Raphael The miraculous draught of fishes 1515

There are days, though all too scarce, when very nice surprises come my way. Case in point: yesterday I received a mail from David Holmgren after a long period of radio silence. Australia’s David is one of the fathers of permaculture, along with Bill Mollison, for those few who don’t know him. They first started writing about the concept in the 1970s and never stopped.

Dave calls himself “permaculture co-originator” these days. Hmm. Someone says: “one of the pioneers of modern ecological thinking”. That’s better. No doubt there. These guys taught many many thousands of people how to be self-sufficient. Permaculture is a simple but intricate approach to making sure that the life in your garden or backyard, and thereby your own life, moves towards balance.

My face to face history with David is limited, we spent some time together on two occasions only, I think, in 2012 a day at his home (farm) in Australia and in 2015 -a week- in Penguin, Tasmania at a permaculture conference where the Automatic Earth’s Nicole Foss was one of the key speakers along with Dave. Still, despite the limited time together I see him as a good and dear friend, simply because he’s such a kind and gracious and wise man.

In his mail, David asked if I would publish this article, which he originally posted on his own site just yesterday under the name “The Apology: From Baby Boomers To The Handicapped Generations”. I went for a shorter title (it’s just our format), but of course I will.

Dave has been an avid reader of the Automatic Earth for the past 11 years, we sort of keep his feet on the ground when they’re not planted and soaking in that same ground: “Reading TAE has helped me keep up to date..”

In light of the children’s climate protests today, which I have yet to voice my qualms about (and I have a few), it only makes sense to put into words a baby boomer’s apology. To have that phrased by someone with the intellect and integrity of David should have everyone sit up and pay attention, if you ask me. And perhaps it would be good if more people would try and do the same: apologize to those kids.

Here’s my formidable friend David Holmgren:

David Holmgren: It is time for us baby boomers to honestly acknowledge what we did and didn’t do with the gifts given to us by our forebears and be clear about our legacy with which we have saddled the next and succeeding generations.

By ‘baby boomers’ I mean those of us born in the affluent nations of the western world between 1945 and 1965. In these countries, the majority of the population became middle class beneficiaries of mass affluence. I think of the high birth rate of those times as a product of collective optimism about the future, and the abundant and cheap resources to support growing families.

By many measures, the benefits of global industrial civilisation peaked in our youth, but for most middle class baby boomers of the affluent countries, the continuing experience of those benefits has tended to blind us to the constriction of opportunities faced by the next generations: unaffordable housing and land access, ecological overshoot and climate chaos amongst a host of other challenges.

I am a white middle class man born in 1955 in Australia, one of the richest nations of the ‘western world’ in the middle of the baby boom, so I consider myself well placed to articulate an apology on behalf of my generation.

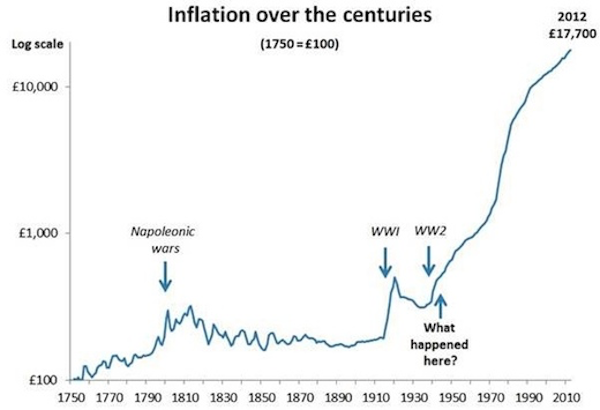

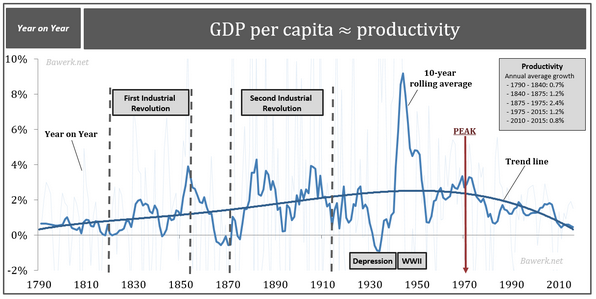

In the life of a baby boomer born in 1950 and dying in 2025 (a premature death according to the expectations of our generation), the best half the world’s endowment of oil – the potent resource that made industrial civilisation possible – will have been burnt. This is tens of millions of years of stored sunlight from a special geological epoch of extraordinary biological productivity. Beyond our basic needs, we have been the recipients of manufactured wants and desires. To varying degrees, we have also suffered the innumerable downsides, addictions and alienations that have come with fossil-fuelled consumer capitalism.

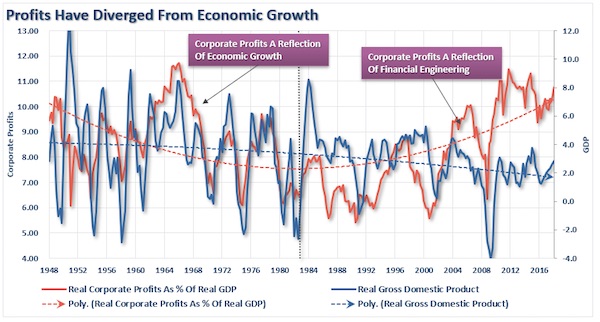

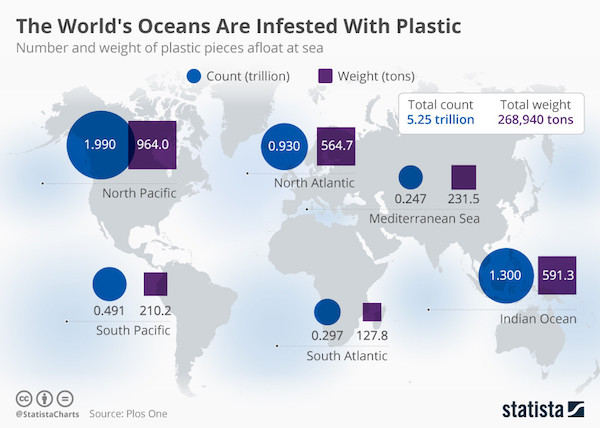

It is also true that our generation has used the genie of fossil fuels to create wonders of technology, organisation and art, and a diversity of lifestyles and ideas. Some of the unintended consequences of our way of life, ranging from antibiotic resistance to bubble economics, should have been obvious, while others, such as the depression epidemic in rich countries, were harder to foresee. Our travel around the world has broadened our minds, but global tourism has contaminated the amazing diversity of nature and traditional cultures at an accelerating pace. We have the excuse that innovations always have pluses and minuses, but it seems we have got a larger share of the pluses and handballed more of the minuses to the world’s poorest countries and to our children and grandchildren.

We were the first generation to have the clear scientific evidence that emergent global civilisation was on an unsustainable path that would precipitate an unravelling of both nature and society through the 21st century. Although climate chaos was a less obvious outcome than the no-brainer of resource depletion, international recognition of the reality of climate change came way back in 1988, just as we were beginning to get our hands on the levers of power, and we have presided over decades of policies that have accelerated the problem.

Over the years since, the adverse outcomes have shifted from distant risks to lived realities. These impact hardest on the most vulnerable peoples of the world who have yet to taste the benefits of the carbon bonanza that has driven the accelerating climate catastrophe. For the failure to share those benefits globally and curb our own consumption we must be truly sorry.

David Holmgren

In the 1960s and 70s, during our coming of age, a significant proportion of us were critical of what was being passed down to us by our parent’s generation who were also the beneficiaries of the western world system, which some of us baby boomers recognised as a global empire. But our grandparents and parents had been shaped by the rigours and grief of the first global depression of the 1890s, the First World War, The Great Depression of the 1930s and, of course, the Second World War. Aside from those who served in Vietnam, we have cruised through life avoiding the worst threats of nuclear annihilation and economic depression, even as people in other countries suffered the consequences of superpower proxy wars, coups, and economic and environmental catastrophes.

While some of us were burnt by personal and global events, we have mostly led a charmed existence and had the privilege to question our upbringing and culture. We were the first generation in history to experience an extended adolescence of experimentation and privilege with little concern or responsibility for our future, our kin or our country.

Most baby boomers were raised in families where commuting was the norm for our fathers but a home-based lifestyle was still a role model we got from our mothers. In our enthusiasm for women to have equal access to productive work in the monetary economy, few of us noticed that without work to keep the household economy humming we lost much of our household autonomy to market forces. By our daily commutes, mostly alone in our cars, we entrenched this massively wasteful and destructive action as normal and inevitable.

As we came into our power in middle age, the new technology of the internet, workshop tool miniaturisation and other innovations provided more options to participate in the monetary economy without the need to commute, but our generation continued with this insane collective addiction. In Australia, we faithfully followed the American model of not investing in public transport, which moderated the adverse impacts of commuting in European and other countries not so structurally addicted to road transport. By failing to build decent public transport and the opportunities for home-based work, and wasting wealth in a frenzy of freeway building that has choked our cities, our generation has consumed our grandchildren’s inheritance of high quality transport fuels and accelerated the onset of climate chaos. For this we are truly sorry.

In pioneering the double income family, some of us set the pattern for the next generation’s habit of outsourcing the care of children at a young age, making commuting five days a week an early childhood experience. This has left the next generation unable to imagine a life that doesn’t involve leaving home each day.

These patterns are part of a larger crisis created by the double income, debt-laden households with close to 100% dependence on the monetary economy. Without robust and productive household economies, our children and grandchildren’s generations will become the victims of savage disruptions and downturns in the monetary economy. For failing to maintain and strengthen the threads of self-provision, frugality and self-reliance most of us inherited from our parents, we should be truly sorry.

Some of us felt in our hearts that we needed to create a different and better world. Some of us saw the writing on the walls of the world calling for global justice. Some of us read the evidence (mostly clearly in the 1972 Limits To Growth) that attempting to run continuous material growth on finite planet would end in more than tears.

Some of us even rejected the legacy of previous generations of radicals’ direct action against the problems of the world, and instead decided we would boldly create the world we wanted by living it each day. In doing so, we experienced hard-won lessons and even created some hopeful models for succeeding generations to improve on in more difficult conditions. That our efforts at novel solutions often created more sound than substance, or that we flitted from one issue to another rather than doing the hard yards necessary to pass on truly robust design solutions for a world of less, leaves some of us with regrets for which we might also feel the need to apologise.

These experiences are shared to some degree by a minority in all generations but there is significant evidence that the 1960s and 70s was a time when awareness of the need for change was stronger. Unfortunately, a sequence of titanic geopolitical struggles that few of us understand even today, a debt-fuelled version of consumer capitalism, and propaganda against both the Limits to Growth and the values of the counterculture, saw most of us following the neoliberal agenda like sheep into the 1980s and beyond.

After having played with the privilege of free tertiary education, most of us fell for the propaganda and sent our children off to accumulate debts and doubtful benefits in the corporatised businesses that universities became. We convinced our children they needed more specialised knowledge poured down their throats rather than using their best years to build the skills and resilience for the challenges our generation was bequeathing to them. For this we must be truly sorry.

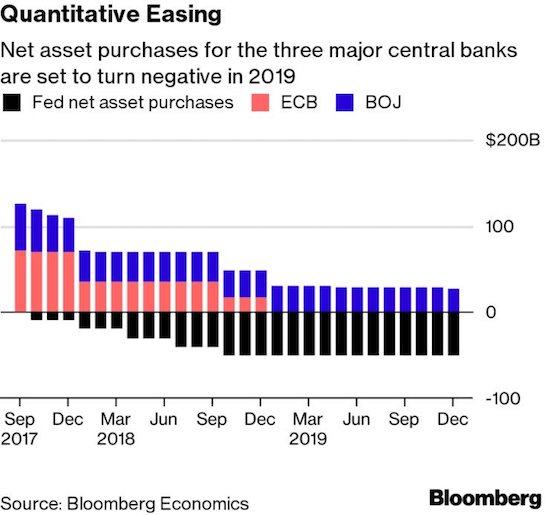

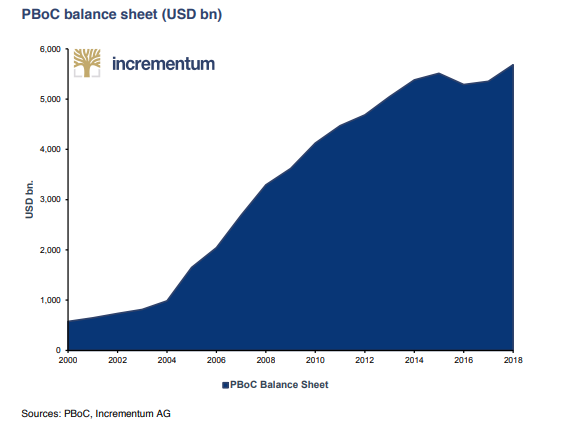

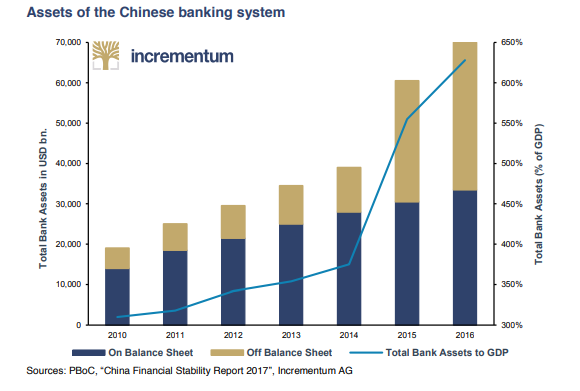

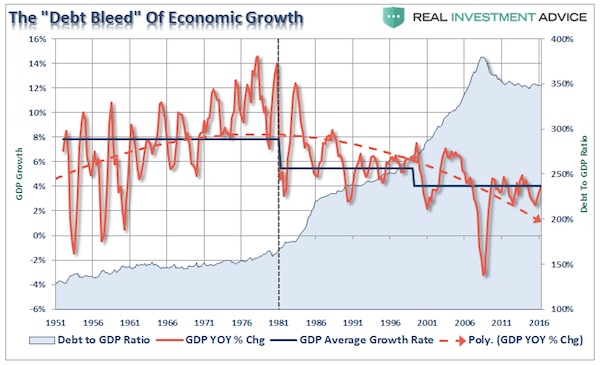

Many of us have been the beneficiaries of buying real estate before the credit-fuelled final stages of casino capitalism made that option a recipe for debt slavery for our children. Without understanding its mechanics we have contributed to – and fuelled with our faith – a bubble economy on a vast scale that can only end in pain and suffering for the majority. While some of us are members of the bank of Mum and Dad, when the property bubble bursts we could find ourselves following the bank chiefs apologising for the debt burden we encouraged our children to take on. Some of us will also have to apologise for losing the family home when we went guarantor on their mortgages. For not heeding the warnings we got with the GFC, we will be truly sorry.

Some of us have used our windfall wealth from real estate and the stock market to do good works, including creating small models of more creative and lower footprint futures that have inspired the minority of the next generations who can also see the writing on the wall. But most of us used our houses as ATMs for new forms of consumption that were unimaginable to our parents, from holidays around the world to endless renovations and a constant flow of updated digital gadgets and virtual diversions. For this frivolous squandering of our windfall wealth we must be truly sorry.

While our parents’ generation experienced the risks of youth through adversity and war we used our privilege to tackle challenges of our own choosing. Although some of us had to struggle to free ourselves from the cloying cocoon of middle class upbringing, we were the generation that flew like the birds and hitchhiked around the country and the world. How strange that on becoming parents (many of us in middle age) we believed the propaganda that the world was too dangerous for our children to do the same around the local neighbourhood. Instead we coddled them, got into the chauffeuring business, and in doing so encouraged their disconnection from both nature and community. As we see our grandchildren’s generation raised in a way that makes them an even more handicapped generation, we must be truly sorry for the path we took and the dis-ease we created.

After so many of us experimented with mind-expanding plants and chemicals, some of us were taken down in chemical addictions, but it was dysfunctional and corrupt legal prohibitions more than the substances themselves that were to blame for the worst of the damage. So how strange that when in middle age we got our hands on the levers of power, most of our generation decided to continue to support the madness of prohibition. For this we must be truly sorry: to have seen the light but then continued to inflict this burden on our children and grandchildren. For having acquiesced in the global ‘war on drugs’ that spread pain and suffering to some of the poorest peoples of the world we should be ashamed.

When the ‘war on drugs’ (a war against substances!) became the model for the ‘war on terror’ (war against a concept!) some of us reawakened the anti-war activism of the Vietnam years but in the end we mostly acquiesced to an agenda of trashing international law, regime change, shock and awe, chaos, and the death of millions; all justified by the 9/11 demolition fireworks that killed a small fraction of the number of citizens that die each year as a result of our ongoing addiction to personal motorised mobility.

While the shadow cast by climate change darkens our grandchilden’s future, the shadow of potential nuclear winter that hung over our childhood as not gone away. Many of us were at the forefront of the international movement to rid the world of nuclear weapons and thought the collapse of the Soviet Union had saved us from that threat. Coming into our power after the end of the cold war, our greatest crime on this geopolitical front has perhaps been the tacit support of our generation for first, the economic rape of Russia in the 1990s, and then its progressive encirclement by the relentless expansion of NATO. In Australia we have meekly added our resources and youth to more or less endless wars in the Middle East and central Asia justified by the fake ‘war on terror’. For this weakness as accessories to global crimes wasting wealth and lives to consolidate the western powers’ control of the first truly global empire, we should hang our collective heads in shame.

While some of our generation’s intellectuals continued to critique the ‘war on terror’ as fake, the vast majority of the public intellectuals of our generation, including those on the left, have supported the rapid rise of Cold War 2.0 to contain Russia, China and any other country that doesn’t accept what we now call ‘the rules based international order’ (code for ‘our empire’). This is truly astonishing when looked at in the context of our lived history. Let us hope that sanity can prevail as our empire fades and future generations don’t brand us as the most insane, war-mongering generation of all time. For our complicity in this grand failure of resistance we should be truly sorry.

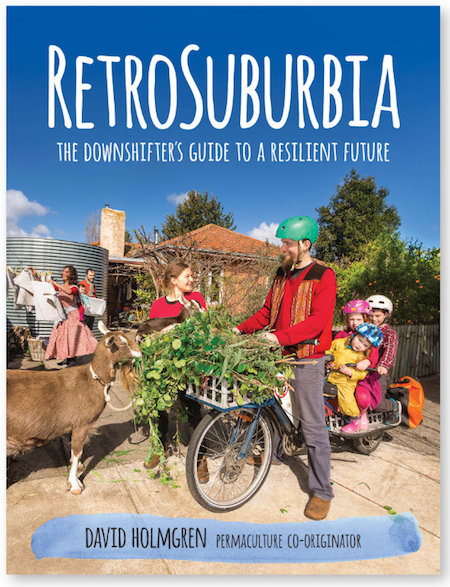

click to order David’s latest

On another equally titanic front, the mistake of giving legal personhood to corporations was not one that our generation made. However most of us have contributed our work, consumption and capital to assist these self-organising, profit-maximising, cost-minimising machines of capitalism morphing into emergent new life forms that threaten to consume both nature and humanity in an algorithmic drive for growth. At a time of our seniority and numbers, we failed to use the Global Financial Crisis as an opportunity to bring these emergent monsters to heel. Do our children have the capacity to tame the monsters that we nurtured from fragile infants to commanding masters?

And if they do find the will to withdraw their work, consumption and capital enough to contain the corporations, will the economy that currently provides for both needs and wants unravel completely? This is a burden so great most of us continue to believe we have no responsibility or agency in such a dark reality. We trust that history will not place the burden of responsibility on our generation alone. But for our part in this failure of agency over human affairs we apologise. Further, we should accept with grace the consequences for our own wellbeing.

Most of us feel impotent when thinking of these failures to control the excesses of our era, but on a more modest scale we have mindlessly participated in taking the goods and passing on the debt to future generations. No more so than in our habitual acceptance of antibiotics from doctors to fix the most mundane of illnesses. For our parents’ generation, antibiotics represented the peak of medical science’s ability to control what killed so many of their parents and earlier generations.

For us, they became routine tools to keep us on the job and our children not missing precious days at school. Through this banal practice we have unwittingly conspired with our doctors to rapidly breed resistance to the most effective and low-cost antibiotics. We took for granted that future generations would always be able to work out ways to keep ahead of diseases with an endless string of new antibiotics. For having squandered this gift we are truly sorry.

Further, despite the fact that some of us have became vegetarian or even vegan, our generation’s demand for cheap chicken and bacon has driven the industrial dosing of animals with antibiotics on a scale that has accelerated the development of antibiotic resistance far faster than would have been the case from us dosing ourselves and our children. For supporting this and other such obscene systems of animal husbandry we apologise to our grandchildren and succeeding generations and hope that somehow an accommodation between humanity, animals and microbes is still possible.

We experienced and benefited from the emergent culture of rights and recognition for women, minorities and the people of varied abilities, and many of us who fought to extend and deepen those rights have pride in what we did. However some of us are beginning to fear that in doing so we contributed to creating new demands, disabilities, and fractious subcultures of fear and angst unimagined in previous generations. While we might not be in the driving seat of identity politics and culture wars, we raised our children to demand their rights in a world that is unravelling due to its multiple contradictions.

In this emerging context, strident demands for rights are likely to be a waste of valuable energy that younger people might better focus on becoming useful to themselves and others. For overemphasising the demand for rights and underplaying the need for responsible self- and collective-reliance, perhaps we should also be sorry.

And is this escalating demand for rights by younger people itself connected, even peripherally, to the increasing callous disregard for the rights of others? Especially in the case of refugees, this careless disregard has allowed political elites to use tough treatment of the less fortunate to distract from the gradual loss of shared privilege that once characterised the ‘lucky country’. To the shame of those in power over the last two decades (mostly baby boomers) those policies are now being adopted on a larger scale in Europe and the US.

In our lifetimes religious faith has declined. For many of our generation, this change represents a measure of humanity’s progress from a benighted past to a promising future. But the collective belief in science and evidence-based decision making has now become a new faith, “Scientism”, which seeks to drive out all other ways of thinking and being from the public space. At the same time, religious fundamentalism is now resurgent. Is this too something that our generation unleashed by preaching tolerance while enforcing an ideology we didn’t even recognise as such?

A significant sign of the good intentions of our generation has been our recognition that the ancient war against nature, which has plagued human life since the beginnings of agriculture, and indeed civilisation, must end. One powerful expression of our efforts has been the valuing of the biodiversity of life, especially local indigenous biodiversity. In the ‘New Europes’ of North America and the Antipodes, seeking to save indigenous biodiversity has grown into an institutionalised form of atonement for the sins of the forefathers.

While this seems like one of our achievements, even this we have bastardised with a new war against naturalised biodiversity. Perhaps the worst aspect of this renewed war against novel ecologies is that we have accepted the helping hand of Monsanto in using Roundup as the main weapon in our urban and rural habitats. The mounting evidence that Roundup may be worse than DDT will be part of our legacy. While history may excuse our parent’s generation for naïve optimism in relation to DDT, our generation’s version of the war on nature will not save us from harsh judgement. For this we should be truly sorry.

Of course any public apology in this country invites comparisons to the apology by governments to the stolen generation of Australian indigenous peoples for the wrongs of the past. This unfinished sorry business is beyond the scope of this apology, but it is an opportunity to reflect critically on our common self-perception of supporting indigenous peoples’ rights in contrast to the normalised racism of previous generations.

Our generation’s invitation to, and enabling of, Australians of indigenous descent to more fully participate in mainstream Australian society may have been a necessary step towards reconciliation; or could it have been a poison chalice drawing them even deeper into the dysfunctions of industrial modernity that I have already outlined. We can only hope that people with such a history of resilience and understanding in the face dispossession will take these additional burdens in their stride.

In any case, this apology is not one that comes from a position of invulnerable privilege, giving succour to those who are no threat to that privilege. For many baby boomers, now caring for parents and dealing with their deaths, we are more inwardly focused. For some of us, especially those estranged from parents, through this both painful and tender processes we are finally growing up. But a comic tragedy could play out in our declining years if a combination of novel disabilities, the culture of rights and amplified fears lead to our children and grandchildren’s generations mostly experiencing harder times as far worse than they might really be, and deciding we are the cause of their troubles.

We baby boomers will increasingly find that in our growing dependence on young people we will be subject to their perspectives, whims and prejudices. Hopefully we can take what we are given on the chin and along with our children and our grandchildren’s generations we can all grow up and work together to face the future with whatever capacities we have.

We might hope this apology is itself a wake-up call to the younger generations that are still mostly sleepwalking into the oncoming maelstroms. In raising the alarm we might hope our humble apology will galvanise the potential in young people who are grasping the nettle of opportunities to turn problems into solutions.

We hope that this apology might lead to understanding rather than resentment of our frailty in the face of the self-organising forces of powerful change that have driven the climaxing of global industrial civilisation. Finally, the task ahead for our generation is to learn how to downsize and disown before we prepare to die, with grace, at a time of our choosing, and in a way that inspires and frees the next generations to chart a prosperous way down.