DPC Snow removal – Ford tractor Washington, DC 1925

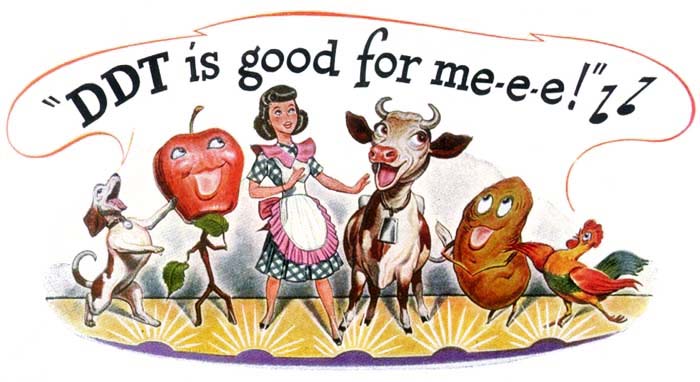

Good piece on derivatives. I’m always suspicious of claims that outstanding contracts are down $150 trillion or so. Derivatives, and certainly swaps, are a great way to hide risks and losses. Why let go of that? Who can even afford to do it?

• Banks’ Balance Sheets Are Poor Guides To Actual Risks And Uncertainties (FT)

According to the latest data from the Bank for International Settlements, the central bankers’ central bank, the total amount of outstanding derivative contracts has declined from a 2012 peak of $700tn to about $550tn. To put this into perspective, the figure has fallen from just under three times the value of all the assets in the world to a little over twice the value. The largest element is interest rate swaps followed by foreign exchange derivatives. Credit default swaps, the instrument at the heart of the 2008 global financial crisis, are now relatively small – if you can accustom yourself to a world in which $15tn is a small number. It is only slightly less than US GDP (a little more than $18tn in the final quarter of 2015). Two banks, JPMorgan and Deutsche Bank, account for about 20% of total global derivatives exposure.

Each has more than $50tn potentially at risk. The current market capitalisation of JP Morgan is about $200bn (roughly its book value); that of Deutsche, $23bn (about one third of book value). From one perspective, Deutsche Bank is leveraged 2,000 times. Imagine promising to buy a house for $2,000 with assets of $1. Before you head for the hills, or the bunker, understand that there is no possibility that these banks could actually lose $50tn. The risks associated with these exposures are largely netted out — that is, they offset each other. As you promised to buy the house in question, you also promised to sell it: though not necessarily at just the same time or price or to the same person. That mismatch is the source of potential profit. How effectively are these positions netted? Your guess is as good as mine, and probably not much worse than those in charge of these institutions.

We are reliant on their risk modelling but these models break down in precisely the extreme situations they are designed to protect us against. You will not find these figures for derivative exposures in the balance sheets of banks nor do such exposures enter directly into capital adequacy calculations. The apparent lack of impact on balance sheet totals is the product of the combination of fair value accounting and the tradition of judging the security of a bank by the size of its credit exposure (counterparty risk) rather than its economic exposure (loss from market fluctuation). The fair value today of an agreement that has an equal chance of you paying me £100 or me paying you £100 is zero. Since your promise to pay or receive £100 is marked to market at nil there is no credit risk: you cannot default on a liability to pay nothing.

Under generally accepted accounting principles in the US, you are allowed even to net out exposures to the same counter party in declaring your derivative position. This is not permitted under international financial reporting standards, which is why the balance sheets of American banks appear (misleadingly) to be smaller than those of similar European institutions. The fundamental problem is accounting at “fair value” when that fair value is the average of a wide range of possible outcomes. The mean of a distribution may itself be an impossible occurrence — there are no families with 1.8 children, for example. And netting offsetting positions may also mislead. There is a large difference between being a dollar millionaire and having assets of $100m and liabilities of $99m.

Read more …

“..a vital consideration, particularly in the US market, is that Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio is at levels substantially exceeded only in the stock market bubbles that peaked in 1929 and 2000..”

• Banks Are Still The Weak Links In The Economic Chain (FT)

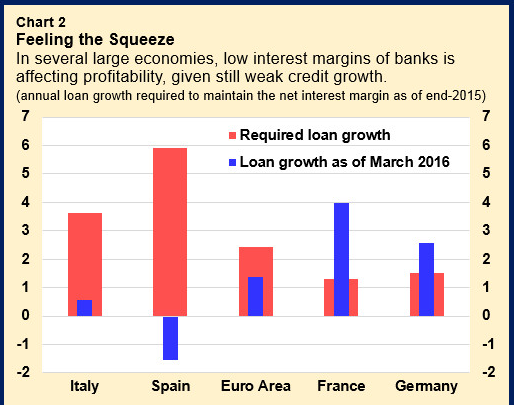

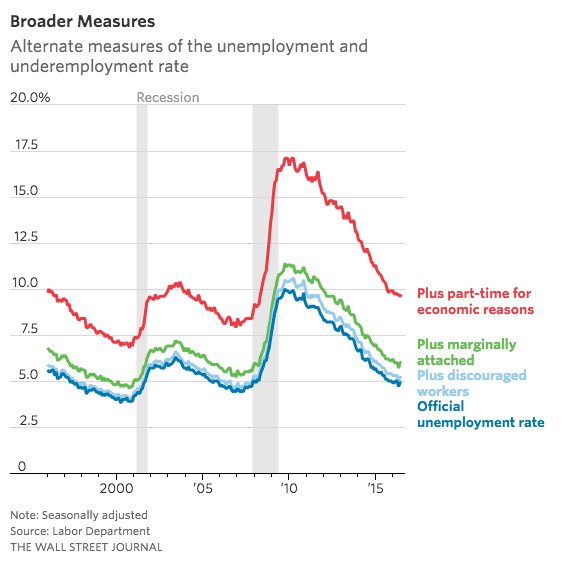

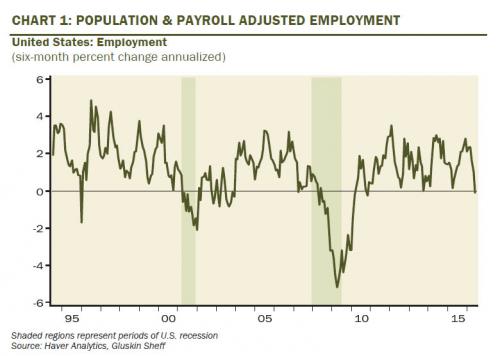

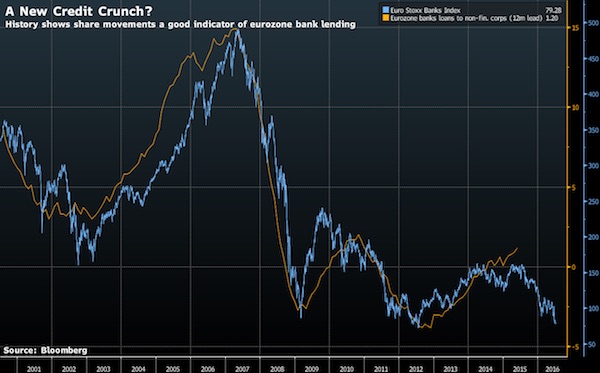

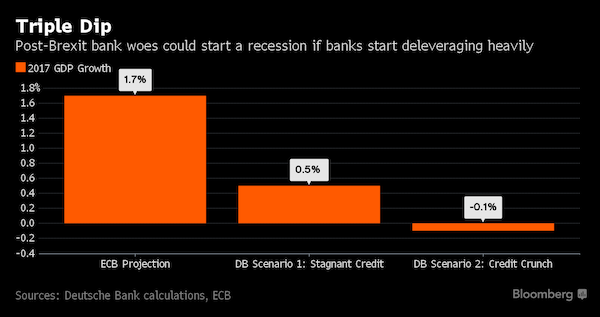

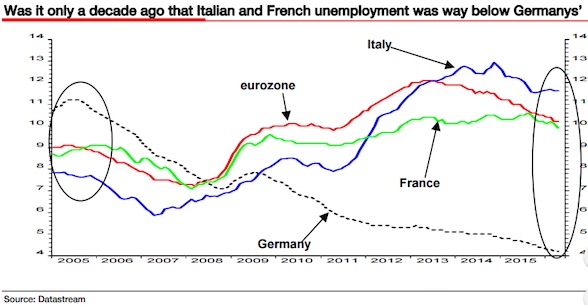

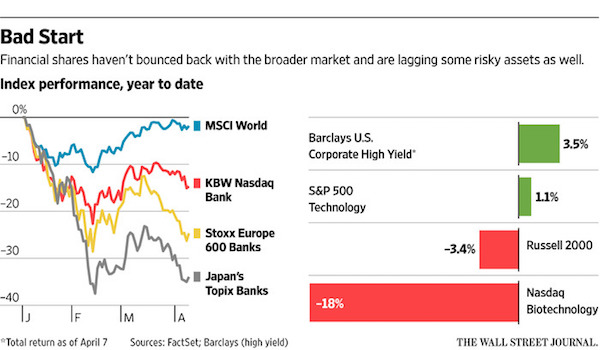

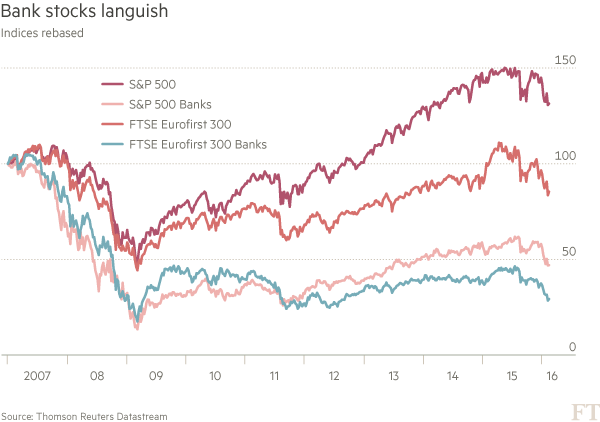

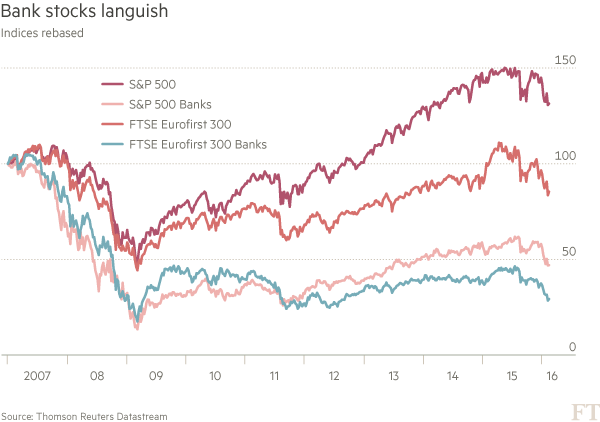

Why have the prices of bank shares fallen so sharply? A part of the answer is that stock markets have declined. Banks, however, remain the weak link in the chain, fragile themselves and able to generate fragility around them. Between January 4 and February 15 2016, the Standard & Poor 500 index fell 7.5% while the index of bank stocks fell 16.1%. Over the same period, the FTSE Eurofirst 300 fell 9.5%, while the index of bank stocks fell 19.5%. The decline of European stocks was a little bigger than that of US ones but the underperformance of the European banking sector was similar. Relative to the overall US market, the index of shares in US banks fell 9.1%, while that of European banks fell 11% relative to European markets — and so only a bit more. The dire performance of European banks becomes more evident if one takes a longer view.

Bank stocks have failed to recover the huge losses they suffered in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007-09. On February 15 2015, the S&P 500 was 23% higher than on July 2 2007 but the US banking sector was still 51% below where it had been then; the FTSE Eurofirst was 21% below its 2007 level, reflecting the botched European recovery, but its banking sector was down by 71%. In the European case a decline of 40% in the value of bank stocks would return them to the 2009 nadir. So what might explain what is going on? The short answer is always: who knows? Mr Market is subject to huge mood swings. Yet a vital consideration, particularly in the US market, is that Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio is at levels substantially exceeded only in the stock market bubbles that peaked in 1929 and 2000. Investors might simply have realised that the downside risks to stocks outweigh the upside possibilities. Plausible worries could also have triggered such a realisation. Of such worries, there is no lack.

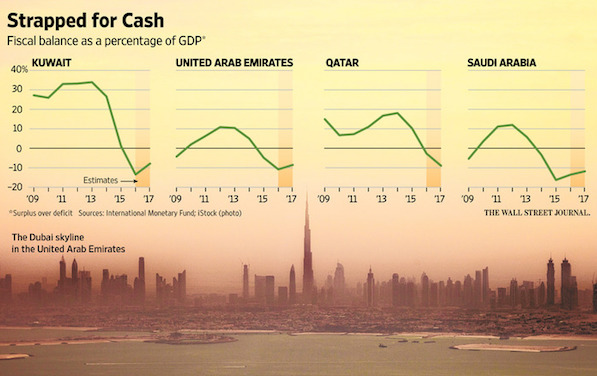

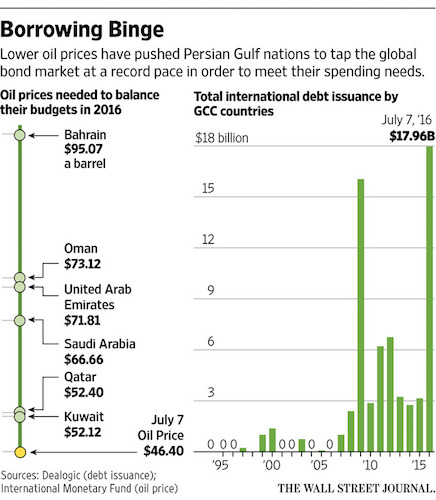

One might be anxious about a slowdown in the American economy, partly driven by the strong dollar, weakening corporate profits and a misguided commitment to tightening by the US Federal Reserve. One might fear the short-term damage being done by collapsing commodity prices, which are imposing economic and fiscal stresses on commodity-exporting countries and financial pressures on commodity-producing companies. One might be concerned over the need for sovereign wealth funds to liquidate assets to fund fiscally stressed governments, particularly of the oil exporters. One might worry about a big slowdown in China and the ineffectiveness of its government’s policies. One might fear a new crisis in the eurozone. One might be worried about geopolitical risks, including the threat of war between Russia and Nato, disintegration of the EU and the chance that the next US president will be a hardline populist.

Read more …

And that crisis is inevitable.

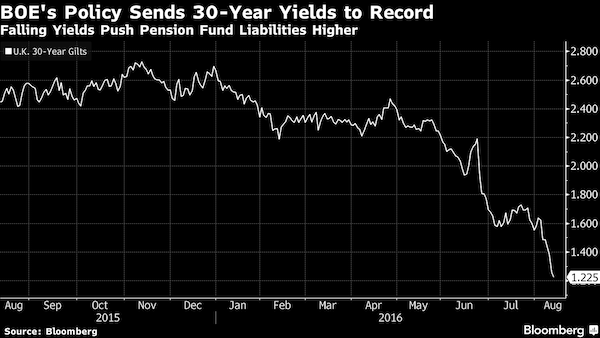

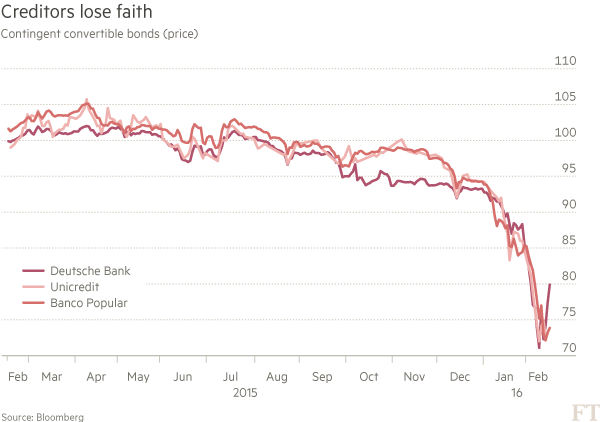

• The Eurozone Can’t Survive Another Banking Crisis (MW)

In the end, it was not quite another 2008. There were no queues around the block in Hanover or Dusseldorf as people tried to withdraw their life savings from the bank, and there was no Lehman moment where angry and bewildered looking bankers were turfed out onto the streets of Frankfurt. Even so, the wobble in the German banking system over the last week, centered in particular over the stability of the mighty Deutsche Bank, was still a troubling moment for the eurozone. Why? Because it now looks like the single currency would find it very hard to survive another banking crisis. That is not because the central bank would not step up to the plate. There can be no question that Mario Draghi would print all the euros needed to bail out the banks if he had to. It is because the politics would make it impossible.

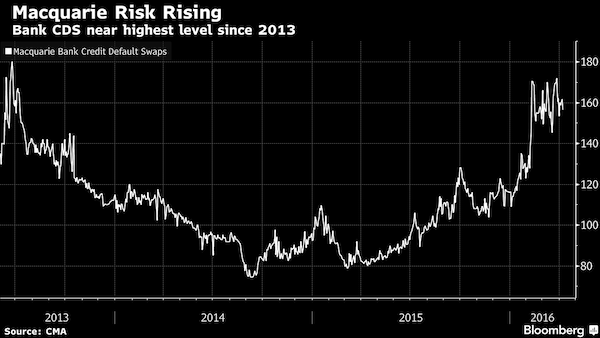

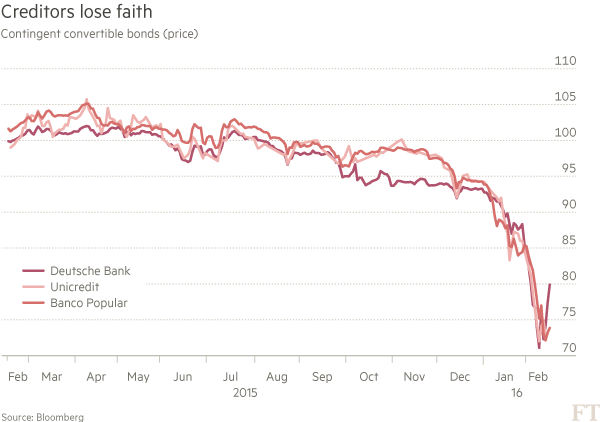

The Greek banks were allowed to close for a long period last year, and capital controls were introduced, so if the ECB were to fully rescue French and German banks while it placed restrictions on Greek ones, the contrast would become too painful to ignore. If any banks go down, they will take the euro with them. This has certainly been a bad month to be a shareholder in Deutsche Bank, or indeed any of the major eurozone lenders. Last week, shares in Deutsche fell off a cliff. From more than €20 last month, they slumped all the way down to slightly more than €13. The prices of its convertible bonds sank to an all-time low, and the cost of its credit default swaps soared, as at least some people in the market seemed to want to make a bet against its survival.

The situation became so bad that at one point its chief executive John Cryan was wheeled out to reassure everyone the bank was “rock solid,” the kind of statement that could have been purposefully designed to put everyone on edge. The carnage was even worse in the Italian banking system, always fragile at the best of times, and by the close of the week started to spread to France as well. It was not quite 2008 all over again, but it was also too close to it for comfort. The reasons for the nervousness were not hard to work out. The one thing we learned in 2008 is that the financial system is interconnected, and that losses in one market can easily turn up somewhere else. Oil and commodity prices have slumped across the world, and it would be surprising if at least some of those losses were not showing up in the banking system somewhere.

Read more …

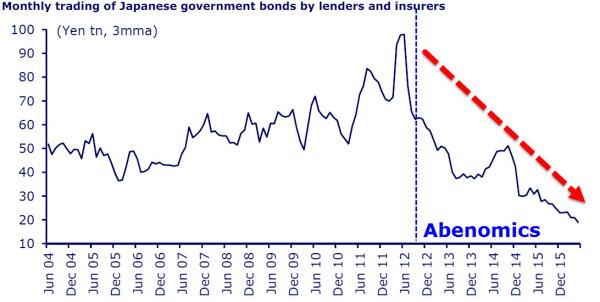

“The decline in exports is particularly troubling for Abenomics. It never cared about consumers. To heck with them. It’s all about exports and Japan Inc. ”

• I’m in Awe at Just How Fast Global Trade is Unraveling (WS)

It simply doesn’t let up. Global trade is skidding south at a breath-taking speed. China produced a doozie: The General Administration of Customs reported on Monday that in yuan terms, exports dropped 6.6% in January from a year ago while imports plunged 14.4%. In dollar terms, it was even worse due to the depreciation of the yuan since August: exports plunged 11.2% and imports 18.8%, far worse than economists had expected. And so the trade surplus, powered by those plunging imports, jumped 12.2% to a record $63.3 billion. This came on top of China’s deteriorating trade numbers last year, when exports had fallen 1.8% in yuan terms while imports had plunged 13.2%. Imports have now declined for 15 months in a row. That’s tough for the world economy.

OK, Chinese trade data can be heavily distorted by fake invoicing of “imports” from Hong Kong, a practice used to maneuver around capital controls and send money out of China. Imports from Hong Kong in January soared 108% from a year ago, even as shipments from other major trading partners declined. Bloomberg: “China has acknowledged a problem with fake invoicing in the past. In 2013, the government said export and import figures were overstated due to the phony trade to bring money into the mainland. Trade data for December suggested the practice had flared up again, this time to get money out.” In January, we have the additional fudge factor of the Lunar New Year. Chinese companies were closed all last week. It caused all kinds of front-loading in December and early January followed by a wind-down in late January and early February.

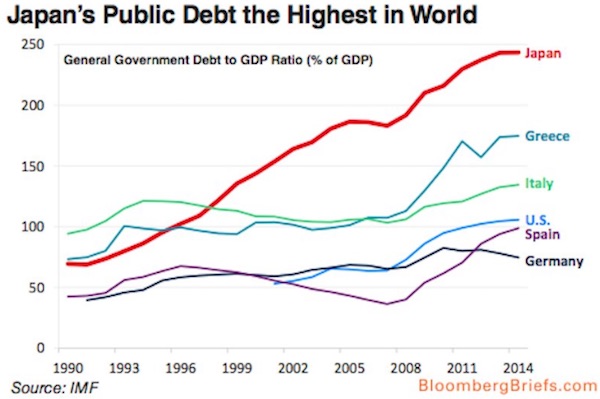

Oh, and India: “On Monday, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry in Asia’s third largest economy reported that exports of goods plunged 13.6% in January year-over-year, the 14th month in a row of declines. To blame are crummy global demand, including in the US and Europe, and as always a weaker currency somewhere, this time in China. And Japan. The economy shrank in the October through December quarter, the second quarterly decline so far this fiscal year, which started April 1. Over the past nine quarters, five booked declines; over the past 20 quarters, 10 showed declines. Most sectors got hit: consumption, housing investment, exports…. The decline in exports is particularly troubling for Abenomics. It never cared about consumers. To heck with them. It’s all about exports and Japan Inc.

But two weeks ago, the Ministry of Finance reported that in December exports had dropped 8% year over year while imports had plunged 18%. In the first half of 2015, exports still rose 7.9%; but in the second half, they declined 0.6%. Turns out, the bottom fell out during the last three months of the year: exports dropped 2.2% in October, 3.3% in November, and 8.0% in December. In December, exports to the rest of Asia plunged 10.3%! Within that, exports to China plunged 8.6%. Asia is Japan’s largest export market by far, accounting for over 52% of total exports and dwarfing exports to the US and Canada, at 23% of total exports.

Read more …

Not only is he a great guy to hang out with, everything Steve writes is must read because he corrects so many fallacies spread by economists and media.

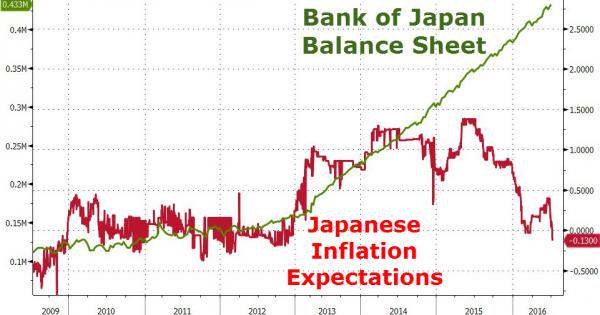

• Tilting At Windmills: The Faustian Folly Of Quantitative Easing (Steve Keen)

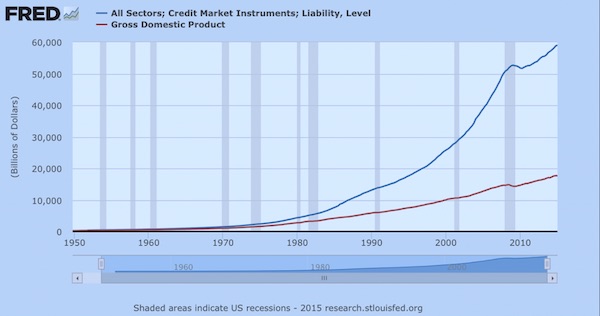

As I explained in my last post, banks can’t “lend out reserves” under any circumstances, which undermines a major rationale that Central Bank economists gave for undertaking Quantitative Easing in the first place. Consequently, the hope that Bernanke expressed in 2009 is “To Dream The Impossible Dream”:

To dream the impossible dream

To fight the unbeatable foe

To bear with unbearable sorrow

To run where the brave dare not go

But without the poetry: Large increases in bank reserves brought about through central bank loans or purchases of securities are a characteristic feature of the unconventional policy approach known as quantitative easing. The idea behind quantitative easing is to provide banks with substantial excess liquidity in the hope that they will choose to use some part of that liquidity to make loans or buy other assets. (Bernanke 2009, “The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet: An Update”)

What a folly this was—almost. The one out that Bernanke gives himself from pure delusional babble is the phrase “or buy other assets”—because that’s the one thing that banks can actually do with the excess reserves that QE has generated. But rather than rescuing Central Bankers from folly, this escape clause is an unwitting pact with the devil: they are now caught in a Faustian bargain. Any attempt to terminate QE is likely to end in deflating the asset markets that it inflated in the first place, which will cause the Central Banks to once more come “riding to the rescue” on their monetary Rocinante.

While Central Bankers can personally still join Faust and ascend to Heaven—thanks to their comfortable public salaries and pensions—the rest of us have been thrust into the Hell of expanding and bursting speculative bubbles, hoist on the ill-designed lance of QE. Bernanke is a rich man’s incompetent Frank N. Furter: confronting a wet and shivering couple, he promises to remove the cause—but not the symptom:

So, come up to the lab,/ and see what’s on the slab!/ I see you shiver with antici… …pation./ But maybe the rain/ isn’t really to blame,/ so I’ll remove the cause…/ [chuckles] but not the symptom. (“Sweet Transvestite”)

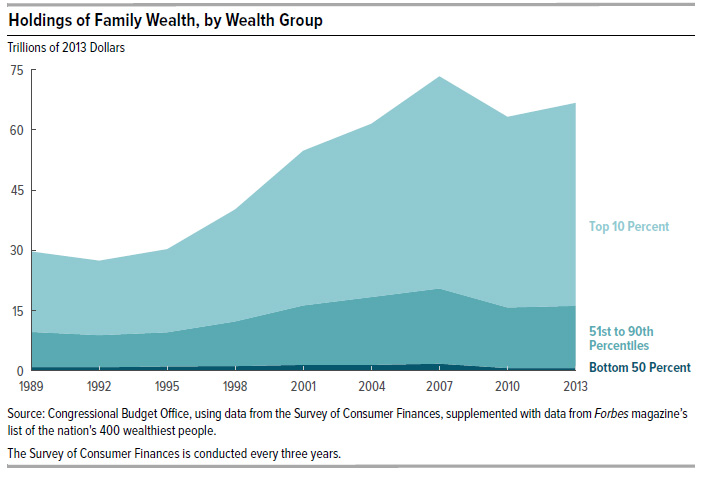

Bernanke’s QE instead maintains the symptoms of the crisis, but does nothing about its cause. It generates rampant inequality, drives asset prices sky-high and causes frequent financial panics—while doing nothing to reduce the far too high a level of private debt that caused the crisis. Let’s put QE on the slab in my lab—my Minsky software—and track the logic of the monetary flows that QE can trigger.

Read more …

Crush depth is a great metaphor.

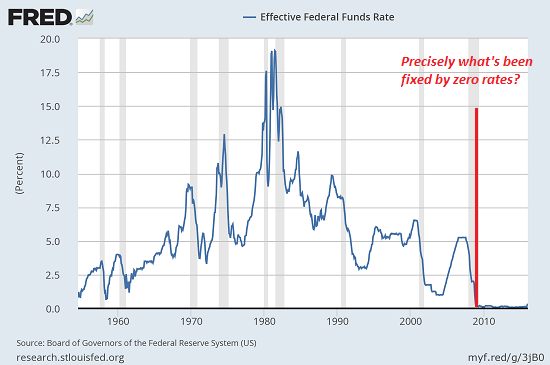

• If Zero Interest Rates Fixed What’s Broken, We’d Be in Paradise (CHS)

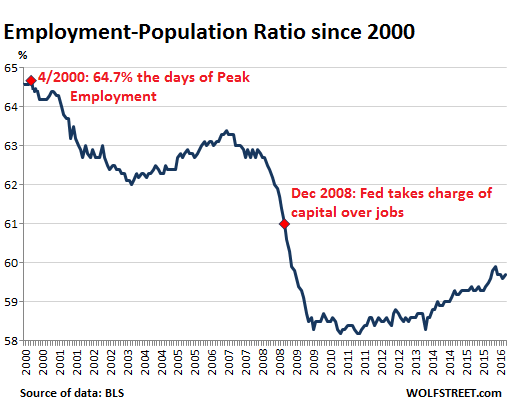

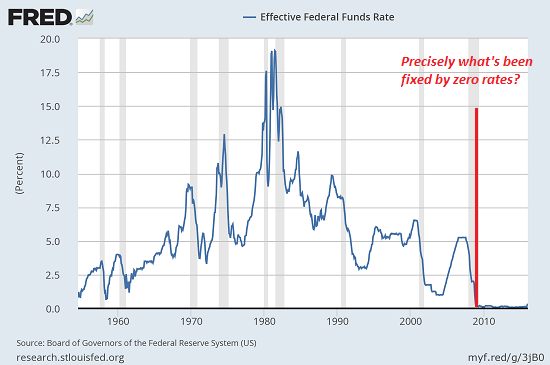

Rather than fix what’s broken with the real economy, ZIRP/NIRP has added problems that only collapse can solve. The fundamental premise of global central bank policy is simple: whatever’s broken in the economy can be fixed with zero interest rates (ZIRP). And the linear extension of this premise is equally simple: if ZIRP hasn’t fixed what’s broken, then negative interest rates (NIRP) will. Unfortunately, this simplistic policy has run aground on the shoals of reality: if zero or negative interest rates actually fixed what’s broken in the economy, we’d all be living in Paradise after seven years of zero interest rates. The truth that cannot be spoken is that zero interest rates (ZIRP) and negative interest rates (NIRP) cannot fix what’s broken–rather, they have added monumental quantities of risk that have dragged the global financial system down to crush depth:

“Crush depth, officially called collapse depth, is the submerged depth at which a submarine’s hull will collapse due to pressure. This is normally calculated; however, it is not always accurate.” Indeed, the risk that has been generated by ZIRP and NIRP cannot be calculated with any accuracy. The sources of risk arising from NIRP are well-known:

1. Zero interest rates force investors and money managers to chase yield, i.e. seek a positive return on their capital. In a world dominated by central bank ZIRP/NIRP, this requires taking on higher risk, as higher yields are a direct consequence of higher risk. The problem is that the risk and the higher yield are asymmetric: to earn a 4% return, investors could be taking on risks an order of magnitude higher than the yield.

2. To generate fees in a ZIRP/NIRP world, lenders must loan vast sums to marginal borrowers–borrowers who would not qualify for loans in more prudent times. This forces lenders to either forego income from lending or take on enormous risks in lending to marginal borrowers.

3. The income once earned by conventional savers has been completely destroyed by ZIRP/NIRP, depriving the economy of a key income stream. Please consider this chart of the Fed Funds Rate and tell me precisely what’s been fixed by seven years of zero interest rates:

Read more …

There’s a few screws loose, alright.

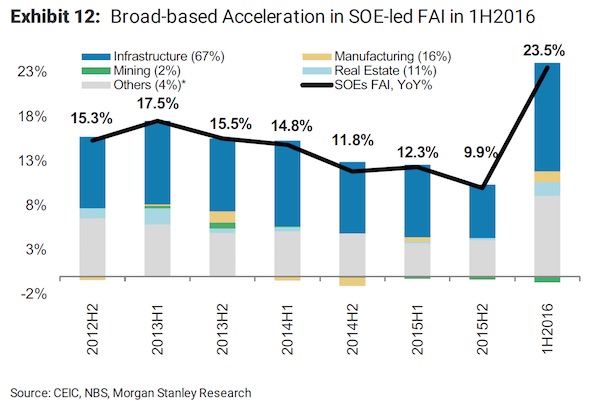

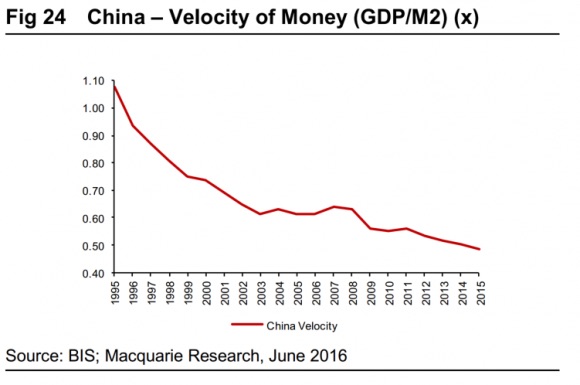

• China Turns on Taps and Loosens Screws in Bid to Support Growth (BBG)

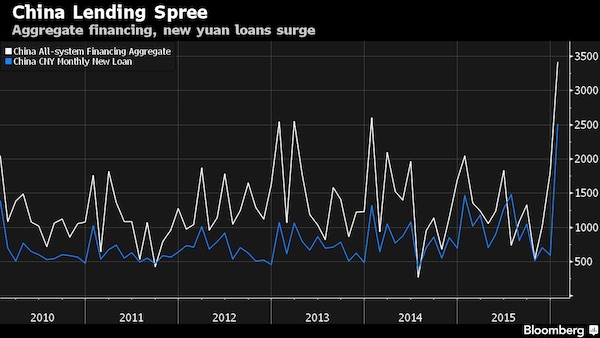

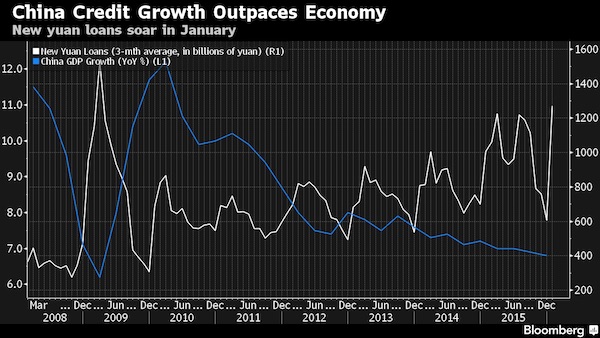

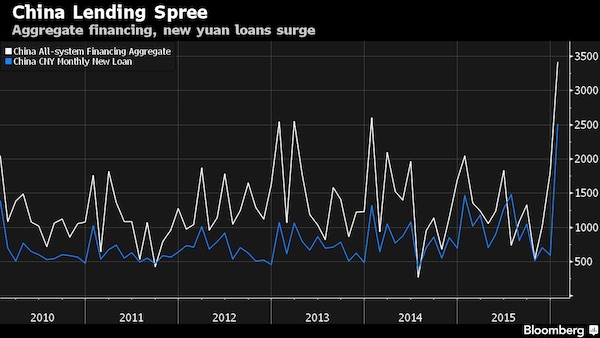

China is stepping up support for the economy by ramping up spending and considering new measures to boost bank lending. The nation’s chief planning agency is making more money available to local governments to fund new infrastructure projects, according to people familiar with the matter. Meantime, China’s cabinet has discussed lowering the minimum ratio of provisions that banks must set aside for bad loans, a move that would free up additional cash for lending. Officials are upping their rhetoric too. Premier Li Keqiang said policy makers “still have a lot of tools in the box” to combat the slowdown in the world’s No. 2 economy, days after People’s Bank of China Governor Zhou Xiaochuan broke a long silence to talk up confidence in the nation’s currency, the yuan.

And to ram the message home, the biggest economic planning agencies on Tuesday promised to reduce financing costs as they rein in overcapacity. Throw in a record surge in lending in January and a picture emerges of an administration determined to put a floor under growth. “Policymakers are battling to prevent any further slowdown, which could escalate into a hard landing,” said Rajiv Biswas at IHS Global Insight in Singapore. “These additional measures will act to boost liquidity in the banking sector and increase local government spending on infrastructure development.”

Read more …

They’ll just start their own ratings agency.

• China Debt Binge Spurs S&P Warning (BBG)

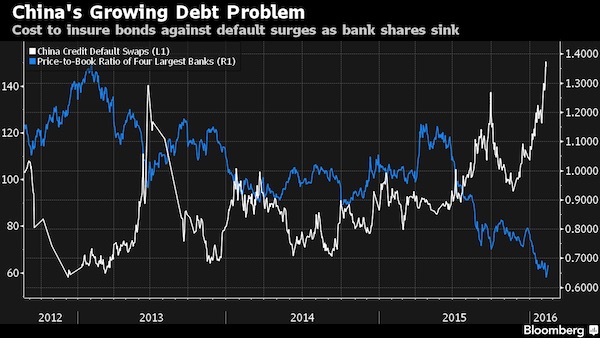

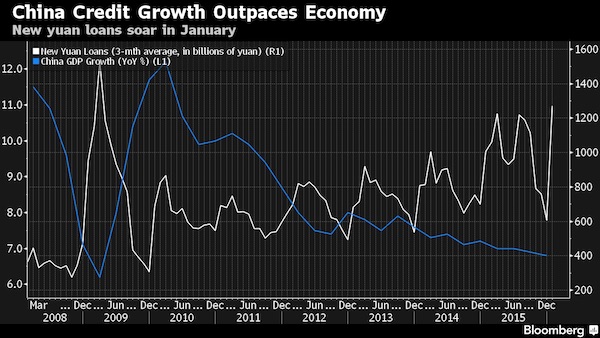

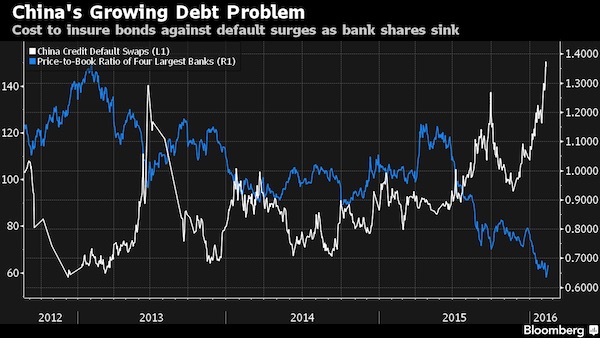

China’s unprecedented jump in new loans at the start of 2016 is fueling concern that excessive credit growth is piling up risks in the nation’s financial system. The increase in China’s debt relative to gross domestic product could pressure the country’s credit rating, Standard & Poor’s said on Tuesday, less than a week after the cost to insure Chinese bonds against default rose to a four-year high. Credit growth is storing up “big problems” in the economy that will weigh on the yuan and stocks, said George Magnus, an economic adviser to UBS. Mizuho Bank. warned that the threat of bad loans is rising and Marketfield Asset Management said China’s central bank may be losing its regulatory grip on credit growth.

While part of January’s surge in new debt to a record 3.42 trillion yuan ($525 billion) was caused by seasonal factors and a switch into local-currency liabilities from overseas borrowings, the risk is that bad debts will jump as companies find fewer profitable projects amid the slowest economic expansion in a quarter century. Soured loans at Chinese commercial banks rose to the highest level since June 2006 at the end of last year and the country’s biggest lenders trade at a 33% discount to net assets in the stock market — a sign that investors see further writedowns to banks’ loan books. The jump in credit growth “may help to sustain the pace of economic momentum in the short term, but it’s storing up big problems,” said Magnus, who correctly predicted in July that the rout in Chinese stocks would deepen.

“I’m not anticipating an imminent meltdown, but we’ve got a lot of warnings going on that should make us cautious about how we see the situation developing for the course of this year.” China’s ratio of corporate and household borrowing versus gross domestic product rose to 209% at the end of 2015, the highest level since Bloomberg Intelligence began compiling the data in 2003. Nonperforming loans increased 7% in the fourth quarter to 1.27 trillion yuan, data from the China Banking Regulatory Commission showed Monday.

“While corporate financial risks are not as high as what the leverage level suggests – as companies tend to hold a lot of liquid assets – the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio still poses a systemic risk, which could potentially add pressure to ratings,” Kim Eng Tan at S&P said in an interview in Shanghai.

[..] “Although the government and other senior officials do talk about deleveraging and slowing credit creation, a lot of it is talk,” Magnus said. “We don’t see very much in the way of concrete actions to try to limit the amount of new credit going into the economy.” Marketfield Asset’s Michael Shaoul said the PBOC’s ability to prevent excessive credit growth may be waning as the country loosens regulatory control over the financial system. “How much of this is a result of deliberate policy rather than extreme moves made by the private sector is open to argument,” Shaoul said. “We increasingly suspect that the PBOC has lost substantial control of the events we are witnessing, with both the partial deregulation of financial markets and multiple conflicting policy aims making regulatory control increasingly difficult without massive unintended consequences.”

Read more …

They never had that control, but never understood that either.

• China Loses Control of the Economic Story Line (WSJ)

Sentiment on China among global investors has always veered between exaggerated optimism and excessive pessimism. Even so, the latest bout of gloom is unusually severe. The economic slowdown doesn’t properly explain it. Although the official 6.9% growth last year was the slowest in a quarter century—and many economists believe the real number is more like 6%–China is still expanding faster than almost any other major economy. Banks are flush with savings. The government retains plenty of financial firepower. Unemployment is low. The reason for the startling mood swing this time goes well beyond the performance of the economy. It’s fundamentally about leadership—how the world’s second-largest economy is run.

When President Xi Jinping rose to power in 2012, investors knew the economy was ailing—“unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable,” as former Premier Wen Jiabao famously described it in 2007. His blunt diagnosis of China’s broken growth model was also a kind of confessional; Mr. Wen, together with President Hu Jintao, recognized the problems early but made them much worse with wasteful government investment in heavy industry and infrastructure. Mr. Xi pledged to do vastly better. Styling himself as a reformer on a par with Deng Xiaoping, he unveiled a 60-point plan to roll back the state and cede a “decisive role” to markets as China set out to switch from investment to consumption-led growth. Yet entering year four—out of an expected 10—of Mr. Xi’s administration, the reforms are largely on hold.

Capital flooding out of China is one sign that some investors are giving up the wait. Today’s disillusion is focused largely on China’s future prospects, not its current condition. Absent the reassurance of reform progress, the expectation is that growth will stall. Only the timing is in doubt. Why the delay? Some say Mr. Xi has been too busy consolidating his power, or that he’s been consumed by his anticorruption campaign. It takes time, they point out, to build consensus on controversial overhauls to rejuvenate state-owned enterprises, open the financial system to greater competition and liberalize land and labor markets.But evidence is building that reforms have stalled for a more basic reason: Mr. Xi, despite the early hype, sees only a limited role for markets.

Read more …

“They’re so overexposed in Venezuela.”

• China’s Big Bet On Latin America Is Going Bust (CNN)

China is pumping billions into Latin America, but many of its investments are tanking. Last year alone, China offered $65 billion to Latin America, it biggest bet yet. Many see the move as a power play to counter the U.S. influence in the region. Perhaps the best example of China’s growing ambitions – and problems – in the region is its plan to construct a railroad stretching 3,300 miles from Brazil’s Atlantic coast to Peru’s Pacific Coast. It’s a massive area that’s equivalent to the distance between Miami and Seattle. The Chinese government is used to implementing its vision quickly at home. Latin America moves much slower. The railroad project is fraught with challenges, such as dealing with indigenous groups and environmental concerns, not to mention the sheer scale of laying that much track.

China has tried – and failed – with this game plan before. China had “quite advanced” plans in 2011 for a railway connecting connecting Colombia’s Pacific and Atlantic coasts, according to an interview Colombia’s President Juan Manuel Santos gave the FT that year. Five years later, no such railway exists. It isn’t even under construction. This smaller railroad would be one of China’s most explicit power plays against the United States, creating direct competition with the Panama Canal. Colombia should have been easy to work with. It is one of the best-performing economies in Latin America, and it’s politically stable. “Culturally, we are very different and sometimes it stops the projects,” says Julian Salamanca, executive director of the Chamber of Colombian-Chinese Investment and Commerce.

From Mexico to Brazil, Chinese government and private projects have suffered extensive delays, been suspended or never even gotten off the ground. Corruption, cultural differences and bureaucracy in Latin America have halted momentum for many of them. China “realized that some of these projects…ended up in very unstable political destinations,” IMF economist Alejandro Werner said recently at the Council of Americas in New York. Werner has a point: China has dumped much of its cash into Brazil and Venezuela. Both are in deep recessions, and both have growing political instability. There are factions that want to impeach the current presidents, Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil.

China targeted Venezuela because it has the world’s largest oil reserves. China sees a long-term energy partner. Since 2007, China has loaned $65 billion to Venezuela alone, more than any other country in the region, according to the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington non-profit. That cash isn’t doing much. Its economy is “imploding,” says Werner. Falling oil prices have crushed Venezuela’s oil-dependent economy. Now China is trying to make sure its oil bet in Venezuela doesn’t go belly up. “They’re now giving loans to protect their previous loans,” says Boston University professor Kevin Gallagher, an expert on China-Latin America. “They’re so overexposed in Venezuela.”

Read more …

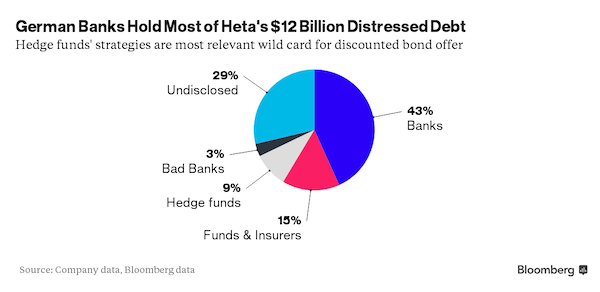

The HETA blow-up will happen at some point.

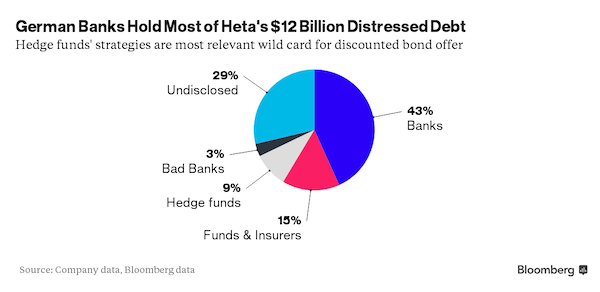

• Pimco’s $12 Billion Standoff Over Austria Bad Bank (BBG)

As the health of banks roils markets anew, the last financial crisis is still playing out in Austria, with Pacific Investment Management Co. on the hook. Pimco has teamed up with hedge funds and German banks to reject an €11 billion ($12 billion) offer of 75 cents on the euro for their holdings in what remains of Hypo Alpe-Adria-Bank International AG. A multiyear Argentina-style standoff looms a month before the government-set deadline. “We’re now in a period of psychological warfare,” Austrian central bank Governor Ewald Nowotny told reporters in Brussels last week. “In a purely economic view, everybody would be well advised to take the offer. I think it’s a fair offer, and it’s an adequate offer.”

The confrontation stems from Austria’s most painful bank failure of the 2008 financial crisis: Hypo Alpe was taken over by authorities after an ill-fated expansion in the former Yugoslavia. Once it sold the assets it could, the rest was turned into Heta Asset Resolution AG to be wound down. Austrian regulator FMA moved in March 2015 after an asset review revealed a larger hole in Heta’s finances. It then halted payments on the bonds. The settlement offer came from the southern province of Carinthia, which guaranteed Hypo Alpe’s debt when it was majority owner of the bank. It needs creditors representing two-thirds of the bonds to accept its offer by the March 11 deadline so that it can impose it on the rest. Currently just under half object; the group mounting the opposition says it accounts for about €5 billion, or 45%, of Heta’s debt.

“I was surprised a broad bondholder group rejected the offer so quickly since it didn’t seem too bad,” said Otto Dichtl at Stifel Financial Corp. “Some might have committed at least for the time being to stick together, but it doesn’t necessarily always make sense and the interests differ.” Pimco, which is owned by German insurer Allianz AG, is the only major buyer of the debt in the secondary market that has disclosed ownership, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. It took a bet on the distressed securities in 2014, based on regulatory filings.

Read more …

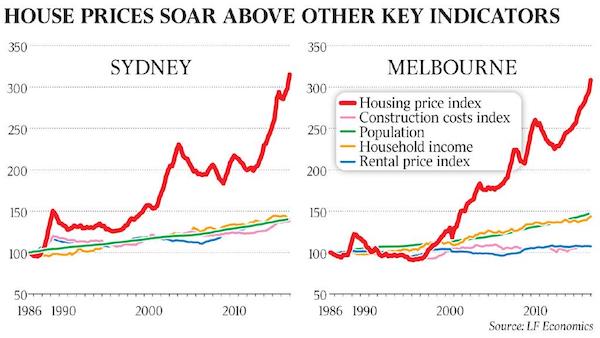

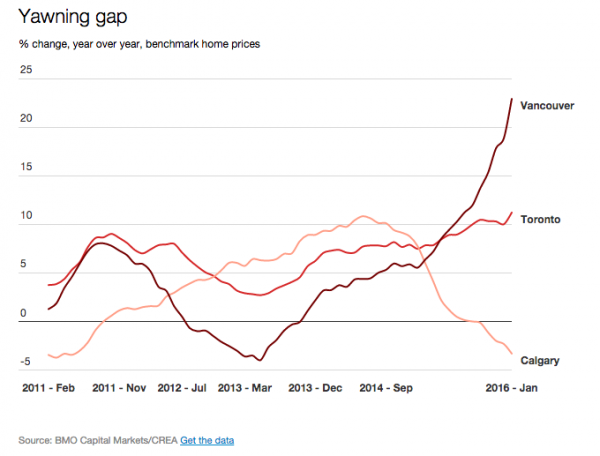

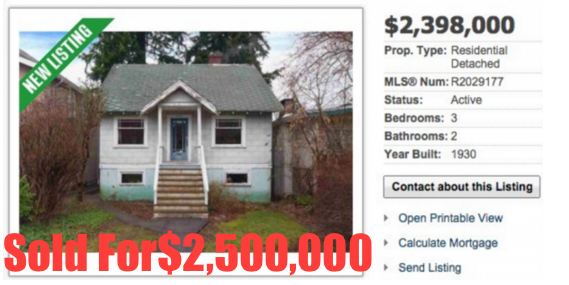

“Canadians know that this is a bubble, that these prices are unsustainable. They know that this bubble, like all bubbles, will eventually get pricked.”

• Things Are Coming Unglued for Canadian Investors (WS)

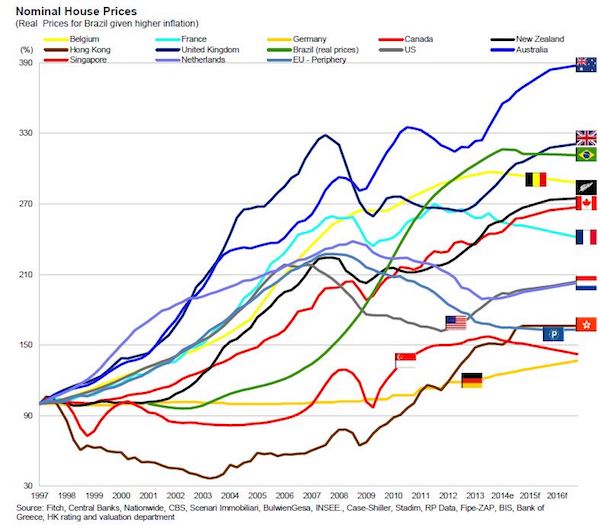

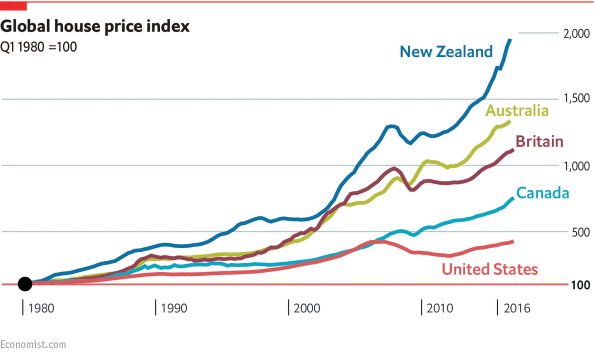

The oil price plunge is mauling Canada’s oil producers, particularly those active in the high-cost tar-sands. It’s tripping up the oil-patch economy, and contagion is spreading beyond the oil patch. The Canadian dollar has lost one third of its value against the US dollar since 2012. One of the most magnificent housing bubbles the world has ever seen appears to be peaking and is already deflating in some cities. And the Toronto stock index is down 25% since August 2014. No wonder Canadian investors are frazzled. And the semi-annual Manulife’s Investor Sentiment Index put a number on it: Canadians’ investment sentiment fell another 3 points from its beaten-down levels six months ago to 16, the lowest level since March 2009.

The index is a composite of investor perception about six asset classes – stocks, fixed income, cash, balanced funds, investment property, and investors’ own home. It has ranged from an all-time high of 34 in 2006, during the halcyon days just before the Financial Crisis when everything was still possible, to its all-time low of 5 at the end of 2008, at the depth of the Financial Crisis. By March 2009, it was at 11. Since then, it has hovered in the mid to high 20s. The survey, conducted in December, doesn’t yet include the impact of the sharp decline in oil prices to new cycle lows and the decline in stock prices since the holidays. At this point, the index hasn’t yet reached the level of desperation during the depths of the Financial Crisis, but it’s getting closer. The report:

Along with eroding investor sentiment is the feeling among Canadians that they are in a worse financial position than they were two years ago (26%). Canadians are increasingly viewing housing as a less attractive investment having dropped three points in the last year. The two largest drops were in British Columbia (13 point decrease since November 2014) and Ontario (decreased six points in the same time period).

Those two provinces are the epicenters of the Canadian housing bubble. According to the Teranet National Bank House Price Index, since the peak of the prior insane housing bubble in 2008, home prices in Vancouver have soared another 40% and in Toronto another 54%. Canadians know that this is a bubble, that these prices are unsustainable. They know that this bubble, like all bubbles, will eventually get pricked. It’s just a questions of when. In some cities, home prices are already declining. And investors, according to the report, are no longer blind to it.

Read more …

What can one do but laugh out loud?

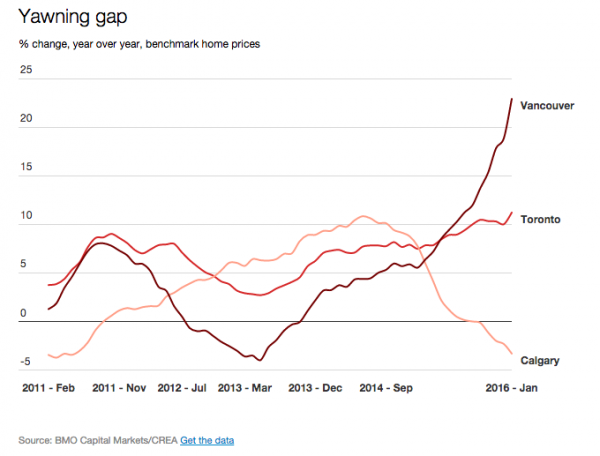

• Calgary Housing Market Collapses As “Three-Alarm Blaze” Burns In Vancouver (ZH)

New data out on Tuesday shows average property values on resold homes in the Greater Vancouver area rising by 30.9% in January while average prices in the Greater Toronto Area and in the abovementioned Waterloo rose 14.2% and 9% for the month, respectively. But oh what a difference a province makes. While the Canadian housing bubble is alive and well in Ontario and British Columbia, in the heart of Canada’s dying oil patch the picture isn’t pretty. We’ve documented the glut of vacant office space in downtown Calgary on a number of occasions. Calgary is of course in Alberta, where collapsing crude has driven WCS down to just CAD1 above marginal operating costs. That’s led employers to cut jobs. In fact, last year was the worst year for provincial job losses since 1982.

This has had a profound effect on Calgary and on Tuesday we learn that it isn’t just office space that’s sitting unoccupied. According to data from Altus Group sales of condos in the city fell a whopping 38% from 3,000 units to 4,805 units in 2015, marking the largest y/y drop since 2008. “The drop-off doesn’t bode well for 2016,” Bloomberg notes. “Calgary, the biggest city in the oil-producing province of Alberta, ended 2015 with one of the highest inventories of unsold condos, at 3,356 suites in the fourth quarter, according to Altus.” If you want to understand all of the above you need only look at the following chart which contrasts home prices in Calgary with those in Vancouver and Toronto:

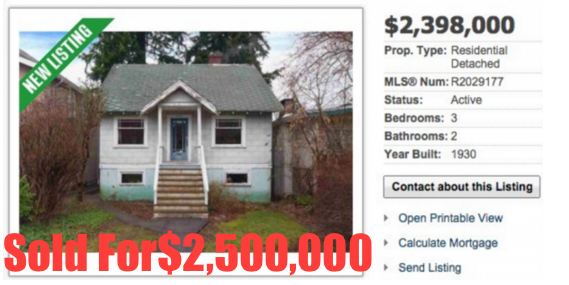

Clearly, one of those things isn’t like the others. “While we continue to believe that things just can’t any hotter, markets in B.C. and Ontario continue to prove us wrong,” TD economist Diana Petramala said. “[For Toronto and Vancouver], every month of double-digit home price growth raises the risk of a deeper home price correction down the road.” “Hot doesn’t quite describe Vancouver’s three-alarm fire of a housing market,” Bank of Montreal chief economist Doug Porter remarked. So while you can’t give condos and office space away in Calgary, you for all intents and purposes have to be a millionaire to afford to live in British Columbia and especially in Vancouver which, judging by the parabolic chart shown above, is one of the most desirable locales on the face of the planet. We close by noting that the Canadian real estate “bargain” we profiled three weeks ago has indeed sold – for $102,000 more than the original asking price…

Read more …

“Donald the T-bomber.”

• What Are We Smelling? (Dmitry Orlov)

On the Democratic side, we have Hillary the Giant Flying Lizard, but she seems rather impaired by just about everything she has ever done, some of which was so illegal that it will be hard to keep her from being indicted prior to the election. She seems only popular in the sense that, if she were stuffed and mounted and put on display, lots of folks would pay good money to take turns throwing things at her. And then we have Bernie, the pied piper for the “I can’t believe I can’t change things by voting” crowd. He seems to be doing a good job of it—as if that mattered.

On the Republican side we have Donald and the Seven Dwarfs. I previously wrote that I consider Donald to be a mannequin worthy of being installed as a figurehead at the to-be-rebranded Trump White House and Casino (it is beneath my dignity to mention any of the Dwarfs by name) but Donald has a problem: he sometime tells the truth. In the most recent debate with the Dwarfs he said that Bush lied in order to justify the invasion of Iraq. Candidates must lie—lie like, you know, like they are running for office. And the problem with telling the truth is that it becomes hard to stop. What bit of truthiness is he going to deliver next? That 9/11 was an inside job? That Osama bin Laden worked for the CIA, and that his death was faked? That the Boston Marathon bombing was staged, and the two Chechen lads were patsies?

That the US military is a complete waste of money and cannot win? That the financial and economic collapse of the US is now unavoidable? Even if he can stop himself from letting any more truthiness leak out, the trust has been broken: now that he’s dropped the T-bomb, how can he be relied upon to lie like he’s supposed to? And so we may be treated to quite a spectacle: the Flying Lizard, slouching toward a federal penitentiary, squaring off against the Donald the T-bomber. That would be fun to watch. Or maybe the Lizard will implode on impact with the voting booth and then we’ll have Bernie vs. the T-bomber. Being a batty old bugger, and not wanting to be outdone, he might drop some T-bombs of his own. That would be fun to watch too.

Not that any of this matters, of course, because the country’s trajectory is all set. And no matter who gets elected—Bernie or Donald—on their first day at the White House they will be shown a short video which will explain to them what exactly they need to do to avoid being assassinated. But I won’t be around to see any of that. I’ve seen enough. This summer I am sailing off: out Port Royal Sound, then across the Gulf Stream and over to the Abacos, then a series of pleasant day-sails down the Bahamas chain with breaks for fishing, snorkeling and partying with other sailors (I know, life is so hard!), then through the Windward Passage, a stop at Port Antonio in Jamaica, and then onward across the Caribbean to an undisclosed location. Please let me know if you want to crew. I guarantee that there will be absolutely no election coverage aboard the boat.

Read more …

Europe must side with Greece, not Turkey. Big mistake.

• Not a game (Papachelas)

Greece’s relations with Turkey require deft handling and caution. Responsibility for this, of course, lies with Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras. One does not need to be a geostrategic analyst to see that things aren’t going at all well at the moment. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is out of control. He is not willing to listen to anyone and has thrown himself into risky gambits. Meanwhile, the US under President Barack Obama has essentially been absent from the region and is seemingly reluctant to play its traditional role. Even if Washington did want to step in, I’m not sure that Erdogan would take a call from the US leader. The rest of Europe is treating Erdogan with a mix of panic and awe. Deep down European leaders know that they don’t have any really effective ways of putting pressure on Turkey. Erdogan knows this and is acting accordingly.

That said, our fellow Europeans are to some extent ignorant of Greek-Turkish disputes, and this carries some risk. They have no in-depth knowledge of the issues dividing the two Aegean neighbors and their response is along the following lines: “Well, if you have differences, why don’t you just sit around a table and talk them through?” Indeed, judging from the manner in which European leaders have dealt with the ongoing refugee and migrant crisis, I don’t even want to know how they would deal with a Greek-Turkish crisis. All that is happening as Greece is going through one of its worst periods. The volatile regional environment combined with Greece’s image of a powerless state inspires little optimism for the future. Some observers suggest that Greece has some strong cards up its sleeve, a reference to Israel and Russia.

Perhaps they know something that remains elusive to us mortals. However, if one thing is certain, it is that changing a country’s foreign policy dogma and interpreting international alliances or the balance of power must come with a good deal of caution and restraint. This not a game. Every time Greek leaders have made a mistake, the country has paid a heavy price. Every time they have done a good job of figuring out who our allies are and gauging outside developments, the country has moved forward. These are crucial times for the broader region. It is crucial that we play our cards right and avoid any damage to our national sovereignty. Fortunately Greece can depend on some people who have in-depth knowledge of the issues and who combine determination with wisdom.

I once asked Tsipras, while he was still in the opposition, who he would call first call in case of an incident in the Aegean. “Surely that would be Erdogan,” he said. I was not sure what to make of his answer back then and I would be interested to know what his response would be today.

Read more …