The Statue of Liberty at the 1878 Paris World’s Fair

This article by Nicole Foss was published earlier at the Automatic Earth in 4 chapters.

Part 1 is here: Negative Interest Rates and the War on Cash (1)

Part 2 is here: Negative Interest Rates and the War on Cash (2)

Part 3 is here: Negative Interest Rates and the War on Cash (3)

Part 4 is here: Negative Interest Rates and the War on Cash (4)

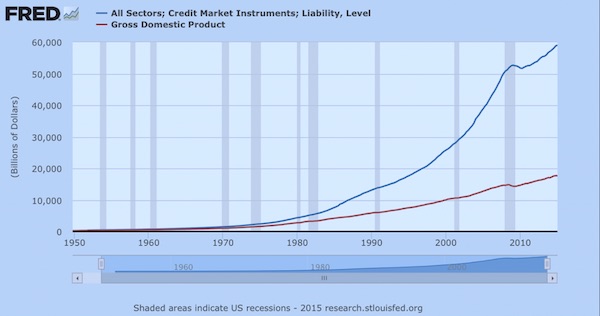

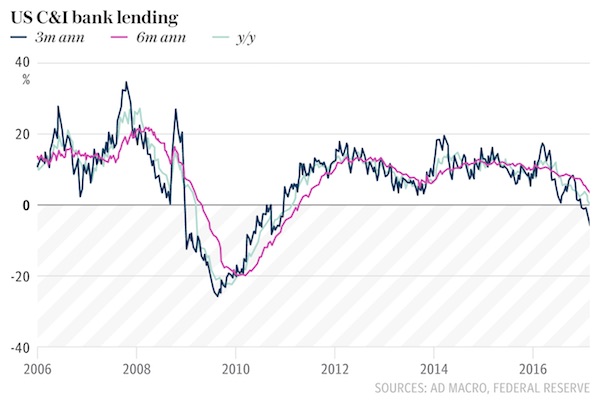

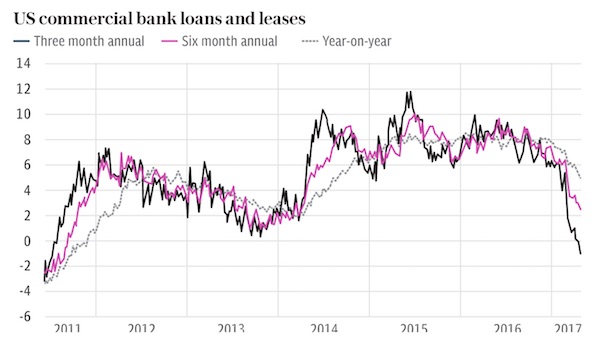

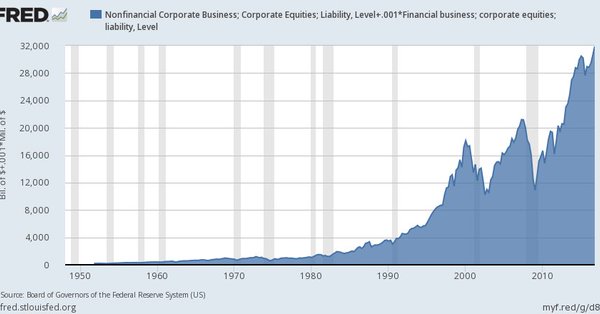

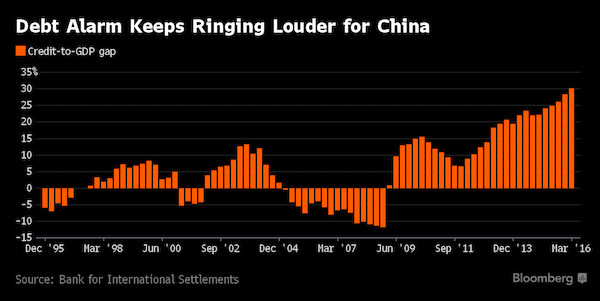

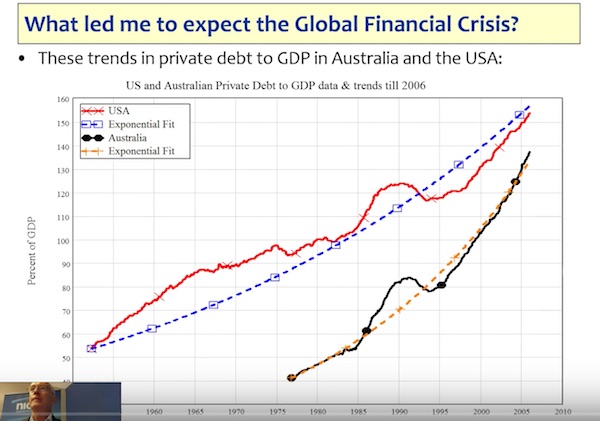

Nicole Foss: As momentum builds in the developing deflationary spiral, we are seeing increasingly desperate measures to keep the global credit ponzi scheme from its inevitable conclusion. Credit bubbles are dynamic — they must grow continually or implode — hence they require ever more money to be lent into existence. But that in turn requires a plethora of willing and able borrowers to maintain demand for new credit money, lenders who are not too risk-averse to make new loans, and (apparently effective) mechanisms for diluting risk to the point where it can (apparently safely) be ignored. As the peak of a credit bubble is reached, all these necessary factors first become problematic and then cease to be available at all. Past a certain point, there are hard limits to financial expansions, and the global economy is set to hit one imminently.

Borrowers are increasingly maxed out and afraid they will not be able to service existing loans, let alone new ones. Many families already have more than enough ‘stuff’ for their available storage capacity in any case, and are looking to downsize and simplify their cluttered lives. Many businesses are already struggling to sell goods and services, and so are unwilling to borrow in order to expand their activities. Without willingness to borrow, demand for new loans will fall substantially. As risk factors loom, lenders become far more risk-averse, often very quickly losing trust in the solvency of of their counterparties. As we saw in 2008, the transition from embracing risky prospects to avoiding them like the plague can be very rapid, changing the rules of the game very abruptly.

Mechanisms for spreading risk to the point of ‘dilution to nothingness’, such as securitization, seen as effective and reliable during monetary expansions, cease to be seen as such as expansion morphs into contraction. The securitized instruments previously created then cease to be perceived as holding value, leading to them being repriced at pennies on the dollar once price discovery occurs, and the destruction of that value is highly deflationary. The continued existence of risk becomes increasingly evident, and the realisation that that risk could be catastrophic begins to dawn.

Natural limits for both borrowing and lending threaten the capacity to prolong the credit boom any further, meaning that even if central authorities are prepared to pay almost any price to do so, it ceases to be possible to kick the can further down the road. Negative interest rates and the war on cash are symptoms of such a limit being reached. As confidence evaporates, so does liquidity. This is where we find ourselves at the moment — on the cusp of phase two of the credit crunch, sliding into the same unavoidable constellation of conditions we saw in 2008, but on a much larger scale.

From ZIRP to NIRP

Interest rates have remained at extremely low levels, hardly distinguishable from zero, for the several years. This zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) is a reflection of both the extreme complacency as to risk during the rise into the peak of a major bubble, and increasingly acute pressure to keep the credit mountain growing through constant stimulation of demand for borrowing. The resulting search for yield in a world of artificially stimulated over-borrowing has lead to an extraordinary array of malinvestment across many sectors of the real economy. Ever more excess capacity is being built in a world facing a severe retrenchment in aggregate demand. It is this that is termed ‘recovery’, but rather than a recovery, it is a form of double jeopardy — an intensification of previous failed strategies in the hope that a different outcome will result. This is, of course, one definition of insanity.

Now that financial crisis conditions are developing again, policies are being implemented which amount to an even greater intensification of the old strategy. In many locations, notably those perceived to be safe havens, the benchmark is moving from a zero interest rate policy to a negative interest rate policy (NIRP), initially for bank reserves, but potentially for business clients (for instance in Holland and the UK). Individual savers would be next in line. Punishing savers, while effectively encouraging banks to lend to weaker, and therefore riskier, borrowers, creates incentives for both borrowers and lenders to continue the very behaviour that set the stage for financial crisis in the first place, while punishing the kind of responsibility that might have prevented it.

Risk is relative. During expansionary times, when risk perception is low almost across the board (despite actual risk steadily increasing), the risk premium that interest rates represent shows relatively little variation between different lenders, and little volatility. For instance, the interest rates on sovereign bonds across Europe, prior to financial crisis, were low and broadly similar for many years. In other words, credit spreads were very narrow during that time. Greece was able to borrow almost as easily and cheaply as Germany, as lenders bet that Europe’s strong economies would back the debt of its weaker parties. However, as collective psychology shifts from unity to fragmentation, risk perception increases dramatically, and risk distinctions of all kinds emerge, with widening credit spreads. We saw this happen in 2008, and it can be expected to be far more pronounced in the coming years, with credit spreads widening to record levels. Interest rate divergences create self-fulfilling prophecies as to relative default risk, against a backdrop of fear-driven high volatility.

Many risk distinctions can be made — government versus private debt, long versus short term, economic centre versus emerging markets, inside the European single currency versus outside, the European centre versus the troubled periphery, high grade bonds versus junk bonds etc. As the risk distinctions increase, the interest rate risk premiums diverge. Higher risk borrowers will pay higher premiums, in recognition of the higher default risk, but the higher premium raises the actual risk of default, leading to still higher premiums in a spiral of positive feedback. Increased risk perception thus drives actual risk, and may do so until the weak borrower is driven over the edge into insolvency. Similarly, borrowers perceived to be relative safe havens benefit from lower risk premiums, which in turn makes their debt burden easier to bear and lowers (or delays) their actual risk of default. This reduced risk of default is then reflected in even lower premiums. The risky become riskier and the relatively safe become relatively safer (which is not necessarily to say safe in absolute terms). Perception shapes reality, which feeds back into perception in a positive feedback loop.

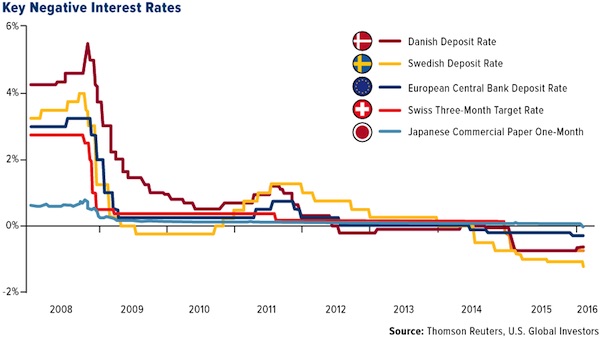

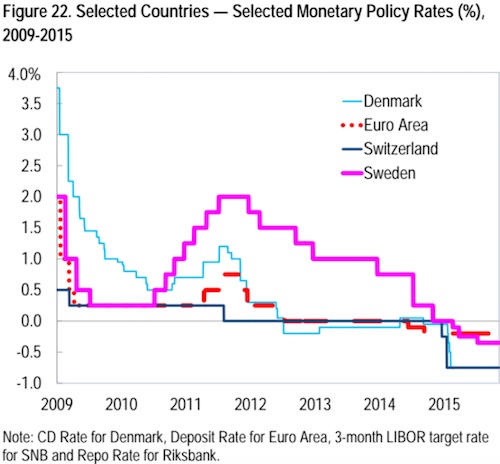

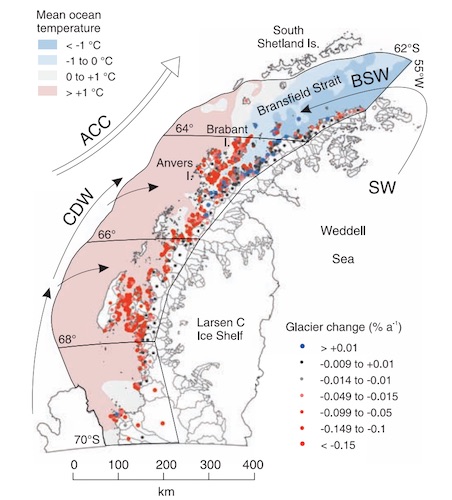

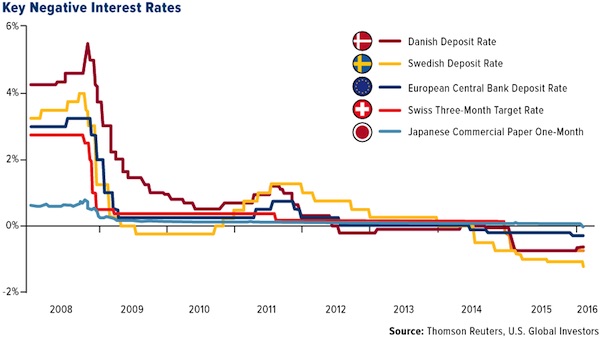

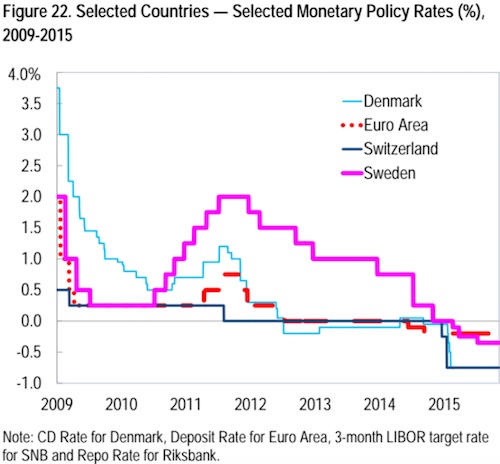

The process of diverging risk perception is already underway, and it is generally the states seen as relatively safe where negative interest rates are being proposed or implemented. Negative rates are already in place for bank reserves held with the ECB and in a number of European states from 2012 onwards, notably Scandinavia and Switzerland. The desire for capital preservation has led to a willingness among those with capital to accept paying for the privilege of keeping it in ‘safe havens’. Note that perception of safety and actual safety are not equivalent. States at the peak of a bubble may appear to be at low risk, but in fact the opposite is true. At the peak of a bubble, there is nowhere to go but down, as Iceland and Ireland discovered in phase one of the financial crisis, and many others will discover as we move into phase two. For now, however, the perception of low risk is sufficient for a flight to safety into negative interest rate environments.

This situation serves a number of short term purposes for the states involved. Negative rates help to control destabilizing financial inflows at times when fear is increasingly driving large amounts of money across borders. A primary objective has been to reduce upward pressure on currencies outside the eurozone. The Swiss, Danish and Swedish currencies have all been experiencing currency appreciation, hence a desire to use negative interest rates to protect their exchange rate, and therefore the price of their exports, by encouraging foreigners to keep their money elsewhere. The Danish central bank’s sole mandate is to control the value of the currency against the euro. For a time, Switzerland pegged their currency directly to the euro, but found the cost of doing so to be prohibitive. For them, negative rates are a less costly attempt to weaken the currency without the need to defend a formal peg. In a world of competitive, beggar-thy-neighbour currency devaluations, negative interest rates are seen as a means to achieve or maintain an export advantage, and evidence of the growing currency war.

Negative rates are also intended to discourage saving and encourage both spending and investment. If savers must pay a penalty, spending or investment should, in theory, become more attractive propositions. The intention is to lead to more money actively circulating in the economy. Increasing the velocity of money in circulation should, in turn, provide price support in an environment where prices are flat to falling. (Mainstream commentators would describe this as as an attempt to increase ‘inflation’, by which they mean price increases, to the common target of 2%, but here at The Automatic Earth, we define inflation and deflation as an increase or decrease, respectively, in the money supply, not as an increase or decrease in prices.) The goal would be to stave off a scenario of falling prices where buyers would have an incentive to defer spending as they wait for lower prices in the future, starving the economy of circulating currency in the meantime. Expectations of falling prices create further downward price pressure, leading into a vicious circle of deepening economic depression. Preventing such expectations from taking hold in the first place is a major priority for central authorities.

Negative rates in the historical record are symptomatic of times of crisis when conventional policies have failed, and as such are rare. Their use is a measure of desperation:

First, a policy rate likely would be set to a negative value only when economic conditions are so weak that the central bank has previously reduced its policy rate to zero. Identifying creditworthy borrowers during such periods is unusually challenging. How strongly should banks during such a period be encouraged to expand lending?

However strongly banks are ‘encouraged’ to lend, willing borrowers and lenders are set to become ‘endangered species’:

The goal of such rates is to force banks to lend their excess reserves. The assumption is that such lending will boost aggregate demand and help struggling economies recover. Using the same central bank logic as in 2008, the solution to a debt problem is to add on more debt. Yet, there is an old adage: you can bring a horse to water but you cannot make him drink! With the world economy sinking into recession, few banks have credit-worthy customers and many banks are having difficulties collecting on existing loans.

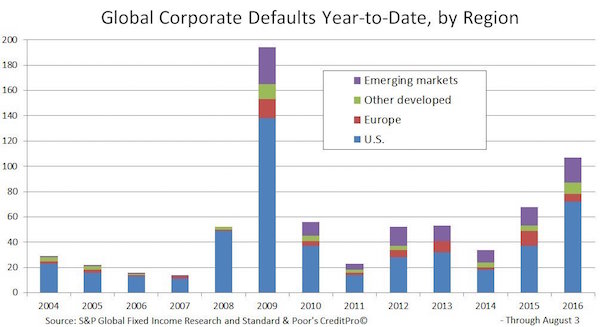

Italy’s non-performing loans have gone from about 5 percent in 2010 to over 15 percent today. The shale oil bust has left many US banks with over a trillion dollars of highly risky energy loans on their books. The very low interest rate environment in Japan and the EU has done little to spur demand in an environment full of malinvestments and growing government constraints.

Doing more of the same simply elevates the already enormous risk that a new financial crisis is right around the corner:

Banks rely on rates to make returns. As the former Bank of England rate-setter Charlie Bean has written in a recent paper for The Economic Journal, pension funds will struggle to make adequate returns, while fund managers will borrow a lot more to make profits. Mr Bean says: “All of this makes a leveraged ‘search for yield’ of the sort that marked the prelude to the crisis more likely.” This is not comforting but it is highly plausible: barely a decade on from the crash, we may be about to repeat it. This comes from tasking central bankers with keeping the world economy growing, even while governments have cut spending.

Experiences with Negative Interest Rates

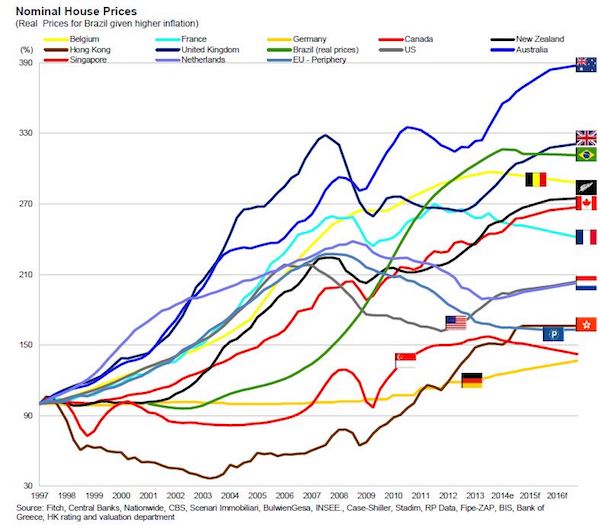

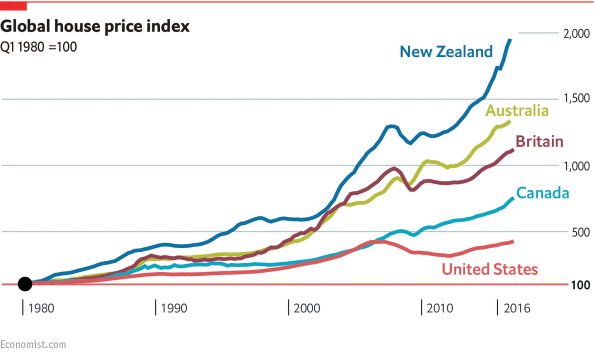

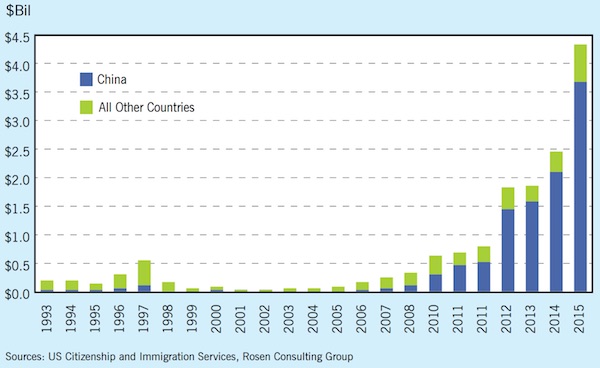

The existing low interest rate environment has already caused asset price bubbles to inflate further, placing assets such as real estate ever more beyond the reach of ordinary people at the same time as hampering those same people attempting to build sufficient savings for a deposit. Negative interest rates provide an increased incentive for this to continue. In locations where the rates are already negative, the asset bubble effect has worsened. For instance, in Denmark negative interest rates have added considerable impetus to the housing bubble in Copenhagen, resulting in an ever larger pool over over-leveraged property owners exposed to the risks of a property price collapse and debt default:

Where do you invest your money when rates are below zero? The Danish experience says equities and the property market. The benchmark index of Denmark’s 20 most-traded stocks has soared more than 100 percent since the second quarter of 2012, which is just before the central bank resorted to negative rates. That’s more than twice the stock-price gains of the Stoxx Europe 600 and Dow Jones Industrial Average over the period. Danish house prices have jumped so much that Danske Bank A/S, Denmark’s biggest lender, says Copenhagen is fast becoming Scandinavia’s riskiest property market.

Considering that risky property markets are the norm in Scandinavia, Copenhagen represents an extreme situation:

“Property prices in Copenhagen have risen 40–60 percent since the middle of 2012, when the central bank first resorted to negative interest rates to defend the krone’s peg to the euro.”

This should come as no surprise: recall that there are documented cases where Danish borrowers are paid to take on debt and buy houses “In Denmark You Are Now Paid To Take Out A Mortgage”, so between rewarding debtors and punishing savers, this outcome is hardly shocking. Yet it is the negative rates that have made this unprecedented surge in home prices feel relatively benign on broader price levels, since the source of housing funds is not savings but cash, usually cash belonging to the bank.

The Swedish property market is similarly reaching for the sky. Like Japan at the peak of it’s bubble in the late 1980s, Sweden has intergenerational mortgages, with an average term of 140 years! Recent regulatory attempts to rein in the ballooning debt by reducing the maximum term to a ‘mere’ 105 years have been met with protest:

Swedish banks were quoted in the local press as opposing the move. “It isn’t good for the finances of households as it will make mortgages more expensive and the terms not as good. And it isn’t good for financial stability,” the head of Swedish Bankers’ Association was reported to say.

Apart from stimulating further leverage in an already over-leveraged market, negative interest rates do not appear to be stimulating actual economic activity:

If negative rates don’t spur growth — Danish inflation since 2012 has been negligible and GDP growth anemic — what are they good for?….Danish businesses have barely increased their investments, adding less than 6 percent in the 12 quarters since Denmark’s policy rate turned negative for the first time. At a growth rate of 5 percent over the period, private consumption has been similarly muted. Why is that? Simply put, a weak economy makes interest rates a less powerful tool than central bankers would like.

“If you’re very busy worrying about the economy and your job, you don’t care very much what the exact rate is on your car loan,” says Torsten Slok, Deutsche Bank’s chief international economist in New York.

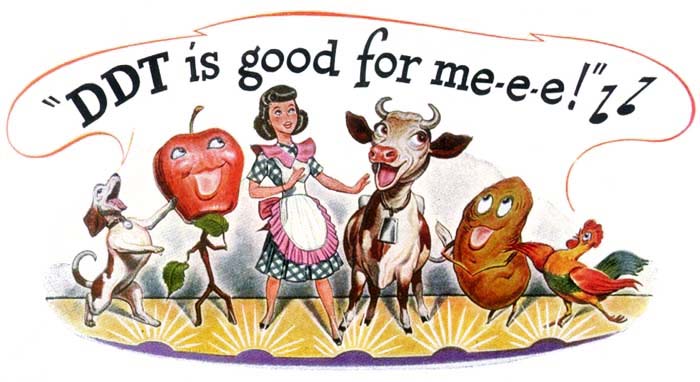

Fuelling inequality and profligacy while punishing responsible behaviour is politically unpopular, and the consequences, when they eventually manifest, will be even more so. Unfortunately, at the peak of a bubble, it is only continued financial irresponsibility that can keep a credit expansion going and therefore keep the financial system from abruptly crashing. The only things keeping the system ‘running on fumes’ as it currently is, are financial sleight-of-hand, disingenuous bribery and outright fraud. The price to pay is that the systemic risks continue to grow, and with it the scale of the impacts that can be expected when the risk is eventually realised. Politicians desperately wish to avoid those consequences occurring in their term of office, hence they postpone the inevitable at any cost for as long as physically possible.

The Zero Lower Bound and the Problem of Physical Cash

Central bankers attempting to stimulate the circulation of money in the economy through the use of negative interest rates have a number of problems. For starters, setting a low official rate does not necessarily mean that low rates will prevail in the economy, particularly in times of crisis:

The experience of the global financial crisis taught us that the type of shocks which can drive policy interest rates to the lower bound are also shocks which produce severe impairments to the monetary policy transmission mechanism. Suppose, for example, that the interbank market freezes and prevents a smooth transmission of the policy interest rate throughout the banking sector and financial markets at large. In this case, any cut in the policy rate may be almost completely ineffective in terms of influencing the macroeconomy and prices.

This is exactly what we saw in 2008, when interbank lending seized up due to the collapse of confidence in the banking sector. We have not seen this happen again yet, but it inevitably will as crisis conditions resume, and when it does it will illustrate vividly the limits of central bank power to control financial parameters. At that point, interest rates are very likely to spike in practice, with banks not trusting each other to repay even very short term loans, since they know what toxic debt is on their own books and rationally assume their potential counterparties are no better. Widening credit spreads would also lead to much higher rates on any debt perceived to be risky, which, increasingly, would be all debt with the exception of government bonds in the jurisdictions perceived to be safest. Low rates on high grade debt would not translate into low rates economy-wide. Given the extent of private debt, and the consequent vulnerability to higher interest rates across the developed world, an interest rate spike following the NIRP period would be financially devastating.

The major issue with negative rates in the shorter term is the ability to escape from the banking system into physical cash. Instead of causing people to spend, a penalty on holding savings in a banks creates an incentive for them to withdraw their funds and hold cash under their own control, thereby avoiding both the penalty and the increasing risk associated with the banking system:

Western banking systems are highly illiquid, meaning that they have very low cash equivalents as a percentage of customer deposits….Solvency in many Western banking systems is also highly questionable, with many loaded up on the debts of their bankrupt governments. Banks also play clever accounting games to hide the true nature of their capital inadequacy. We live in a world where questionably solvent, highly illiquid banks are backed by under capitalized insurance funds like the FDIC, which in turn are backed by insolvent governments and borderline insolvent central banks. This is hardly a risk-free proposition. Yet your reward for taking the risk of holding your money in a precarious banking system is a rate of return that is substantially lower than the official rate of inflation.

In other words, negative rates encourage an arbitrage situation favouring cash. In an environment of few good investment opportunities, increasing recognition of risk and a rising level of fear, a desire for large scale cash withdrawal is highly plausible:

From a portfolio choice perspective, cash is, under normal circumstances, a strictly dominated asset, because it is subject to the same inflation risk as bonds but, in contrast to bonds, it yields zero return. It has also long been known that this relationship would be reversed if the return on bonds were negative. In that case, an investor would be certain of earning a profit by borrowing at negative rates and investing the proceedings in cash. Ignoring storage and transportation costs, there is therefore a zero lower bound (ZLB) on nominal interest rates.

Zero is the lower bound for nominal interest rates if one would want to avoid creating such an incentive structure, but in a contractionary environment, zero is not low enough to make borrowing and lending attractive. This is because, while the nominal rate might be zero, the real rate (the nominal rate minus negative inflation) can remain high, or perhaps very high, depending on how contractionary the financial landscape becomes. As Keynes observed, attempting to stimulate demand for money by lowering interest rates amounts to ‘pushing on a piece of string‘. Central authorities find themselves caught in the liquidity trap, where monetary policy ceases to be effective:

Many big economies are now experiencing ‘deflation’, where prices are falling. In the euro zone, for instance, the main interest rate is at 0.05% but the “real” (or adjusted for inflation) interest rate is considerably higher, at 0.65%, because euro-area inflation has dropped into negative territory at -0.6%. If deflation gets worse then real interest rates will rise even more, choking off recovery rather than giving it a lift.

If nominal rates are sufficiently negative to compensate for the contractionary environment, real rates could, in theory, be low enough to stimulate the velocity of money, but the more negative the nominal rate, the greater the incentive to withdraw physical cash. Hoarded cash would reduce, instead of increase, the velocity of money. In practice, lowering rates can be moderately reflationary, provided there remains sufficient economic optimism for people to see the move in a positive light. However, sending rates into negative territory at a time pessimism is dominant can easily be interpreted as a sign of desperation, and therefore as confirmation of a negative outlook. Under such circumstances, the incentives to regard the banking system as risky, to withdraw physical cash and to hoard it for a rainy day increase substantially. Not only does the money supply fail to grow, as new loans are not made, but the velocity of money falls as money is hoarded, thereby aggravating a deflationary spiral:

A decline in the velocity of money increases deflationary pressure. Each dollar (or yen or euro) generates less and less economic activity, so policymakers must pump more money into the system to generate growth. As consumers watch prices decline, they defer purchases, reducing consumption and slowing growth. Deflation also lifts real interest rates, which drives currency values higher. In today’s mercantilist, beggar-thy-neighbour world of global trade, a strong currency is a headwind to exports. Obviously, this is not the desired outcome of policymakers. But as central banks grasp for new, stimulative tools, they end up pushing on an ever-lengthening piece of string.

Japan has been in the economic doldrums, with pessimism dominant, for over 25 years, and the population has become highly sceptical of stimulation measures intended to lead to recovery. The negative interest rates introduced there (described as ‘economic kamikaze’) have had a very different effect than in Scandinavia, which is still more or less at the peak of its bubble and therefore much more optimistic. Unfortunately, lowering interest rates in times of collective pessimism has a poor record of acting to increase spending and stimulate the economy, as Japan has discovered since their bubble burst in 1989:

For about a quarter of a century the Japanese have proved to be fanatical savers, and no matter how low the Bank of Japan cuts rates, they simply cannot be persuaded to spend their money, or even invest it in the stock market. They fear losing their jobs; they fear a further fall in shares or property values; they have no confidence in the investment opportunities in front of them. So pathological has this psychology grown that they would rather see the value of their savings fall than spend the cash. That draining of confidence after the collapse of the 1980s “bubble” economy has depressed Japanese growth for decades.

Fear is a very sharp driver of behaviour — easily capable of over-riding incentives designed to promote spending and investment:

When people are fearful they tend to save; and when they become especially fearful then they save even more, even if the returns on their savings are extremely low. Much the same goes for businesses, and there are increasing reports of them “hoarding” their profits rather than reinvesting them in their business, such is the great “uncertainty” around the world economy. Brexit obviously only added to the fears and misgivings about the future.

Deflation is so difficult to overcome precisely because of its strong psychological component. When the balance of collective psychology tips from optimism, hope and greed to pessimism and fear, everything is perceived differently. Measures intended to restore confidence end up being interpreted as desperation, and therefore get little or no traction. As such initiatives fail, their failure becomes conformation of a negative bias, which increases the power of that bias, causing more stimulus initiatives to fail. The resulting positive feedback loop creates and maintains a vicious circle, both economically and socially:

There is a strong argument that when rates go negative it squeezes the speed at which money circulates through the economy, commonly referred to by economists as the velocity of money. We are already seeing this happen in Japan where citizens are clamouring for ¥10,000 bills (and home safes to store them in). People are taking their money out of the banking system to stuff it under their metaphorical mattresses. This may sound extreme, but whether paper money is stashed in home safes or moved into transaction substitutes or other stores of value like gold, the point is it’s not circulating in the economy. The empirical data support this view — the velocity of money has declined precipitously as policymakers have moved aggressively to reduce rates.

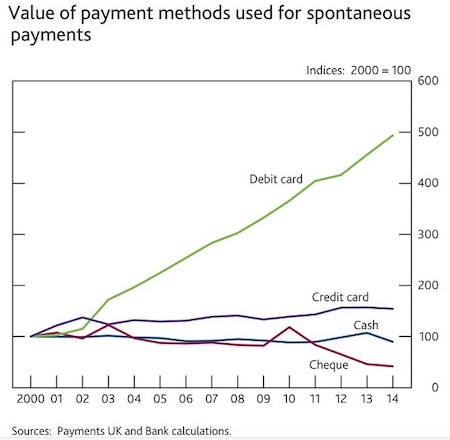

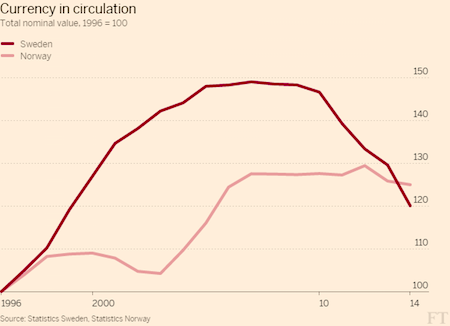

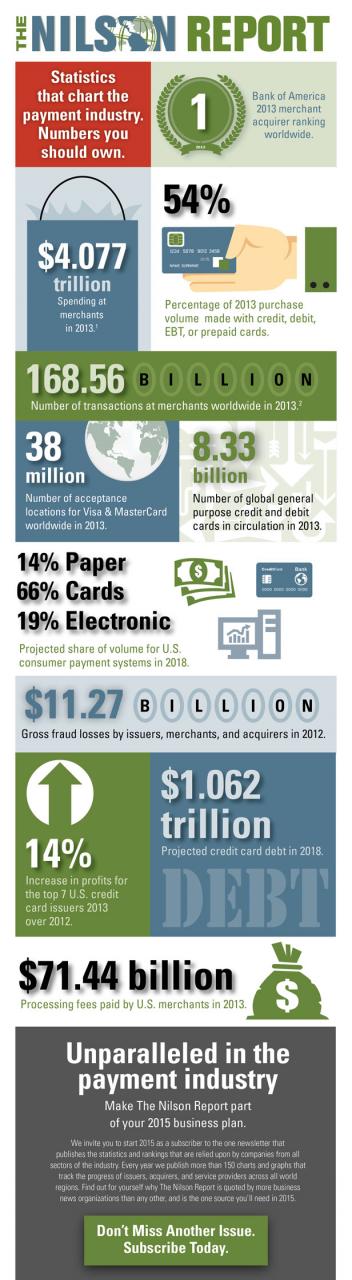

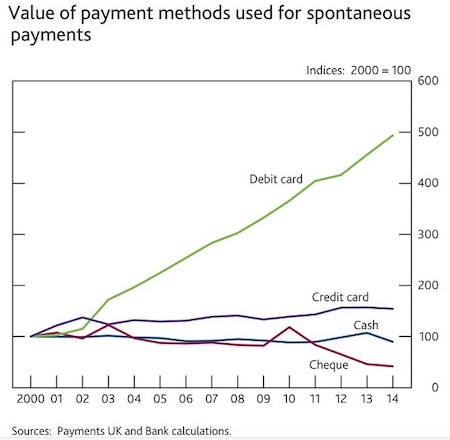

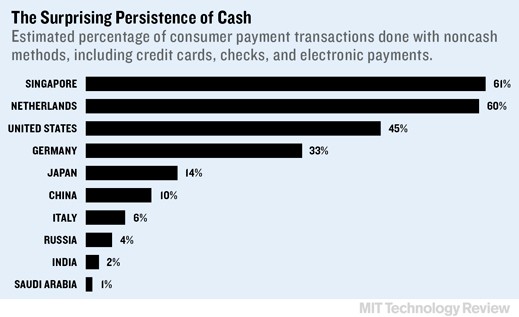

Physical cash under one’s own control is increasingly seen as one of the primary escape routes for ordinary people fearing the resumption of the 2008 liquidity crunch, and its popularity as a store of value is increasing steadily, with demand for cash rising more rapidly than GDP in a wide range of countries:

While cash’s use is in continual decline, claims that it is set to disappear entirely may be premature, according to the Bank of England….The Bank estimates that 21pc to 27pc of everyday transactions last year were in cash, down from between 34pc and 45pc at the turn of the millennium. Yet simultaneously the demand for banknotes has risen faster than the total amount of spending in the economy, a trend that has only become more pronounced since the mid-1990s. The same phenomenon has been seen internationally, in the US, eurozone, Australia and Canada….

….The prevalence of hoarding has also firmed up the demand for physical money. Hoarders are those who “choose to save their money in a safety deposit box, or under the mattress, or even buried in the garden, rather than placing it in a bank account”, the Bank said. At a time when savings rates have not turned negative, and deposits are guaranteed by the government, this kind of activity seems to defy economic theory. “For such action to be considered as rational, those that are hoarding cash must be gaining a non-financial benefit,” the Bank said. And that benefit must exceed the returns and security offered by putting that hoarded cash in a bank deposit account. A Bank survey conducted last year found that 18pc of people said they hoarded cash largely “to provide comfort against potential emergencies”.

This would suggest that a minimum of £3bn is hoarded in the UK, or around £345 a person. A government survey conducted in 2012 suggested that the total number might be higher, at £5bn….

…..But Bank staff believe that its survey results understate the extent of hoarding, as “the sensitivity of the subject” most likely affects the truthfulness of hoarders. “Based on anecdotal evidence, a small number of people are thought to hoard large values of cash.” The Bank said: “As an illustrative example, if one in every thousand adults in the United Kingdom were to hoard as much as £100,000, this would account for around £5bn — nearly 10pc of notes in circulation.” While there may be newer and more convenient methods of payment available, this strong preference for cash as a safety net means that it is likely to endure, unless steps are taken to discourage its use.

Closing the Escape Routes

History teaches us that central authorities dislike escape routes, at least for the majority, and are therefore prone to closing them, so that control of a limited money supply can remain in the hands of the very few. In the 1930s, gold was the escape route, so gold was confiscated. As Alan Greenspan wrote in 1966:

In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through monetary inflation. There is no safe store of value. If there were, the government would have to make its holding illegal, as was done in the case of gold. If everyone decided, for example, to convert all his bank deposits to silver or copper or any other good, and thereafter declined to accept checks as payment for goods, bank deposits would lose their purchasing power and government-created bank credit would be worthless as a claim on goods.

The existence of escape routes for capital preservation undermines the viability of the banking system, which is already over-extended, over-leveraged and extremely fragile. This time cash serves that role:

Ironically, though the paper money standard that replaced the gold standard was originally meant to empower governments, it now seems that paper money is perceived as an obstacle to unlimited government power….While paper money isn’t as big impediment to government power as the gold standard was, it is nevertheless an impediment compared to a society with only electronic money. Because of this, the more ardent statists favor the abolition of paper money and a monetary system with only electronic money and electronic payments.

We can therefore expect cash to be increasingly disparaged in order to justify its intended elimination:

Every day, a situation that requires the use of physical cash, feels more and more like an anachronism. It’s like having to listen to music on a CD. John Maynard Keynes famously referred to gold (well, the gold standard specifically) as a “barbarous relic.” Well the new barbarous relic is physical cash. Like gold, cash is physical money. Like gold, cash is still fetishized. And like gold, cash is a costly drain on the economy. A study done at Tufts in 2013 estimated that cash costs the economy $200 billion. Their study included the nugget that consumers spend, on average, 28 minutes per month just traveling to the point where they obtain cash (ATM, etc.). But this is just first-order problem with cash. The real problem, which economists are starting to recognize, is that paper cash is an impediment to effective monetary policy, and therefore economic growth.

Holding cash is not risk free, but cash is nevertheless king in a period of deflation:

Conventional wisdom is that interest rates earned on investments are never less than zero because investors could alternatively hold currency. Yet currency is not costless to hold: It is subject to theft and physical destruction, is expensive to safeguard in large amounts, is difficult to use for large and remote transactions, and, in large quantities, may be monitored by governments.

The acknowledged risks of holding cash are understood and can be managed personally, whereas the substantial risk associated with a systemic banking crisis are entirely outside the control of ordinary depositors. The bank bail-in (rescuing the bank with the depositors’ funds) in Cyprus in early 2013 was a warning sign, to those who were paying attention, that holding money in a bank is not necessarily safe. The capital controls put in place in other locations, for instance Greece, also underline that cash in a bank may not be accessible when needed.

The majority of the developed world either already has, or is introducing, legislation to require depositor bail-ins in the event of bank failures, rather than taxpayer bailouts, in preparation for many more Cyprus-type events, but on a very much larger scale. People are waking up to the fact that a bank balance is not considered their money, but is actually an unsecured loan to the bank, which the bank may or may not repay, depending on its own circumstances.:

Your checking account balance is denominated in dollars, but it does not consist of actual dollars. It represents a promise by a private company (your bank) to pay dollars upon demand. If you write a check, your bank may or may not be able to honor that promise. The poor souls who kept their euros in the form of large balances in Cyprus banks have just learned this lesson the hard way. If they had been holding their euros in the form of currency, they would have not lost their wealth.

Even in relatively untroubled countries, like the UK, it is becoming more difficult to access physical cash in a bank account or to use it for larger purchases. Notice of intent to withdraw may be required, and withdrawal limits may be imposed ‘for your own protection’. Reasons for the withdrawal may be required, ostensibly to combat money laundering and the black economy:

It’s one thing to be required by law to ask bank customers or parties in a cash transaction to explain where their money came from; it’s quite another to ask them how they intend to use the money they wish to withdraw from their own bank accounts. As one Mr Cotton, a HSBC customer, complained to the BBC’s Money Box programme: “I’ve been banking in that bank for 28 years. They all know me in there. You shouldn’t have to explain to your bank why you want that money. It’s not theirs, it’s yours.”

In France, in the aftermath of terrorist attacks there, several anti-cash measures were passed, restricting the use of cash once obtained:

French Finance Minister Michel Sapin brazenly stated that it was necessary to “fight against the use of cash and anonymity in the French economy.” He then announced extreme and despotic measures to further restrict the use of cash by French residents and to spy on and pry into their financial affairs.

These measures…..include prohibiting French residents from making cash payments of more than 1,000 euros, down from the current limit of 3,000 euros….The threshold below which a French resident is free to convert euros into other currencies without having to show an identity card will be slashed from the current level of 8,000 euros to 1,000 euros. In addition any cash deposit or withdrawal of more than 10,000 euros during a single month will be reported to the French anti-fraud and money laundering agency Tracfin.

Tourists in France may also be caught in the net:

France passed another new Draconian law; from the summer of 2015, it will now impose cash requirements dramatically trying to eliminate cash by force. French citizens and tourists will only be allowed a limited amount of physical money. They have financial police searching people on trains just passing through France to see if they are transporting cash, which they will now seize.

This is essentially the Shock Doctrine in action. Central authorities rarely pass up an opportunity to use a crisis to add to their repertoire of repressive laws and practices.

However, even without a specific crisis to draw on as a justification, many other countries have also restricted the use of cash for purchases:

One way they are waging the War on Cash is to lower the threshold at which reporting a cash transaction is mandatory or at which paying in cash is simply illegal. In just the last few years.

- Italy made cash transactions over €1,000 illegal;

- Switzerland has proposed banning cash payments in excess of 100,000 francs;

- Russia banned cash transactions over $10,000;

- Spain banned cash transactions over €2,500;

- Mexico made cash payments of more than 200,000 pesos illegal;

- Uruguay banned cash transactions over $5,000

Other restrictions on the use of cash can be more subtle, but can have far-reaching effects, especially if the ideas catch on and are widely applied:

The State of Louisiana banned “secondhand dealers” from making more than one cash transaction per week. The term has a broad definition and includes Goodwill stores, specialty stores that sell collectibles like baseball cards, flea markets, garage sales and so on. Anyone deemed a “secondhand dealer” is forbidden to accept cash as payment. They are allowed to take only electronic means of payment or a check, and they must collect the name and other information about each customer and send it to the local police department electronically every day.

The increasing application of de facto capital controls, when combined with the prevailing low interest rates, already convince many to hold cash. The possibility of negative rates would greatly increase the likelihood. We are already in an environment of rapidly declining trust, and limited access to what we still perceive as our own funds only accelerates the process in a self-reinforcing feedback loop. More withdrawals lead to more controls, which increase fear and decrease trust, which leads to more withdrawals. This obviously undermines the perceived power of monetary policy to stimulate the economy, hence the escape route is already quietly closing.

In a deflationary spiral, where the money supply is crashing, very little money is in circulation and prices are consequently falling almost across the board, possessing purchasing power provides for the freedom to pursue opportunities as they present themselves, and to avoid being backed into a corner. The purchasing power of cash increases during deflation, even as electronic purchasing power evaporates. Hence cash represents freedom of action at a time when that will be the rarest of ‘commodities’.

Governments greatly dislike cash, and increasingly treat its use, or the desire to hold it, especially in large denominations, with great suspicion:

Why would a central bank want to eliminate cash? For the same reason as you want to flatten interest rates to zero: to force people to spend or invest their money in the risky activities that revive growth, rather than hoarding it in the safest place. Calls for the eradication of cash have been bolstered by evidence that high-value notes play a major role in crime, terrorism and tax evasion. In a study for the Harvard Business School last week, former bank boss Peter Sands called for global elimination of the high-value note.

Britain’s “monkey” — the £50 — is low-value compared with its foreign-currency equivalents, and constitutes a small proportion of the cash in circulation. By contrast, Japan’s ¥10,000 note (worth roughly £60) makes up a startling 92% of all cash in circulation; the Swiss 1,000-franc note (worth around £700) likewise. Sands wants an end to these notes plus the $100 bill, and the €500 note – known in underworld circles as the “Bin Laden”.

Cash is largely anonymous, untraceable and uncontrollable, hence it makes central authorities, in a system increasingly requiring total buy-in in order to function, extremely uncomfortable. They regard there being no legitimate reason to own more than a small amount of it in physical form, as its ownership or use raises the spectre of tax evasion or other illegal activities:

The insidious nature of the war on cash derives not just from the hurdles governments place in the way of those who use cash, but also from the aura of suspicion that has begun to pervade private cash transactions. In a normal market economy, businesses would welcome taking cash. After all, what business would willingly turn down customers? But in the war on cash that has developed in the thirty years since money laundering was declared a federal crime, businesses have had to walk a fine line between serving customers and serving the government. And since only one of those two parties has the power to shut down a business and throw business owners and employees into prison, guess whose wishes the business owner is going to follow more often?

The assumption on the part of government today is that possession of large amounts of cash is indicative of involvement in illegal activity. If you’re traveling with thousands of dollars in cash and get pulled over by the police, don’t be surprised when your money gets seized as “suspicious.” And if you want your money back, prepare to get into a long, drawn-out court case requiring you to prove that you came by that money legitimately, just because the courts have decided that carrying or using large amounts of cash is reasonable suspicion that you are engaging in illegal activity….

….Centuries-old legal protections have been turned on their head in the war on cash. Guilt is assumed, while the victims of the government’s depredations have to prove their innocence….Those fortunate enough to keep their cash away from the prying hands of government officials find it increasingly difficult to use for both business and personal purposes, as wads of cash always arouse suspicion of drug dealing or other black market activity. And so cash continues to be marginalized and pushed to the fringes.

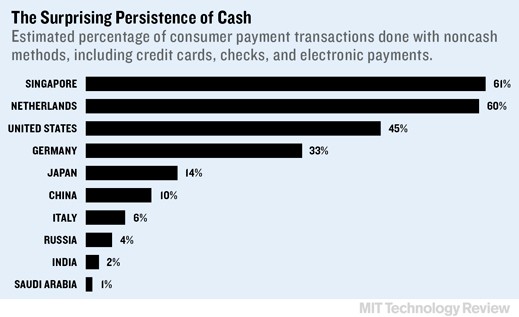

Despite the supposed connection between crime and the holding of physical cash, the places where people are most inclined (and able) to store cash do not conform to the stereotype at all:

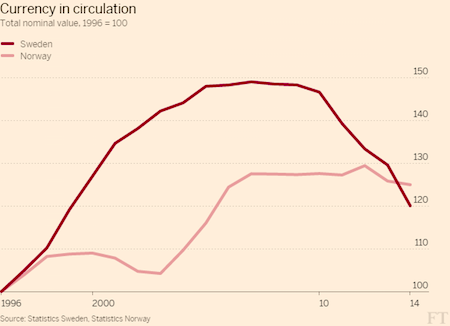

Are Japan and Switzerland havens for terrorists and drug lords? High-denomination bills are in high demand in both places, a trend that some politicians claim is a sign of nefarious behavior. Yet the two countries boast some of the lowest crime rates in the world. The cash hoarders are ordinary citizens responding rationally to monetary policy. The Swiss National Bank introduced negative interest rates in December 2014. The aim was to drive money out of banks and into the economy, but that only works to the extent that savers find attractive places to spend or invest their money. With economic growth an anemic 1%, many Swiss withdrew cash from the bank and stashed it at home or in safe-deposit boxes. High-denomination notes are naturally preferred for this purpose, so circulation of 1,000-franc notes (worth about $1,010) rose 17% last year. They now account for 60% of all bills in circulation and are worth almost as much as Serbia’s GDP.

Japan, where banks pay infinitesimally low interest on deposits, is a similar story. Demand for the highest-denomination ¥10,000 notes rose 6.2% last year, the largest jump since 2002. But 10,000 Yen notes are worth only about $88, so hiding places fill up fast. That explains why Japanese went on a safe-buying spree last month after the Bank of Japan announced negative interest rates on some reserves. Stores reported that sales of safes rose as much as 250%, and shares of safe-maker Secom spiked 5.3% in one week.

In Germany too, negative interest rates are considered intolerable, banks are increasingly being seen as risky prospects, and physical cash under one’s own control is coming to be seen as an essential part of a forward-thinking financial strategy:

First it was the news that Raiffeisen Gmund am Tegernsee, a German cooperative savings bank in the Bavarian village of Gmund am Tegernsee, with a population 5,767, finally gave in to the ECB’s monetary repression, and announced it’ll start charging retail customers to hold their cash. Then, just last week, Deutsche Bank’s CEO came about as close to shouting fire in a crowded negative rate theater, when, in a Handelsblatt Op-Ed, he warned of “fatal consequences” for savers in Germany and Europe — to be sure, being the CEO of the world’s most systemically risky bank did not help his cause.

That was the last straw, and having been patient long enough, the German public has started to move. According to the WSJ, German savers are leaving the “security of savings banks” for what many now consider an even safer place to park their cash: home safes. We wondered how many “fatal” warnings from the CEO of DB it would take, before this shift would finally take place. As it turns out, one was enough….

….“It doesn’t pay to keep money in the bank, and on top of that you’re being taxed on it,” said Uwe Wiese, an 82-year-old pensioner who recently bought a home safe to stash roughly €53,000 ($59,344), including part of his company pension that he took as a payout. Burg-Waechter KG, Germany’s biggest safe manufacturer, posted a 25% jump in sales of home safes in the first half of this year compared with the year earlier, said sales chief Dietmar Schake, citing “significantly higher demand for safes by private individuals, mainly in Germany.”….

….Unlike their more “hip” Scandinavian peers, roughly 80% of German retail transactions are in cash, almost double the 46% rate of cash use in the U.S., according to a 2014 Bundesbank survey….Germany’s love of cash is driven largely by its anonymity. One legacy of the Nazis and East Germany’s Stasi secret police is a fear of government snooping, and many Germans are spooked by proposals of banning cash transactions that exceed €5,000. Many Germans think the ECB’s plan to phase out the €500 bill is only the beginning of getting rid of cash altogether. And they are absolutely right; we can only wish more Americans showed the same foresight as the ordinary German….

….Until that moment, however, as a final reminder, in a fractional reserve banking system, only the first ten or so percent of those who “run” to the bank to obtain possession of their physical cash and park it in the safe will succeed. Everyone else, our condolences.

The internal stresses are building rapidly, stretching economy after economy to breaking point and prompting aware individuals to protect themselves proactively:

People react to these uncertainties by trying to protect themselves with cash and guns, and governments respond by trying to limit citizens’ ability to do so.

If this play has a third act, it will involve the abolition of cash in some major countries, the rise of various kinds of black markets (silver coins, private-label cash, cryptocurrencies like bitcoin) that bypass traditional banking systems, and a surge in civil unrest, as all those guns are put to use. The speed with which cash, safes and guns are being accumulated — and the simultaneous intensification of the war on cash — imply that the stress is building rapidly, and that the third act may be coming soon.

Despite growing acceptance of electronic payment systems, getting rid of cash altogether is likely to be very challenging, particularly as the fear and state of financial crisis that drives people into cash hoarding is very close to reasserting itself. Cash has a very long history, and enjoys greater trust than other abstract means for denominating value. It is likely to prove tenacious, and unable to be eliminated peacefully. That is not to suggest central authorities will not try. At the heart of financial crisis lies the problem of excess claims to underlying real wealth. The bursting of the global bubble will eliminate the vast majority of these, as the value of credit instruments, hitherto considered to be as good as money, will plummet on the realisation that nowhere near all financial promises made can possibly be kept.

Cash would then represent the a very much larger percentage of the remaining claims to limited actual resources — perhaps still in excess of the available resources and therefore subject to haircuts. Not only the quantity of outstanding cash, but also its distribution, may not be to central authorities liking. There are analogous precedents for altering legal currency in order to dispossess ordinary people trying to protect their stores of value, depriving them of the benefit of their foresight. During the Russian financial crisis of 1998, cash was not eliminated in favour of an electronic alternative, but the currency was reissued, which had a similar effect. People were required to convert their life savings (often held ‘under the mattress’) from the old currency to the new. This was then made very difficult, if not impossible, for ordinary people, and many lost the entirety of their life savings as a result.

A Cashless Society?

The greater the public’s desire to hold cash to protect themselves, the greater will be the incentive for central banks and governments to restrict its availability, reduce its value or perhaps eliminate it altogether in favour of electronic-only payment systems. In addition to commercial banks already complicating the process of making withdrawals, central banks are actively considering, as a first step, mechanisms to impose negative interest rates on physical cash, so as to make the escape route appear less attractive:

Last September, the Bank of England’s chief economist, Andy Haldane, openly pondered ways of imposing negative interest rates on cash — ie shrinking its value automatically. You could invalidate random banknotes, using their serial numbers. There are £63bn worth of notes in circulation in the UK: if you wanted to lop 1% off that, you could simply cancel half of all fivers without warning. A second solution would be to establish an exchange rate between paper money and the digital money in our bank accounts. A fiver deposited at the bank might buy you a £4.95 credit in your account.

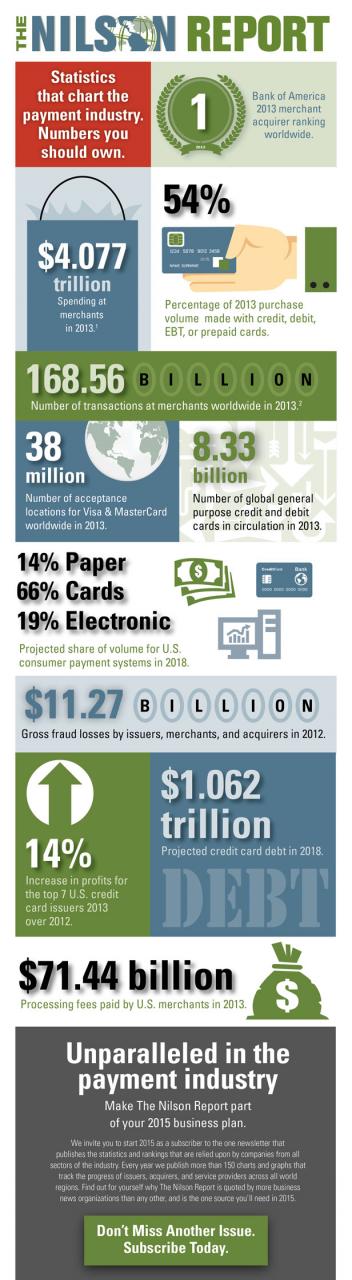

To put it mildly, invalidating random banknotes would be highly likely to result in significant social blowback, and to accelerate the evaporation of trust in governing authorities of all kinds. It would be far more likely for financial authorities to move toward making official electronic money the standard by which all else is measured. People are already used to using electronic money in the form of credit and debit cards and mobile phone money transfers:

I can remember the moment I realised the era of cash could soon be over. It was Australia Day on Bondi Beach in 2014. In a busy liquor store, a man wearing only swimming shorts, carrying only a mobile phone and a plastic card, was delaying other people’s transactions while he moved 50 Australian dollars into his current account on his phone so that he could buy beer. The 30-odd youngsters in the queue behind him barely murmured; they’d all been in the same predicament. I doubt there was a banknote or coin between them….The possibility of a cashless society has come at us with a rush: contactless payment is so new that the little ping the machine makes can still feel magical. But in some shops, especially those that cater for the young, a customer reaching for a banknote already produces an automatic frown. Among central bankers, that frown has become a scowl.

In some states almost anything, no matter how small, can be purchased electronically. Everything down to, and including, a cup of coffee from a roadside stall can be purchased in New Zealand with an EFTPOS (debit) card, hence relatively few people carry cash. In Scandinavian countries, there are typically more electronic payment options than cash options:

Sweden became the first country to enlist its own citizens as largely willing guinea pigs in a dystopian economic experiment: negative interest rates in a cashless society. As Credit Suisse reports, no matter where you go or what you want to purchase, you will find a small ubiquitous sign saying “Vi hanterar ej kontanter” (“We don’t accept cash”)….A similar situation is unfolding in Denmark, where nearly 40% of the paying demographic use MobilePay, a Danske Bank app that allows all payments to be completed via smartphone.

Even street vendors selling “Situation Stockholm”, the local version of the UK’s “Big Issue” are also able to take payments by debit or credit card.

Ironically, cashlessness is also becoming entrenched in some African countries. One might think that electronic payments would not be possible in poor and unstable subsistence societies, but mobile phones are actually very common in such places, and means for electronic payments are rapidly becoming the norm:

While Sweden and Denmark may be the two nations that are closest to banning cash outright, the most important testing ground for cashless economics is half a world away, in sub-Saharan Africa. In many African countries, going cashless is not merely a matter of basic convenience (as it is in Scandinavia); it is a matter of basic survival. Less than 30% of the population have bank accounts, and even fewer have credit cards. But almost everyone has a mobile phone. Now, thanks to the massive surge in uptake of mobile communications as well as the huge numbers of unbanked citizens, Africa has become the perfect place for the world’s biggest social experiment with cashless living.

Western NGOs and GOs (Government Organizations) are working hand-in-hand with banks, telecom companies and local authorities to replace cash with mobile money alternatives. The organizations involved include Citi Group, Mastercard, VISA, Vodafone, USAID, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

In Kenya the funds transferred by the biggest mobile money operator, M-Pesa (a division of Vodafone), account for more than 25% of the country’s GDP. In Africa’s most populous nation, Nigeria, the government launched a Mastercard-branded biometric national ID card, which also doubles up as a payment card. The “service” provides Mastercard with direct access to over 170 million potential customers, not to mention all their personal and biometric data. The company also recently won a government contract to design the Huduma Card, which will be used for paying State services. For Mastercard these partnerships with government are essential for achieving its lofty vision of creating a “world beyond cash.”

Countries where electronic payment is already the norm would be expected to be among the first places to experiment with a fully cashless society as the transition would be relatively painless (at least initially). In Norway two major banks no longer issue cash from branch offices, and recently the largest bank, DNB, publicly called for the abolition of cash. In rich countries, the advent of a cashless society could be spun in the media in such a way as to appear progressive, innovative, convenient and advantageous to ordinary people. In poor countries, people would have no choice in any case.

Testing and developing the methods in societies with no alternatives and then tantalizing the inhabitants of richer countries with more of the convenience to which they have become addicted is the clear path towards extending the reach of electronic payment systems and the much greater financial control over individuals that they offer:

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, in its 2015 annual letter, adds a new twist. The technologies are all in place; it’s just a question of getting us to use them so we can all benefit from a crimeless, privacy-free world. What better place to conduct a massive social experiment than sub-Saharan Africa, where NGOs and GOs (Government Organizations) are working hand-in-hand with banks and telecom companies to replace cash with mobile money alternatives? So the annual letter explains: “(B)ecause there is strong demand for banking among the poor, and because the poor can in fact be a profitable customer base, entrepreneurs in developing countries are doing exciting work – some of which will “trickle up” to developed countries over time.”

What the Foundation doesn’t mention is that it is heavily invested in many of Africa’s mobile-money initiatives and in 2010 teamed up with the World Bank to “improve financial data collection” among Africa’s poor. One also wonders whether Microsoft might one day benefit from the Foundation’s front-line role in mobile money….As a result of technological advances and generational priorities, cash’s days may well be numbered. But there is a whole world of difference between a natural death and euthanasia. It is now clear that an extremely powerful, albeit loose, alliance of governments, banks, central banks, start-ups, large corporations, and NGOs are determined to pull the plug on cash — not for our benefit, but for theirs.

Whatever the superficially attractive media spin, joint initiatives like the Better Than Cash Alliance serve their founders, not the public. This should not come as a surprise, but it probably will as we sleepwalk into giving up very important freedoms:

As I warned in We Are Sleepwalking Towards a Cashless Society, we (or at least the vast majority of people in the vast majority of countries) are willing to entrust government and financial institutions — organizations that have already betrayed just about every possible notion of trust — with complete control over our every single daily transaction. And all for the sake of a few minor gains in convenience. The price we pay will be what remains of our individual freedom and privacy.

Promoters, Mechanisms and Risks in the War on Cash

Bitcoin and other electronic platforms have paved the way psychologically for a shift away from cash, although they have done so by emphasising decentralisation and anonymity rather than the much greater central control which would be inherent in a mainstream electronic currency. The loss of privacy would no doubt be glossed over in any media campaign, as would the risks of cyber-attack and the lack of a fallback for providing liquidity to the economy in the event of a systems crash. Electronic currency is much favoured by techno-optimists, but not so much by those concerned about the risks of absolute structural dependency on technological complexity. The argument regarding greatly reduced socioeconomic resilience is particularly noteworthy, given the vulnerability and potential fragility of electronic systems.

There is an important distinction to be made between official electronic currency – allowing everyone to hold an account with the central bank — and private electronic currency. It would be official currency which would provide the central control sought by governments and central banks, but if individuals saw central bank accounts as less risky than commercial institutions, which seems highly likely, the extent of the potential funds transfer could crash the existing banking system, causing a bank run in a similar manner as large-scale cash withdrawals would. As the power of money creation is of the highest significance, and that power is currently in private hands, any attempt to threaten that power would almost certainly be met with considerable resistance from powerful parties. Private digital currency would be more compatible with the existing framework, but would not confer all of the control that governments would prefer:

People would convert a very large share of their current bank deposits into official digital money, in effect taking them out of the private banking system. Why might this be a problem? If it’s an acute rush for safety in a crisis, the risk is that private banks may not have enough reserves to honour all the withdrawals. But that is exactly the same risk as with physical cash: it’s often forgotten that it’s central bank reserves, not the much larger quantity of deposits, that banks can convert into cash with the central bank. Both with cash and official e-cash, the way to meet a more severe bank run is for the bank to borrow more reserves from the central bank, posting its various assets as security. In effect, this would mean the central bank taking over the funding of the broader economy in a panic — but that’s just what central banks should do.

A more chronic challenge is that people may prefer the safety of central bank accounts even in normal times. That would destroy private banks’ current deposit-funded model. Is that a bad thing? They would still have a role as direct intermediators between savers and borrowers, by offering investment products sufficiently attractive for people to get out of the safety of e-cash. Meanwhile, the broad money supply would be more directly under the control of the central bank, whereas now it’s a product of the vagaries of private lending decisions. The more of the broad money supply that was in the form of official digital cash, the easier it would be, for example, for the central bank to use tools such as negative interest rates or helicopter drops.

As an indication that the interests of the private banking system and public central authorities are not always aligned, consider the actions of the Bavarian Banking Association in attempting to avoid the imposition of negative interest rates on reserves held with the ECB:

German newspaper Der Spiegel reported yesterday that the Bavarian Banking Association has recommended that its member banks start stockpiling PHYSICAL CASH. The Bavarian Banking Association has had enough of this financial dictatorship. Their new recommendation is for all member banks to ditch the ECB and instead start keeping their excess reserves in physical cash, stored in their own bank vaults. This is officially an all-out revolution of the financial system where banks are now actively rebelling against the central bank. (What’s even more amazing is that this concept of traditional banking — holding physical cash in a bank vault — is now considered revolutionary and radical.)

There’s just one teensy tiny problem: there simply is not enough physical cash in the entire financial system to support even a tiny fraction of the demand. Total bank deposits exceed trillions of euros. Physical cash constitutes just a small percentage of that sum. So if German banks do start hoarding physical currency, there won’t be any left in the financial system. This will force the ECB to choose between two options:

- Support this rebellion and authorize the issuance of more physical cash; or

- Impose capital controls.

Given that just two weeks ago the President of the ECB spoke about the possibility of banning some higher denomination cash notes, it’s not hard to figure out what’s going to happen next.

Advantages of official electronic currency to governments and central banks are clear. All transactions are transparent, and all can be subject to fees and taxes. Central control over the money supply would be greatly increased and tax evasion would be difficult to impossible, at least for ordinary people. Capital controls would be built right into the system, and personal spending information would be conveniently gathered for inspection by central authorities (for cross-correlation with other personal data they possess). The first step would likely be to set up a dual system, with both cash and electronic money in parallel use, but with electronic money as the defined unit of value and cash subject to a marginally disadvantageous exchange rate.

The exchange rate devaluing cash in relation to electronic money could increase over time, in order to incentivize people to switch away from seeing physical cash as a store of value, and to increase their preference for goods over cash. In addition to providing an active incentive, the use of cash would probably be publicly disparaged as well as actively discouraged in many ways. For instance, key functions such as tax payments could be designated as by electronic remittance only. The point would be to forced everyone into the system by depriving them of the choice to opt out. Once all were captured, many forms of central control would be possible, including substantial account haircuts if central authorities deemed them necessary.

The main promoters of cash elimination in favour of electronic currency are Willem Buiter, Kenneth Rogoff, and Miles Kimball.

Economist Willem Buiter has been pushing for the relegation of cash, at least the removal of its status as official unit of account, since the financial crisis of 2008. He suggests a number of mechanisms for achieving the transition to electronic money, emphasising the need for the electronic currency to become the definitive unit of account in order to implement substantially negative interest rates:

The first method does away with currency completely. This has the additional benefit of inconveniencing the main users of currency-operators in the grey, black and outright criminal economies. Adequate substitutes for the legitimate uses of currency, on which positive or negative interest could be paid, are available. The second approach, proposed by Gesell, is to tax currency by making it subject to an expiration date. Currency would have to be “stamped” periodically by the Fed to keep it current. When done so, interest (positive or negative) is received or paid.

The third method ends the fixed exchange rate (set at one) between dollar deposits with the Fed (reserves) and dollar bills. There could be a currency reform first. All existing dollar bills and coin would be converted by a certain date and at a fixed exchange rate into a new currency called, say, the rallod. Reserves at the Fed would continue to be denominated in dollars. As long as the Federal Funds target rate is positive or zero, the Fed would maintain the fixed exchange rate between the dollar and the rallod.

When the Fed wants to set the Federal Funds target rate at minus five per cent, say, it would set the forward exchange rate between the dollar and the rallod, the number of dollars that have to be paid today to receive one rallod tomorrow, at five per cent below the spot exchange rate — the number of dollars paid today for one rallod delivered today. That way, the rate of return, expressed in a common unit, on dollar reserves is the same as on rallod currency.

For the dollar interest rate to remain the relevant one, the dollar has to remain the unit of account for setting prices and wages. This can be encouraged by the government continuing to denominate all of its contracts in dollars, including the invoicing and payment of taxes and benefits. Imposing the legal restriction that checkable deposits and other private means of payment cannot be denominated in rallod would help.

In justifying his proposals, he emphasises the importance of combatting criminal activity…

The only domestic beneficiaries from the existence of anonymity-providing currency are the criminal fraternity: those engaged in tax evasion and money laundering, and those wishing to store the proceeds from crime and the means to commit further crimes. Large denomination bank notes are an especially scandalous subsidy to criminal activity and to the grey and black economies.

… over the acknowledged risks of government intrusion in legitimately private affairs:

My good friend and colleague Charles Goodhart responded to an earlier proposal of mine that currency (negotiable bearer bonds with legal tender status) be abolished that this proposal was “appallingly illiberal”. I concur with him that anonymity/invisibility of the citizen vis-a-vis the state is often desirable, given the irrepressible tendency of the state to infringe on our fundamental rights and liberties and given the state’s ever-expanding capacity to do so (I am waiting for the US or UK government to contract Google to link all personal health information to all tax information, information on cross-border travel, social security information, census information, police records, credit records, and information on personal phone calls, internet use and internet shopping habits).

In his seminal 2014 paper “Costs and Benefits to Phasing Out Paper Currency.”, Kenneth Rogoff also argues strongly for the primacy of electronic currency and the elimination of physical cash as an escape route:

Paper currency has two very distinct properties that should draw our attention. First, it is precisely the existence of paper currency that makes it difficult for central banks to take policy interest rates much below zero, a limitation that seems to have become increasingly relevant during this century. As Blanchard et al. (2010) point out, today’s environment of low and stable inflation rates has drastically pushed down the general level of interest rates. The low overall level, combined with the zero bound, means that central banks cannot cut interest rates nearly as much as they might like in response to large deflationary shocks.

If all central bank liabilities were electronic, paying a negative interest on reserves (basically charging a fee) would be trivial. But as long as central banks stand ready to convert electronic deposits to zero-interest paper currency in unlimited amounts, it suddenly becomes very hard to push interest rates below levels of, say, -0.25 to -0.50 percent, certainly not on a sustained basis. Hoarding cash may be inconvenient and risky, but if rates become too negative, it becomes worth it.

However, he too notes associated risks:

Another argument for maintaining paper currency is that it pays to have a diversity of technologies and not to become overly dependent on an electronic grid that may one day turn out to be very vulnerable. Paper currency diversifies the transactions system and hardens it against cyber attack, EMP blasts, etc. This argument, however, seems increasingly less relevant because economies are so totally exposed to these problems anyway. With paper currency being so marginalized already in the legal economy in many countries, it is hard to see how it could be brought back quickly, particularly if ATM machines were compromised at the same time as other electronic systems.

A different type of argument against eliminating currency relates to civil liberties. In a world where society’s mores and customs evolve, it is important to tolerate experimentation at the fringes. This is potentially a very important argument, though the problem might be mitigated if controls are placed on the government’s use of information (as is done say with tax information), and the problem might also be ameliorated if small bills continue to circulate. Last but not least, if any country attempts to unilaterally reduce the use of its currency, there is a risk that another country’s currency would be used within domestic borders.

Miles Kimball’s proposals are very much in tune with Buiter and Rogoff:

There are two key parts to Miles Kimball’s solution. The first part is to make electronic money or deposits the sole unit of account. Everything else would be priced in terms of electronic dollars, including paper dollars. The second part is that the fixed exchange rate that now exists between deposits and paper dollars would become variable. This crawling peg between deposits and paper currency would be based on the state of the economy. When the economy was in a slump and the central bank needed to set negative interest rates to restore full employment, the peg would adjust so that paper currency would lose value relative to electronic money. This would prevent folks from rushing to paper currency as interest rates turned negative. Once the economy started improving, the crawling peg would start adjusting toward parity.

This approach views the economy in very mechanistic terms, as if it were a machine where pulling a lever would have a predictable linear effect — make holding savings less attractive and automatically consumption will increase. This is actually a highly simplistic view, resting on the notions of stabilising negative feedback and bringing an economy ‘back into equilibrium’. If it were so simple to control an economy centrally, there would never have been deflationary spirals or economic depressions in the past.

Assuming away the more complex aspects of human behaviour — a flight to safety, the compulsion to save for a rainy day when conditions are unstable, or the natural response to a negative ‘wealth effect’ — leads to a model divorced from reality. Taxing savings does not necessarily lead to increased consumption, in fact it is far more likely to have the opposite effect.:

But under Miles Kimball’s proposal, the Fed would lower interest rates to below zero by taxing away balances of e-currency. This is a reduction in monetary base, just like the case of IOR, and by itself would be contractionary, not expansionary. The expansionary effects of Kimball’s policy depend on the assumption that households will increase consumption in response to the taxing of their cash savings, rather than letting their savings depreciate.

That needn’t be the case — it depends on the relative magnitudes of income and substitution effects for real money balances. The substitution effect is what Kimball has in mind — raising the price of real money balances will induce substitution out of money and into consumption. But there’s also an income effect, whereby the loss of wealth induces less consumption and more savings. Thus, negative interest rate policy can be contractionary even though positive interest rate policy is expansionary.

Indeed, what Kimball has proposed amounts to a reverse Bernanke Helicopter — imagine a giant vacuum flying around the country sucking money out of people’s pockets. Why would we assume that this would be inflationary?

Given that the effect on the money supply would be contractionary, the supposed stimulus effect on the velocity of money (as, in theory, savings turn into consumption in order to avoid the negative interest rate penalty) would have to be large enough to outweigh a contracting money supply. In some ways, modern proponents of electronic money bearing negative interest rates are attempting to copy Silvio Gesell’s early 20th century work. Gesell proposed the use of stamp scrip — money that had to be regularly stamped, at a small cost, in order to remain current. The effect would be for money to lose value over time, so that hoarding currency it would make little sense. Consumption would, in theory, be favoured, so money would be kept in circulation.

This idea was implemented to great effect in the Austrian town of Wörgl during the Great Depression, where the velocity of money increased sufficiently to allow a hive of economic activity to develop (temporarily) in the previously depressed town. Despite the similarities between current proposals and Gesell’s model applied in Wörgl, there are fundamental differences:

There is a critical difference, however, between the Wörgl currency and the modern-day central bankers’ negative interest scheme. The Wörgl government first issued its new “free money,” getting it into the local economy and increasing purchasing power, before taxing a portion of it back. And the proceeds of the stamp tax went to the city, to be used for the benefit of the taxpayers….Today’s central bankers are proposing to tax existing money, diminishing spending power without first building it up. And the interest will go to private bankers, not to the local government.

The Wörgl experiment was a profoundly local initiative, instigated at the local government level by the mayor. In contrast, modern proposals for negative interest rates would operate at a much larger scale and would be imposed on the population in accordance with the interests of those at the top of the financial foodchain. Instead of being introduced for the direct benefit of those who pay, as stamp scrip was in Wörgl, it would tax the people in the economic periphery for the continued benefit of the financial centre. As such it would amount to just another attempt to perpetuate the current system, and to do so at a scale far beyond the trust horizon.

As the trust horizon contracts in times of economic crisis, effective organizational scale will also contract, leaving large organizations (both public and private) as stranded assets from a trust perspective, and therefore lacking in political legitimacy. Large scale, top down solutions will be very difficult to implement. It is not unusual for the actions of central authorities to have the opposite of the desired effect under such circumstances:

Consumers today already have very little discretionary money. Imposing negative interest without first adding new money into the economy means they will have even less money to spend. This would be more likely to prompt them to save their scarce funds than to go on a shopping spree. People are not keeping their money in the bank today for the interest (which is already nearly non-existent). It is for the convenience of writing checks, issuing bank cards, and storing their money in a “safe” place. They would no doubt be willing to pay a modest negative interest for that convenience; but if the fee got too high, they might pull their money out and save it elsewhere. The fee itself, however, would not drive them to buy things they did not otherwise need.

People would be very likely to respond to negative interest rates by self-organising alternative means of exchange, rather than bowing to the imposition of negative rates. Bitcoin and other crypto-currencies would be one possibility, as would using foreign currency, using trading goods as units of value, or developing local alternative currencies along the lines of the Wörgl model:

The use of sheep, bottled water, and cigarettes as media of exchange in Iraqi rural villages after the US invasion and collapse of the dinar is one recent example. Another example was Argentina after the collapse of the peso, when grain contracts priced in dollars were regularly exchanged for big-ticket items like automobiles, trucks, and farm equipment. In fact, Argentine farmers began hoarding grain in silos to substitute for holding cash balances in the form of depreciating pesos.