power and what policies they impose. The assumption is that elected leaders do, in fact, wield the power to determine and implement their chosen policies, but this has become less and less the case over time. Elected leaders are the public face of a system which they do not control, and increasingly act merely as salesmen for policies determined behind the scenes, mostly at the behest of special interest groups with privileged political access.

It actually matters little who is the figure-head at any given time, as their actions are constrained by the system in which they are embedded. Even if leaders fully understood the situation we face, which is highly unlikely given the nature of the leadership selection process, they would be unable to change the direction of a system so much larger than themselves.

Where public pressure on elected governments develops around a specific issue, for whatever reason, the political response is generally to act in such a way as to appear to do something meaningful, while actually making no substantive change at all. Often the appearance of action is nothing more than vacuous political spin, assuaging public opinion while doing nothing to threaten the extractive interests driving the system in the same direction as always. We cannot expect truly adaptive initiatives to emerge from a system hostage to powerful vested interests and therefore locked into a given direction.

Public understanding of the issues agitated for or against tends, unfortunately, to be limited and one-dimensional, meaning that it is essentially impossible to create public pressure for truly informed policy changes, and it is relatively simple to claim that the appearance of action constitutes actual action. A short public attention span makes this even simpler. People are also extremely unlikely to vote for policies which, if they were to make a meaningful difference, would amount to depriving those same people of the outsized consumption habits to which they have become accustomed. The insurmountable obstacles to achieving change through government policy become obvious.

Planned degrowth assumes the possibility of a smooth progression towards a lower consumption future, but this is not how contractions unfold following the bursting of a bubble. What we can expect is a series of abrupt dislocations that are going to wreak havoc with our collective ability to plan anything at all for many years, by which time we will already be living in a lower consumption future arrived at chaotically. Effective planning for an epochal shift requires the capacity for top-down policy implementation at large scale, combined with social cohesion, the ability to maintain complexity, and the energy to maintain control over a myriad distinct aspects simultaneously. It is simply not going to happen in the manner that proponents envisage.

Similarly, a steady state economy is not a realistic construct in light of many non-negotiable realities. Human history, and in fact the non-human evolution which preceded it, is a dynamic history of boom and bust, of niches opening up, being exploited, being over-exploited and collapsing. It is a history of opportunism and the consequences following from it. In the human experience, boom and bust in the form of the rise and fall of empire is an emergent property of civilizational scale. A steady state at this scale is prima facie impossible.

An approximation of steady state can exist under certain circumstances, where a population well below ecological carrying capacity, and surrounded by abundance, is left in isolation for a very long period of time. The Australian aboriginal existence prior to the European invasion is probably the best example, having persisted for tens of thousands of years. The circumstances which permitted it were, however, diametrically opposite to those we currently face.

Proponents of the steady state economy do not seem to appreciate the extent to which we have long since transgressed the point of no return from the perspective of being able to maintain what we have built. Even if we were merely approaching limits, instead of having moved substantially into overshoot, we would not be able to hold society in stasis just below those limitations.

Populations grow and expansion proceeds with it. Intentionally preventing population growth globally is unrealistic. Even China, as a single country, has struggled with population control policies, and has had to take drastic and dictatorial measures in order to slow population growth. This clearly relies on strong top-down control, which is only barely possible at a national level and will never be possible at a global level.

In China we are also going to see that the outcome of population control has challenging consequences, and that a policy supposedly designed to foster stability can have the opposite effect. The desire for a male child has dangerously distorted the gender ratio in ways which will leave the country with a large excess of young men with no prospects for either work or marriage. That is a guarantee of trouble, either at home or abroad, or possibly both. There will also be far too few employed young people to look after a burgeoning elderly population, meaning a rapid die-off of the elderly cohort at some point.

Even then China is unlikely to have managed to get itself back below the carrying capacity it has done so much to destroy during its frantic dash for growth. The tremendous modernity drive China has engaged in essentially undone any benefit curbing population growth might have had, by increasing energy and resource consumption per capita by an enormous margin. It is population times consumption which determines impact, and in China the ecological impact has in many ways been catastrophic. That has to some extent been compensated for by obtaining access to a great deal of land in other countries, but economic colonialism has done nothing for global stability.

While it is possible to conceive, as some steady-state and degrowth proponents do, of a world in which civilization and large-scale urbanism have been dismantled in favour of autonomous, yet networked, village-scale settlements, that does not make it even remotely realistic. Humanity may, in the distant future, after the overshoot condition has been resolved by nature, as it will eventually be, find itself living in villages once again, but they would not be networked in the modern, technological sense, and the population they housed would be very smaller smaller than at present.

If it is below carrying capacity, then it will grow again, restarting the cycle of expansion and contraction rather than settling for a steady-state. Reaching for the stars again would not be possible however, as the necessary energy and resources have already been consumed or dissipated.

People are often inclined to think that a different trajectory is a matter of choice – for instance that we must collectively choose to live differently in order to prevent an ecological catastrophe. In fact it is not a matter of choice at all. There is no basis for top-down control capable of delivering meaningful change, nor would humanity ever collectively choose to scale back its consumption pattern, although individuals can and do. Given opportunities as a species, we take them, as evolution has shaped us to do.

Groups which made a habit of forgoing opportunities in the past would quickly have been out-competed by those who did not. We are the descendants of a long long line of opportunists, selected over millennia for our flexibility in turning an incredibly wide range of circumstances to our advantage. But, in this instance we will have no choice – the shift to lower consumption will be imposed on us by circumstance. The element of choice will be only in how we choose to face that which we cannot change.

Another class of ideas for ways forward is grounded in techno-optimism, suggesting that because human beings are clever and creative, and have tended to push back apparent limits before, that we will be able to do so indefinitely. The notion is that changing our trajectory is unnecessary because limits can always be circumvented. Needless to say, such a view is not grounded in physical reality. These ‘solutions’ are entrepreneurial rather than policy-driven, although they may expect to be facilitated through policy.

Ideas in this category would include such things as smart renewables-based power grids, high-performance electric cars, high-tech energy storage systems, thorium reactors, fusion reactors, biofuels, genetically modified (pseudo)foodstuffs, geoengineering, enhanced automation, high-tech carbon sequestration, global carbon trading platforms, electronic crypto-currencies, clean-tech, vertical farming skyscrapers and many other notions.

Notice that all of these presume the ready availability of cheap energy and resources, along with large quantities of capital, and all assume that technological complexity can be maintained or even increased. Options such as these also have a substantial dependence on the continuation of globalized trade in both goods and services in order to satisfy their complex supply chains. However, globalization depends on the ability to operate at large scale in extremely complex ways, it depends on cheap energy, it depends on maintaining trust in trading partners, and it depends on the ability to travel without facing unacceptable levels of physical risk from piracy or conflict.

Trade does very poorly in times of financial and economic contraction. In the Great Depression of the 1930s, trade fell by 66% in two years. Trust collapses, and with it the contractual ability to agree on risk-sharing arrangements. Letters of credit become impossible to obtain in a credit crunch, and without them goods do not move.

Many goods will in any case have no market, as there will be little purchasing power for anything but essentials, and possibly not even sufficient for those. As we move from the peak of globalized trade, there will be an enormous excess of transport capacity, which will drive prices down relentlessly to the point where transporting goods becomes uneconomic. Much transport capacity will be scrapped. Without credit to oil the wheels of trade, our highly leveraged economic system will grind to a halt.

It is natural that we regard our current situation as being normal, and take for granted that the march of technological progress – the only reality most of us have known – will continue. Few question very deeply the foundations of our societies, and even those who do recognize that change must occur rarely realize the extent to which that change will inevitably strike at the fundamental basis of modern existence. Globalization has peaked and will shortly be moving into reverse. The world will be a very different place as a result.

Solution Space

To use the word ‘solution’ is perhaps misleading, since it could be said to imply that circumstances exist which could allow us to continue business as usual, and this is not, in fact, the case. A crunch period cannot be avoided. We face an intractable predicament, and the consequences of overshoot are going to manifest no matter what we do. However, while we may not be able to prevent this from occurring, we can mitigate the impact and lay the foundation for a fundamentally different and more workable way of being in the world.

Acknowledging the non-negotiable allows us to avoid beating our heads against a brick wall, freeing us to focus on that which we can either influence or change, and acknowledging the limits within which we must operate, even in these areas, allows us to act far more effectively without wasting scarce resources on fantasies. There are plenty of actions which can be taken, but those with potential for building a viable future will be inexpensive, small-scale, simple, low-energy, community-based initiatives. It will be important to work with natural systems in accordance with permaculture principles, rather than in opposition to them as currently do so comprehensively.

We require viable ways forward across different timeframes, first to navigate the rapid-onset acute crisis which the bursting of a financial bubble will pitch us into, and then to reboot our global operating system into a form less reminiscent of a planet-killing ponzi scheme. The various limits we face do not manifest all at the same time, and so to some extent can be navigated sequentially. The first phase of our constrained future, which will be primarily financial and social, will occur before the onset of energy supply difficulties for instance. Some initiatives are of particular value at specific times, and other have general value across timescales.

Moving into financial contraction is going to feel like having the rug pulled out from under our feet, and all the assumptions upon which we have based our lives invalidated all at once. Preparing in advance can make all the difference to the impact of such an event. At an individual level, it is important to avoid holding debt and to hold cash on hand. It is also very useful to have prepared in advance by developing practical skills, obtaining control over the essentials of one’s own existence where possible and being located in an auspicious place. Human skills such as mediation and organizational ability will be very useful for calming inevitable social tensions.

However, community initiatives will have far greater impact than individual actions. The most effective paths will be those we choose to walk with others, as even in times when effective organizational scale is falling, it does not fall far enough to make acting individually the most adaptive strategy. Even in contractionary times, cooperation is not only possible, but vital. In the absence of lost institutional trust, it must occur within networks of genuine interpersonal trust, and these are of necessity small. Building such networks in advance of crisis is exceptionally important, as they are very much more difficult to construct after the fact, when we will be facing an unforgiving social atmosphere.

Cohesive communities will act together in times of crisis, and will be able to offer significant support to each other. The path dependency aspect is important – the state we find ourselves in when crisis hits will be an major determinant of how it plays out in a given area. Anything people come together to do will build social capital and relationships of trust, which are the foundation of society. Community gardens, perma-blitzes (permaculture garden make-overs), maker-spaces, time-banks, savings pools, local currency initiatives, community hub developments, skills training programmes, asset mapping and contingency planning are but a few of the possibilities for bringing people together.

Essential functions can be reclaimed locally, providing for far greater local self-sufficiency potential. The existence of locally-focused businesses, with local supply chains and local distribution networks for supplying essential goods and services will be a major advantage, hence establishing these in advance will be highly adaptive. Choosing to form them as cooperatives is likely to increase their resilience to external shocks as risks are shared. Where they can function at least partially through alternative trading arrangements, or as part of a local currency network, they can be even more beneficial.

Alternative trading arrangements are a particularly important component of local self-sufficiency during times of financial crisis, as they are able to mitigate the acute state of liquidity crunch which will be creating artificial scarcity. Implementing alternative means of trading will allow a much larger proportion of economic activity to survive, and this will allow many more people to be able to provide for themselves and their families. This in turn creates much greater social stability. Alternative currencies in particular are already being relied on in the countries at the forefront of financial crisis, which already find themselves facing liquidity shortage.

It is by no means necessary to wait until crisis hits before establishing such systems. Indeed they can have considerable value locally even in stable times. Since they only constitute money in one area, and, being fiat currencies, must necessarily operate within the trust horizon, they help to retain purchasing power locally, rather than allowing it to drain away continually. Once well established, alternative currencies can go from being parallel systems to being the major form of liquidity available locally.

Beyond a close-knit community, it will be very helpful to have an informed layer of local government, as this confers the potential for a top-down/bottom-up partnership between local government and the grass roots. Local government is capable of removing barriers to people looking after themselves, assisting with the propagation of successful grass roots initiatives and acting facilitate adaptive responses with the resources at its disposal, even though these will be for more limited than currently.

Contingency planning in advance for the distribution of scarce local resources would be wise. With the trust horizons drawing inwards, local government may be the largest scale of governance still lying within it, and therefore still effective. It operates at a far more human scale than larger political structures, and is far more likely to have the potential for transparency, accountability and reflexive learning.

That is not to say local government is necessarily endowed with these qualities at present. The odds of it becoming so will increase if informed and public spirited individuals get involved in local government as soon as possible, rather than setting their sights on regional or national government. Presiding over contraction will, however, be a thankless task, as constituents will tend to blame those in power for the fact that the pie is shrinking. The job will be a delicate balancing act under very trying circumstances as the fabric os society becomes tattered and torn, but as difficult as it will be, it will remain essential, and getting it right can make a very substantial difference.

Higher levels of government may currently appear to be the relevant seats of power, but are far less likely to be as important in a period of crisis as their response time is far too slow. It is possible that higher levels of government may temporarily be involved in useful rationing programmes, but beyond a certain point, the most important initiatives in practice are likely to be those profoundly local. National governments are more likely to generate additional problems rather than solutions, as they crack down on angry populations during an on-going loss of political legitimacy.

Given the fragility of trade in the future we are facing, programmes of import substitution could be useful, if there would be time to implement them before financial crisis deepens too substantially for the necessary larger-scale organizational capacity to fucntion. Being able to provide for the essentials, without having to rely on vulnerable international supply chains, is extremely beneficial, and food sovereignty in particular is critical.

Once trade withers, we will once again see tremendous regional disparities of fortune, based on differing local circumstances. It would be wise to research in advance what one’s own local circumstances are likely to be, in order to work out in advance how one might live within local limits. Getting expectations aligned with what reality can hope to deliver is a major part of adaptation without unnecessary stress.

In the longer term, we can expect to move through economic depression into some form of relative recovery, although we may see large scale conflict first, and will not, in any case, see a return to present circumstances. We will instead be adapting to the age of limits, mostly in an ad hoc manner due to on-going instability and consequent inability to plan for the long term. The bursting of a bubble on the scale of the one we have experienced has far reaching consequences that are likely to be felt for decades at least. In addition, our current condition of extreme carrying capacity overshoot means that we will actively be tightening our own limits, even as the population declines, by further cannibalizing remaining natural capital.

The operating system reboot which could lead to relative recovery would involve the restoration of some level of trust in the financial system, following the elimination of the huge mass of excess claims to underlying real wealth, and very likely the subsequent destabliization of a currency hyperinflation some years later (timeframe location dependent). We are very likely to see financial innovation, which is nothing more than another name for ponzi scheme, banned for a very long time, and likely the creation of money as interest bearing debt as well.

Humanity is in the habit of locking the door after the horse has bolted, so to speak, only restoring financial regulatory controls once it is too late. Once restored, regulations requiring plain vanilla finance will probably persist until we have once again had time to forget the inevitable consequences of laissez faire. This will be measured in generations.

The small-scale initiatives which we need to navigate the crunch period could be scaled up as trust is slowly re-established. The speed at which this might happen, and the scale that might eventually be workable, are unclear, but it is not likely to be a rapid process, and scale is likely to remain small relative to today. Society will be lower-energy and therefore significantly simpler by then, with far smaller concentrations of population.

While some fossil fuels will no doubt be used for essential functions for quite some time to come, the majority of society will be excluded from what remains of the hydrocarbon age. We will likely have renewable energy systems, but not in the form of photovoltaic panels and high-tech electricity systems. Diffuse renewable energy can give us thermal energy, or motive power, or the ability to store energy as compressed air, all relatively simply, but at that point it will not be a technological civilization.

We are heading for a profoundly humbling experience, to put it mildly. Technological man is not the demigod he supposed himself to be, but merely the beneficiary of a fortuitous energy bonanza which temporarily allowed him to turn dreams into reality. We would do well, if we could summon up sufficient humility in advance, to learn from the simple and elegant technologies of the distant past, which we have largely discarded or forgotten.

We could also learn from present day places already constrained by limits – places which already operate simply and on a shoe-string budget both in terms of money and energy. It takes practice to learn to function without the structural dependencies we have constructed for ourselves, and the sooner we begin the learning curve, the better off we will be. Focusing on solution space for our ways forward would save us from countless blind alleys in the meantime.

This is the entire article. Part 1 is here:

Global Financial Crisis – Liquidity Crunch and Economic Depression,

Part 2 is here:

The Psychological Driver of Deflation and the Collapse of the Trust Horizon

Part 3 is here:

Declining Energy Profit Ratio and Socioeconomic Complexity

Part 4 is here:

Blind Alleys and Techno-Fantasies

and part 5 is here:

Solution Space